Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Jen-Pin Chuang and Version 3 by Conner Chen.

Locally advanced colon cancer (LACC) is defined as primary stage T4 colon cancer with direct invasion of surrounding organs or extensive regional lymph node (LN) involvement. Cancer-related biomarkers are beneficial for early detection of cancer and the prediction of prognosis, survival, and treatment response. Colon cancer is a multifactorial malignant disease. Tumor size and its microscopic features, such as the level of aggressiveness; tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM) classification; and lymphatic and venous invasion, have been utilized as fundamental biomarkers for the prediction of prognosis and treatment of colon cancer.

- locally advanced colon cancer

- biomarker

- predictive

1. Prognostic Biomarkers for LACC

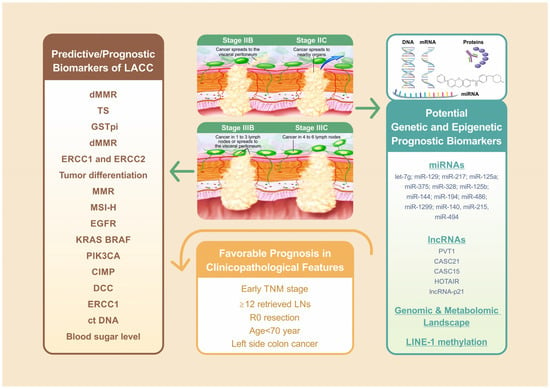

The tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM) staging system and adjuvant chemotherapy remain the foundation of prognostication in locally advanced colon cancer LACC (Figure 12) [1][9]. An observational study including 15,489 patients with stage IIB/C disease reported a median survival of 122.6 months for stage IIB/C and the retrieval of ≥12 lymph nodes (LNs) following adjuvant chemotherapy, 72.5 months for stage IIB/C and the retrieval of <12 LNs following adjuvant chemotherapy, and only 46.5 months for stage IIB/C without chemotherapy [2][54]. A Dutch study including 10,878 patients with LACC indicated that old age (≥70 year), incomplete resection margin, and nodal positivity status were significantly associated with poor survival [3][4]. The site of colon cancer development is another key prognostic factor for LACC (Figure 12) [4][5][6][7][55,56,57,58]. Differences in the embryonic origin divide the colon into left and right sides. The left side refers to the region between the splenic flexure and the upper anal canal, whereas the right side includes the cecum, ascending colon, and transverse colon. In a Taiwanese study including 1095 colorectal cancer (CRC) patients, overall survival (OS)OS and cancer-specific survival were shorter in right-sided colon cancer compared with left-sided colon cancer for all stages; these survival differences were particularly significant in those with stage III disease [4][55]. A population-based cohort study including 163,980 patients with colon cancer suggested that left-sided colon cancer was associated with longer OS in stage I, III, and IV disease but shorter OS in stage II disease in patients with left-sided colon cancer than in those with right-side colon cancer [5][56]. However, another meta-analysis including 66 studies with 1,437,846 patients reported that the longer OS of patients with left-sided colon cancer was independent of stage, race, adjuvant chemotherapy, year of study, number of participants, and quality of included studies [7][58]. A Taiwanese CRC cohort study indicated that differences in the genomic and metabolomic landscape between right-sided and left-sided CRC may be a potential biomarker [6][57].

Figure 12. Of all factors associated with LACC treatment outcome, the TNM staging system remains the foundation for LACC prognosis. For stage IIB/C, ≥12 retrieved LNs with adjuvant chemotherapy revealed favorable prognosis compared with those <12 retrieved LNs with or without adjuvant chemotherapy. The further analysis indicated that old age (≥70 year), incomplete resection margin, nodal positivity status are significantly associated with worse survival. Left side colon cancer is another independent favorable prognostic factor for LACC. Mismatch repair (MMR) and microsatellite instability (MSI) and MSI status played crucial predictive and prognostic roles in LACC patients receiving neoadjuvant or adjuvant FOLFOX or immunotherapy, and expression of ERCC1 is a significant predictive biomarker for colon cancer patients undergoing neoadjuvant or adjuvant oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy.

2. Predictive Biomarkers for LACC Undergoing Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy

For the management of LACC, neoadjuvant chemotherapy can provide better a survival benefit compared with adjuvant chemotherapy, with an acceptable side effect profile [8][31]. However, a nationwide population-based cohort study only observed this survival benefit in those with locally advanced (T4b) colon cancer but not in patients with T3 or T4a disease. These data suggest that T4b is a critical indicator of the downstaging effect following neoadjuvant chemotherapy [9][59].

2.1. Mismatch Repair Deficiency

Mismatch repair (MMR) deficient (dMMR) cells produce truncated, nonfunctional proteins or exhibit loss of proteins, which can lead to cancer. dMMR occurs in approximately 15% of sporadic CRC cases. With immunohistochemistry, tumors that demonstrate loss of an MMR protein can be classified as dMMR and those with intact MMR proteins can be classified as proficient MMR (pMMR) [10][11][60,61]. At the 2020 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, the FOxTROT Collaborative Group, which is the largest phase III trial addressing neoadjuvant FOLFOX chemotherapy with or without panitumumab for 1053 patients with radiologically staged T3-4, N0-2, and M0 colon cancer, demonstrated that neoadjuvant chemotherapy resulted in moderate or greater histological tumor regression in patients with pMMR than in those with dMMR: 23% (128/553) vs. 7% (8/115), p < 0.001, and only patients with pMMR could benefit from a decreased risk of relapse at two years [RR = 0.72 (0.52–1.00), p = 0.05] but not in dMMR tumours: [RR = 0.94 (0.43 to 2.07), p = 0.9] [12][28]. However, a retrospective study published in 2022 revealed a controversial result: among 52 patients with cT4 colon cancer, the majority of tumor regression grades in both groups were mild [dMMR vs. pMMR: 64.5% (20/31) vs. 47.6% (10/21)] and moderate [dMMR vs. pMMR: 16.1% (5/31) vs. 28.6% (6/21)]. Likewise, more than half of patients with dMMR experienced downstaging comparable to that of pMMR (64.5% vs. 47.6%). Notably, the three-year disease-free survival (DFS) and OS were 95.2% and 97.0% in patients with dMMR, respectively, compared with 76.2% and 85.7% in patients with pMMR, respectively [13][62]. MMR status plays a pivotal role in immunotherapy for colon cancer. A study evaluating the efficacy of antiprogrammed cell death 1 (PD1) among patients with advanced dMMR cancer in 12 different tumor types (including colon cancer) elucidated the benefit of immune checkpoint blockade in dMMR-MSI-H colon cancers [14][63]. In 35 patients with early-stage colon cancers who received ipilimumab with nivolumab, a pathological response was observed in 20 (100%) out of 20 patients (100%; 95% exact confidence interval [CI], 86–100%) in the dMMR group and only 4 (27%) out of 15 patients in the pMMR group [15][64]. In 2022, Chalabi et al. reported the promising downstaging effect of neoadjuvant immunotherapy in dMMR LACC (Figure 1). Among 112 patients with cT3 or N+ dMMR colon cancer (including 63% clinical T4a or T4b tumors), 95% exhibited a major pathological response, with 67% of them exhibiting a pathological complete response after receiving neoadjuvant ipilimumab plus nivolumab therapy [16][65]. Immune-checkpoint inhibitors for metastatic colon cancer (mCRC) have demonstrated favorable results for the dMMR/MSI-high (MSI-H) subgroup [17][18][66,67].

2.2. Excision Repair Cross-Complementing 1, Thymidylate Synthase, and Glutathione S-Transferase pi

In addition to MMR status, the expression of excision repair cross-complementing 1 (ERCC1) has attracted attention for its critical role in the repair of platinum-induced DNA damage. This DNA excision repair protein participates in DNA repair and DNA recombination in human cells. In a study including 70 patients with advanced CRC, the expression of ERCC1 and thymidylate synthase (TS) were investigated as potential negative prognostic factors for FOLFOX neoadjuvant chemotherapy [19][68]. Another study including 39 patients with advanced CRC indicated that those without the expression of ERCC1 or glutathione S-transferase pi but not TS were more likely to respond to FOLFOX chemotherapy [20][69].

3. Predictive Biomarkers for Patients with LACC Undergoing Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy

A growing body of evidence supports the notion that neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery is a reasonable treatment for LACC [21][22][23][37,38,39]. However, the discovery of predictive biomarkers of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for LACC is still in progress. Both ERCC1 and excision repair cross-complementing 2 (ERCC2) overexpression were associated with poor response to FOLFOX-based concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) in 14 consecutive patients with cT4b colon cancer, and irinotecan plus 5-FU/leucovorin (FOLFIRI) may be a potential second-line neoadjuvant treatment after FOLFOX-based CCRT failure [24][70]. In addition to predictive biomarkers, the prognostic indicators of survival for LACC undergoing neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy have been investigated. Yuan et al. evaluated the efficacy of a neoadjuvant regimen consisting of radiotherapy and fluoropyridine-based chemotherapy for 100 patients with unresectable LACC. This observational study suggested that low differentiation, non-R0 resection, ypT stage (ypT4a-T4b), and advanced ypTNM stage (ypIIb-IIIc) were significantly associated with poor OS and progression-free survival in univariate analysis. However, unlike rectal carcinoma, posttreatment TNM staging is a pivotal prognostic indicator of survival after preoperative CCRT [25][71]. After multivariate analysis, only differentiation remained an independent prognostic factor for OS. Differences in ypN stage, MMR status, sex, age, and nutritional status were not associated with differences in survival. Notably, patients who achieved a pathological complete response exhibited longer survival than did those who did not achieve a pathological complete response after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. However, the difference was not statistically significant; this was possibly caused by the small sample size [23][39].

4. Prognostic/Predictive Biomarkers of Postoperative Adjuvant Chemotherapy for LACC

R0 resection is crucial for curing LACC. Leijssen et al. indicated that even in curative resection, a radial margin of <1 cm and LN involvement were independent predictors of poor DFS [26][24]. Furthermore, a Dutch study reported that multivisceral resection (MVR) was independently associated with less incomplete resection but not with survival [3][4]. Likewise, adjuvant chemotherapy in the regimen of oxaliplatin and fluoropyrimidine (FOLFOX or CAPOX) prevents recurrence by eradicating minimal residual disease and has been approved as a standard treatment for stage III colon cancer [27][21]. The identification of numerous molecular biomarkers for postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy can improve outcomes by allowing the personalization of treatment strategies for patients with LACC.

4.1. MMR

The prognostic effect of MMR status on postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy for LACC remains controversial. In a study including 324 patients who underwent radical surgical resection for high-risk stage II or III colon cancer between 2005 and 2008, oxaliplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy was primarily beneficial for patients with pMMR but may not for patients with tumors that exhibit dMMR [28][72]. By contrast, a pooled analysis of two randomized clinical trials (NCCTG N0147 and PETACC8), which included 2501 patients with stage III colon cancer, reported that the dMMR phenotype was a favorable prognostic factor for patients with stage III colon cancer receiving FOLFOX adjuvant chemotherapy, and DFS was significantly longer for patients with the dMMR phenotype than for patients with the pMMR phenotype [29][50]. Notably, two trials are currently ongoing to determine the efficacy of adjuvant anti-PDL1 monoclonal antibodies in patients with stage III dMMR colon cancer (ATOMIC and POLEM) [30][31][73,74].

4.2. MSI-High

MSI linked to mutations in MMR genes refers to genetic hypermutability (predisposition to mutations) that results in variations in MS sequence length or base composition. This is an alteration often caused by dMMR. The MS status of a tumor may be classified as stable (MSS), low instability (MSI-L), or high instability (MSI-H). In general, dMMR is equivalent to MSI-H. [32][75]. Tumors with pMMR–MSI-L signature have a lower tumor mutation burden (<8.24 mutations per 106 DNA bases), and those with dMMR–MSI-H signature have a high mutation burden (>12 mutations per 106 DNA bases) [33][76]. In sporadic colon cancer, MSI is more common in stage II (approximately 20%) and III (12%) tumors than in stage IV tumors (4%) [34][77]. However, for patients with stage III colon cancer receiving FOLFOX adjuvant chemotherapy, the prognostic role of MSI versus MSS tumors has also been reported. Compared with patients with MSI-L/MSS colon cancer, those with MSI-H colon cancer exhibited no significant differences in five-year DFS and OS [35][36][12,18], and the MSI/dMMR phenotype was associated with better survival after relapse than did the MSS/pMMR phenotype in patients with stage III colon cancer after adjuvant chemotherapy [37][49]. In patients receiving 5-FU treatment, MSI-H was a more reliable favorable prognostic biomarker for relapse-free survival and OS in stage II colon cancer but not in stage III colon cancer [38][19]. This finding is consistent with those of previous studies [39][40][41][48,78,79].

4.3. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Expression

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is a 170-KDa transmembrane tyrosine kinase. The EGFR/RAS/RAF/MEK/MAPK pathway plays a crucial role in the occurrence, invasion, and metastasis of colorectal cancer [42][43][44][80,81,82]. Huang et al. demonstrated that in 144 patients with stage III colon cancer who underwent radical resection and adjuvant chemotherapy with the FOLFOX regimen, positive EGFR expression and an abnormal postoperative serum carcinoembryonic antigen level were significantly associated with postoperative relapse. Positive EGFR expression was reported to be a significant independent negative prognostic factor for DFS and OS [45][17]. Moreover, EGFR expression was a prognostic factor for patients with stage III CRC receiving metronomic maintenance therapy [46][83].

4.4. KRAS and BRAF

KRAS mutation occurs in 15–35% of localized colon cancer cases, and BRAF mutation is a relatively rare event that occurs in 8–10% of patients with localized colon cancer. Both appear to be associated with decreased DFS, survival after recurrence (SAR), and OS [37][47][48][49][49,84,85,86]. In a pooled analysis including patients with stage III colon cancer receiving adjuvant FOLFOX, BRAF or KRAS mutations were significantly associated with shorter time to recurrence (TTR), SAR, and OS in those with MSS but not in those with MSI [37][49]. Among patients with recurrent stage III colon cancer after oxaliplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy, mutations in BRAF were significantly associated with poor SAR [49][50][86,87]. Poor SAR for tumors with BRAF or KRAS mutations was more strongly associated with distal cancers [49][86].

4.5. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-Bisphosphate 3-Kinase Catalytic Subunit Alpha

Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA) encodes the p110α catalytic subunit of PI3 kinase. PIK3CA mutations are present in approximately 17% of colon cancers and result in the constitutive activation of the kinase and downstream AKT pathway [51][88]. Patients with PIK3CA-mutated CRC appear to have better survival after receiving aspirin in addition to chemotherapy [52][89]. In the VICTOR trial, which included 896 participants after primary CRC resection, rofecoxib (COX-2–selective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) failed to provide effective outcomes in those with stage II–III tumors with PIK3CA mutations compared to those with wild-type PIK3CA. However, in patients with tumors with PIK3CA mutations, the recurrence rate was lower in the regular aspirin use subgroup. This prospective study further supported the benefit of adjuvant aspirin in patients with PIK3CA mutations [51][88]. A double-blind randomized phase III trial (PRODIGE 50-ASPIK) evaluating aspirin (100 mg/d during 3 years or until recurrence) versus placebo in stage III or high-risk stage II colon cancer with a PIK3CA mutation after surgical resection is ongoing [53][90].

4.6. CpG Island Methylator Phenotype

The CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) phenotype refers to the hypermethylation state of CpG islands localized in gene enhancer regions and occurs in approximately 18% of colon cancer [54][91]. In stage III colon cancer, patients with CIMP-positive tumors exhibited poorer OS than did those with CIMP-negative tumors [54][55][91,92]. CIMP-positive, MMR-intact colon tumors appeared to benefit most from irinotecan-based adjuvant therapy for stage III colon cancer [55][92]. However, a large cohort study including 1867 patients with stage III colon cancer treated with oxaliplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy reported that CIMP positivity was associated with shorter OS and SAR but not DFS [54][91].

4.7. Deleted in Colorectal Cancer Protein

The deleted in CRC (DCC) protein is encoded by DCC (chromosome 18q21.2) and is a prognostic factor for patients with stage II and III CRC [56][93]. Gall et al. reported that for patients with stage II and III CRC, the DCC-positive subgroup responded well to adjuvant chemotherapy. By contrast, in the DCC-negative subgroup, no significant difference between chemotherapy and OS or DFS was reported. Therefore, DCC is likely to be a reliable predictor of response to adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with CRC [57][94].

4.8. ERCC1

ERCC1 is a potential predictive biomarker for the efficacy of oxaliplatin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy or preoperative CCRT in colon cancer treatment [19][20][24][68,69,70]. ERCC1 overexpression is a key predictor of early failure of FOLFOX-4 adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage III CRC. Among analyzed patients, ERCC2 and XRCC1 expression exhibited no predictive role [58][95].

4.9. Circulating Tumor Cells or Circulating Tumor DNA

The persistent presence of postchemotherapeutic circulating tumor cells (CTCs) is a potential powerful surrogate marker for determining clinical outcomes in patients with stage III colon cancer receiving adjuvant mFOLFOX chemotherapy [59][96]. Moreover, CTCs can be used in real-time tumor biopsy for designing individually tailored therapy against CRC [60][97]. Likewise, postsurgical circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis is a powerful tool to detect minimal residual disease and is a promising prognostic marker in CRC treatment [61][98]. Tie et al. demonstrated that in 96 patients with stage III colon cancer, the estimated three-year RFI was 30% when ctDNA was detectable after adjuvant chemotherapy and 77% when ctDNA was undetectable (HR, 6.8; 95% CI, 11.0–157.0; p < 0.001) [62][51].

4.10. Blood Sugar Level

3.4.10. Blood Sugar Level

Metabolic syndrome, particularly diabetes, is a major etiological risk factor for the development and progression of CRC [63][64][65][99,100,101]. Increased blood sugar levels may drive cancer cell proliferation and increase CRC resistance to chemotherapy [55][66][67][52,92,102]. Yang et al. demonstrated that in 157 patients with stage III CRC (including 107 colon cancer cases) receiving adjuvant FOLFOX6 chemotherapy and having a fasting blood sugar level of ≥126 mg/dL but not a history of diabetes mellitus significantly enhanced oxaliplatin chemoresistance (Table 1). Hyperglycemia can affect clinical outcomes in patients with stage III CRC receiving adjuvant chemotherapy, and the mechanism of oxaliplatin resistance may be related to the increased phosphorylation of SMAD3 and MYC and upregulation of EHMT2 expression [66][52].

Table 1.

Predictive and prognostic biomarkers for LACC in different treatment phases.

| LACC Treatment Phases | Biomarkers (Predictive/Prognostic) |

Prediction Value (Favorable/Worse) |

References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinicopathological features | TNM staging (Prognostic) | Favorable (early TNM) | [1][3][4,9] |

| ≥12 retrieved LNs (Prognostic) | Favorable | [2][54] | |

| R0 resection (Prognostic) | Favorable | [3][26][4,24] | |

| Age ≥ 70 year (Prognostic) | Worse | [3][4] | |

| Sidedness of colon cancer (Prognostic) | Favorable (Left side colon cancer) |

[4][55] | |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy |

dMMR (Predictive/Prognostic) | Worse | [12][13][28,62] |

| ERCC1 (Predictive/Prognostic), TS (Prognostic), GSTpi (Predictive) |

Worse | [19][20][68,69] | |

| Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy |

dMMR (Predictive) | Favorable | [16][65] |

| Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy |

ERCC1 and ERCC2 (Predictive) | Worse | [24][70] |

| Tumor differentiation (Prognostic) |

Worse (Low differentiation) |

[23][39] | |

| Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy | MMR (Prognostic) | Controversial | [28][29][30][31][49][50][50,72,73,74,86,87] |

| MSI-H (Prognostic) | Favorable | [37][38][39][40][41][50][19,48,49,78,79,87] | |

| EGFR (Prognostic) | Worse | [45][17[46],83] | |

| KRAS and BRAF(Prognostic) | Worse | [37][49][50][49,86,87] | |

| PIK3CA (Prognostic) 1 | Favorable | [53][90] | |

| CIMP (Prognostic) | Worse | [54][55][91,92] | |

| DCC (Prognostic) | Favorable | [56][57][93,94] | |

| ERCC1 (Prognostic) | Worse | [58][95] | |

| ct DNA (Prognostic) | Worse | [59][60][61][62][51,96,97,98] | |

| Blood sugar level (Prognostic) | Worse (Fasting blood sugar ≥ 126 mg/dL) |

[66][52] |