Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) is defined as a bacterial infection of the ascitic fluid without a surgically treatable intra-abdominal infection source. SBP is a common, severe complication in cirrhosis patients with ascites, and if left untreated, in-hospital mortality may exceed 90%. However, the incidence of SBP has been lowered to approx. 20% through early diagnosis and antibiotic therapy. There are three types of SBP. Bacterial translocation from the gastrointestinal tract is the most common source of SBP. Distinguishing SBP from secondary bacterial peritonitis is essential because the conditions require different therapeutic strategies. The standard treatment for SBP is prompt broad-spectrum antibiotic administration and should be tailored according to community-acquired SBP, healthcare-associated or nosocomial SBP infections, and local resistance profile. Albumin supplementation, especially in patients with renal impairment, is also beneficial. Selective intestinal decontamination is associated with a reduced risk of bacterial infection and mortality in the high-risk group.

- spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

- liver cirrhosis

- culture-negative neutrophilic ascites

- monomicrobial non-neutrocytic bacterascites

- bacterial translocation

- ascites fluid

- Gram-negative bacilli

- Gram-positive cocci

- antibiotic prophylaxis

1. Introduction

| Ascites Fluid | Classic SBP | CNNA | 1 | MNB | 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMN count (cells/mm | 3 | ) | ≥250 | ≥250 | <250 |

| Ascites culture | positive | negative | positive |

2. Pathogenesis

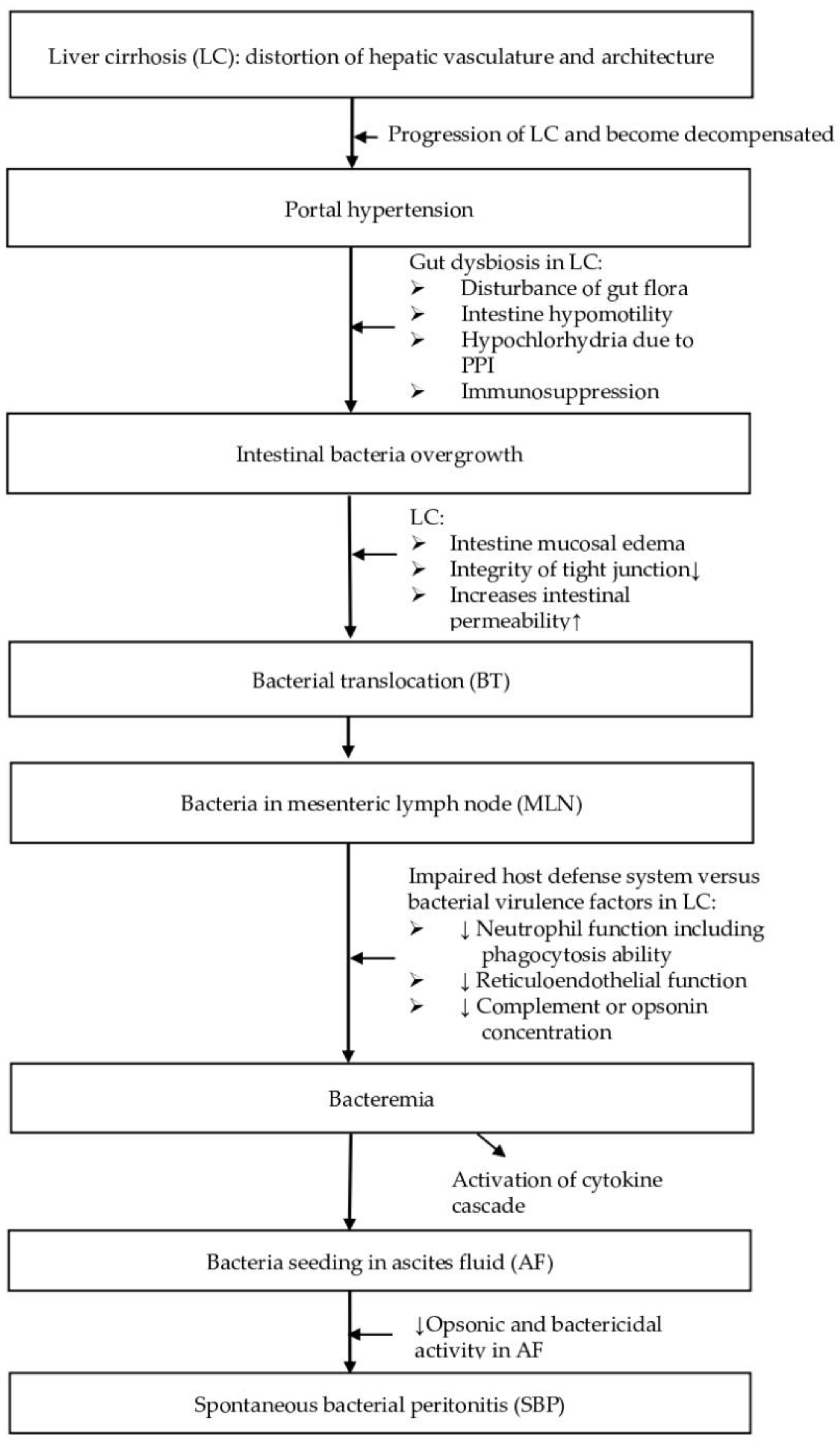

Mechanisms that may be involved in the pathogenesis of SBP are shown in Figure 1.

2.1. Gut Dysbiosis

One of the early stages in the development of SBP is the disturbance of gut flora leading to bacterial overgrowth and extra-intestinal dissemination of gut microorganisms [21][11]. Edema of the small intestine and ascending colon alters tight junction integrity and increases intestinal permeability, thus predisposing the patient to bacterial overgrowth in the presence of cirrhosis [21][11]. Altered small intestinal motility, presence of hypochlorhydria due to the use of proton pump inhibitors, and immunosuppression therapies commonly used during cirrhosis may also contribute to bacterial overgrowth.2.2. Bacterial Translocation

Another important step following bacterial overgrowth is the translocation of enteric bacteria to extraintestinal sites, such as the mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN), which drain lymph from the gut [21][11]. Bacterial translocation (BT) has been defined as culture-positive MLN [22][12] and is culture-negative in healthy experimental animals without cirrhosis [22][12] but culture pathogenic bacteria in 78.1% of animals with cirrhosis and ascites [21][11]. The fact that SBP is monomicrobial implies that there are “filters” between polymicrobial intestinal sources and the ascitic fluid [21][11]. The first filter is the gut mucosa itself, and the second filter is the MLN [21][11]. If these MLN fail to sequester and destroy the bacteria, the pathogens can move from the mesenteric lymphatic system to systemic circulation and then percolate through the liver and extravasate across Glisson’s capsule to enter the ascitic fluid [23][13].2.3. Impaired Host Defense System

Conversely, the host defense system also plays an important role in SBP pathogenesis. Once a microorganism enters the ascitic fluid, a battle ensues between the invading bacteria and the host’s immune system. Peritoneal macrophages are the first line of defense in the peritoneal cavity [26,27][14][15]. If these phagocytes fail to eradicate the invading microorganism, the complement system is activated, and cytokines are released [28][16]. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) then enter the peritoneum to eliminate the foreign bacteria. However, cirrhotic patients are known to have impairment in neutrophil and reticuloendothelial function [29,30][17][18]. In addition, many cirrhotic patients with ascites have a complement or opsonin deficiency [31][19]. The opsonic activity of ascitic fluid parallels the ascitic fluid total protein concentration [32][20]. Since opsonins are required by phagocytic cells to eliminate the offending microorganisms, cirrhotic patients with an ascitic fluid protein concentration of less than or equal to (≦) 1 g/dL are 10-times more likely to develop SBP during hospitalization than those with a protein concentration greater than (>) 1 g/dL [31][19].3. Bacteriology

Bacterial translocation (BT) from the GI tract is the most common source of SBP. However, especially in nosocomial SBP, other sources, such as transient bacteremia due to invasive procedures, can also lead to SBP [33][21]. The bacteriology of SBP can be classified into Gram-negative bacilli, Gram-positive cocci, multidrug-resistant microorganisms, and anaerobes by bacterial spectrum, and classified into community acquired (CA), healthcare-associated (HCA), and nosocomial (hospital-acquired) infections by facilities. Two thirds (66.7%) of SBP cases are caused by Gram-negative bacilli (GNB) from BT, almost exclusively Enterobacteriaceae, and occur independently from the site of acquisition [3,19][3][22]. Escherichia coli (E. coli) is the most frequently isolated pathogen (46–70%) [3[3][23],34], followed by Streptococcus pneumoniae (18–19%) and Klebsiella (9–13%) [19,34][22][23]. On the other hand, Gram-positive organisms accounted for less than one third (33.3%) of SBP and were predominated by Streptococcus (60%) and Staphylococcus aureus (40%) [19,35][22][24]. The emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) microorganisms, such as extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing GNB and enterococci [40][25], fluroquinolone-resistant (QR) GNB [41][26], cefoxitin/methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) [11][27], vancomycin-resistant enterococcus (VRE), and other resistant microorganisms [40][25] have altered prior conceptions toward SBP bacteriology and treatment [42][28]. Although gut floras are responsible for the majority of SBP cases, anaerobes appear to be rare, presumably due to the high oxygen content of the intestinal wall and AF, as well as because of the relative inability of anaerobes to translocate across the intestinal mucosa [46,47][29][30].4. Diagnosis

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) should be suspected in patients with cirrhosis who develop signs or symptoms, such as fever (69%), abdominal pain (59%), altered mental status (54%), abdominal tenderness (49%), diarrhea (32%), ileus (30%), hypotension/shock (21%), or hypothermia (17%) [46][29]. However, 10% of cases show no signs or symptoms, partly because a large volume of ascites prevents contact of the visceral and parietal peritoneal surfaces to elicit the spinal reflux that cause abdominal rigidity [46][29].

A diagnostic paracentesis should be performed in all patients with cirrhosis and ascites who require emergency room care or hospitalization, who demonstrate or report signs/symptoms mentioned above in the clinical presentations, or who present gastrointestinal bleeding, in order to confirm evidence of SBP [49][31]. However, low clinical suspicion for SBP does not preclude the necessity for paracentesis, since 10% of cases have no signs or symptoms [46][29].

Ascitic fluid tests should include cell count with a differential, Gram stain, culture, total protein, and albumin to calculate the serum-ascites albumin gradient (SAAG), if not already known [11][27]. When the diagnosis of cirrhosis is not definite, an ascites SAAG greater than or equal to (≧) 1.1 g/dl is ascribed to portal hypertension with approximately 97% accuracy [49][31]. Total ascitic fluid protein concentration should be measured to assess the risk of SBP since patients suffering from ascites with a total protein concentration lower than (<) 1.5 g/dL are at increased risk of SBP [7].

A diagnosis of (1) classic SBP is made if PMN count in the ascitic fluid is ≥250 cells/mm3, culture results are positive, and secondary causes of peritonitis are excluded [7,49][7][31]. A potential source of error in PMN count is hemorrhage into the ascitic fluid, such as with traumatic paracentesis, which can cause both red and white blood cells to enter the ascites. A corrected PMN count should be calculated if there are bloody ascites by subtracting one PMN from the absolute PMN count for every 250 red cells/mm3 [55][32]. Distinguishing SBP from secondary bacterial peritonitis is essential because the conditions require different therapeutic strategies. Mortality from SBP can be as high as 85% if a patient undergoes an unnecessary exploratory laparotomy [57][33], while mortality of secondary bacterial peritonitis can exceed 80% if treatment consists of antibiotics without surgical intervention [9].

5. Treatment

The standard treatment for SBP is prompt broad-spectrum antibiotic administration and albumin supplementation, especially in patients with renal impairment (RI) [54][34].5.1. Antibiotic Therapy

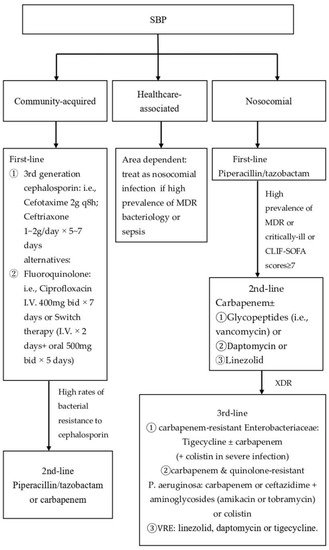

If SBP is suspected, antibiotic therapy must be initiated immediately after AF and culture to reduce complications and mortality [7]. Potentially nephrotoxic antibiotics (i.e., aminoglycosides) should be avoided [80][35] since patients with SBP are highly sensitive to aminoglycosides-related nephrotoxicity and fatal renal failure is common even at sub-toxic doses [46][29]. Two decades ago, most cases of SBP were attributed to third generation cephalosporin-sensitive Enterobacteriaceae. Now, risk factors, such as repeated hospitalizations, invasive procedures, and frequent exposure to antibiotics either as prophylaxis or as treatment [3], have led to the development of infections caused by MDR microorganisms. Bacterial resistance carries a 3.87-fold relative increased risk of mortality in patients with SBP [33][21]. Particularly, nosocomial SBP has been associated with multi-drug resistance (HR = 4.43) and poor outcome (50% in-hospital mortality). One prospective study demonstrated that failure of recommended empirical antibiotic regimens can have a negative impact on mortality [81][36]. Therefore, it is important to distinguish community-acquired SBP from healthcare-associated and nosocomial SBP, as well as consider the severity of infection and local resistance profile before implementing antibiotic therapy [54][34] (Figure 2). Subsequently, de-escalation according to bacterial susceptibility based on positive culture is recommended to minimize resistance selection pressure.

5.3. Albumin Supplement in Patients with Renal Impairment

5.2. Albumin Supplement in Patients with Renal Impairment

5.4. Discontinue NSBB in Patients with SBP

5.3. Discontinue NSBB in Patients with SBP

5.5. Other Novel Therapeutic Strategies

5.4. Other Novel Therapeutic Strategies

6. Conclusions

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) is a severe complication in cirrhosis patients with ascites. Clinical awareness, prompt diagnosis by exclusion of secondary bacterial peritonitis, and immediate treatment are necessary to reduce mortality and morbidity in this patient group. However, the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) microorganisms have changed ourthe understanding of SBP bacteriology and treatment. Antibiotic therapy specific to either community-acquired or nosocomial/healthcare-acquired SBP is ideal, while liver transplantation remains the definitive treatment following SBP. Prevention of SBP recurrence by antibiotic prophylaxis while patients wait for a liver transplant is therefore an important clinical issue. The poorly absorbed antibiotic rifaximin may be effective for both primary and secondary SBP prophylaxis, but additional prospective studies are required. Further development of non-antibiotic strategies based on pathogenic mechanisms are also urgently needed. Blind studies that avoid post-randomization dropout and consider clinically relevant outcomes, such as mortality, health-related quality of life, and decompensation events, are desired for future research. There are three types of SBP. Bacterial translocation from the GI tract is the most common source of SBP. Therefore, two thirds of SBP cases were caused by Gram-negative bacilli, almost exclusively Enterobacteriaceae. Escherichia coli (E. coli) is the most frequently isolated pathogen. However, a trend of Gram-positive cocci (GPC)-associated SBP has been demonstrated in recent years, representing a changing paradigm in the known bacteriology of SBP, especially in nosocomial SBP; other sources, such as transient bacteremia due to invasive procedures, can also lead to SBP Gram-positive cocci (GPC), such as Staphylococcus, Enterococcus, as well as multi-resistant bacteria have become common pathogens and have changed the conventional approach to treatment of SBP. Healthcare-associated and nosocomial SBP infections should prompt greater vigilance and consideration for alternative antibiotic coverage. Acid suppressive and beta-adrenergic antagonist therapies are strongly associated with SBP in at-risk individuals. A diagnostic paracentesis should be performed in all patients with cirrhosis and ascites who require emergency room care or hospitalization, who demonstrate or report signs/symptoms mentioned above in the clinical presentations, or who present gastrointestinal bleeding, in order to confirm evidence of SBP. Distinguishing SBP from secondary bacterial peritonitis is essential because the conditions require different therapeutic strategies. Since SBP may be regarded as the final clinical stage of liver cirrhosis [63][42], one-year overall mortality rates range from 53.9 [76][43] to 78% [64,76,79][43][44][45]. Liver transplantation should be seriously considered for SBP survivors who are good candidates for transplantation. The standard treatment for SBP is prompt broad-spectrum antibiotic administration and should be tailored according to either CAP or hospital-acquired, or to local resistance profiles. Albumin supplementation, especially in patients with renal impairment (RI) is also beneficial. Not all patients with cirrhosis and ascites require antibiotic prophylaxis, sometimes referred to as selective intestinal decontamination (SID). SID is associated with a reduced risk of bacterial infection [37,102,103,104][46][47][48][49] and mortality.References

- Wasmuth, E.; Kunz, D.; Yagmur, E.; Timmer-Stranghöner, A.; Vidacek, D.; Siewert, E.; Bach, J.; Geier, A.; Purucker, E.A.; Gressner, A.M. Patients with acute on chronic liver failure display ‘sepsis-like’immune paralysis. J. Hepatol. 2005, 42, 195–201.

- Wiest, ; Garcia‐Tsao, G. Bacterial translocation (BT) in cirrhosis. Hepatology 2005, 41, 422–433.

- Fernández, ; Navasa, M.; Gómez, J.; Colmenero, J.; Vila, J.; Arroyo, V.; Rodés, J. Bacterial infections in cirrhosis: Epidemiological changes with invasive procedures and norfloxacin prophylaxis. Hepatology 2002, 35, 140–148.

- Huang, H.; Lin, C.Y.; Sheen, I.S.; Chen, W.T.; Lin, T.N.; Ho, Y.P.; Chiu, C.T. Recurrence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients non-prophylactically treated with norfloxacin: Serum albumin as an easy but reliable predictive factor. Liver Int. 2011, 31, 184–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02377.x.

- Aithal, P.; Palaniyappan, N.; China, L.; Harmala, S.; Macken, L.; Ryan, J.M.; Wilkes, E.A.; Moore, K.; Leithead, J.A.; Hayes, P.C.; et al. Guidelines on the management of ascites in cirrhosis. Gut 2021, 70, 9–29. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321790.

- Garcia-Tsao, Current management of the complications of cirrhosis and portal hypertension: Variceal hemorrhage, ascites, and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology 2001, 120, 726–748. https://doi.org/10.1053/gast.2001.22580.

- Rimola, ; García-Tsao, G.; Navasa, M.; Piddock, L.J.; Planas, R.; Bernard, B.; Inadomi, J.M. Diagnosis, treatment and prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: A consensus document. J. Hepatol. 2000, 32, 142–153.

- Runyon, A.; Aasld. Introduction to the revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Practice Guideline management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis 2012. Hepatology 2013, 57, 1651–1653. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.26359.

- Rimola, ; Garcia-Tsao, G.; Navasa, M.; Piddock, L.J.; Planas, R.; Bernard, B.; Inadomi, J.M. Diagnosis, treatment and prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: A consensus document. International Ascites Club. J. Hepatol. 2000, 32, 142–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80201-9.

- Akriviadis, A.; Runyon, B.A. Utility of an algorithm in differentiating spontaneous from secondary bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology 1990, 98, 127–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(90)91300-u.

- Runyon, A.; Committee, A.P.G. Management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis: An update. Hepatology 2009, 49, 2087–2107. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.22853.

- Dever, B.; Sheikh, M.Y. Review article: Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis--bacteriology, diagnosis, treatment, risk factors and prevention. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 41, 1116–1131. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13172.

- Pinzello, ; Simonetti, R.G.; Craxi, A.; Di Piazza, S.; Spano, C.; Pagliaro, L. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: A prospective investigation in predominantly nonalcoholic cirrhotic patients. Hepatology 1983, 3, 545–549. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.1840030411.

- Fernandez, ; Navasa, M.; Planas, R.; Montoliu, S.; Monfort, D.; Soriano, G.; Vila, C.; Pardo, A.; Quintero, E.; Vargas, V.; et al. Primary prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis delays hepatorenal syndrome and improves survival in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2007, 133, 818–824. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.065.

- Navasa, ; Follo, A.; Llovet, J.M.; Clemente, G.; Vargas, V.; Rimola, A.; Marco, F.; Guarner, C.; Forne, M.; Planas, R.; et al. Randomized, comparative study of oral ofloxacin versus intravenous cefotaxime in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology 1996, 111, 1011–1017. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0016-5085(96)70069-0.

- Navasa, ; Follo, A.; Filella, X.; Jimenez, W.; Francitorra, A.; Planas, R.; Rimola, A.; Arroyo, V.; Rodes, J. Tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis: Relationship with the development of renal impairment and mortality. Hepatology 1998, 27, 1227–1232. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.510270507.

- Al-Ghamdi, ; Al-Harbi, N.; Mokhtar, H.; Daffallah, M.; Memon, Y.; Aljumah, A.A.; Sanai, F.M. Changes in the patterns and microbiology of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: Analysis of 200 cirrhotic patients. Acta Gastro Enterol. Belg. 2019, 82, 261–266.

- Na, H.; Kim, E.J.; Nam, E.Y.; Song, K.H.; Choe, P.G.; Park, W.B.; Bang, J.H.; Kim, E.S.; Park, S.W.; Kim, H.B.; et al. Comparison of clinical characteristics and outcomes of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and culture negative neutrocytic ascites. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 52, 199–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365521.2016.1245776.

- Fernandez, ; Navasa, M.; Gomez, J.; Colmenero, J.; Vila, J.; Arroyo, V.; Rodes, J. Bacterial infections in cirrhosis: Epidemiological changes with invasive procedures and norfloxacin prophylaxis. Hepatology 2002, 35, 140–148. https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.2002.30082.

- Runyon, A.; Canawati, H.N.; Akriviadis, E.A. Optimization of ascitic fluid culture technique. Gastroenterology 1988, 95, 1351–1355. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(88)90372-1.

- Oladimeji, A.; Temi, A.P.; Adekunle, A.E.; Taiwo, R.H.; Ayokunle, D.S. Prevalence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in liver cirrhosis with ascites. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2013, 15, 128. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2013.15.128.2702.

- Chu, M.; Chang, K.Y.; Liaw, Y.F. Prevalence and prognostic significance of bacterascites in cirrhosis with ascites. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1995, 40, 561–565. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02064369.

- Runyon, A.; Squier, S.; Borzio, M. Translocation of gut bacteria in rats with cirrhosis to mesenteric lymph nodes partially explains the pathogenesis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. J. Hepatol. 1994, 21, 792–796. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-8278(94)80241-6.

- Berg, D.; Garlington, A.W. Translocation of certain indigenous bacteria from the gastrointestinal tract to the mesenteric lymph nodes and other organs in a gnotobiotic mouse model. Infect. Immun. 1979, 23, 403–411. https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.23.2.403-411.1979.

- Vilela, G.; Thabut, D.; Rudler, M.; Bittencourt, P.L. Management of Complications of Portal Hypertension. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 2019, 6919284. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/6919284.

- Guarner, ; Runyon, B.A.; Young, S.; Heck, M.; Sheikh, M.Y. Intestinal bacterial overgrowth and bacterial translocation in cirrhotic rats with ascites. J. Hepatol. 1997, 26, 1372–1378. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80474-6.

- Cirera, ; Bauer, T.M.; Navasa, M.; Vila, J.; Grande, L.; Taura, P.; Fuster, J.; Garcia-Valdecasas, J.C.; Lacy, A.; Suarez, M.J.; et al. Bacterial translocation of enteric organisms in patients with cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 2001, 34, 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-8278(00)00013-1.

- Dunn, L.; Barke, R.A.; Knight, N.B.; Humphrey, E.W.; Simmons, R.L. Role of resident macrophages, peripheral neutrophils, and translymphatic absorption in bacterial clearance from the peritoneal cavity. Infect. Immun. 1985, 49, 257–264. https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.49.2.257-264.1985.

- Ruiz-Alcaraz, J.; Martinez-Banaclocha, H.; Marin-Sanchez, P.; Carmona-Martinez, V.; Iniesta-Albadalejo, M.A.; Tristan-Manzano, M.; Tapia-Abellan, A.; Garcia-Penarrubia, P.; Machado-Linde, F.; Pelegrin, P.; et al. Isolation of functional mature peritoneal macrophages from healthy humans. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2020, 98, 114–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/imcb.12305.

- Charles, A.; Janeway, J.; Travers, P.; Walport, M.; Shlomchik, M.J. Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease, 5th ; Garland Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2001.

- Huang, H.; Jeng, W.J.; Ho, Y.P.; Teng, W.; Hsieh, Y.C.; Chen, W.T.; Chen, Y.C.; Lin, H.H.; Sheen, I.S.; Lin, C.Y. Increased EMR2 expression on neutrophils correlates with disease severity and predicts overall mortality in cirrhotic patients. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38250. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38250.

- Rimola, ; Soto, R.; Bory, F.; Arroyo, V.; Piera, C.; Rodes, J. Reticuloendothelial system phagocytic activity in cirrhosis and its relation to bacterial infections and prognosis. Hepatology 1984, 4, 53–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.1840040109.

- Runyon, A. Low-protein-concentration ascitic fluid is predisposed to spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology 1986, 91, 1343–1346. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(86)90185-x.

- Hoefs, C.; Runyon, B.A. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Dis. Mon. 1985, 31, 1–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/0011-5029(85)90002-1.

- Wiest, ; Krag, A.; Gerbes, A. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: Recent guidelines and beyond. Gut 2012, 61, 297–310. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300779.

- Bhuva, ; Ganger, D.; Jensen, D. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: An update on evaluation, management, and prevention. Am. J. Med. 1994, 97, 169–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(94)90027-2.

- Runyon, A. Monomicrobial nonneutrocytic bacterascites: A variant of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Hepatology 1990, 12, 710–715. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.1840120415.

- Piroth, ; Pechinot, A.; Di Martino, V.; Hansmann, Y.; Putot, A.; Patry, I.; Hadou, T.; Jaulhac, B.; Chirouze, C.; Rabaud, C.; et al. Evolving epidemiology and antimicrobial resistance in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: A two-year observational study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 287. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-287.

- Gines, ; Rimola, A.; Planas, R.; Vargas, V.; Marco, F.; Almela, M.; Forne, M.; Miranda, M.L.; Llach, J.; Salmeron, J.M.; et al. Norfloxacin prevents spontaneous bacterial peritonitis recurrence in cirrhosis: Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Hepatology 1990, 12, 716–724. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.1840120416.

- Llovet, M.; Rodriguez-Iglesias, P.; Moitinho, E.; Planas, R.; Bataller, R.; Navasa, M.; Menacho, M.; Pardo, A.; Castells, A.; Cabre, E.; et al. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients with cirrhosis undergoing selective intestinal decontamination. A retrospective study of 229 spontaneous bacterial peritonitis episodes. J. Hepatol. 1997, 26, 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80014-1.

- Campillo, ; Dupeyron, C.; Richardet, J.P.; Mangeney, N.; Leluan, G. Epidemiology of severe hospital-acquired infections in patients with liver cirrhosis: Effect of long-term administration of norfloxacin. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1998, 26, 1066–1070. https://doi.org/10.1086/520273.

- Alexopoulou, ; Papadopoulos, N.; Eliopoulos, D.G.; Alexaki, A.; Tsiriga, A.; Toutouza, M.; Pectasides, D. Increasing frequency of gram-positive cocci and gram-negative multidrug-resistant bacteria in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Liver Int. 2013, 33, 975–981. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.12152.

- Fernandez, ; Acevedo, J.; Castro, M.; Garcia, O.; de Lope, C.R.; Roca, D.; Pavesi, M.; Sola, E.; Moreira, L.; Silva, A.; et al. Prevalence and risk factors of infections by multiresistant bacteria in cirrhosis: A prospective study. Hepatology 2012, 55, 1551–1561. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.25532.

- Reuken, A.; Pletz, M.W.; Baier, M.; Pfister, W.; Stallmach, A.; Bruns, T. Emergence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis due to enterococci—Risk factors and outcome in a 12-year retrospective study. Aliment Pharm. 2012, 35, 1199–1208. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05076.x.

- Alexopoulou, ; Vasilieva, L.; Agiasotelli, D.; Siranidi, K.; Pouriki, S.; Tsiriga, A.; Toutouza, M.; Dourakis, S.P. Extensively drug-resistant bacteria are an independent predictive factor of mortality in 130 patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis or spontaneous bacteremia. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 4049.

- Dupeyron, ; Campillo, S.B.; Mangeney, N.; Richardet, J.P.; Leluan, G. Carriage of Staphylococcus aureus and of gram-negative bacilli resistant to third-generation cephalosporins in cirrhotic patients: A prospective assessment of hospital-acquired infections. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2001, 22, 427–432. https://doi.org/10.1086/501929.

- Campillo, ; Richardet, J.P.; Kheo, T.; Dupeyron, C. Nosocomial spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and bacteremia in cirrhotic patients: Impact of isolate type on prognosis and characteristics of infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 35, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1086/340617.

- Such, ; Runyon, B.A. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1998, 27, 669–674; quiz 675–666. https://doi.org/10.1086/514940.

- Sheckman, ; Onderdonk, A.B.; Bartlett, J.G. Anaerobes in spontaneous peritonitis. Lancet 1977, 2, 1223. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(77)90456-1.

- Shi, ; Wu, D.; Wei, L.; Liu, S.; Zhao, P.; Tu, B.; Xie, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, L.; et al. Nosocomial and Community-Acquired Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis in patients with liver cirrhosis in China: Comparative Microbiology and Therapeutic Implications. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46025. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep46025.

- European Association for the Study of the EASL clinical practice guidelines on the management of ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 2010, 53, 397–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2010.05.004.

- Orman, S.; Hayashi, P.H.; Bataller, R.; Barritt, A.S.t. Paracentesis is associated with reduced mortality in patients hospitalized with cirrhosis and ascites. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 12, 496–503.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2013.08.025.

- Kim, J.; Tsukamoto, M.M.; Mathur, A.K.; Ghomri, Y.M.; Hou, L.A.; Sheibani, S.; Runyon, B.A. Delayed paracentesis is associated with increased in-hospital mortality in patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 109, 1436–1442. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2014.212.

- Grabau, M.; Crago, S.F.; Hoff, L.K.; Simon, J.A.; Melton, C.A.; Ott, B.J.; Kamath, P.S. Performance standards for therapeutic abdominal paracentesis. Hepatology 2004, 40, 484–488. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.20317.

- Runyon, A.; Umland, E.T.; Merlin, T. Inoculation of blood culture bottles with ascitic fluid. Improved detection of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Arch. Intern. Med. 1987, 147, 73–75.

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 406–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.024.

- Hoefs, C. Increase in ascites white blood cell and protein concentrations during diuresis in patients with chronic liver disease. Hepatology 1981, 1, 249–254. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.1840010310.

- Runyon, A.; Hoefs, J.C. Culture-negative neutrocytic ascites: A variant of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Hepatology 1984, 4, 1209–1211. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.1840040619.

- Garrison, N.; Cryer, H.M.; Howard, D.A.; Polk, H.C., Jr. Clarification of risk factors for abdominal operations in patients with hepatic cirrhosis. Ann. Surg. 1984, 199, 648–655. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-198406000-00003.

- Runyon, A.; Hoefs, J.C. Ascitic fluid analysis in the differentiation of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis from gastrointestinal tract perforation into ascitic fluid. Hepatology 1984, 4, 447–450. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.1840040316.

- Soriano, ; Castellote, J.; Alvarez, C.; Girbau, A.; Gordillo, J.; Baliellas, C.; Casas, M.; Pons, C.; Roman, E.M.; Maisterra, S.; et al. Secondary bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis: A retrospective study of clinical and analytical characteristics, diagnosis and management. J. Hepatol. 2010, 52, 39–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2009.10.012.

- Weil, ; Heurgue-Berlot, A.; Monnet, E.; Chassagne, S.; Cervoni, J.P.; Feron, T.; Grandvallet, C.; Muel, E.; Bronowicki, J.P.; Thiefin, G.; et al. Accuracy of calprotectin using the Quantum Blue Reader for the diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in liver cirrhosis. Hepatol. Res. 2019, 49, 72–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/hepr.13239.

- Lutz, ; Pfarr, K.; Nischalke, H.D.; Kramer, B.; Goeser, F.; Glassner, A.; Wolter, F.; Kokordelis, P.; Nattermann, J.; Sauerbruch, T.; et al. The ratio of calprotectin to total protein as a diagnostic and prognostic marker for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients with liver cirrhosis and ascites. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2015, 53, 2031–2039. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2015-0284.

- Gundling, ; Schmidtler, F.; Hapfelmeier, A.; Schulte, B.; Schmidt, T.; Pehl, C.; Schepp, W.; Seidl, H. Fecal calprotectin is a useful screening parameter for hepatic encephalopathy and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2011, 31, 1406–1415. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02577.x.

- Huang, H.; Tseng, H.J.; Amodio, P.; Chen, Y.L.; Wang, S.F.; Chang, S.H.; Hsieh, S.Y.; Lin, C.Y. Hepatic Encephalopathy and Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis Improve Cirrhosis Outcome Prediction: A Modified Seven-Stage Model as a Clinical Alternative to MELD. J. Pers. Med. 2020, 10, 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm10040186.

- Andreu, ; Sola, R.; Sitges-Serra, A.; Alia, C.; Gallen, M.; Vila, M.C.; Coll, S.; Oliver, M.I. Risk factors for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients with ascites. Gastroenterology 1993, 104, 1133–1138. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(93)90284-j.

- Runyon, A.; Morrissey, R.L.; Hoefs, J.C.; Wyle, F.A. Opsonic activity of human ascitic fluid: A potentially important protective mechanism against spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Hepatology 1985, 5, 634–637. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.1840050419.

- Bernard, ; Cadranel, J.F.; Valla, D.; Escolano, S.; Jarlier, V.; Opolon, P. Prognostic significance of bacterial infection in bleeding cirrhotic patients: A prospective study. Gastroenterology 1995, 108, 1828–1834. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(95)90146-9.

- Bernard, ; Grange, J.D.; Khac, E.N.; Amiot, X.; Opolon, P.; Poynard, T. Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of bacterial infections in cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal bleeding: A meta-analysis. Hepatology 1999, 29, 1655–1661. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.510290608.

- Martinez, ; Hernandez-Gea, V.; Rodriguez-de-Santiago, E.; Tellez, L.; Procopet, B.; Giraldez, A.; Amitrano, L.; Villanueva, C.; Thabut, D.; Ibanez-Samaniego, L.; et al. Bacterial infections in patients with acute variceal bleeding in the era of antibiotic prophylaxis. J. Hepatol. 2021, 75, 342–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2021.03.026.

- Deshpande, ; Pasupuleti, V.; Thota, P.; Pant, C.; Mapara, S.; Hassan, S.; Rolston, D.D.; Sferra, T.J.; Hernandez, A.V. Acid-suppressive therapy is associated with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients: A meta-analysis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 28, 235–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.12065.

- Trikudanathan, ; Israel, J.; Cappa, J.; O’Sullivan, D.M. Association between proton pump inhibitors and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2011, 65, 674–678. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02650.x.

- O’Leary, G.; Reddy, K.R.; Wong, F.; Kamath, P.S.; Patton, H.M.; Biggins, S.W.; Fallon, M.B.; Garcia-Tsao, G.; Subramanian, R.M.; Malik, R.; et al. Long-term use of antibiotics and proton pump inhibitors predict development of infections in patients with cirrhosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 13, 753–759.e1-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2014.07.060.

- Alaniz, ; Regal, R.E. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: A review of treatment options. P T 2009, 34, 204–210.

- Senzolo, ; Cholongitas, E.; Burra, P.; Leandro, G.; Thalheimer, U.; Patch, D.; Burroughs, A.K. beta-Blockers protect against spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients: A meta-analysis. Liver Int. 2009, 29, 1189–1193. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02038.x.

- Senkerikova, ; de Mare-Bredemeijer, E.; Frankova, S.; Roelen, D.; Visseren, T.; Trunecka, P.; Spicak, J.; Metselaar, H.; Jirsa, M.; Kwekkeboom, J.; et al. Genetic variation in TNFA predicts protection from severe bacterial infections in patients with end-stage liver disease awaiting liver transplantation. J. Hepatol. 2014, 60, 773–781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2013.12.011.

- Tito, ; Rimola, A.; Gines, P.; Llach, J.; Arroyo, V.; Rodes, J. Recurrence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis: Frequency and predictive factors. Hepatology 1988, 8, 27–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.1840080107.

- Hung, H.; Tsai, C.C.; Hsieh, Y.H.; Tsai, C.C. The long-term mortality of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients: A 3-year nationwide cohort study. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 26, 159–162. https://doi.org/10.5152/tjg.2015.4829.

- Tandon, ; Garcia-Tsao, G. Renal dysfunction is the most important independent predictor of mortality in cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011, 9, 260–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2010.11.038.

- Karvellas, J.; Abraldes, J.G.; Arabi, Y.M.; Kumar, A.; Cooperative Antimicrobial Therapy of Septic Shock Database Research Group. Appropriate and timely antimicrobial therapy in cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis-associated septic shock: A retrospective cohort study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 41, 747–757. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13135.

- Bac, J. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: An indication for liver transplantation? Scand. J. Gastroenterol. Suppl. 1996, 218, 38–42. https://doi.org/10.3109/00365529609094729.

- Cabrera, ; Arroyo, V.; Ballesta, A.M.; Rimola, A.; Gual, J.; Elena, M.; Rodes, J. Aminoglycoside nephrotoxicity in cirrhosis. Value of urinary beta 2-microglobulin to discriminate functional renal failure from acute tubular damage. Gastroenterology 1982, 82, 97–105.

- Umgelter, ; Reindl, W.; Miedaner, M.; Schmid, R.M.; Huber, W. Failure of current antibiotic first-line regimens and mortality in hospitalized patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Infection 2009, 37, 2–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-008-8060-9.

- Chavez-Tapia, C.; Soares-Weiser, K.; Brezis, M.; Leibovici, L. Antibiotics for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, CD002232. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002232.pub2.

- Felisart, ; Rimola, A.; Arroyo, V.; Perez-Ayuso, R.M.; Quintero, E.; Gines, P.; Rodes, J. Cefotaxime is more effective than is ampicillin-tobramycin in cirrhotics with severe infections. Hepatology 1985, 5, 457–462. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.1840050319.

- Rimola, ; Salmeron, J.M.; Clemente, G.; Rodrigo, L.; Obrador, A.; Miranda, M.L.; Guarner, C.; Planas, R.; Sola, R.; Vargas, V.; et al. Two different dosages of cefotaxime in the treatment of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis: Results of a prospective, randomized, multicenter study. Hepatology 1995, 21, 674–679.

- Runyon, A.; McHutchison, J.G.; Antillon, M.R.; Akriviadis, E.A.; Montano, A.A. Short-course versus long-course antibiotic treatment of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. A randomized controlled study of 100 patients. Gastroenterology 1991, 100, 1737–1742. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(91)90677-d.

- Fernandez, ; Ruiz del Arbol, L.; Gomez, C.; Durandez, R.; Serradilla, R.; Guarner, C.; Planas, R.; Arroyo, V.; Navasa, M. Norfloxacin vs ceftriaxone in the prophylaxis of infections in patients with advanced cirrhosis and hemorrhage. Gastroenterology 2006, 131, 1049–1056; quiz 1285. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2006.07.010.

- Mazer, ; Tapper, E.B.; Piatkowski, G.; Lai, M. The need for antibiotic stewardship and treatment standardization in the care of cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis—A retrospective cohort study examining the effect of ceftriaxone dosing. F1000Research 2014, 3, 57. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.3-57.v2.

- Baskol, ; Gursoy, S.; Baskol, G.; Ozbakir, O.; Guven, K.; Yucesoy, M. Five days of ceftriaxone to treat culture negative neutrocytic ascites in cirrhotic patients. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2003, 37, 403–405. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004836-200311000-00011.

- Terg, ; Cobas, S.; Fassio, E.; Landeira, G.; Rios, B.; Vasen, W.; Abecasis, R.; Rios, H.; Guevara, M. Oral ciprofloxacin after a short course of intravenous ciprofloxacin in the treatment of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: Results of a multicenter, randomized study. J. Hepatol. 2000, 33, 564–569. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0641.2000.033004564.x.

- Angeli, ; Guarda, S.; Fasolato, S.; Miola, E.; Craighero, R.; Piccolo, F.; Antona, C.; Brollo, L.; Franchin, M.; Cillo, U.; et al. Switch therapy with ciprofloxacin vs. intravenous ceftazidime in the treatment of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients with cirrhosis: Similar efficacy at lower cost. Aliment.Pharmacol.Ther. 2006, 23, 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02706.x.

- Ariza, ; Castellote, J.; Lora-Tamayo, J.; Girbau, A.; Salord, S.; Rota, R.; Ariza, J.; Xiol, X. Risk factors for resistance to ceftriaxone and its impact on mortality in community, healthcare and nosocomial spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. J. Hepatol. 2012, 56, 825–832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2011.11.010.

- Piano, ; Fasolato, S.; Salinas, F.; Romano, A.; Tonon, M.; Morando, F.; Cavallin, M.; Gola, E.; Sticca, A.; Loregian, A.; et al. The empirical antibiotic treatment of nosocomial spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: Results of a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Hepatology 2016, 63, 1299–1309. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27941.

- Kim, W.; Yoon, J.S.; Park, J.; Jung, Y.J.; Lee, J.S.; Song, J.; Lee, H.A.; Seo, Y.S.; Lee, M.; Park, J.M.; et al. Empirical Treatment With Carbapenem vs Third-generation Cephalosporin for Treatment of Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 19, 976–986.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2020.06.046.

- Piano, ; Brocca, A.; Mareso, S.; Angeli, P. Infections complicating cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2018, 38 (Suppl. 1), 126–133. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.13645.

- Falcone, ; Russo, A.; Pacini, G.; Merli, M.; Venditti, M. Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis Due to Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus in a Patient with Cirrhosis: The Potential Role for Daptomycin and Review of the Literature. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2015, 7, 6127. https://doi.org/10.4081/idr.2015.6127.

- Koulenti, D.; Xu, E.; Mok, I.Y.S.; Song, A.; Karageorgopoulos, D.E.; Armaganidis, A.; Lipman, J.; Tsiodras, S. Novel Antibiotics for Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Positive Microorganisms. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7080270.

- Sort, ; Navasa, M.; Arroyo, V.; Aldeguer, X.; Planas, R.; Ruiz-del-Arbol, L.; Castells, L.; Vargas, V.; Soriano, G.; Guevara, M.; et al. Effect of intravenous albumin on renal impairment and mortality in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 403–409. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199908053410603.

- Sigal, H.; Stanca, C.M.; Fernandez, J.; Arroyo, V.; Navasa, M. Restricted use of albumin for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gut 2007, 56, 597–599. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2006.113050.

- Salerno, ; Navickis, R.J.; Wilkes, M.M. Albumin infusion improves outcomes of patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 11, 123–130.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2012.11.007.

- Mandorfer, ; Bota, S.; Schwabl, P.; Bucsics, T.; Pfisterer, N.; Kruzik, M.; Hagmann, M.; Blacky, A.; Ferlitsch, A.; Sieghart, W.; et al. Nonselective beta blockers increase risk for hepatorenal syndrome and death in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 1680–1690.e1. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2014.03.005.

- Pampalone, ; Vitale, G.; Gruttadauria, S.; Amico, G.; Iannolo, G.; Douradinha, B.; Mularoni, A.; Conaldi, P.G.; Pietrosi, G. Human Amnion-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: A New Potential Treatment for Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales in Decompensated Cirrhosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 857. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23020857.

- Soriano, ; Guarner, C.; Teixido, M.; Such, J.; Barrios, J.; Enriquez, J.; Vilardell, F. Selective intestinal decontamination prevents spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology 1991, 100, 477–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(91)90219-b.

- Soriano, ; Guarner, C.; Tomas, A.; Villanueva, C.; Torras, X.; Gonzalez, D.; Sainz, S.; Anguera, A.; Cusso, X.; Balanzo, J.; et al. Norfloxacin prevents bacterial infection in cirrhotics with gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology 1992, 103, 1267–1272. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(92)91514-5.

- Grange, D.; Roulot, D.; Pelletier, G.; Pariente, E.A.; Denis, J.; Ink, O.; Blanc, P.; Richardet, J.P.; Vinel, J.P.; Delisle, F.; et al. Norfloxacin primary prophylaxis of bacterial infections in cirrhotic patients with ascites: A double-blind randomized trial. J. Hepatol. 1998, 29, 430–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80061-5.

- Soares-Weiser, ; Brezis, M.; Tur-Kaspa, R.; Paul, M.; Yahav, J.; Leibovici, L. Antibiotic prophylaxis of bacterial infections in cirrhotic inpatients: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2003, 38, 193–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365520310000690.

- Terg, ; Fassio, E.; Guevara, M.; Cartier, M.; Longo, C.; Lucero, R.; Landeira, C.; Romero, G.; Dominguez, N.; Munoz, A.; et al. Ciprofloxacin in primary prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: A randomized, placebo-controlled study. J. Hepatol. 2008, 48, 774–779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2008.01.024.

- Ortiz, ; Vila, M.C.; Soriano, G.; Minana, J.; Gana, J.; Mirelis, B.; Novella, M.T.; Coll, S.; Sabat, M.; Andreu, M.; et al. Infections caused by Escherichia coli resistant to norfloxacin in hospitalized cirrhotic patients. Hepatology 1999, 29, 1064–1069. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.510290406.

- Tandon, ; Delisle, A.; Topal, J.E.; Garcia-Tsao, G. High prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections among patients with cirrhosis at a US liver center. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 10, 1291–1298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2012.08.017.

- Fernandez, ; Prado, V.; Trebicka, J.; Amoros, A.; Gustot, T.; Wiest, R.; Deulofeu, C.; Garcia, E.; Acevedo, J.; Fuhrmann, V.; et al. Multidrug-resistant bacterial infections in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and with acute-on-chronic liver failure in Europe. J. Hepatol. 2019, 70, 398–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.10.027.

- Loomba, ; Wesley, R.; Bain, A.; Csako, G.; Pucino, F. Role of fluoroquinolones in the primary prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: Meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 7, 487–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2008.12.018.

- Saab, ; Hernandez, J.C.; Chi, A.C.; Tong, M.J. Oral antibiotic prophylaxis reduces spontaneous bacterial peritonitis occurrence and improves short-term survival in cirrhosis: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 104, 993–1001; quiz 1002. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2009.3.

- Komolafe, ; Roberts, D.; Freeman, S.C.; Wilson, P.; Sutton, A.J.; Cooper, N.J.; Pavlov, C.S.; Milne, E.J.; Hawkins, N.; Cowlin, M.; et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in people with liver cirrhosis: A network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 1, CD013125. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013125.pub2.

- Fernandez, ; Tandon, P.; Mensa, J.; Garcia-Tsao, G. Antibiotic prophylaxis in cirrhosis: Good and bad. Hepatology 2016, 63, 2019–2031. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.28330.

- Jalan, ; Fernandez, J.; Wiest, R.; Schnabl, B.; Moreau, R.; Angeli, P.; Stadlbauer, V.; Gustot, T.; Bernardi, M.; Canton, R.; et al. Bacterial infections in cirrhosis: A position statement based on the EASL Special Conference 2013. J. Hepatol. 2014, 60, 1310–1324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2014.01.024.

- Hou, C.; Lin, H.C.; Liu, T.T.; Kuo, B.I.; Lee, F.Y.; Chang, F.Y.; Lee, S.D. Antibiotic prophylaxis after endoscopic therapy prevents rebleeding in acute variceal hemorrhage: A randomized trial. Hepatology 2004, 39, 746–753. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.20126.

- Chavez-Tapia, C.; Barrientos-Gutierrez, T.; Tellez-Avila, F.; Soares-Weiser, K.; Mendez-Sanchez, N.; Gluud, C.; Uribe, M. Meta-analysis: Antibiotic prophylaxis for cirrhotic patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding—An updated Cochrane review. Aliment. Pharm. 2011, 34, 509–518. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04746.x.

- de Franchis, ; Bosch, J.; Garcia-Tsao, G.; Reiberger, T.; Ripoll, C.; Baveno, V.I.I.F. Baveno VII—Renewing consensus in portal hypertension. J. Hepatol. 2022, 76, 959–974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2021.12.022.

- Garcia-Tsao, ; Abraldes, J.G.; Berzigotti, A.; Bosch, J. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: Risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology 2017, 65, 310–335. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.28906.

- Bauer, M.; Follo, A.; Navasa, M.; Vila, J.; Planas, R.; Clemente, G.; Vargas, V.; Bory, F.; Vaquer, P.; Rodes, J. Daily norfloxacin is more effective than weekly rufloxacin in prevention of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis recurrence. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2002, 47, 1356–1361. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1015386901343.

- Goel, ; Rahim, U.; Nguyen, L.H.; Stave, C.; Nguyen, M.H. Systematic review with meta-analysis: Rifaximin for the prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 46, 1029–1036. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.14361.

- Terg, ; Llano, K.; Cobas, S.M.; Brotto, C.; Barrios, A.; Levi, D.; Wasen, W.; Bartellini, M.A. Effects of oral ciprofloxacin on aerobic gram-negative fecal flora in patients with cirrhosis: Results of short- and long-term administration, with daily and weekly dosages. J. Hepatol. 1998, 29, 437–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80062-7.

References

- Wasmuth, H.E.; Kunz, D.; Yagmur, E.; Timmer-Stranghöner, A.; Vidacek, D.; Siewert, E.; Bach, J.; Geier, A.; Purucker, E.A.; Gressner, A.M. Patients with acute on chronic liver failure display ‘sepsis-like’immune paralysis. J. Hepatol. 2005, 42, 195–201.

- Wiest, R.; Garcia-Tsao, G. Bacterial translocation (BT) in cirrhosis. Hepatology 2005, 41, 422–433.

- Fernández, J.; Navasa, M.; Gómez, J.; Colmenero, J.; Vila, J.; Arroyo, V.; Rodés, J. Bacterial infections in cirrhosis: Epidemiological changes with invasive procedures and norfloxacin prophylaxis. Hepatology 2002, 35, 140–148.

- Huang, C.H.; Lin, C.Y.; Sheen, I.S.; Chen, W.T.; Lin, T.N.; Ho, Y.P.; Chiu, C.T. Recurrence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients non-prophylactically treated with norfloxacin: Serum albumin as an easy but reliable predictive factor. Liver Int. 2011, 31, 184–191.

- Aithal, G.P.; Palaniyappan, N.; China, L.; Harmala, S.; Macken, L.; Ryan, J.M.; Wilkes, E.A.; Moore, K.; Leithead, J.A.; Hayes, P.C.; et al. Guidelines on the management of ascites in cirrhosis. Gut 2021, 70, 9–29.

- Garcia-Tsao, G. Current management of the complications of cirrhosis and portal hypertension: Variceal hemorrhage, ascites, and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology 2001, 120, 726–748.

- Rimola, A.; García-Tsao, G.; Navasa, M.; Piddock, L.J.; Planas, R.; Bernard, B.; Inadomi, J.M. Diagnosis, treatment and prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: A consensus document. J. Hepatol. 2000, 32, 142–153.

- Runyon, B.A.; AASLD. Introduction to the revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Practice Guideline management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis 2012. Hepatology 2013, 57, 1651–1653.

- Akriviadis, E.A.; Runyon, B.A. Utility of an algorithm in differentiating spontaneous from secondary bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology 1990, 98, 127–133.

- Runyon, B.A.; Committee, A.P.G. Management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis: An update. Hepatology 2009, 49, 2087–2107.

- Runyon, B.A.; Squier, S.; Borzio, M. Translocation of gut bacteria in rats with cirrhosis to mesenteric lymph nodes partially explains the pathogenesis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. J. Hepatol. 1994, 21, 792–796.

- Berg, R.D.; Garlington, A.W. Translocation of certain indigenous bacteria from the gastrointestinal tract to the mesenteric lymph nodes and other organs in a gnotobiotic mouse model. Infect. Immun. 1979, 23, 403–411.

- Vilela, E.G.; Thabut, D.; Rudler, M.; Bittencourt, P.L. Management of Complications of Portal Hypertension. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 2019, 6919284.

- Dunn, D.L.; Barke, R.A.; Knight, N.B.; Humphrey, E.W.; Simmons, R.L. Role of resident macrophages, peripheral neutrophils, and translymphatic absorption in bacterial clearance from the peritoneal cavity. Infect. Immun. 1985, 49, 257–264.

- Ruiz-Alcaraz, A.J.; Martinez-Banaclocha, H.; Marin-Sanchez, P.; Carmona-Martinez, V.; Iniesta-Albadalejo, M.A.; Tristan-Manzano, M.; Tapia-Abellan, A.; Garcia-Penarrubia, P.; Machado-Linde, F.; Pelegrin, P.; et al. Isolation of functional mature peritoneal macrophages from healthy humans. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2020, 98, 114–126.

- Charles, A.; Janeway, J.; Travers, P.; Walport, M.; Shlomchik, M.J. Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease, 5th ed.; Garland Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2001.

- Huang, C.H.; Jeng, W.J.; Ho, Y.P.; Teng, W.; Hsieh, Y.C.; Chen, W.T.; Chen, Y.C.; Lin, H.H.; Sheen, I.S.; Lin, C.Y. Increased EMR2 expression on neutrophils correlates with disease severity and predicts overall mortality in cirrhotic patients. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38250.

- Rimola, A.; Soto, R.; Bory, F.; Arroyo, V.; Piera, C.; Rodes, J. Reticuloendothelial system phagocytic activity in cirrhosis and its relation to bacterial infections and prognosis. Hepatology 1984, 4, 53–58.

- Runyon, B.A. Low-protein-concentration ascitic fluid is predisposed to spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology 1986, 91, 1343–1346.

- Hoefs, J.C.; Runyon, B.A. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Dis. Mon. 1985, 31, 1–48.

- Wiest, R.; Krag, A.; Gerbes, A. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: Recent guidelines and beyond. Gut 2012, 61, 297–310.

- Oladimeji, A.A.; Temi, A.P.; Adekunle, A.E.; Taiwo, R.H.; Ayokunle, D.S. Prevalence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in liver cirrhosis with ascites. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2013, 15, 128.

- Bhuva, M.; Ganger, D.; Jensen, D. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: An update on evaluation, management, and prevention. Am. J. Med. 1994, 97, 169–175.

- Runyon, B.A. Monomicrobial nonneutrocytic bacterascites: A variant of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Hepatology 1990, 12, 710–715.

- Alexopoulou, A.; Papadopoulos, N.; Eliopoulos, D.G.; Alexaki, A.; Tsiriga, A.; Toutouza, M.; Pectasides, D. Increasing frequency of gram-positive cocci and gram-negative multidrug-resistant bacteria in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Liver Int. 2013, 33, 975–981.

- Fernandez, J.; Acevedo, J.; Castro, M.; Garcia, O.; de Lope, C.R.; Roca, D.; Pavesi, M.; Sola, E.; Moreira, L.; Silva, A.; et al. Prevalence and risk factors of infections by multiresistant bacteria in cirrhosis: A prospective study. Hepatology 2012, 55, 1551–1561.

- Dever, J.B.; Sheikh, M.Y. Review article: Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis--bacteriology, diagnosis, treatment, risk factors and prevention. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 41, 1116–1131.

- Reuken, P.A.; Pletz, M.W.; Baier, M.; Pfister, W.; Stallmach, A.; Bruns, T. Emergence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis due to enterococci—Risk factors and outcome in a 12-year retrospective study. Aliment Pharm. 2012, 35, 1199–1208.

- Such, J.; Runyon, B.A. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1998, 27, 669–674, quiz 675–666.

- Sheckman, P.; Onderdonk, A.B.; Bartlett, J.G. Anaerobes in spontaneous peritonitis. Lancet 1977, 2, 1223.

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines on the management of ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 2010, 53, 397–417.

- Hoefs, J.C. Increase in ascites white blood cell and protein concentrations during diuresis in patients with chronic liver disease. Hepatology 1981, 1, 249–254.

- Garrison, R.N.; Cryer, H.M.; Howard, D.A.; Polk, H.C., Jr. Clarification of risk factors for abdominal operations in patients with hepatic cirrhosis. Ann. Surg. 1984, 199, 648–655.

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 406–460.

- Cabrera, J.; Arroyo, V.; Ballesta, A.M.; Rimola, A.; Gual, J.; Elena, M.; Rodes, J. Aminoglycoside nephrotoxicity in cirrhosis. Value of urinary beta 2-microglobulin to discriminate functional renal failure from acute tubular damage. Gastroenterology 1982, 82, 97–105.

- Umgelter, A.; Reindl, W.; Miedaner, M.; Schmid, R.M.; Huber, W. Failure of current antibiotic first-line regimens and mortality in hospitalized patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Infection 2009, 37, 2–8.

- Sort, P.; Navasa, M.; Arroyo, V.; Aldeguer, X.; Planas, R.; Ruiz-del-Arbol, L.; Castells, L.; Vargas, V.; Soriano, G.; Guevara, M.; et al. Effect of intravenous albumin on renal impairment and mortality in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 403–409.

- Sigal, S.H.; Stanca, C.M.; Fernandez, J.; Arroyo, V.; Navasa, M. Restricted use of albumin for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gut 2007, 56, 597–599.

- Salerno, F.; Navickis, R.J.; Wilkes, M.M. Albumin infusion improves outcomes of patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 11, 123–130.e1.

- Mandorfer, M.; Bota, S.; Schwabl, P.; Bucsics, T.; Pfisterer, N.; Kruzik, M.; Hagmann, M.; Blacky, A.; Ferlitsch, A.; Sieghart, W.; et al. Nonselective beta blockers increase risk for hepatorenal syndrome and death in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 1680–1690.e1.

- Pampalone, M.; Vitale, G.; Gruttadauria, S.; Amico, G.; Iannolo, G.; Douradinha, B.; Mularoni, A.; Conaldi, P.G.; Pietrosi, G. Human Amnion-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: A New Potential Treatment for Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales in Decompensated Cirrhosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 857.

- Huang, C.H.; Tseng, H.J.; Amodio, P.; Chen, Y.L.; Wang, S.F.; Chang, S.H.; Hsieh, S.Y.; Lin, C.Y. Hepatic Encephalopathy and Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis Improve Cirrhosis Outcome Prediction: A Modified Seven-Stage Model as a Clinical Alternative to MELD. J. Pers. Med. 2020, 10, 186.

- Hung, T.H.; Tsai, C.C.; Hsieh, Y.H.; Tsai, C.C. The long-term mortality of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients: A 3-year nationwide cohort study. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 26, 159–162.

- Andreu, M.; Sola, R.; Sitges-Serra, A.; Alia, C.; Gallen, M.; Vila, M.C.; Coll, S.; Oliver, M.I. Risk factors for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients with ascites. Gastroenterology 1993, 104, 1133–1138.

- Bac, D.J. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: An indication for liver transplantation? Scand. J. Gastroenterol. Suppl. 1996, 218, 38–42.

- Gines, P.; Rimola, A.; Planas, R.; Vargas, V.; Marco, F.; Almela, M.; Forne, M.; Miranda, M.L.; Llach, J.; Salmeron, J.M.; et al. Norfloxacin prevents spontaneous bacterial peritonitis recurrence in cirrhosis: Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Hepatology 1990, 12, 716–724.

- Soriano, G.; Guarner, C.; Teixido, M.; Such, J.; Barrios, J.; Enriquez, J.; Vilardell, F. Selective intestinal decontamination prevents spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology 1991, 100, 477–481.

- Soriano, G.; Guarner, C.; Tomas, A.; Villanueva, C.; Torras, X.; Gonzalez, D.; Sainz, S.; Anguera, A.; Cusso, X.; Balanzo, J.; et al. Norfloxacin prevents bacterial infection in cirrhotics with gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology 1992, 103, 1267–1272.

- Grange, J.D.; Roulot, D.; Pelletier, G.; Pariente, E.A.; Denis, J.; Ink, O.; Blanc, P.; Richardet, J.P.; Vinel, J.P.; Delisle, F.; et al. Norfloxacin primary prophylaxis of bacterial infections in cirrhotic patients with ascites: A double-blind randomized trial. J. Hepatol. 1998, 29, 430–436.