You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Sirius Huang and Version 1 by Qi Huang.

Tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) may differentiate into different patterns under the stimulation of different factors, and they play a dual role in the occurrence and progression of tumors in direct or indirect ways.

- tumor-associated neutrophils

- colorectal cancer

- immune-checkpoint-inhibitor therapy

1. Introduction

Cancer may surpass cardiovascular diseases as a leading cause of death in many countries [1]. According to global cancer statistics in 2020, new cases and new deaths of colorectal cancer (CRC) account for 10.0% and 9.4% of all new cases and deaths worldwide, respectively [2]. The CRC incidence rate and mortality ranked among the top three in both men and women. With the improvement in the screening and treatment level, the incidence rate and mortality of CRC in developed countries have shown a decreasing trend. However, the incidence rate of CRC is rising rapidly in many developing countries, represented by China, with the changes in diet and lifestyle in recent decades [3,4][3][4]. CRC treatment mainly includes surgery, chemoradiotherapy and targeted therapy. Patients in different stages choose different treatment strategies according to the extent of the tumor invasion. Targeted therapies based on epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), v-RAF murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B (BRAF) and other targets have been widely used, significantly improving the survival of CRC patients [5]. In recent years, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) based on programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1), and cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4), which can activate T cells to achieve antitumor effects, have achieved promising results. However, ICIs are not applicable for everyone. In CRC, less than 10% of patients with microsatellite-instability-high (MSI-H) or deficient-DNA-mismatch (dMMR) CRC showed a significant response to ICIs, while most microsatellite-stability (MSS)/proficient-mismatch-repair (pMMR) patients displayed poor efficacy [6]. Precision therapy based on operable targets is important to improve the survival of CRC patients.

The tumor immune microenvironment (TME) has been found to play a crucial role in tumor progression, including in CRC [7]. In the TME, the immune cells include T cells, natural killer cells, macrophages, neutrophils and so on. They all have different effects in antitumor immunity [8]. At present, there are relatively few studies on the neutrophil infiltration in the tumor microenvironment, and their functions have not been fully explained, which is still controversial. In human peripheral blood, neutrophils account for 50–70% of the circulating leukocytes. As short-lived cells, neutrophils play an indispensable role in both healthy and tumor tissues [9,10][9][10]. Similar to tumor-associated macrophages, neutrophils can differentiate into antitumor and protumor tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) under the chemotaxis of different factors, and they are also defined as N1 and N2, although it is unclear whether this classification is applicable to humans [11]. Interferon β (IFN-β) induces neutrophil polarization to an antitumor N1 phenotype [12], whereas transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) promotes the generation of protumor N2 neutrophils [11]. Interestingly, with the tumor progression, the N1 phenotype can turn into the N2 phenotype [13]. N1-TANs enhance the tumor cytotoxicity and attenuate immune suppression by producing tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), reactive oxygen species (ROS) and apoptosis-related factor (Fas), and by reducing the expression of arginase, while N2-TANs participate in tumor migration and metastasis through the expressions of arginase, matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9), VEGF and chemokines [11]. A number of researchers have reported that TANs play a crucial role in regulating the progress and prognosis of CRC, but the mechanism by which TANs regulate CRC remains poorly characterized.

2. Two-Faced Role of TANs in Tumor Progression

As the first line of defense against inflammation and infection, neutrophils are recruited from the vascular system to tissues via chemokines to play an anti-infection role. However, the dysregulation of neutrophil chemotaxis and activation may lead to a variety of diseases, including cancer [14]. The presence, recruitment and activation of TANs play a significant role in maintaining the TME and tumor progression.

A series of studies have revealed the possible antitumor mechanisms of TANs. Sunil Singhal demonstrated that the TAN subset from CD11b+CD15highCD10−CD16low immature progenitors exhibited an antitumor function in the early stages of human cancer [15]. Neutrophils infiltrating cancer cells exert an antitumor function via the expressions of costimulatory receptors, including 4-1BBL, OX40L and CD86, thereby producing active T cells and secreting interferon γ (IFN-γ) [16]. Neutrophils are capable of directly killing cancer cells via the secretion of cytotoxic substances, such as ROS, nitric oxide (NO) and neutrophil elastase (NE) [17]. H2O2 secreted by neutrophils relies on the Ca2+ channel to kill cancer cells, which regulates the expression of transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily M member 2 (TRPM2) to inhibit cancer-cell proliferation [18]. Neutrophil-derived hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)-/mesenchymal–epithelial transition factor (MET)-dependent NO can promote the killing of cancer cells, which abates tumor growth and metastasis [19]. Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-induced ligand (TRAIL) promotes cancer-cell death by binding to the TRAIL receptors on the cell surface, and it exhibits important antitumor activity. This mechanism has also been observed in chronic myeloid leukemia patients, inducing leukemia-cell apoptosis [20,21][20][21]. In addition to releasing cytotoxic substances, TANs can also release various chemokines and cytokines to stimulate the proliferation and activation of immune cells, such as T cells, NK cells and dendritic cells (DCs), thereby initiating antitumor immune responses [22]. CD8+ T cells can be recruited and activated by cytokines secreted by TANs, including the C-C motif chemokine ligand (CCL)-3, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand (CXCL)-10, TNF-α and interleukin (IL)-12 [23]. IFN-γ-stimulated TANs activate NK cells by releasing IL-18 [24], and TANs promote DC activation via the secretion of TNF-α [25]. Neutrophil-derived VEGF-A165b mediates angiogenesis inhibition [26].

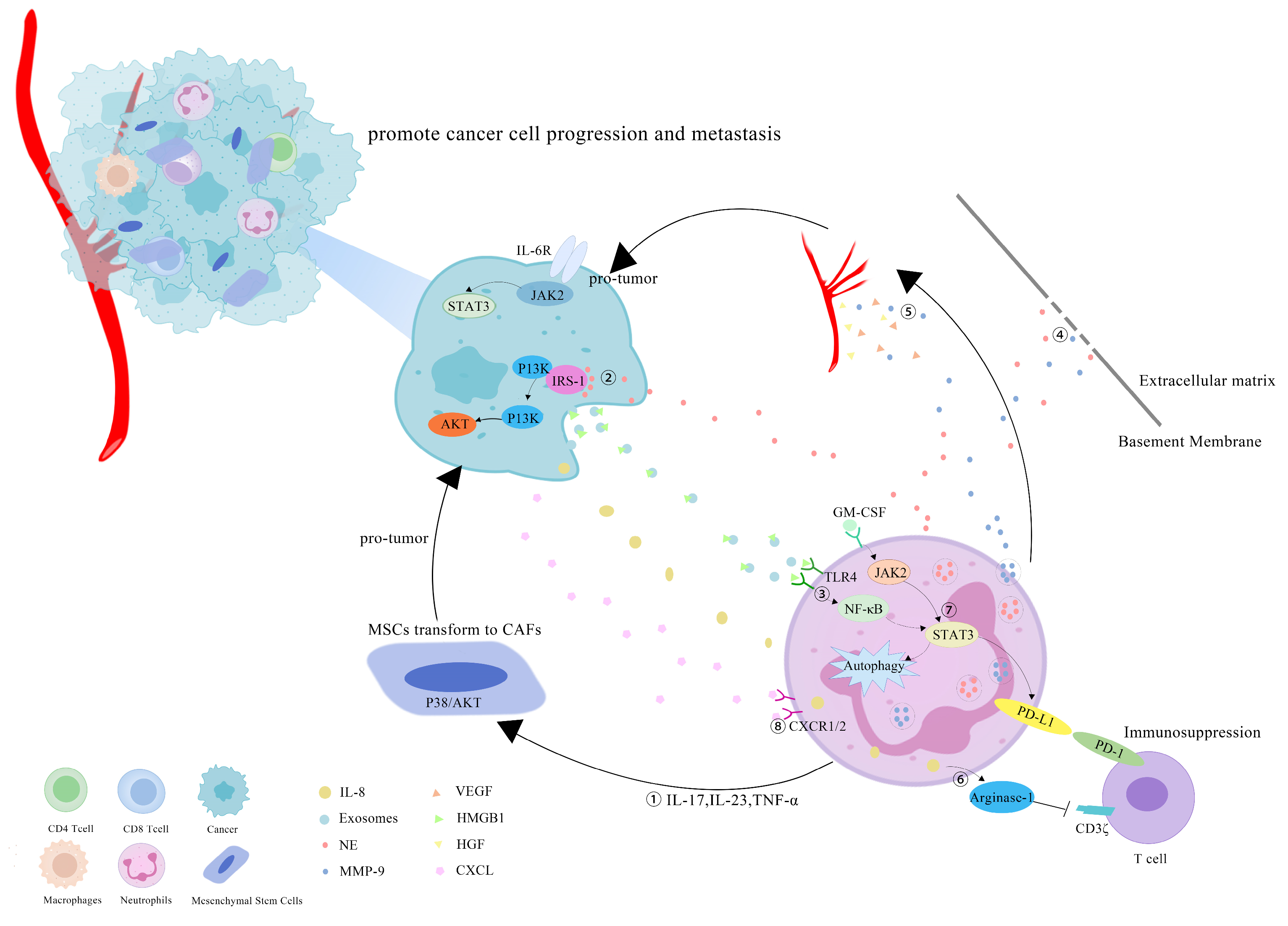

However, more research has revealed that TANs may promote tumor progression through cancer-cell proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis and immunosuppression (Figure 1). Studies have investigated that TANs can induce mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) to transform into tumor-related fibroblasts (CAF) by secreting IL-17, IL-23 and TNF-α, activating the protein kinase B/p38 (Akt/p38) pathway and ultimately promoting the proliferation and metastases of tumor cells [27]. IL-17 can also promote cancer-cell proliferation by activating the Janus kinase 2/signal transducers and activators of the transcription (JAK2/STAT3) pathway [28]. Moreover, neutrophils can be polarized into the N2 phenotype by tumor cells to promote the proliferation and migration of tumor cells. Tumor-cell-derived exosomes transport high-mobility group box-1 (HMGB1) to interact with Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and activate the neutrophil nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) pathway [29]. The tumorigenic mechanism of TANs also includes the reduction in the antitumor response of CD8+ T cells by the secretion of arginase-1, and the binding of TAN-derived NE to insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1), both of which lead to cell proliferation [30,31,32][30][31][32]. TANs accelerate local tumor invasion by secreting MMP9 and NE to modify and degrade the extracellular matrix (ECM) [33]. HGF also contributes to local tumor invasion through the focal adhesion kinase (FAK)/paxillin signaling pathways [34]. Neutrophils have a unique ability to release chromatin reticulum, and namely, neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). NETs can help circulating tumor cells enter the vascular system, promote their intravascular flow at the distal site and finally boost the invasion and metastases of tumor cells [35]. It has been shown that granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IL-5 and tumor-derived protease cathepsin C (CTSC) are all correlated with neutrophil recruitment and activation and promote lung metastases [36,37][36][37]. TAN-derived VEGF, HGF and MMP9 also make cancer cells more aggressive and facilitate angiogenesis [38]. Research conducted by Ting-ting Wang clarified that the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway is related to neutrophils in tumor immunosuppression, and it was shown that TANs were activated by GM-CSF and the induced high-level expression of the immunosuppressive molecule PD-L1 by the activation of the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway [39]. Tumor-derived IL-8 induces neutrophils to secret arginase-1, resulting in arginase depletion and the establishment of an immunosuppressive TME [40]. Moreover, chemokines produced by tumor cells, such as the CXCL1,2,5,8/CXCR1/2 signaling axis, can promote neutrophil recruitment, forming positive feedback with the tumor-promoting effect of TANs [41,42][41][42]. Chemokine receptors, such as CCR2 and CCR5, have also been implicated in neutrophil mobilization, recruitment and tissue infiltration [43,44][43][44].

Figure 1. Mechanisms of TANs that promote tumor progression: (1) TANs secrete cytokines, such as IL-17, IL-23 and TNF-α, to induce MSCs to convert into CAFs, and to promote tumor-cell proliferation; (2) TANs secrete NE to bind intracellular IRS-1, releasing its inhibitory effect on the PI3K/Akt pathway, and promoting tumor proliferation; (3) cell-derived exosomes induce the autophagy and N2 polarization of neutrophils via HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB signaling to promote cancer-cell proliferation and migration; (4) TANs secrete NE and MMP-9 to degrade the ECM and accelerate the tumor invasion; (5) TAN-derived VEGF, HGF and MMP9 promote the angiogenesis of tumor cells; (6) tumor-derived IL-8 induces neutrophils to secret arginase-1, resulting in arginase depletion and the establishment of an immunosuppressive TME; (7) GM-CSF activates TANs to express high levels of the immunosuppressive molecule PD-L1 through the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway; (8) neutrophils can be recruited by tumor cells through chemokines, such as the CXCL/CXCR1/2 signal axis.

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Weiderpass, E.; Soerjomataram, I. The ever-increasing importance of cancer as a leading cause of premature death worldwide. Cancer 2021, 127, 3029–3030.

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249.

- Qiu, H.; Cao, S.; Xu, R. Cancer incidence, mortality, and burden in China: A time-trend analysis and comparison with the United States and United Kingdom based on the global epidemiological data released in 2020. Cancer Commun. 2021, 41, 1037–1048.

- Arnold, M.; Sierra, M.S.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Gut 2017, 66, 683–691.

- Mohamed, A.A.; Lau, D.K.; Chau, I. HER2 targeted therapy in colorectal cancer: New horizons. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2022, 105, 102363.

- Ganesh, K. Optimizing immunotherapy for colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 19, 93–94.

- Roma-Rodrigues, C.; Mendes, R.; Baptista, P.V.; Fernandes, A.R. Targeting Tumor Microenvironment for Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 840.

- Lei, X.; Lei, Y.; Li, J.K.; Du, W.X.; Li, R.G.; Yang, J.; Li, J.; Li, F.; Tan, H.B. Immune cells within the tumor microenvironment: Biological functions and roles in cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2020, 470, 126–133.

- Eruslanov, E.B.; Singhal, S.; Albelda, S.M. Mouse versus Human Neutrophils in Cancer: A Major Knowledge Gap. Trends Cancer 2017, 3, 149–160.

- Ballesteros, I.; Rubio-Ponce, A.; Genua, M.; Lusito, E.; Kwok, I.; Fernandez-Calvo, G.; Khoyratty, T.E.; van Grinsven, E.; Gonzalez-Hernandez, S.; Nicolas-Avila, J.A.; et al. Co-Option of Neutrophil Fates by Tissue Environments. Cell 2020, 183, 1282–1297.e18.

- Fridlender, Z.G.; Sun, J.; Kim, S.; Kapoor, V.; Cheng, G.; Ling, L.; Worthen, G.S.; Albelda, S.M. Polarization of tumor-associated neutrophil phenotype by TGF-β: “N1” versus “N2” TAN. Cancer Cell 2009, 16, 183–194.

- Andzinski, L.; Kasnitz, N.; Stahnke, S.; Wu, C.F.; Gereke, M.; von Kockritz-Blickwede, M.; Schilling, B.; Brandau, S.; Weiss, S.; Jablonska, J. Type I IFNs induce anti-tumor polarization of tumor associated neutrophils in mice and human. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 138, 1982–1993.

- Jaillon, S.; Ponzetta, A.; Di Mitri, D.; Santoni, A.; Bonecchi, R.; Mantovani, A. Neutrophil diversity and plasticity in tumour progression and therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 485–503.

- Taucher, E.; Taucher, V.; Fink-Neuboeck, N.; Lindenmann, J.; Smolle-Juettner, F.M. Role of Tumor-Associated Neutrophils in the Molecular Carcinogenesis of the Lung. Cancers 2021, 13, 5972.

- Singhal, S.; Bhojnagarwala, P.S.; O’Brien, S.; Moon, E.K.; Garfall, A.L.; Rao, A.S.; Quatromoni, J.G.; Stephen, T.L.; Litzky, L.; Deshpande, C.; et al. Origin and Role of a Subset of Tumor-Associated Neutrophils with Antigen-Presenting Cell Features in Early-Stage Human Lung Cancer. Cancer Cell 2016, 30, 120–135.

- Eruslanov, E.B.; Bhojnagarwala, P.S.; Quatromoni, J.G.; Stephen, T.L.; Ranganathan, A.; Deshpande, C.; Akimova, T.; Vachani, A.; Litzky, L.; Hancock, W.W.; et al. Tumor-associated neutrophils stimulate T cell responses in early-stage human lung cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 5466–5480.

- Masucci, M.T.; Minopoli, M.; Carriero, M.V. Tumor Associated Neutrophils. Their Role in Tumorigenesis, Metastasis, Prognosis and Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1146.

- Gershkovitz, M.; Caspi, Y.; Fainsod-Levi, T.; Katz, B.; Michaeli, J.; Khawaled, S.; Lev, S.; Polyansky, L.; Shaul, M.E.; Sionov, R.V.; et al. TRPM2 Mediates Neutrophil Killing of Disseminated Tumor Cells. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 2680–2690.

- Finisguerra, V.; Di Conza, G.; Di Matteo, M.; Serneels, J.; Costa, S.; Thompson, A.A.; Wauters, E.; Walmsley, S.; Prenen, H.; Granot, Z.; et al. MET is required for the recruitment of anti-tumoural neutrophils. Nature 2015, 522, 349–353.

- Tanaka, H.; Ito, T.; Kyo, T.; Kimura, A. Treatment with IFNα in vivo up-regulates serum-soluble TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand (sTRAIL) levels and TRAIL mRNA expressions in neutrophils in chronic myelogenous leukemia patients. Eur. J. Haematol. 2007, 78, 389–398.

- Tecchio, C.; Huber, V.; Scapini, P.; Calzetti, F.; Margotto, D.; Todeschini, G.; Pilla, L.; Martinelli, G.; Pizzolo, G.; Rivoltini, L.; et al. IFNα-stimulated neutrophils and monocytes release a soluble form of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL/Apo-2 ligand) displaying apoptotic activity on leukemic cells. Blood 2004, 103, 3837–3844.

- Riise, R.E.; Bernson, E.; Aurelius, J.; Martner, A.; Pesce, S.; Della Chiesa, M.; Marcenaro, E.; Bylund, J.; Hellstrand, K.; Moretta, L.; et al. TLR-Stimulated Neutrophils Instruct NK Cells To Trigger Dendritic Cell Maturation and Promote Adaptive T Cell Responses. J. Immunol. 2015, 195, 1121–1128.

- Raftopoulou, S.; Valadez-Cosmes, P.; Mihalic, Z.N.; Schicho, R.; Kargl, J. Tumor-Mediated Neutrophil Polarization and Therapeutic Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3218.

- Sun, R.; Luo, J.; Li, D.; Shu, Y.; Luo, C.; Wang, S.S.; Qin, J.; Zhang, G.M.; Feng, Z.H. Neutrophils with protumor potential could efficiently suppress tumor growth after cytokine priming and in presence of normal NK cells. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 12621–12634.

- Spiegel, A.; Brooks, M.W.; Houshyar, S.; Reinhardt, F.; Ardolino, M.; Fessler, E.; Chen, M.B.; Krall, J.A.; DeCock, J.; Zervantonakis, I.K.; et al. Neutrophils Suppress Intraluminal NK Cell-Mediated Tumor Cell Clearance and Enhance Extravasation of Disseminated Carcinoma Cells. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 630–649.

- Loffredo, S.; Borriello, F.; Iannone, R.; Ferrara, A.L.; Galdiero, M.R.; Gigantino, V.; Esposito, P.; Varricchi, G.; Lambeau, G.; Cassatella, M.A.; et al. Group V Secreted Phospholipase A2 Induces the Release of Proangiogenic and Antiangiogenic Factors by Human Neutrophils. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 443.

- Zhang, J.; Ji, C.; Li, W.; Mao, Z.; Shi, Y.; Shi, H.; Ji, R.; Qian, H.; Xu, W.; Zhang, X. Tumor-Educated Neutrophils Activate Mesenchymal Stem Cells to Promote Gastric Cancer Growth and Metastasis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 788.

- Li, S.; Cong, X.; Gao, H.; Lan, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, W.; Song, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, H.; et al. Tumor-associated neutrophils induce EMT by IL-17a to promote migration and invasion in gastric cancer cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 6.

- Zhang, X.; Shi, H.; Yuan, X.; Jiang, P.; Qian, H.; Xu, W. Tumor-derived exosomes induce N2 polarization of neutrophils to promote gastric cancer cell migration. Mol. Cancer 2018, 17, 146.

- Rotondo, R.; Barisione, G.; Mastracci, L.; Grossi, F.; Orengo, A.M.; Costa, R.; Truini, M.; Fabbi, M.; Ferrini, S.; Barbieri, O. IL-8 induces exocytosis of arginase 1 by neutrophil polymorphonuclears in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 125, 887–893.

- Rodriguez, P.C.; Zea, A.H.; Culotta, K.S.; Zabaleta, J.; Ochoa, J.B.; Ochoa, A.C. Regulation of T cell receptor CD3zeta chain expression by L-arginine. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 21123–21129.

- Houghton, A.M.; Rzymkiewicz, D.M.; Ji, H.; Gregory, A.D.; Egea, E.E.; Metz, H.E.; Stolz, D.B.; Land, S.R.; Marconcini, L.A.; Kliment, C.R.; et al. Neutrophil elastase-mediated degradation of IRS-1 accelerates lung tumor growth. Nat. Med. 2010, 16, 219–223.

- Swierczak, A.; Mouchemore, K.A.; Hamilton, J.A.; Anderson, R.L. Neutrophils: Important contributors to tumor progression and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2015, 34, 735–751.

- Jiang, W.G.; Martin, T.A.; Parr, C.; Davies, G.; Matsumoto, K.; Nakamura, T. Hepatocyte growth factor, its receptor, and their potential value in cancer therapies. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2005, 53, 35–69.

- Cools-Lartigue, J.; Spicer, J.; McDonald, B.; Gowing, S.; Chow, S.; Giannias, B.; Bourdeau, F.; Kubes, P.; Ferri, L. Neutrophil extracellular traps sequester circulating tumor cells and promote metastasis. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 128, 3446–3458.

- Quail, D.F.; Olson, O.C.; Bhardwaj, P.; Walsh, L.A.; Akkari, L.; Quick, M.L.; Chen, I.C.; Wendel, N.; Ben-Chetrit, N.; Walker, J.; et al. Obesity alters the lung myeloid cell landscape to enhance breast cancer metastasis through IL5 and GM-CSF. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 974–987.

- Xiao, Y.; Cong, M.; Li, J.; He, D.; Wu, Q.; Tian, P.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S.; Liang, C.; Liang, Y.; et al. Cathepsin C promotes breast cancer lung metastasis by modulating neutrophil infiltration and neutrophil extracellular trap formation. Cancer Cell 2021, 39, 423–437.e7.

- Jablonska, J.; Leschner, S.; Westphal, K.; Lienenklaus, S.; Weiss, S. Neutrophils responsive to endogenous IFN-β regulate tumor angiogenesis and growth in a mouse tumor model. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 1151–1164.

- Wang, T.T.; Zhao, Y.L.; Peng, L.S.; Chen, N.; Chen, W.; Lv, Y.P.; Mao, F.Y.; Zhang, J.Y.; Cheng, P.; Teng, Y.S.; et al. Tumour-activated neutrophils in gastric cancer foster immune suppression and disease progression through GM-CSF-PD-L1 pathway. Gut 2017, 66, 1900–1911.

- Sparmann, A.; Bar-Sagi, D. Ras-induced interleukin-8 expression plays a critical role in tumor growth and angiogenesis. Cancer Cell 2004, 6, 447–458.

- Katoh, H.; Wang, D.; Daikoku, T.; Sun, H.; Dey, S.K.; Dubois, R.N. CXCR2-expressing myeloid-derived suppressor cells are essential to promote colitis-associated tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 2013, 24, 631–644.

- Faget, J.; Peters, S.; Quantin, X.; Meylan, E.; Bonnefoy, N. Neutrophils in the era of immune checkpoint blockade. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e002242.

- He, Z.; Wei, G.; Li, N.; Niu, M.; Gong, S.; Wu, G.; Wang, T.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, P. CCR2 and CCR5 promote diclofenac-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Naunyn Schmiedeb. Arch. Pharmacol. 2019, 392, 287–297.

- Xu, P.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, G.; Wang, C.Y.; Zhang, J. CCR2 dependent neutrophil activation and mobilization rely on TLR4-p38 axis during liver ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2017, 9, 2878–2890.

More