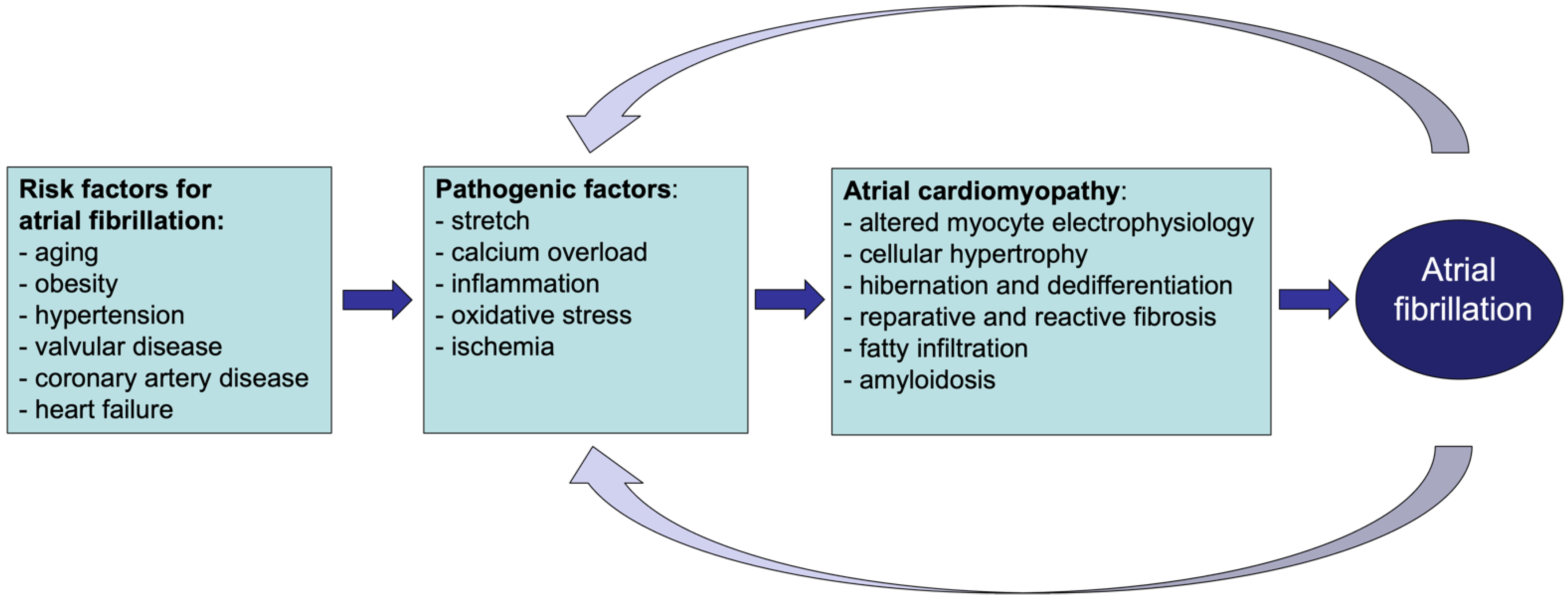

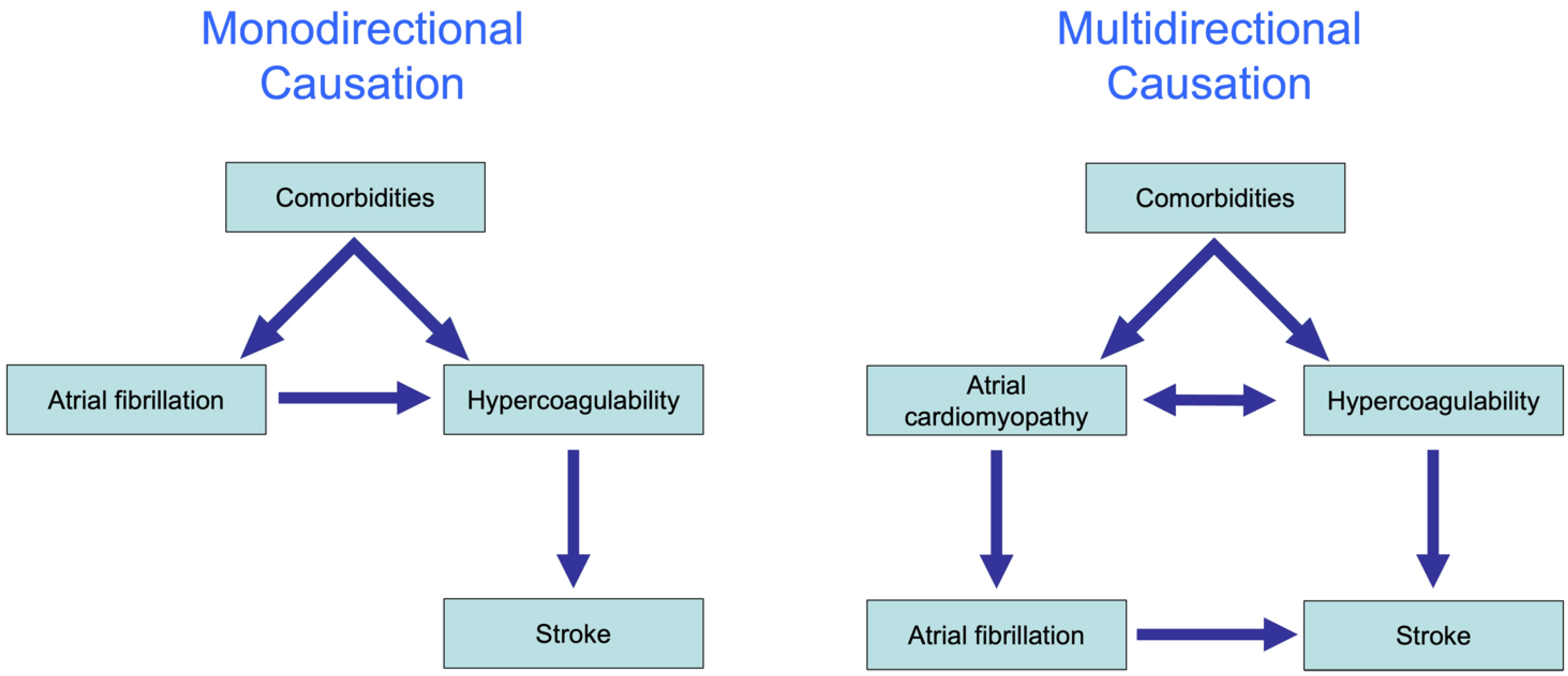

Heart disease, as well as systemic metabolic alterations, can leave a ‘fingerprint’ of structural and functional changes in the atrial myocardium, leading to the onset of atrial cardiomyopathy. As demonstrated in various animal models, some of these changes, such as fibrosis, cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and fatty infiltration, can increase vulnerability to atrial fibrillation (AF), the most relevant manifestation of atrial cardiomyopathy in clinical practice. Atrial cardiomyopathy accompanying AF is associated with thromboembolic events, such as stroke. The interaction between AF and stroke appears to be far more complicated than initially believed. AF and stroke share many risk factors whose underlying pathological processes can reinforce the development and progression of both cardiovascular conditions.

- atrial cardiomyopathy

- atrial fibrillation

- thrombogenesis

1. Atrial Cardiomyopathy and Atrial Fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained tachyarrhythmia in clinical practice. The prevalence of AF rises steeply with age [1]. It has long been recognized that the risk for AF is increased by underlying structural heart disease, including coronary artery disease, prior myocardial infarction, heart failure and valvular disease [1]. This led to the distinction between ‘AF with preexisting structural heart disease’ and ‘lone AF’, i.e., AF occurring in the absence of structural heart disease. However, many other non-cardiac disease factors also increase the likelihood of AF, e.g., obesity, sleep apnea, and hyperthyroidism, in the absence of clinically detectable changes in the cardiac structure or function [1,2][1][2]. For example, diabetes mellitus has been associated with an increased risk of developing AF. The mechanisms by which this metabolic disorder would lead to AF are still under debate. Growing evidence suggests the involvement of diabetes-related oxidative stress and inflammatory state [3]. Moreover, glucose and insulin disturbances are also associated with pathological changes in the heart, as suggested by the increase in the left ventricular mass accompanying the worsening of glucose intolerance [4].

2. Atrial Cardiomyopathy and Thrombogenesis

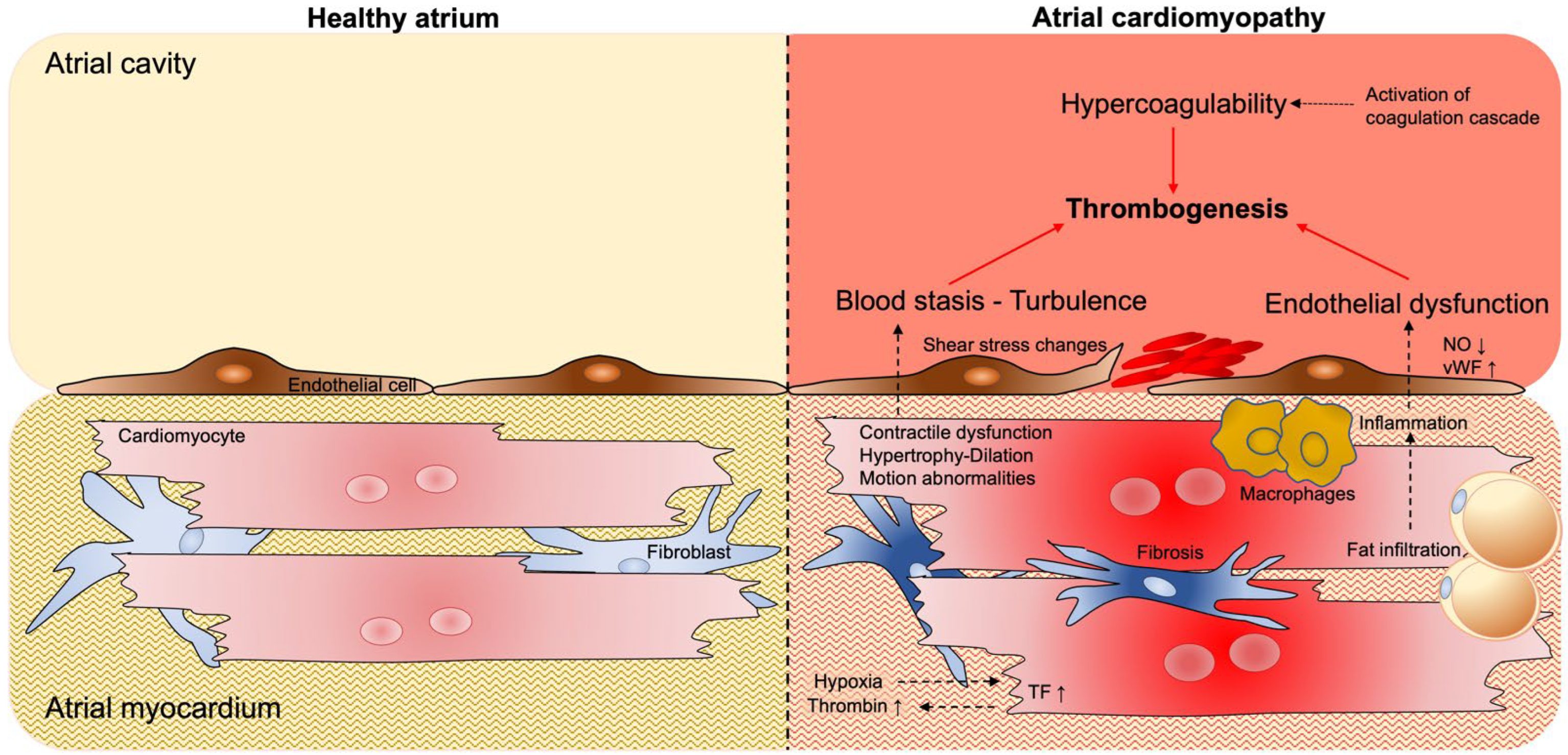

2.1. Blood Stasis and Endothelial Dysfunction

2.2. Pro-Thrombotic Interstitial Changes

2.3. Hypercoagulability

Another mechanism that contributes to thrombogenesis in AF and in other atrial cardiomyopathies consists of alterations in blood constituents which confer a hypercoagulable state [93][41]. Hypercoagulability in AF patients is often reflected by increased systemic platelet activation, elevated concentrations of pro-thrombotic indices (e.g., prothrombin fragments 1 + 2 and thrombin–antithrombin complex) and altered fibrinolytic activity [61][14]. Interestingly, the activation of the coagulation system in AF may not be homogeneous throughout the body. Some studies have shown that platelet activation and thrombin generation markers were elevated in the atria of patients within minutes after AF induction, or as a consequence of rapid atrial pacing (RAP) in animal models, compared to peripheral circulation [94,95][42][43]. These data highlight the effect of rhythm and rate on atrial pro-thrombotic mechanisms (e.g., local endocardial dysfunction/damage), which may promote a local pro-thrombotic environment. Nevertheless, it is still not fully clarified whether “lone AF” (AF in the absence of apparent comorbidities) is sufficient to cause a pro-thrombotic state, or whether the presence of other underlying comorbidities and risk factors is required.3. Activation of Coagulation Supports Atrial Cardiomyopathy

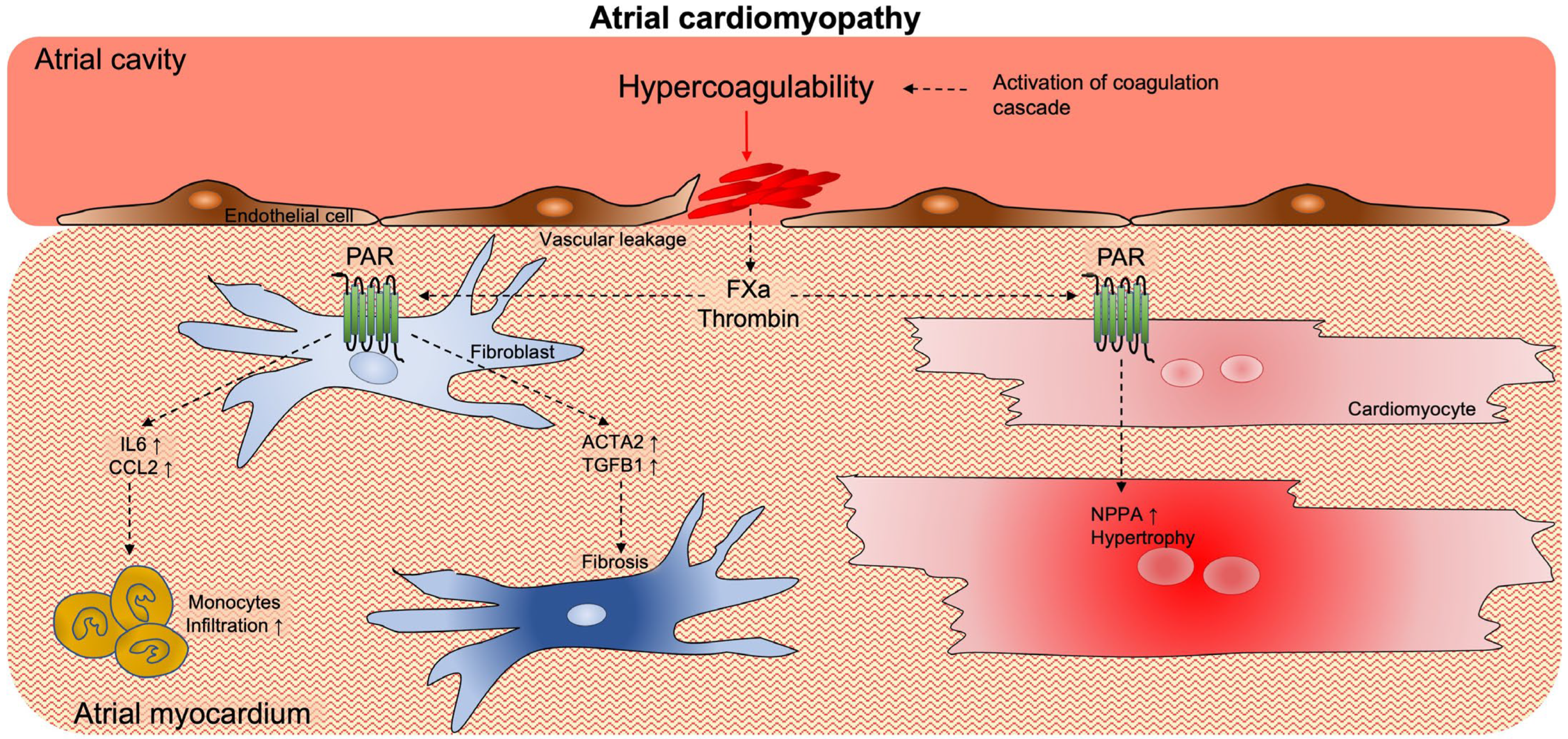

Activated coagulation factors, such as thrombin and FXa, can modulate physiological and pathological processes, such as inflammation and fibrosis, which may contribute to atrial cardiomyopathy (Figure 3) [102,103][44][45]. These extravascular (non-hemostatic) functions impact different cell types (e.g., endothelial cells, cardiomyocytes and cardiac fibroblasts) via the activation of protease-activated receptors (PAR) [104][46]. The PAR family consists of four isoforms (PAR-1 to −4). Activated coagulation proteases, such as thrombin and FXa, cleave PAR at the N-terminus and generate an exposed N-tethered ligand that self-activates the receptor [105][47].

4. The Complex Association of AF and Thrombogenesis (Stroke)

References

- Hindricks, G.; Potpara, T.; Dagres, N.; Arbelo, E.; Bax, J.J.; Blomstrom-Lundqvist, C.; Boriani, G.; Castella, M.; Dan, G.A.; Dilaveris, P.E.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 373–498.

- Fabritz, L.; Guasch, E.; Antoniades, C.; Bardinet, I.; Benninger, G.; Betts, T.R.; Brand, E.; Breithardt, G.; Bucklar-Suchankova, G.; Camm, A.J.; et al. Expert consensus document: Defining the major health modifiers causing atrial fibrillation: A roadmap to underpin personalized prevention and treatment. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2016, 13, 230–237.

- Karam, B.S.; Chavez-Moreno, A.; Koh, W.; Akar, J.G.; Akar, F.G. Oxidative stress and inflammation as central mediators of atrial fibrillation in obesity and diabetes. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2017, 16, 120.

- Rutter, M.K.; Parise, H.; Benjamin, E.J.; Levy, D.; Larson, M.G.; Meigs, J.B.; Nesto, R.W.; Wilson, P.W.; Vasan, R.S. Impact of glucose intolerance and insulin resistance on cardiac structure and function: Sex-related differences in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2003, 107, 448–454.

- Goette, A.; Kalman, J.M.; Aguinaga, L.; Akar, J.; Cabrera, J.A.; Chen, S.A.; Chugh, S.S.; Corradi, D.; D’Avila, A.; Dobrev, D.; et al. EHRA/HRS/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus on atrial cardiomyopathies: Definition, characterization, and clinical implication. Europace 2016, 18, 1455–1490.

- Schotten, U.; Verheule, S.; Kirchhof, P.; Goette, A. Pathophysiological mechanisms of atrial fibrillation: A translational appraisal. Physiol. Rev. 2011, 91, 265–325.

- Hatem, S.N.; Sanders, P. Epicardial adipose tissue and atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2014, 102, 205–213.

- Verheule, S.; Schotten, U. Electrophysiological Consequences of Cardiac Fibrosis. Cells 2021, 10, 3220.

- Ausma, J.; Dispersyn, G.D.; Duimel, H.; Thone, F.; Ver Donck, L.; Allessie, M.A.; Borgers, M. Changes in ultrastructural calcium distribution in goat atria during atrial fibrillation. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2000, 32, 355–364.

- van Bragt, K.A.; Nasrallah, H.M.; Kuiper, M.; Luiken, J.J.; Schotten, U.; Verheule, S. Atrial supply-demand balance in healthy adult pigs: Coronary blood flow, oxygen extraction, and lactate production during acute atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2014, 101, 9–19.

- Eckstein, J.; Verheule, S.; de Groot, N.M.; Allessie, M.; Schotten, U. Mechanisms of perpetuation of atrial fibrillation in chronically dilated atria. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2008, 97, 435–451.

- Dudley, S.C., Jr.; Hoch, N.E.; McCann, L.A.; Honeycutt, C.; Diamandopoulos, L.; Fukai, T.; Harrison, D.G.; Dikalov, S.I.; Langberg, J. Atrial fibrillation increases production of superoxide by the left atrium and left atrial appendage: Role of the NADPH and xanthine oxidases. Circulation 2005, 112, 1266–1273.

- Lip, G.Y.; Nieuwlaat, R.; Pisters, R.; Lane, D.A.; Crijns, H.J. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: The euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest 2010, 137, 263–272.

- Watson, T.; Shantsila, E.; Lip, G.Y. Mechanisms of thrombogenesis in atrial fibrillation: Virchow’s triad revisited. Lancet 2009, 373, 155–166.

- Lip, G.Y. Does atrial fibrillation confer a hypercoagulable state? Lancet 1995, 346, 1313–1314.

- Schotten, U.; Duytschaever, M.; Ausma, J.; Eijsbouts, S.; Neuberger, H.R.; Allessie, M. Electrical and contractile remodeling during the first days of atrial fibrillation go hand in hand. Circulation 2003, 107, 1433–1439.

- Manning, W.J.; Silverman, D.I.; Katz, S.E.; Riley, M.F.; Come, P.C.; Doherty, R.M.; Munson, J.T.; Douglas, P.S. Impaired left atrial mechanical function after cardioversion: Relation to the duration of atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1994, 23, 1535–1540.

- Vincenti, A.; Genovesi, S.; Sonaglioni, A.; Binda, G.; Rigamonti, E.; Lombardo, M.; Anza, C. Mechanical atrial recovery after cardioversion in persistent atrial fibrillation evaluated by bidimensional speckle tracking echocardiography. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 20, 745–751.

- Fatkin, D.; Kuchar, D.L.; Thorburn, C.W.; Feneley, M.P. Transesophageal echocardiography before and during direct current cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: Evidence for “atrial stunning” as a mechanism of thromboembolic complications. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1994, 23, 307–316.

- Airaksinen, K.E.; Gronberg, T.; Nuotio, I.; Nikkinen, M.; Ylitalo, A.; Biancari, F.; Hartikainen, J.E. Thromboembolic complications after cardioversion of acute atrial fibrillation: The FinCV (Finnish CardioVersion) study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, 1187–1192.

- Spartera, M.; Stracquadanio, A.; Pessoa-Amorim, G.; Von Ende, A.; Fletcher, A.; Manley, P.; Ferreira, V.M.; Hess, A.T.; Hopewell, J.C.; Neubauer, S.; et al. The impact of atrial fibrillation and stroke risk factors on left atrial blood flow characteristics. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 23, 115–123.

- Uematsu, M.; Ohara, Y.; Navas, J.P.; Nishida, K.; Murphy, T.J.; Alexander, R.W.; Nerem, R.M.; Harrison, D.G. Regulation of endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase mRNA expression by shear stress. Am. J. Physiol. 1995, 269, C1371–C1378.

- Neuberger, H.-R.; Schotten, U.; Verheule, S.; Eijsbouts, S.; Blaauw, Y.; van Hunnik, A.; Allessie, M.A. Development of a substrate of atrial fibrillation during chronic atrioventricular block in the goat. Circulation 2005, 111, 30–37.

- Liu, L.; Yun, F.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, D.; Peng, W.; Li, S.; Xiu, C.; et al. Atrial sympathetic remodeling in experimental hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism rats. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 187, 148–150.

- Greiser, M.; Neuberger, H.R.; Harks, E.; El-Armouche, A.; Boknik, P.; de Haan, S.; Verheyen, F.; Verheule, S.; Schmitz, W.; Ravens, U.; et al. Distinct contractile and molecular differences between two goat models of atrial dysfunction: AV block-induced atrial dilatation and atrial fibrillation. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2009, 46, 385–394.

- Benjamin, E.J.; D’Agostino, R.B.; Belanger, A.J.; Wolf, P.A.; Levy, D. Left atrial size and the risk of stroke and death. The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 1995, 92, 835–841.

- Ammash, N.; Konik, E.A.; McBane, R.D.; Chen, D.; Tange, J.I.; Grill, D.E.; Herges, R.M.; McLeod, T.G.; Friedman, P.A.; Wysokinski, W.E. Left atrial blood stasis and Von Willebrand factor-ADAMTS13 homeostasis in atrial fibrillation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, 2760–2766.

- Fukuchi, M.; Watanabe, J.; Kumagai, K.; Katori, Y.; Baba, S.; Fukuda, K.; Yagi, T.; Iguchi, A.; Yokoyama, H.; Miura, M.; et al. Increased von Willebrand factor in the endocardium as a local predisposing factor for thrombogenesis in overloaded human atrial appendage. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001, 37, 1436–1442.

- Lip, G.Y.; Blann, A. von Willebrand factor: A marker of endothelial dysfunction in vascular disorders? Cardiovasc. Res. 1997, 34, 255–265.

- Wysokinski, W.E.; Melduni, R.M.; Ammash, N.M.; Vlazny, D.T.; Konik, E.; Saadiq, R.A.; Gosk-Bierska, I.; Slusser, J.; Grill, D.; McBane, R.D. Von Willebrand Factor and ADAMTS13 as Predictors of Adverse Outcomes in Patients with Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation. CJC Open 2021, 3, 318–326.

- Nso, N.; Bookani, K.R.; Metzl, M.; Radparvar, F. Role of inflammation in atrial fibrillation: A comprehensive review of current knowledge. J. Arrhythm. 2021, 37, 1–10.

- Korantzopoulos, P.; Letsas, K.P.; Tse, G.; Fragakis, N.; Goudis, C.A.; Liu, T. Inflammation and atrial fibrillation: A comprehensive review. J. Arrhythm. 2018, 34, 394–401.

- Yau, J.W.; Teoh, H.; Verma, S. Endothelial cell control of thrombosis. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2015, 15, 130.

- Nakamura, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Fukushima-Kusano, K.; Ohta, K.; Matsubara, H.; Hamuro, T.; Yutani, C.; Ohe, T. Tissue factor expression in atrial endothelia associated with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: Possible involvement in intracardiac thrombogenesis. Thromb. Res. 2003, 111, 137–142.

- Nightingale, T.; Cutler, D. The secretion of von Willebrand factor from endothelial cells; an increasingly complicated story. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2013, 11 (Suppl. 1), 192–201.

- D’Alessandro, E.; Posma, J.J.N.; Spronk, H.M.H.; Ten Cate, H. Tissue factor (:Factor VIIa) in the heart and vasculature: More than an envelope. Thromb. Res. 2018, 168, 130–137.

- Zhu, W.; Zhang, H.; Guo, L.; Hong, K. Relationship between epicardial adipose tissue volume and atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Herz 2016, 41, 421–427.

- Kocyigit, D.; Gurses, K.M.; Yalcin, M.U.; Turk, G.; Evranos, B.; Yorgun, H.; Sahiner, M.L.; Kaya, E.B.; Hazirolan, T.; Tokgozoglu, L.; et al. Periatrial epicardial adipose tissue thickness is an independent predictor of atrial fibrillation recurrence after cryoballoon-based pulmonary vein isolation. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2015, 9, 295–302.

- Antonopoulos, A.S.; Margaritis, M.; Verheule, S.; Recalde, A.; Sanna, F.; Herdman, L.; Psarros, C.; Nasrallah, H.; Coutinho, P.; Akoumianakis, I.; et al. Mutual Regulation of Epicardial Adipose Tissue and Myocardial Redox State by PPAR-gamma/Adiponectin Signalling. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 842–855.

- Mahajan, R.; Nelson, A.; Pathak, R.K.; Middeldorp, M.E.; Wong, C.X.; Twomey, D.J.; Carbone, A.; Teo, K.; Agbaedeng, T.; Linz, D.; et al. Electroanatomical Remodeling of the Atria in Obesity: Impact of Adjacent Epicardial Fat. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2018, 4, 1529–1540.

- Choudhury, A.; Lip, G.Y. Atrial fibrillation and the hypercoagulable state: From basic science to clinical practice. Pathophysiol. Haemost. Thromb. 2003, 33, 282–289.

- Lim, H.S.; Willoughby, S.R.; Schultz, C.; Gan, C.; Alasady, M.; Lau, D.H.; Leong, D.P.; Brooks, A.G.; Young, G.D.; Kistler, P.M.; et al. Effect of atrial fibrillation on atrial thrombogenesis in humans: Impact of rate and rhythm. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 61, 852–860.

- Bartus, K.; Litwinowicz, R.; Natorska, J.; Zabczyk, M.; Undas, A.; Kapelak, B.; Lakkireddy, D.; Lee, R.J. Coagulation factors and fibrinolytic activity in the left atrial appendage and other heart chambers in patients with atrial fibrillation: Is there a local intracardiac prothrombotic state? (HEART-CLOT study). Int. J. Cardiol. 2020, 301, 103–107.

- Spronk, H.M.; de Jong, A.M.; Crijns, H.J.; Schotten, U.; Van Gelder, I.C.; Ten Cate, H. Pleiotropic effects of factor Xa and thrombin: What to expect from novel anticoagulants. Cardiovasc. Res. 2014, 101, 344–351.

- Ten Cate, H.; Guzik, T.J.; Eikelboom, J.; Spronk, H.M.H. Pleiotropic actions of factor Xa inhibition in cardiovascular prevention: Mechanistic insights and implications for anti-thrombotic treatment. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 117, 2030–2044.

- Rothmeier, A.S.; Ruf, W. Protease-activated receptor 2 signaling in inflammation. Semin. Immunopathol. 2012, 34, 133–149.

- Gieseler, F.; Ungefroren, H.; Settmacher, U.; Hollenberg, M.D.; Kaufmann, R. Proteinase-activated receptors (PARs)—Focus on receptor-receptor-interactions and their physiological and pathophysiological impact. Cell Commun. Signal. 2013, 11, 86.

- Spronk, H.M.; De Jong, A.M.; Verheule, S.; De Boer, H.C.; Maass, A.H.; Lau, D.H.; Rienstra, M.; van Hunnik, A.; Kuiper, M.; Lumeij, S.; et al. Hypercoagulability causes atrial fibrosis and promotes atrial fibrillation. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 38–50.

- Ausma, J.; Litjens, N.; Lenders, M.H.; Duimel, H.; Mast, F.; Wouters, L.; Ramaekers, F.; Allessie, M.; Borgers, M. Time course of atrial fibrillation-induced cellular structural remodeling in atria of the goat. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2001, 33, 2083–2094.

- Guo, X.; Kolpakov, M.A.; Hooshdaran, B.; Schappell, W.; Wang, T.; Eguchi, S.; Elliott, K.J.; Tilley, D.G.; Rao, A.K.; Andrade-Gordon, P.; et al. Cardiac Expression of Factor X Mediates Cardiac Hypertrophy and Fibrosis in Pressure Overload. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2020, 5, 69–83.

- Matsuura, T.; Soeki, T.; Fukuda, D.; Uematsu, E.; Tobiume, T.; Hara, T.; Kusunose, K.; Ise, T.; Yamaguchi, K.; Yagi, S.; et al. Activated Factor X Signaling Pathway via Protease-Activated Receptor 2 Is a Novel Therapeutic Target for Preventing Atrial Fibrillation. Circ. J. 2021, 85, 1383–1391.

- Kondo, H.; Abe, I.; Fukui, A.; Saito, S.; Miyoshi, M.; Aoki, K.; Shinohara, T.; Teshima, Y.; Yufu, K.; Takahashi, N. Possible role of rivaroxaban in attenuating pressure-overload-induced atrial fibrosis and fibrillation. J. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 310–319.

- D’Alessandro, E.; Scaf, B.; Munts, C.; van Hunnik, A.; Trevelyan, C.J.; Verheule, S.; Spronk, H.M.H.; Turner, N.A.; Ten Cate, H.; Schotten, U.; et al. Coagulation Factor Xa Induces Proinflammatory Responses in Cardiac Fibroblasts via Activation of Protease-Activated Receptor-1. Cells 2021, 10, 2958.