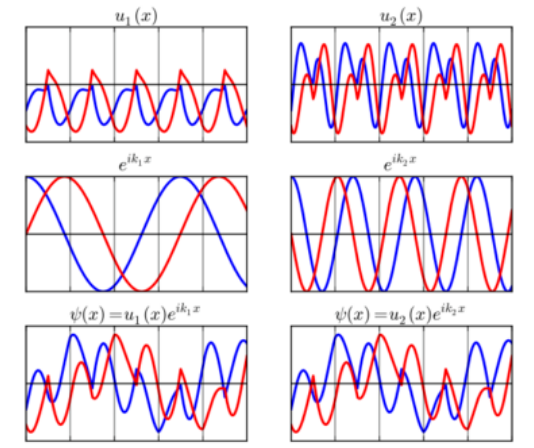

A Bloch wave (also called Bloch state or Bloch function or Bloch wavefunction), named after Swiss physicist Felix Bloch, is a kind of wave function which can be written as a plane wave modulated by a periodic function. By definition, if a wave is a Bloch wave, its wavefunction can be written in the form: where [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{r} }[/math] is position, [math]\displaystyle{ \psi }[/math] is the Bloch wave, [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] is a periodic function with the same periodicity as the crystal, the wave vector [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{k} }[/math] is the crystal momentum vector, [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{e} }[/math] is Euler's number, and [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{i} }[/math] is the imaginary unit. Bloch waves are important in solid-state physics, where they are often used to describe an electron in a crystal. This application is motivated by Bloch's theorem, which states that the energy eigenstates for an electron in a crystal can be written as Bloch waves (more precisely, it states that the electron wave functions in a crystal have a basis consisting entirely of Bloch wave energy eigenstates). This fact underlies the concept of electronic band structures. These Bloch wave energy eigenstates are written with subscripts as [math]\displaystyle{ \psi_{n\mathbf{k}} }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] is a discrete index, called the band index, which is present because there are many different Bloch waves with the same [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{k} }[/math] (each has a different periodic component [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math]). Within a band (i.e., for fixed [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]), [math]\displaystyle{ \psi_{n\mathbf{k}} }[/math] varies continuously with [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{k} }[/math], as does its energy. Also, for any reciprocal lattice vector [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{K} }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \psi_{n\mathbf{k}}=\psi_{n(\mathbf{k+K})} }[/math]. Therefore, all distinct Bloch waves occur for values of [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{k} }[/math] which fall within the first Brillouin zone of the reciprocal lattice.

- periodic function

- plane wave

- crystal

1. Applications and Consequences

1.1. Applicability

The most common example of Bloch's theorem is describing electrons in a crystal. However, a Bloch-wave description applies more generally to any wave-like phenomenon in a periodic medium. For example, a periodic dielectric structure in electromagnetism leads to photonic crystals, and a periodic acoustic medium leads to phononic crystals. It is generally treated in the various forms of the dynamical theory of diffraction.

1.2. Wave Vector

Suppose an electron is in a Bloch state

- [math]\displaystyle{ \psi ( \mathbf{r} ) = \mathrm{e}^{ \mathrm{i} \mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{r} } u ( \mathbf{r} ) , }[/math]

where u is periodic with the same periodicity as the crystal lattice. The actual quantum state of the electron is entirely determined by [math]\displaystyle{ \psi }[/math], not k or u directly. This is important because k and u are not unique. Specifically, if [math]\displaystyle{ \psi }[/math] can be written as above using k, it can also be written using (k + K), where K is any reciprocal lattice vector (see figure at right). Therefore, wave vectors that differ by a reciprocal lattice vector are equivalent, in the sense that they characterize the same set of Bloch states.

The first Brillouin zone is a restricted set of values of k with the property that no two of them are equivalent, yet every possible k is equivalent to one (and only one) vector in the first Brillouin zone. Therefore, if we restrict k to the first Brillouin zone, then every Bloch state has a unique k. Therefore, the first Brillouin zone is often used to depict all of the Bloch states without redundancy, for example in a band structure, and it is used for the same reason in many calculations.

When k is multiplied by the reduced Planck's constant, it equals the electron's crystal momentum. Related to this, the group velocity of an electron can be calculated based on how the energy of a Bloch state varies with k; for more details see crystal momentum.

1.3. Detailed Example

For a detailed example in which the consequences of Bloch's theorem are worked out in a specific situation, see the article: Particle in a one-dimensional lattice (periodic potential).

2. Proof of Bloch's Theorem

Next, we prove Bloch's theorem:

-

- For electrons in a perfect crystal, there is a basis of wavefunctions with the properties:

- Each of these wavefunctions is an energy eigenstate

- Each of these wavefunctions is a Bloch wave, meaning that this wavefunction [math]\displaystyle{ \psi }[/math] can be written in the form

-

- [math]\displaystyle{ \psi(\mathbf{r}) = \mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i}\mathbf{k}\cdot\mathbf{r}} u(\mathbf{r}) }[/math]

-

- where u has the same periodicity as the atomic structure of the crystal.

-

- where u has the same periodicity as the atomic structure of the crystal.

-

- [math]\displaystyle{ \psi(\mathbf{r}) = \mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i}\mathbf{k}\cdot\mathbf{r}} u(\mathbf{r}) }[/math]

- For electrons in a perfect crystal, there is a basis of wavefunctions with the properties:

2.1. Preliminaries: Crystal Symmetries, Lattice, and Reciprocal Lattice

The defining property of a crystal is translational symmetry, which means that if the crystal is shifted an appropriate amount, it winds up with all its atoms in the same places. (A finite-size crystal cannot have perfect translational symmetry, but it is a useful approximation.)

A three-dimensional crystal has three primitive lattice vectors a1, a2, a3. If the crystal is shifted by any of these three vectors, or a combination of them of the form

- [math]\displaystyle{ n_1 \mathbf{a}_1 + n_2 \mathbf{a}_2 + n_3 \mathbf{a}_3 }[/math]

where ni are three integers, then the atoms end up in the same set of locations as they started.

Another helpful ingredient in the proof is the reciprocal lattice vectors. These are three vectors b1, b2, b3 (with units of inverse length), with the property that ai · bi = 2π, but ai · bj = 0 when i ≠ j. (For the formula for bi, see reciprocal lattice vector.)

2.2. Lemma about Translation Operators

Let [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{T}_{n_1,n_2,n_3} \! }[/math] denote a translation operator that shifts every wave function by the amount n1a1 + n2a2 + n3a3 (as above, nj are integers). The following fact is helpful for the proof of Bloch's theorem:

-

- Lemma: If a wavefunction [math]\displaystyle{ \psi }[/math] is an eigenstate of all of the translation operators (simultaneously), then [math]\displaystyle{ \psi }[/math] is a Bloch wave.

- Lemma: If a wavefunction [math]\displaystyle{ \psi }[/math] is an eigenstate of all of the translation operators (simultaneously), then [math]\displaystyle{ \psi }[/math] is a Bloch wave.

Proof: Assume that we have a wavefunction [math]\displaystyle{ \psi }[/math] which is an eigenstate of all the translation operators. As a special case of this,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \psi(\mathbf{r}+\mathbf{a}_j) = C_j \psi(\mathbf{r}) }[/math]

for j = 1, 2, 3, where Cj are three numbers (the eigenvalues) which do not depend on r. It is helpful to write the numbers Cj in a different form, by choosing three numbers θ1, θ2, θ3 with e2πiθj = Cj:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \psi(\mathbf{r}+\mathbf{a}_j) = \mathrm{e}^{2 \pi \mathrm{i} \theta_j} \psi(\mathbf{r}) }[/math]

Again, the θj are three numbers which do not depend on r. Define k = θ1b1 + θ2b2 + θ3b3, where bj are the reciprocal lattice vectors (see above). Finally, define

- [math]\displaystyle{ u(\mathbf{r}) = \mathrm{e}^{-\mathrm{i} \mathbf{k}\cdot\mathbf{r}} \psi(\mathbf{r})\,. }[/math]

Then

- [math]\displaystyle{ u(\mathbf{r} + \mathbf{a}_j) = \mathrm{e}^{-\mathrm{i}\mathbf{k} \cdot (\mathbf{r} + \mathbf{a}_j)} \psi(\mathbf{r}+\mathbf{a}_j) = \big( \mathrm{e}^{-\mathrm{i}\mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{r}} \mathrm{e}^{-\mathrm{i}\mathbf{k}\cdot \mathbf{a}_j} \big) \big( \mathrm{e}^{2\pi \mathrm{i} \theta_j} \psi(\mathbf{r}) \big) = \mathrm{e}^{-\mathrm{i}\mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{r}} \mathrm{e}^{-2\pi \mathrm{i} \theta_j} \mathrm{e}^{2\pi \mathrm{i} \theta_j} \psi(\mathbf{r}) = u(\mathbf{r}) }[/math].

This proves that u has the periodicity of the lattice. Since [math]\displaystyle{ \psi(\mathbf{r}) = \mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i} \mathbf{k}\cdot\mathbf{r}} u(\mathbf{r}) }[/math], that proves that the state is a Bloch wave.

2.3. Proof

Finally, we are ready for the main proof of Bloch's theorem which is as follows.

As above, let [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{T}_{n_1,n_2,n_3} \! }[/math] denote a translation operator that shifts every wave function by the amount n1a1 + n2a2 + n3a3, where ni are integers. Because the crystal has translational symmetry, this operator commutes with the Hamiltonian operator. Moreover, every such translation operator commutes with every other. Therefore, there is a simultaneous eigenbasis of the Hamiltonian operator and every possible [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{T}_{n_1,n_2,n_3} \! }[/math] operator. This basis is what we are looking for. The wavefunctions in this basis are energy eigenstates (because they are eigenstates of the Hamiltonian), and they are also Bloch waves (because they are eigenstates of the translation operators; see Lemma above).

The concept of the Bloch state was developed by Felix Bloch in 1928,[1] to describe the conduction of electrons in crystalline solids. The same underlying mathematics, however, was also discovered independently several times: by George William Hill (1877),[2] Gaston Floquet (1883),[3] and Alexander Lyapunov (1892).[4] As a result, a variety of nomenclatures are common: applied to ordinary differential equations, it is called Floquet theory (or occasionally the Lyapunov–Floquet theorem). The general form of a one-dimensional periodic potential equation is Hill's equation:[5]

-

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac {d^2y}{dt^2}+f(t) y=0, }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac {d^2y}{dt^2}+f(t) y=0, }[/math]

where f(t) is a periodic potential. Specific periodic one-dimensional equations include the Kronig–Penney model and Mathieu's equation.

Mathematically Bloch's theorem is interpreted in terms of unitary characters of a lattice group, and is applied to spectral geometry.[6][7][8]

References

- Felix Bloch (1928). "Über die Quantenmechanik der Elektronen in Kristallgittern" (in de). Zeitschrift für Physik 52 (7–8): 555–600. doi:10.1007/BF01339455. Bibcode: 1929ZPhy...52..555B. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2FBF01339455

- George William Hill (1886). "On the part of the motion of the lunar perigee which is a function of the mean motions of the sun and moon". Acta Math. 8: 1–36. doi:10.1007/BF02417081. https://zenodo.org/record/1691491. This work was initially published and distributed privately in 1877.

- Gaston Floquet (1883). "Sur les équations différentielles linéaires à coefficients périodiques". Annales Scientifiques de l'École Normale Supérieure 12: 47–88. doi:10.24033/asens.220. https://dx.doi.org/10.24033%2Fasens.220

- Alexander Mihailovich Lyapunov (1992). The General Problem of the Stability of Motion. London: Taylor and Francis. Translated by A. T. Fuller from Edouard Davaux's French translation (1907) of the original Russian dissertation (1892).

- Hill's Equation. Courier Dover. 2004. p. 11. ISBN 0-486-49565-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=ML5wm-T4RVQC&dq=%22hill's+equation%22&printsec=frontcover#PPA11,M1.

- Kuchment, P.(1982), Floquet theory for partial differential equations, RUSS MATH SURV., 37,1-60

- Katsuda, A.; Sunada, T (1987). "Homology and closed geodesics in a compact Riemann surface". Amer. J. Math. 110 (1): 145–156. doi:10.2307/2374542. https://dx.doi.org/10.2307%2F2374542

- Kotani M; Sunada T. (2000). "Albanese maps and an off diagonal long time asymptotic for the heat kernel". Comm. Math. Phys. 209 (3): 633–670. doi:10.1007/s002200050033. Bibcode: 2000CMaPh.209..633K. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs002200050033