The digital is increasingly present in everyday life, with a deep and growing social, political and economic impact, and society 5.0 is one of the possible attempts for this materialisation. However, the digital is not experienced by everyone in the same way, so this digitalisation of societies will have varied implications for individuals, namely the transformation of differences in access and digital literacy into new inequalities.

Sociology – as the scientific knowledge of the reciprocal influence of interactions between individuals and the influence of the social context – will have a heuristic potential for understanding this reality. Sociology will, thus, take on, concurrently with other sciences, a relevant role concerning the subsequent development of a more balanced society in this digital dimension, increasingly important in defining the social position of the individual, and, thus, will add to a development that materialises the potential of this digital society.

The digital is increasingly present in everyday life, with a deep and growing social, political and economic impact, and society 5.0 is one of the possible attempts for this materialisation. However, the digital is not experienced by everyone in the same way, so this digitalisation of societies will have varied implications for individuals, namely the transformation of differences in access and digital literacy into new inequalities. Sociology – as the scientific knowledge of the reciprocal influence of interactions between individuals and the influence of the social context – will have a heuristic potential for understanding this reality. Sociology will, thus, take on, concurrently with other sciences, a relevant role concerning the subsequent development of a more balanced society in this digital dimension, increasingly important in defining the social position of the individual, and, thus, will add to a development that materialises the potential of this digital society.

- Digital society, Society 5.0, Inequalities, Sociol

- Differences and inequalities in the digital society

1. Introduction

Inequalities may be regarded as differences that are deemed unfair (Therbon, 2006). Inequalities are multidimensional, not limiting to neither just one sector of society, nor a single resource, nor a single variable. Inequalities have a systemic and relational nature when addressing the causes and their effects (Therbon, 2006). The multidimensional component of inequalities values vital inequalities, i.e., inequalities in terms of life, death and health; existential inequalities, i.e., unequal recognition of human individuals as persons; resource inequalities, i.e., unequal distribution of resources. Inequalities in terms of resources include dimensions such as inequalities in income and wealth, education and professional qualification, cognitive and cultural skills, hierarchical position in organisations and access to social networks (Costa, 2012; Carmo, 2011; Therbon, 2006).

Inequalities may be regarded as differences that are deemed unfair[1]. Inequalities are multidimensional, not limiting to neither just one sector of society, nor a single resource, nor a single variable. Inequalities have a systemic and relational nature when addressing the causes and their effects[1]. The multidimensional component of inequalities values vital inequalities, i.e., inequalities in terms of life, death and health; existential inequalities, i.e., unequal recognition of human individuals as persons; resource inequalities, i.e., unequal distribution of resources. Inequalities in terms of resources include dimensions such as inequalities in income and wealth, education and professional qualification, cognitive and cultural skills, hierarchical position in organisations and access to social networks[2][3][1].

Inequalities in contemporary societies are global inequalities. They are characterised by the growing presence, in the multiple inequalities observable in local contexts and national societies, and shaped by global asymmetric social relationships; inequalities between countries, as they establish and evolve in the contemporary world in profound globalisation; social inequalities on a planetary scale, encompassing or traversing human society as a whole, in a context of globalised social interdependencies (Costa, 2012).

Inequalities in contemporary societies are global inequalities. They are characterised by the growing presence, in the multiple inequalities observable in local contexts and national societies, and shaped by global asymmetric social relationships; inequalities between countries, as they establish and evolve in the contemporary world in profound globalisation; social inequalities on a planetary scale, encompassing or traversing human society as a whole, in a context of globalised social interdependencies[2].

Currently, and with a growing presence in the future, the digital permeates the lives of practically all of us, and Society 5.0 is an example of a possible materialisation (Ferreira & Serpa, 2020). Society 5.0 is a recent concept, built on the notion of the functioning of a smart society based on the mobilisation of digital technology and artificial intelligence, adding to the social development and the consequent improvement in individuals’ quality of life, as well as to sustainability (Ferreira & Serpa, 2018, 2020; Gladden, 2019).

Currently, and with a growing presence in the future, the digital permeates the lives of practically all of us, and Society 5.0 is an example of a possible materialisation[4]. Society 5.0 is a recent concept, built on the notion of the functioning of a smart society based on the mobilisation of digital technology and artificial intelligence, adding to the social development and the consequent improvement in individuals’ quality of life, as well as to sustainability [5][6][7].

This progressive prominence of the digital necessarily entails a transformation of societal life at the micro (individual), meso (group/organisational) and macro (global) social levels (Serpa & Ferreira, 2020), with a profound influence on social interactions and structures.

This progressive prominence of the digital necessarily entails a transformation of societal life at the micro (individual), meso (group/organisational) and macro (global) social levels[4], with a profound influence on social interactions and structures.

This change has positive and/or negative consequences that can themselves shape new and profound social inequalities in a type of society that is sometimes presented as increasingly inclusive (Gladden, 2019). In this regard, Nadolu and Nadolu (2020) maintain that

This change has positive and/or negative consequences that can themselves shape new and profound social inequalities in a type of society that is sometimes presented as increasingly inclusive[7]. In this regard, Nadolu and Nadolu (2020)[8] maintain that

The digitalization of everyday life has become a common place reality for more than half of the global population. Being connected 24/7 on several devices, being only one click/touch away from a huge amount of digital content, being available for interactions with almost any users from around the globe have become routine. In this paper, we identify the main sociological dimensions of the so-called Homo interneticus — a new manifestation of the human condition — on the basis of new communication technologies (p. 1).

However, the digital is not impartial or neutral, either in access or in the use of the digital. Digital literacy or competence to handle it as a consumer, but also as a creator, consciously and intentionally, with digital technology in professional and non-professional daily life, is not guaranteed (Santos & Serpa, 2017, 2020a, 2020b). The promotion of abilities and competences in the digital world is not ensured even in new generations (Santos & Serpa, 2017; Spante, Hashemi, Lundin, & Algers, 2018). The disparities in the access to digital technology persist, and this gap calls into question the participation of citizens in decision-making processes.

However, the digital is not impartial or neutral, either in access or in the use of the digital. Digital literacy or competence to handle it as a consumer, but also as a creator, consciously and intentionally, with digital technology in professional and non-professional daily life, is not guaranteed[9][10][11]. The promotion of abilities and competences in the digital world is not ensured even in new generations[9][12]. The disparities in the access to digital technology persist, and this gap calls into question the participation of citizens in decision-making processes.

The induced digital gap defines the degree of digital citizenship for which, unified policies have yet to be drawn at various educational levels to reduce that gap. The quest for a broad participation to develop digital citizenship competencies needs further investigations into innovative educational approaches, pedagogical methods, and routine practices that foster digital literacy, and narrows the digital divide (Atif & Chou, 2018, p. 152).

The induced digital gap defines the degree of digital citizenship for which, unified policies have yet to be drawn at various educational levels to reduce that gap. The quest for a broad participation to develop digital citizenship competencies needs further investigations into innovative educational approaches, pedagogical methods, and routine practices that foster digital literacy, and narrows the digital divide[13].

Sociology may offer an important contribution by promoting theoretical and methodologically oriented empirical research on the dynamics of Society 5.0 and, potentially, develop relevant strategies and instruments in shaping political decisions in the process of fighting inequalities in the digital society. Ferreira and Serpa (2017) put forward four of the main structuring principles of Sociology as scientific knowledge, depicted in Table 1.

Sociology may offer an important contribution by promoting theoretical and methodologically oriented empirical research on the dynamics of Society 5.0 and, potentially, develop relevant strategies and instruments in shaping political decisions in the process of fighting inequalities in the digital society. Ferreira and Serpa (2017)[14] put forward four of the main structuring principles of Sociology as scientific knowledge, depicted in Table 1.

Table 1. Four Sociological principles

|

Sociological imagination |

Demystification of preconceived knowledge shared in society and which may be the result of being falsely conscious of their social positions |

|

Multi-paradigmatic |

Theoretical pluralism respecting different sociological orientations of sociology |

|

Heuristic interdisciplinarity |

Interdependence and complementarity between sciences |

|

Self-reflexivity |

Critical analysis of what is done, the conditions in which it is done, and the effects of one’s activity |

Source: Ferreira & Serpa (2017).

Source: Ferreira & Serpa (2017)[14].

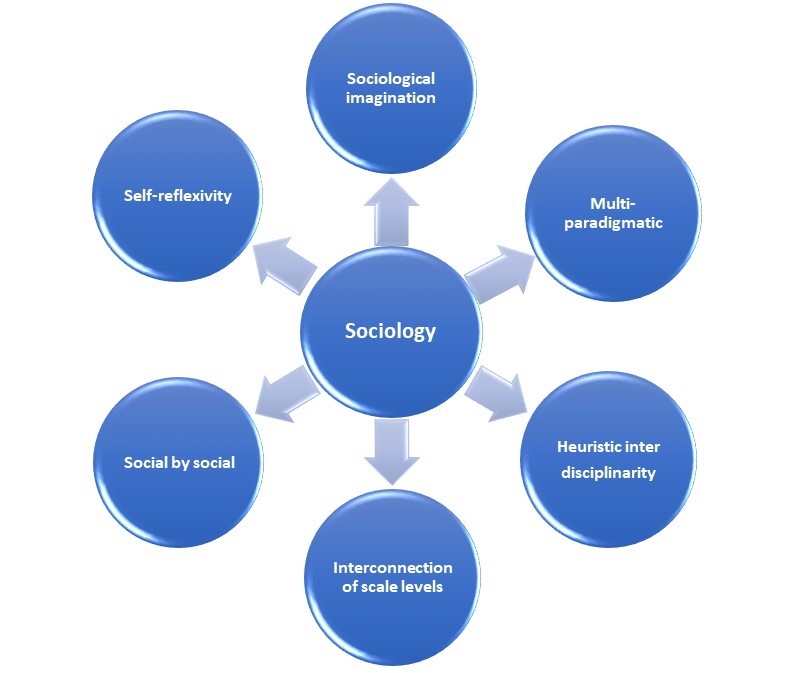

Sociology, as a form of scientific knowledge, can be defined as “a scientific discipline that perceives in its specific way the social reality, producing plural theoretical topics, formulating research problems within the context of these topics, and developing methodical strategies that guide empirical research” (Ferreira & Serpa, 2017, p. 1). The critical basis of this definition, as already put forth by Durkheim, is to explain the social through the social (Figure 1).

Sociology, as a form of scientific knowledge, can be defined as “a scientific discipline that perceives in its specific way the social reality, producing plural theoretical topics, formulating research problems within the context of these topics, and developing methodical strategies that guide empirical research”[14]. The critical basis of this definition, as already put forth by Durkheim, is to explain the social through the social (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Making Sociology

Thus, Sociology, together with other social sciences, due to the above-mentioned features, can provide relevant contributions to the promotion of smaller inequalities in increasingly digital societies, by fostering greater awareness of these inequalities and by promoting digital literacy competences. Digital literacy is regarded as

[…] the awareness, attitude and ability of individuals to appropriately use digital tools and facilities to identify, access, manage, integrate, evaluate, analyse and synthesize digital resources, construct new knowledge, create media expressions, and communicate with others, in the context of specific life situations, in order to enable constructive social action; and to reflect upon this process (Martin, 2006, p. 155).

[…] the awareness, attitude and ability of individuals to appropriately use digital tools and facilities to identify, access, manage, integrate, evaluate, analyse and synthesize digital resources, construct new knowledge, create media expressions, and communicate with others, in the context of specific life situations, in order to enable constructive social action; and to reflect upon this process[15].

Sociology may have heuristic potential in the development of a more balanced society, adding to a development that materialises the potential of this digital society, which is increasingly important in defining the individual’s social positioning, in a sociologically informed society.

References

Atif, Y., & Chou, C. (2018). Guest editorial: Digital citizenship: Innovations in education, practice, and pedagogy. Educational Technology & Society, 21(1), 152-154.

Carmo, R. (2011). O mundo é “enrugado” [The world is “wrinkled”]. In R. Campos, A.Brighenti, & L. Spinelli (Orgs.), Uma cidade de imagens. Produções e consumos visuais em meio urbano [A city of images. Visual productions and consumption in urban areas] (pp. 41-50). Lisbon: Editora Mundos Sociais.

Costa, A. (2012). Desigualdades globais [Global inequalities]. Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas, 68, 9-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.7458/SPP20126869

Ferreira, C. M., & Serpa, S. (2017). Challenges in the teaching of sociology in higher education. Contributions to a discussion. Societies, 7(4), 30, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc7040030

Ferreira, C. M., & Serpa, S. (2018). Society 5.0 and social development: Contributions to a discussion. Management and Organizational Studies, 5(4), 26-31. https://doi.org/10.5430/mos.v5n4p26

Ferreira, C. M., & Serpa, S. (2020). Society 5.0. Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://encyclopedia.pub/321

Gladden, M. E. (2019). Who will be the members of Society 5.0? Towards an anthropology of technologically posthumanized future societies. Social Sciences, 8(5), 148, 1-39. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8050148

Martin, A. (2006). A European framework for digital literacy. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 22(1), 151-161. Retrieved from https://www.idunn.no/dk/2006/02/a_european_framework_for_digital_literacy

Nadolu, B., & Nadolu, D. (2020). Homo interneticus – The sociological reality of mobile online being. Sustainability, 12(5), 1800, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051800

Santos, A. I., & Serpa, S. (2017). The importance of promoting digital literacy in higher education. International Journal of Social Science Studies, 5(6), 90-93. https://doi.org/10.11114/ijsss.v5i6.2330

Santos, A. I., & Serpa, S. (2020a). Digital literacy. Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://encyclopedia.pub/103

Santos, A. I., & Serpa, S. (2020b). Literacy: Promoting sustainability in a digital society. Journal of Education, Teaching and Social Studies, 2(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.22158/jetss.v2n1p1

Serpa, S., & Ferreira, C. M. (2020). Sociology. Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://encyclopedia.pub/305

Spante, M., Hashemi, S. S., Lundin, M., & Algers, A. (2018). Digital competence and digital literacy in higher education research: Systematic review of concept use. Cogent Education, 5(1), 1519143. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2018.1519143

Therborn, G. (2006). Meaning, mechanisms, patterns, and forces: An introduction. In G. Therborn (Org.), Inequalities of the world (pp. 1-58). London: Verso.

Authors

Sandro Serpa

University of the Azores, Faculty of Social and Human Sciences, Department of Sociology;

Interdisciplinary Centre of Social Sciences – CICS.UAc/CICS.NOVA.UAc;

Interdisciplinary Centre for Childhood and Adolescence – NICA – UAc. PORTUGAL.

Carlos Miguel Ferreira

ISCTE –University Institute of Lisbon;

Interdisciplinary Centre of Social Sciences – CICS.NOVA;

Estoril Higher Institute for Tourism and Hotel Studies, Portugal.

Sociology may have heuristic potential in the development of a more balanced society, adding to a development that materialises the potential of this digital society, which is increasingly important in defining the individual’s social positioning, in a sociologically informed society.

References

- Therborn, G. (2006). Meaning, mechanisms, patterns, and forces: An introduction. In G. Therborn (Org.), Inequalities of the world (pp. 1-58). London: Verso.

- Costa, A. (2012). Desigualdades globais [Global inequalities]. Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas, 68, 9-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.7458/SPP20126869

- Carmo, R. (2011). O mundo é “enrugado” [The world is “wrinkled”]. In R. Campos, A.Brighenti, & L. Spinelli (Orgs.), Uma cidade de imagens. Produções e consumos visuais em meio urbano [A city of images. Visual productions and consumption in urban areas] (pp. 41-50). Lisbon: Editora Mundos Sociais.

- Serpa, S., & Ferreira, C. M. (2020). Sociology. Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://encyclopedia.pub/305

- Ferreira, C. M., & Serpa, S. (2018). Society 5.0 and social development: Contributions to a discussion. Management and Organizational Studies, 5(4), 26-31. https://doi.org/10.5430/mos.v5n4p26

- Ferreira, C. M., & Serpa, S. (2020). Society 5.0. Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://encyclopedia.pub/321

- Gladden, M. E. (2019). Who will be the members of Society 5.0? Towards an anthropology of technologically posthumanized future societies. Social Sciences, 8(5), 148, 1-39. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8050148

- Nadolu, B., & Nadolu, D. (2020). Homo interneticus – The sociological reality of mobile online being. Sustainability, 12(5), 1800, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051800

- Santos, A. I., & Serpa, S. (2017). The importance of promoting digital literacy in higher education. International Journal of Social Science Studies, 5(6), 90-93. https://doi.org/10.11114/ijsss.v5i6.2330

- Santos, A. I., & Serpa, S. (2020a). Digital literacy. Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://encyclopedia.pub/103

- Santos, A. I., & Serpa, S. (2020b). Literacy: Promoting sustainability in a digital society. Journal of Education, Teaching and Social Studies, 2(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.22158/jetss.v2n1p1

- Spante, M., Hashemi, S. S., Lundin, M., & Algers, A. (2018). Digital competence and digital literacy in higher education research: Systematic review of concept use. Cogent Education, 5(1), 1519143. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2018.1519143

- Atif, Y., & Chou, C. (2018). Guest editorial: Digital citizenship: Innovations in education, practice, and pedagogy. Educational Technology & Society, 21(1), 152-154.

- Ferreira, C. M., & Serpa, S. (2017). Challenges in the teaching of sociology in higher education. Contributions to a discussion. Societies, 7(4), 30, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc7040030

- Martin, A. (2006). A European framework for digital literacy. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 22(1), 151-161. Retrieved from https://www.idunn.no/dk/2006/02/a_european_framework_for_digital_literacy