Epigenetics of anxiety and stress-related disorders is the field studying the relationship between epigenetic modifications of genes and anxiety and stress-related disorders, including mental health disorders such as generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and more. Epigenetic modifications play a role in the development and heritability of these disorders and related symptoms. For example, regulation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis by glucocorticoids plays a major role in stress response and is known to be epigenetically regulated. As of 2015 most work has been done in animal models in laboratories, and little work has been done in humans; the work is not yet applicable to clinical psychiatry.

- mental health disorders

- stress-related disorders

- animal models

1. Epigenetic Writers, Erasers, and Readers

Epigenetic changes are performed by enzymes known as writers, which can add epigenetic modifications, erasers, which erase epigenetic modifications, and readers, which can recognize epigenetic modifications and cause a downstream effect. Stress-induced modifications of these writers, erasers, and readers result in important epigenetic modifications such as DNA methylation and acetylation.

1.1. DNA Methylation

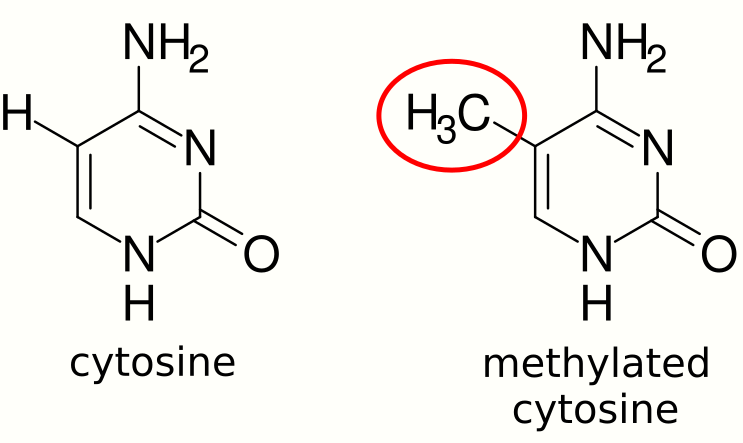

DNA methylation is a type of epigenetic modification in which methyl groups are added to cytosines of DNA. DNA methylation is an important regulator of gene expression and is usually associated with gene repression.

MeCP2

Laboratory studies have found that early life stress in rodents can cause phosphorylation of methyl CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2), a protein that preferentially binds CpGs and is most often associated with suppression of gene expression. Stress-dependent phosphorylation of MeCP2 causes MeCP2 to dissociate from the promoter region of a gene called arginine vasopressin (avp), causing avp to become demethylated and upregulated. This may be significant because arginine vasopressin is known to regulate mood and cognitive behavior. Additionally, arginine vasopressin upregulates corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which is a hormone important for stress response. Thus, stress-induced upregulation of avp due to demethylation might alter mood, behavior, and stress responses. Demethylation of this locus can be explained by reduced binding of DNA methyl transferases (DNMT), an enzyme that adds methyl groups to DNA, to this locus.[1]

MeCP2 is known to have interactions with several other enzymes that modify chromatin (for example, HDAC-containing complexes and co-repressors) and in turn regulate activity of genes that modulate stress response either by increasing or decreasing stress tolerance. For example, epigenetic upregulation of genes that increase stress response may cause decreased stress tolerance in an organism. These interactions are dependent on the phosphorylation status of MeCP2, which as previously mentioned, can be altered by stress.[1][2]

DNMT1

DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) belongs to a family of proteins known as DNA methyltransferases, which are enzymes that add methyl groups to DNA. DNMT1 is specifically involved in maintaining DNA methylation; hence it is also known as the maintenance methylase DNMT1. DNMT1 aids in regulation of gene expression by methylating promoter regions of genes, causing transcriptional repression of these genes.

DNMT1 is transcriptionally repressed under stress-mimicking exposure both in vitro and in vivo using a mouse model. Accordingly, transcriptional repression of DNMT1 in response to long-term stress-mimicking exposure causes decreased DNA methylation, which is a marker of gene activation. In particular, there is decreased methylation of a gene called fkbp5, which plays a role in stress response as a glucocorticoid-responsive gene. Thus, chronic stress may cause demethylation and hyperactivation of a stress-related gene, causing increased stress response.[1][3]

Additionally, DNMT1 gene locus has increased methylation in individuals who were exposed to trauma and developed post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Increased methylation of DNMT1 did not occur in trauma-exposed individuals who did not develop PTSD. This may indicate an epigenetic phenotype that can differentiate PTSD-susceptible and PTSD-resilient individuals after exposure to trauma.[1][4]

Transcription factors

Transcription factors are proteins that bind DNA and modulate the transcription of genes into RNA such as mRNA, tRNA, rRNA, and more; thus they are essential components of gene activation. Stress and trauma can affect expression of transcription factors, which in turn alter DNA methylation patterns.

For example, transcription factor nerve growth-induced protein A (NGFI-A, also called NAB1) is up-regulated in response to high maternal care in rodents, and down-regulated in response to low maternal care (a form of early life stress). Decreased NGFI-A due to low maternal care increases methylation of a glucocorticoid receptor promoter in rats. Glucocorticoid is known to play a role in downregulating stress response; therefore, downregulation of glucocorticoid receptor by methylation causes increased sensitivity to stress.[1][5][6]

1.2. Histone Acetylation

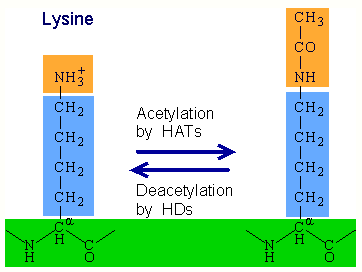

Histone acetylation is a type of epigenetic modification in which acetyl groups are added to lysine on histone tails. Histone acetylation, performed by enzymes known as histone acetyltransferases (HATs), removes the positive charge from lysine and results in gene activation by weakening the histone's interaction with negatively-charged DNA. In contrast, histone deacetylation performed by histone deacetylases (HDACs) results in gene deactivation.

HDAC

Transcriptional activity and expression of HDACs is altered in response to early life stress.[1][7][8] For animals exposed to early life stress, HDAC expression tends to be lower when they are young and higher when they are older. This suggests an age-dependent effect of early life stress on HDAC expression. These HDACs may result in deacetylation and thus activation of genes that upregulate stress response and decrease stress tolerance.[1][9]

2. Transgenerational Epigenetic Influences

Genome-wide association studies have shown that psychiatric disorders are partly heritable; however, heritability cannot be fully explained by classical Mendelian genetics. Epigenetics has been postulated to play a role. This is because there is strong evidence of transgenerational epigenetic effects in general. For example, one study found transmission of DNA methylation patterns from fathers to offspring during spermatogenesis. More specifically to mental illnesses, several studies have shown that traits of psychiatric illnesses (such as traits of PTSD and other anxiety disorders) can be transmitted epigenetically. Parental exposure to various stimuli, both positive and negative, can cause these transgenerational epigenetic and behavioral effects.[10]

2.1. Parental Exposure to Trauma and Stress

Trauma and stress experienced by a parent can cause epigenetic changes to its offspring. This has been observed both in population and experimental studies.[10]

Holocaust

An epidemiological study investigating behavioral, physiological, and molecular changes in the children of Holocaust survivors found epigenetic modifications of a glucocorticoid receptor gene, Nr3c1. This is significant because glucocorticoid is a regulator of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) and is known to affect stress response. These stress-related epigenetic changes were accompanied by other characteristics that indicated higher stress and anxiety in these offspring, including increased symptoms of PTSD, greater risk of anxiety, and higher levels of the stress hormone cortisol.[10][11][12][13]

Experimental evidence

The effect of parental exposure to stress has been tested experimentally as well. For example, male mice who were put under early life stress through poor maternal care—a scenario analogous to human childhood trauma—passed on epigenetic changes that resulted in behavioral changes in offspring. Offspring experienced altered DNA methylation of stress-response genes such as CB1 and CRF2 in the cortex, as well as epigenetic alterations in transcriptional regulation gene MeCP2. Offspring were also more sensitive to stress, which is in accordance with the altered epigenetic profile. These changes persisted for up to three generations.[10][14]

In another example, male mice were socially isolated as a form of stress. Offspring of these mice had increased anxiety in response to stressful conditions, increased stress hormone levels, dysregulation of the HPA axis which plays a key role in stress response, and several other characteristics that indicated increased sensitivity to stress.[10][14]

Inheritance of small-noncoding RNA

Studies have found that early life stress induced through poor maternal care alters sperm epigenome in male mice. In particular, expression patterns of small-noncoding RNAs (sncRNAs) are altered in the sperm, as well as in stress-related regions of the brain.[15][16][17] Offspring of these mice exhibited the same sncRNA expression changes in the brain, but not in the sperm. These changes were coupled with behavioral changes in the offspring that were comparable to behavior of the stressed fathers, especially in terms of stress response. Additionally, when the sncRNAs in the fathers' sperm were isolated and injected into fertilized eggs, the resulting offspring inherited the stress behavior of the father. This suggests that stress-induced modifications of sncRNAs in sperm can cause inheritance of stress phenotype independent of the father's DNA.[15][16]

2.2. Parental Exposure to Positive Stimulation

Exercise

Just as parental stress can alter epigenetics of offspring, parental exposure to positive environmental factors cause epigenetic modifications as well. For example, male mice that participated in voluntary physical exercise resulted in offspring that had reduced fear memory and anxiety-like behavior in response to stress. This behavioral change likely occurred due to expressions of small non-coding RNAs that were altered in sperm cells of the fathers.[10][18]

Stress effect reversal

Additionally, exposing fathers to enriching environments can reverse the effect of early life stress on their offspring. When early life stress is followed by environmental enrichment, anxiety-like behavior in offspring is prevented.[10][19] Similar studies have been conducted in humans and suggest that DNA methylation plays a role.[20]

3. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a stress-related mental health disorder that emerges in response to traumatic or highly stressful experiences. It is believed that PTSD develops as a result of an interaction between these traumatic experiences and genetic factors. Evidence suggests epigenetics is a key element in this.[21]

3.1. DNA Methylation

Through a number of human studies, PTSD is known to affect DNA methylation of cytosine residues in several genes involved in stress response, neurotransmitter activity, and more.[21]

| Genetic Loci | Finding(s) |

|---|---|

| SLC6A4 | Following trauma exposure, low methylation levels of SLC6A4 increases risk of PTSD; high methylation levels decreases risk of PTSD[22] |

| MAN2C1 | Higher MAN2C1 methylation is correlated to greater risk of PTSD in individuals exposed to traumatic events[23] |

| TPR, CLEC9A, APC5, ANXA2, TLR8 | PTSD is associated with increased global methylation of these genes[24] |

| ADCYAP1R1 | Higher methylation is associated with PTSD symptoms in individuals exposed to trauma[25] |

| LINE-1, Alu | Higher methylation of these loci is observed in postdeployed veterans who developed PTSD compared to those who do not develop PTSD[26] |

| SLC6A3 | High SLC6A3 promoter methylation, combined with a nine-repeat allele of SLC6A3, is correlated to higher PTSD risk[27] |

| IGF2, H19, IL8, IL16, IL18 | Higher methylation of IL18 but lower methylation of H19 and IL18 is associated with deployed veterans who developed PTSD<[28] |

| NR3C1 | Lower methylation levels of NR3C1 1B and 1C promoters is associated with PTSD;[29]

Fathers with PTSD have offspring with higher NR3C1 1F promoter methylation;[13] Lower levels of NR3C1 1F promoter methylation is associated with PTSD in combat veterans;[30] Higher levels of NR3C1 methylation in male (but not female) Rwandan genocide survivors is associated with decreased PTSD risk[31] |

3.2. Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis

The hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis plays a key role in stress response. Based on several findings, the HPA axis appears to be dysregulated in PTSD. A common pathway dysregulated in HPA axis involves a hormone known as glucocorticoid and its receptor, which aid in stress tolerance by downregulating stress response. Dysregulation of glucocorticoid and/or glucocorticoid receptor can disrupt stress tolerance and increase risk of stress-related disorders such as PTSD. Epigenetic modifications play a role in this dysregulation, and these modifications are likely caused by the traumatic/stressful experience that triggered PTSD.[21]

NR3C1

Nr3c1 is a gene that encodes a glucocorticoid receptor (GR) and contains many GR response elements. Early life stress increases methylation of the 1F promoter in this gene (or the 17 promoter analog in rodents). Because of its role in stress response and its link to early life stress, this gene has been of particular interest in the context of PTSD and has been studied in PTSD of both combat veterans and civilians.[21]

In studies involving combat veterans, those who developed PTSD had lowered methylation of the Nr3c1 1F promoter compared to those who did not develop PTSD. Additionally, veterans who developed PTSD and had higher Nr3c1 promoter methylation responded better to long-term psychotherapy compared to veterans with PTSD who had lower methylation. These findings were recapitulated in studies involving civilians with PTSD.[21][32] In civilians, PTSD is linked to lower methylation levels in the T-cells of exons 1B and 1C of Nr3c1, as well as higher GR expression. Thus, it seems that PTSD causes lowered methylation levels of GR loci and increased GR expression.[21][29]

Although these results of decreased methylation and hyperactivation of GR conflict with the effect of early life stress at the same loci, these results match previous findings that distinguish HPA activity in early life stress versus PTSD. For example, cortisol levels of HPA in response to early life stress is hyperactive, whereas it is hypoactive in PTSD. Thus, the timing of trauma and stress—whether early or later in life—can cause differing effects on HPA and GR.[29]

FKBP5

Fkbp5 encodes a GR-responsive protein known as Fk506 binding protein 51 (FKBP5). FKBP5 is induced by GR activation and functions in negative feedback by binding GR and reducing GR signaling.[21][33][34][35] There is particular interest in this gene because some FKBP5 alleles have been correlated with increased risk of PTSD and development of PTSD symptoms—especially in PTSD caused by early life adversity. Therefore, FKBP5 likely plays an important role in PTSD.[21][36][37][38]

As mentioned previously, certain FKBP5 alleles are correlated to increase PTSD risk, especially due to early life trauma. It is now known that epigenetic regulation of these alleles is also an important factor. For example, CpG sites in intron 7 of FKBP5 are demethylated after exposure to childhood trauma, but not adult trauma.[21][39] Additionally, methylation of FKBP5 is alters in response to PTSD treatment; thus methylation levels of FKBP5 might correspond to PTSD disease progression and recovery.[13][21]

ADCYAP1 and ADCYAP1R1

Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (ADCYAP1) and its receptor (ADCYAP1R1) are stress responsive genes that play a role in modulating stress, among many other functions. Additionally, high levels of ADCYAP1 in peripheral blood is correlated to PTSD diagnosis in females who have experienced trauma, thus making ADCYAP1 a gene of interest in the context of PTSD.[21]

Epigenetic regulation of these loci in relation to PTSD still require further investigation, but one study has found that high methylation levels of CpG islands in ADCYAP1R1 can predict PTSD symptoms in both males and females.[21][25]

3.3. Immune Dysregulation

PTSD is often linked with immune dysregulation. This is because trauma exposure can disrupt the HPA axis, thus altering peripheral immune function.

Epigenetic modifications have been observed in immune-related genes of individuals with PTSD. For example, deployed military members who developed PTSD have higher methylation in immune-related gene interleukin-18 (IL-18).[21][28] This has interested scientists because high levels of IL-18 increase cardiovascular disease risk, and individuals with PTSD have elevated cardiovascular disease risk. Thus, stress-induced immune dysregulation via methylation of IL-18 may play a role in cardiovascular disease in individuals with PTSD.[21][24][40]

Additionally, an epigenome-wide study found that individuals with PTSD have altered levels of methylation in the following immune-related genes: TPR, CLEC9A, APC5, ANXA2, TLR8, IL-4, and IL-2. This again shows that immune function in PTSD is disrupted, especially by epigenetic changes that are likely stress-induced.[21][24]

4. Alcohol Use Disorder

Alcohol dependence and stress interact in many ways. For example, stress-related disorders such as anxiety and PTSD are known to increase risk of alcohol use disorder (AUD), and they are often co-morbid. This may in part be due to the fact that alcohol can alleviate some symptoms of these disorders, thus promoting dependence on alcohol. Conversely, early exposure to alcohol can increase vulnerability to stress and stress-related disorders. Moreover, alcohol dependence and stress are known to follow similar neuronal pathways, and these pathways are often dysregulated by similar epigenetic modifications.[41]

4.1. Histone Acetylation

HDAC

Histone acetylation is dysregulated by alcohol exposure and dependence, often through dysregulated expression and activity of HDACs, which modulate histone acetylation by removing acetyl groups from lysines of histone tails. For example, HDAC expression is upregulated in chronic alcohol use models.[41] Monocyte-derived dendritic cells of alcohol users have increased HDAC gene expression compared to non-users.[42] These results are also supported by in vivo rat studies, which show that HDAC expression is higher in alcohol-dependent mice that in non-dependent mice. Furthermore, knockout of HDAC2 in mice helps lower alcohol dependence behaviors.[43] The same pattern of HDAC expression is seen in alcohol withdrawal, but acute alcohol exposure has the opposite effect; in vivo, HDAC expression and histone acetylation markers are decreased in the amygdala.[43]

Dysregulation of HDACs is significant because it can cause upregulation or downregulation of genes that have important downstream effects both in alcohol dependence and anxiety-like behaviors, and the interaction between the two. A key example is BDNF (see "BDNF" below).

BDNF

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is a key protein that is dysregulated by HDAC dysregulation. BDNF is a protein that regulates the structure and function of neuronal synapses. It plays an important role in neuronal activation, synaptic plasticity, and dendritic morphology—all of which are factors that may affect cognitive function. Dysregulation of BDNF is seen both in stress-related disorders and alcoholism; thus BDNF is likely an important molecule in the interaction between stress and alcoholism.[41][44]

For example, BDNF is dysregulated by acute ethanol exposure. Acute ethanol exposure causes phosphorylation of CREB, which can cause increased histone acetylation at BDNF loci. Histone acetylation upregulates BDNF, in turn upregulating a downstream BDNF target called activity-regulated cytoskeleton associated protein (Arc), which is a protein responsible for dendritic spine structure and formation. This is significant because activation of Arc can be associated with anxiolytic (anxiety-reducing) effects. Therefore, ethanol consumption can cause epigenetic changes that alleviate stress and anxiety, thereby creating a pattern of stress-induced alcohol dependence.[41][44][45]

Alcohol dependence is exacerbated by ethanol withdrawal. This is because ethanol withdrawal has the opposite effect of ethanol exposure; it causes lowered CREB phosphorylation, lowered acetylation, downregulation of BDNF, and increase in anxiety. Consequently, ethanol withdrawal reinforces desire for anxiolytic effects of ethanol exposure. Moreover, it is proposed that chronic ethanol exposure results in upregulation of HDAC activity, causing anxiety-like effects that can no longer be alleviated by acute ethanol exposure.[41][43][44]

References

- "Epigenetics of Stress-Related Psychiatric Disorders and Gene × Environment Interactions". Neuron 86 (6): 1343–57. June 2015. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.05.036. PMID 26087162. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.neuron.2015.05.036

- "MeCP2 post-translational modifications: a mechanism to control its involvement in synaptic plasticity and homeostasis?". Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 8: 236. 2014. doi:10.3389/fncel.2014.00236. PMID 25165434. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4131190

- "A measure of glucocorticoid load provided by DNA methylation of Fkbp5 in mice". Psychopharmacology 218 (1): 303–12. November 2011. doi:10.1007/s00213-011-2307-3. PMID 21509501. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3918452

- "Longitudinal epigenetic variation of DNA methyltransferase genes is associated with vulnerability to post-traumatic stress disorder". Psychological Medicine 44 (15): 3165–79. November 2014. doi:10.1017/S0033291714000968. PMID 25065861. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4530981

- "Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior". Nature Neuroscience 7 (8): 847–54. August 2004. doi:10.1038/nn1276. PMID 15220929. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fnn1276

- "Epigenetic mechanisms for the early environmental regulation of hippocampal glucocorticoid receptor gene expression in rodents and humans". Neuropsychopharmacology 38 (1): 111–23. January 2013. doi:10.1038/npp.2012.149. PMID 22968814. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3521971

- "Early life stress triggers sustained changes in histone deacetylase expression and histone H4 modifications that alter responsiveness to adolescent antidepressant treatment". Neurobiology of Disease 45 (1): 488–98. January 2012. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2011.09.005. PMID 21964251. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3225638

- "Vulnerability to opiate intake in maternally deprived rats: implication of MeCP2 and of histone acetylation". Addiction Biology 20 (1): 120–31. January 2015. doi:10.1111/adb.12084. PMID 23980619. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fadb.12084

- "Early stress evokes temporally distinct consequences on the hippocampal transcriptome, anxiety and cognitive behaviour". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 17 (2): 289–301. February 2014. doi:10.1017/S1461145713001004. PMID 24025219. https://dx.doi.org/10.1017%2FS1461145713001004

- "Transgenerational epigenetic influences of paternal environmental exposures on brain function and predisposition to psychiatric disorders". Molecular Psychiatry 24 (4): 536–548. March 2018. doi:10.1038/s41380-018-0039-z. PMID 29520039. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fs41380-018-0039-z

- "Relationship of parental trauma exposure and PTSD to PTSD, depressive and anxiety disorders in offspring". Journal of Psychiatric Research 35 (5): 261–70. 2001. doi:10.1016/S0022-3956(01)00032-2. PMID 11591428. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS0022-3956%2801%2900032-2

- Transgenerational transmission of cortisol and PTSD risk. 167. 2008. 121–35. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(07)67009-5. ISBN 9780444531407. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS0079-6123%2807%2967009-5

- "Influences of maternal and paternal PTSD on epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor gene in Holocaust survivor offspring". The American Journal of Psychiatry 171 (8): 872–880. August 2014. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13121571. PMID 24832930. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4127390

- "Epigenetic transmission of the impact of early stress across generations". Biological Psychiatry 68 (5): 408–15. September 2010. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.05.036. PMID 20673872. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.biopsych.2010.05.036

- "Transgenerational Inheritance of Paternal Neurobehavioral Phenotypes: Stress, Addiction, Ageing and Metabolism". Molecular Neurobiology 53 (9): 6367–6376. November 2016. doi:10.1007/s12035-015-9526-2. PMID 26572641. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs12035-015-9526-2

- "Implication of sperm RNAs in transgenerational inheritance of the effects of early trauma in mice". Nature Neuroscience 17 (5): 667–9. May 2014. doi:10.1038/nn.3695. PMID 24728267. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4333222

- "Father-son chats: inheriting stress through sperm RNA". Cell Metabolism 19 (6): 894–5. June 2014. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2014.05.015. PMID 24896534. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4131544

- "Exercise alters mouse sperm small noncoding RNAs and induces a transgenerational modification of male offspring conditioned fear and anxiety". Translational Psychiatry 7 (5): e1114. May 2017. doi:10.1038/tp.2017.82. PMID 28463242. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5534950

- "Potential of Environmental Enrichment to Prevent Transgenerational Effects of Paternal Trauma". Neuropsychopharmacology 41 (11): 2749–58. October 2016. doi:10.1038/npp.2016.87. PMID 27277118. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5026744

- "DNA methylation, early life environment, and health outcomes". Pediatric Research 79 (1–2): 212–9. January 2016. doi:10.1038/pr.2015.193. PMID 26466079. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4798238

- "Epigenetics of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Current Evidence, Challenges, and Future Directions". Biological Psychiatry 78 (5): 327–35. September 2015. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.04.003. PMID 25979620. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.biopsych.2015.04.003

- "SLC6A4 methylation modifies the effect of the number of traumatic events on risk for posttraumatic stress disorder". Depression and Anxiety 28 (8): 639–47. August 2011. doi:10.1002/da.20825. PMID 21608084. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3145829

- "Gene expression and methylation signatures of MAN2C1 are associated with PTSD". Disease Markers 30 (2–3): 111–21. 2011. doi:10.1155/2011/513659. PMID 21508515. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3188659

- "Differential immune system DNA methylation and cytokine regulation in post-traumatic stress disorder". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part B, Neuropsychiatric Genetics 156B (6): 700–8. September 2011. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.31212. PMID 21714072. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3292872

- "Post-traumatic stress disorder is associated with PACAP and the PAC1 receptor". Nature 470 (7335): 492–7. February 2011. doi:10.1038/nature09856. PMID 21350482. Bibcode: 2011Natur.470..492R. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3046811

- "DNA methylation in repetitive elements and post-traumatic stress disorder: a case-control study of US military service members". Epigenomics 4 (1): 29–40. February 2012. doi:10.2217/epi.11.116. PMID 22332656. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3809831

- "Molecular variation at the SLC6A3 locus predicts lifetime risk of PTSD in the Detroit Neighborhood Health Study". PLOS ONE 7 (6): e39184. 2012. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039184. PMID 22745713. Bibcode: 2012PLoSO...739184C. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3383758

- "PTSD and DNA Methylation in Select Immune Function Gene Promoter Regions: A Repeated Measures Case-Control Study of U.S. Military Service Members". Frontiers in Psychiatry 4: 56. 2013. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00056. PMID 23805108. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3690381

- "Epigenetic modulation of glucocorticoid receptors in posttraumatic stress disorder". Translational Psychiatry 4 (3): e368. March 2014. doi:10.1038/tp.2014.3. PMID 24594779. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3966043

- "Lower methylation of glucocorticoid receptor gene promoter 1F in peripheral blood of veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder". Biological Psychiatry 77 (4): 356–64. February 2015. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.02.006. PMID 24661442. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.biopsych.2014.02.006

- "Epigenetic modification of the glucocorticoid receptor gene is linked to traumatic memory and post-traumatic stress disorder risk in genocide survivors". The Journal of Neuroscience 34 (31): 10274–84. July 2014. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1526-14.2014. PMID 25080589. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=6608273

- "Epigenetic Biomarkers as Predictors and Correlates of Symptom Improvement Following Psychotherapy in Combat Veterans with PTSD". Frontiers in Psychiatry 4: 118. 2013. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00118. PMID 24098286. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3784793

- "Gene-environment interactions at the FKBP5 locus: sensitive periods, mechanisms and pleiotropism". Genes, Brain, and Behavior 13 (1): 25–37. January 2014. doi:10.1111/gbb.12104. PMID 24219237. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fgbb.12104

- "FK506-binding protein 51 regulates nuclear transport of the glucocorticoid receptor beta and glucocorticoid responsiveness". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 49 (3): 1037–47. March 2008. doi:10.1167/iovs.07-1279. PMID 18326728. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2442563

- "FK506-binding proteins 51 and 52 differentially regulate dynein interaction and nuclear translocation of the glucocorticoid receptor in mammalian cells". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 280 (6): 4609–16. February 2005. doi:10.1074/jbc.M407498200. PMID 15591061. https://dx.doi.org/10.1074%2Fjbc.M407498200

- "Interaction of FKBP5 with childhood adversity on risk for post-traumatic stress disorder". Neuropsychopharmacology 35 (8): 1684–92. July 2010. doi:10.1038/npp.2010.37. PMID 20393453. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2946626

- "Association of FKBP5 polymorphisms and childhood abuse with risk of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in adults". JAMA 299 (11): 1291–305. March 2008. doi:10.1001/jama.299.11.1291. PMID 18349090. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2441757

- "Higher FKBP5, COMT, CHRNA5, and CRHR1 allele burdens are associated with PTSD and interact with trauma exposure: implications for neuropsychiatric research and treatment". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 8: 131–9. 2012. doi:10.2147/NDT.S29508. PMID 22536069. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3333786

- "Allele-specific FKBP5 DNA demethylation mediates gene-childhood trauma interactions". Nature Neuroscience 16 (1): 33–41. January 2013. doi:10.1038/nn.3275. PMID 23201972. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4136922

- "Epigenetic and immune function profiles associated with posttraumatic stress disorder". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107 (20): 9470–5. May 2010. doi:10.1073/pnas.0910794107. PMID 20439746. Bibcode: 2010PNAS..107.9470U. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2889041

- "Epigenetic mechanisms of alcoholism and stress-related disorders". Alcohol 60: 7–18. May 2017. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2017.01.001. PMID 28477725. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5464725

- "Profile of Class I Histone Deacetylases (HDAC) by Human Dendritic Cells after Alcohol Consumption and In Vitro Alcohol Treatment and Their Implication in Oxidative Stress: Role of HDAC Inhibitors Trichostatin A and Mocetinostat". PLOS ONE 11 (6): e0156421. 2016. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0156421. PMID 27249803. Bibcode: 2016PLoSO..1156421A. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4889108

- "Aberrant histone deacetylase2-mediated histone modifications and synaptic plasticity in the amygdala predisposes to anxiety and alcoholism". Biological Psychiatry 73 (8): 763–73. April 2013. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.01.012. PMID 23485013. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3718567

- "Stress, epigenetics, and alcoholism". Alcohol Research 34 (4): 495–505. 2012. PMID 23584115. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3860391

- "Brain chromatin remodeling: a novel mechanism of alcoholism". The Journal of Neuroscience 28 (14): 3729–37. April 2008. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5731-07.2008. PMID 18385331. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=6671100