CYP3A is an enzyme subfamily in the cytochrome P450 (CYP) superfamily and includes isoforms CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP3A7, and CYP3A43. CYP3A enzymes are indiscriminate toward substrates and are unique in that these enzymes metabolize both endogenous compounds and diverse xenobiotics. Constitutive regulation of CYP3A4 transcription, both positive and negative, is mediated by hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α (HNF4α) and other hepatic transcription factors. CYP3A4 expression is modulated by various mechanisms involving nuclear receptors, hormones, xenobiotics, and signaling molecules. CYP3A4 is regulated by a large number of xenobiotics, including many drugs, endogenous compounds, and many hormones, such as triiodothyronine, dexamethasone, and growth hormone. Xenobiotic- and endobiotic-mediated CYP3A4 induction is indirect and entails activation of such ligand-dependent nuclear receptors as PXR, CAR, VDR, glucocorticoid receptor (GR) α, estrogen receptor (ER) α, bile acid receptor (farnesoid X receptor; FXR), oxysterol receptor (liver X receptor; LXR), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) as well as by binding to the three major cis-acting modules: CLEM4, distal XREM, and prPXRE.

CYP3A is an enzyme subfamily in the cytochrome P450 (CYP) superfamily and includes isoforms CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP3A7, and CYP3A43. CYP enzymes are responsible for approximately three-quarters of all drug metabolism reactions in the human body. CYP enzymes are involved in many critical metabolic reactions, including the metabolism of steroid hormones, bile acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, leukotrienes, and eicosanoids. CYP3A enzymes are widely expressed in human organs and tissues, and consequences of these enzymes’ activities play a major role both in normal regulation of physiological levels of endogenous compounds and in various pathological conditions.

- CYP3A

- CYP3A regulation

- CYP3A endogenous substrates

- drug-metabolizing enzymes

1. Introduction

The CYP3A subfamily is affiliated with the cytochrome P450 (CYP) superfamily, which represents monooxygenases that catalyze the breakdown of various substances via hydroxylation and epoxidation with the participation of an electron donor (NADPH) and molecular oxygen [1]. CYP enzymes function as the first line of defense against exogenous chemical agents [2]. CYP enzymes are responsible for approximately three-quarters of all drug metabolism reactions in the human body [3][4][3,4]. CYP enzymes are involved in many critical metabolic reactions, including the metabolism of steroid hormones, bile acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, leukotrienes, and eicosanoids [3].

Genes of CYP enzymes have been found in the genetic material of representatives of all kingdoms of living organisms, including plants. There are 57 known functional CYP genes in the human genome, aside from 58 pseudogenes whose protein products are enzymes metabolizing a wide range of endogenous and exogenous chemical compounds [2][5][6][2,5,6]. The genes of CYP enzymes are categorized into 18 families and 43 subfamilies based on the percentage of amino acid sequence homology. Just 3 families—CYP2, CYP3, and CYP4—contain more genes than the other 15 families combined [4][7][3,7]. The human CYP3 family consists of a single subfamily, CYP3A, which contains four genes (CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP3A7, and CYP3A43) encoding four functional enzymes [5][6][8][9][10][5,6,8-10].

CYP3A is a major subfamily in the cytochrome P450 superfamily. CYP3A enzymes are involved in the metabolism of more than 30% [11] and according to other reports 45–60% [12][13][14][12,13] of all pharmaceutical drugs currently on the market. CYP3A enzymes also metabolize some endogenous substrates, including hormones and bile acids, as well as nonpharmaceutical xenobiotics [11][12][13][11,12,14].

Expression of CYP3A enzymes is regulated and varies under the influence of various exogenous (drugs, chemicals, and diets) and endogenous factors (fatty acids, hormones, cytokines, and microRNAs [miRs or miRNAs]) [11].

CYP3A enzymes’ activity can be influenced by anthropogenic environmental chemicals: organophosphates, carbamates, parabens, benzotriazole UV stabilizers, and plasticizers [11][12][11,12]. Natural compounds present in foods—e.g., flavonoids found in fruits and vegetables, coffee, tea, chocolate, and wine—can alter CYP3A enzymes’ expression [15]. A prime example is the inhibition of CYP3A enzymes’ expression by components of grapefruit juice [12][16][12,16]. There is experimental evidence that retinoids can regulate the expression of CYP3A genes [17]. Certain diets, such as high-fat diets, can alter the expression of CYP3A genes [18], and it is likely that human dietary habits can affect basal expression of these genes [11].

Many of these substances are in turn metabolized by induced CYP3A enzymes, and this feedback mechanism implements detoxification of potentially harmful compounds [12].

2. Mechanisms of CYP3A Regulation

1.1. Members of the CYP3A Subfamily: Localization of Genes in the Genome and of Enzymes in Tissues of the Body

CYP3A4To expression is modulated by various mechanisms involving nuclear receptors, hormones, xenobiotics,date, four functional enzymes belonging to the CYP3A subfamily have been identified in humans: CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP3A7, and CYP3A43 [5,6,8,9]. Each gene contains 13 exons with conserved exon–intron boundaries [10,19]. CYP3A isoenzymes are expressed mainly in the liver and signaling molecules.mall intestine CYP3A4 ias rwegulated by a large number of xenobiotics, including many drugs, endogenous compoundll as in the kidneys, adrenal glands, lungs, brain, prostate, testes, placenta, pancreas, and maskeletal muscles [5,6,8,9,11,14,20-23].

Iny hormones, such as triiodothyronine, dexamethasone, and growth hormonthe CYP3A subfamily, CYP3A4 is the major member participating in drug metabolism and is the predominant form of CYP3A in the [19].

Xlivenobiotic-r (10–50%) and endobiotic-mediatedsmall intestine (40%) of adult humans. CYP3A4 induction is indirec5 is the most abundant and entails activation of such ligand-dependent nuclear receptors as PXR, CAR, VDR, glucocorticoid receptor (GR) α, estrogen receptor (ER) α, bile acid receptor (farnesoid X receptor; FXR), oxysterol receptor (liver X receptor; LXR), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) [10][11][14][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34] abest studied among minor isoforms of CYP3A [6,8]. CYP3A7 and CYP3A43 are underexpressed as compared to CYP3A4/5 [6,8]. Protein expression of CYP3A43 in human liver microsomes is ~15 times lower than that of CYP3A4 [24]. CYP3A7, a predominantly fetoplacental enzyme, is highly expressed in the liver and intestines of the embryo and fetus as well as byin the binding to the three majorendometrium and placenta, although it is detectable in the liver and small cis-acintestinge of modules: CLEM4, distalsome adults [5,6,8,12,23,25]. Among the CYP3A XREMgenes, CYP3A43 wand prPXRE (Figure 1) [10].

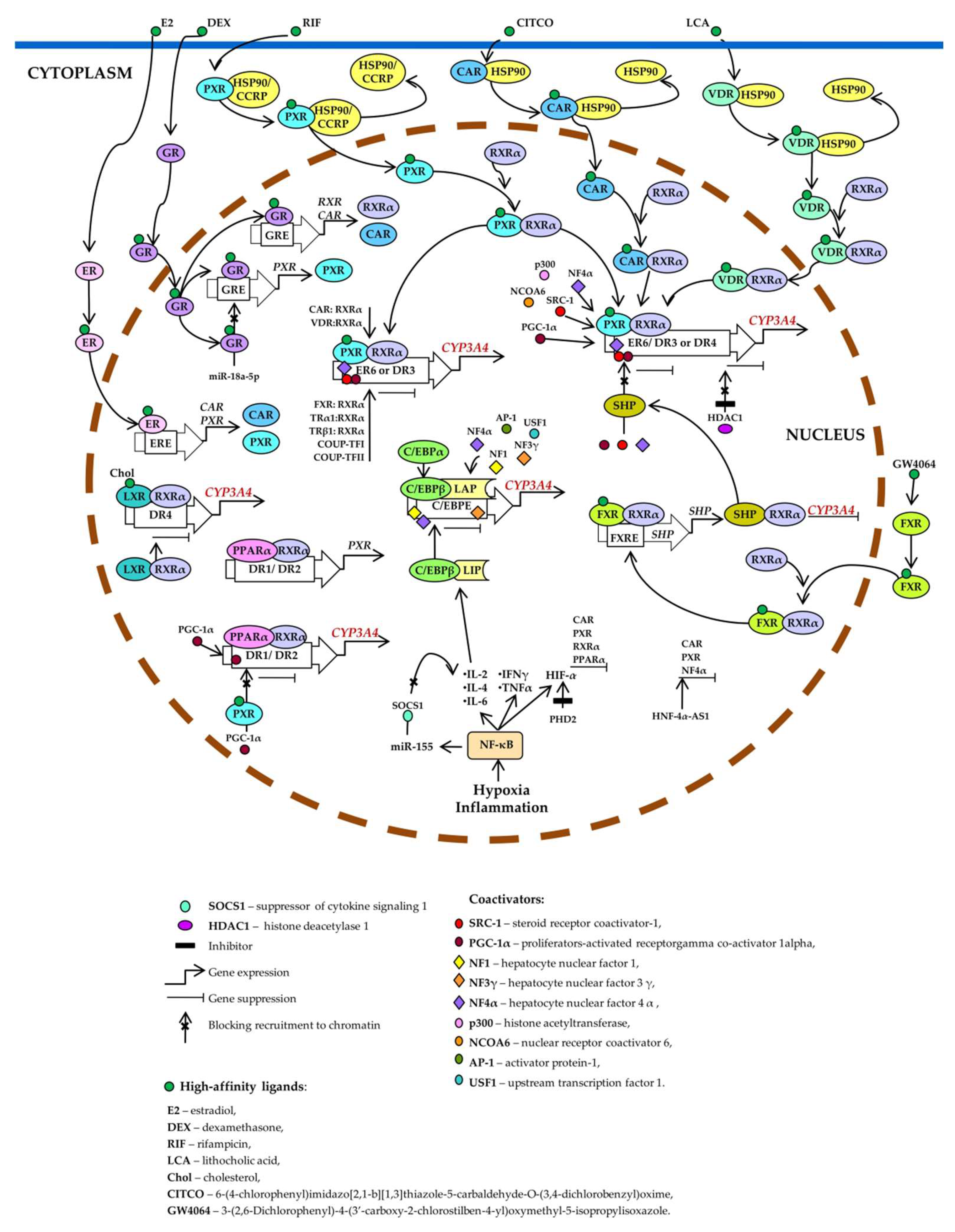

Figure 1. Trs the lanscriptional regulation oft to be identified. CYP3A4. Pregnane X receptor (PXR), constitutive androstane receptor (CAR), and vitamin D receptor (VDR) control basal3 expression is highest in the prostate (the organ with intensive metabolism of steroids) and inducible expression of the brain: [26]. CYP3A4 through competitive binding to the same set of response elements (everted repeats 63 is also found in the testes, liver, ER6; kidirect repeats DR3neys, placenta, and DR4)pancreas [5,6,8,9,14,20,21]. PXR,

2. Mechanisms of CYP3A Regulation

2.1. Constitutive Regulation of CYP3A4 Transcription

CAR,onstitutive or VDR unbound byregulation of aCYP3A4 ligtrand is located in the cytoplasm as a complex with heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) or cytoplasmic constitutive active/androstane receptor retentionscription, both positive and negative, is mediated by hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α (HNF4α) and other hepatic transcription factors, including HNF1α and HNF3γ [27-31], CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (CCRP). When activated by a ligand, each of them formss alpha and beta (C/EBPα and C/EBPβ), and upstream transcription factor 1 (USF1) [10,32] via binding to three major cis-acting heterodimer with retinoid X receptor α (RXRα), relocates to the nucleus, binds to a modules: constitutive liver enhancer module 4 (CLEM4) (positions −11.4 to −10.5 kbp), the distal xenobiotic-response element, recrive enhancer module (XREM) (−7.2 to −7.8 kbp) and the proximal promoter (prP) [10].

When bouitsnd coactivators, and activateto DNA, HNF4α attracts CYP3A4 transcription. Estrogen receptor (ER) and glucocorticoid receptor (GR) raise CYP3A4 expression by enhancingcoactivators and other accessory proteins and positively regulates the expression of CAR, RXRα, and PXR. Ligand-activated farnesoid X receptor (FXR) uptarget genes. In the liver, HNF4α is located exclusively in the nucleus and regulates small heterodimer partner (SHP), which prevents the recruitment of coactivators to chromatin and/or forms heterodimers with RXRα, thereby inhibitithe constitutive expression of a large number of target genes, including CYP3A4 [33].

2.2. Regulation of CYP3A4 Transcription

CYP3A4 expression. Histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) inhibition by carbamazepine downregulates CYP3A4. Liver X is modulated by various mechanisms involving nuclear receptor (LXR) forms a heterodimers, hormones, xenobiotics, and signaling molecules. CYP3A4 with RXRα that then binds to DR4 in the target gene, thus repressing its expression. After the binding of a ligand to LXR or Rs regulated by a large number of xenobiotics, including many drugs, endogenous compounds, and many hormones, such as triiodothyronine, dexamethasone, and growth hormone [34].

XR,enobiotic- the heterodimer changes its conformation, which leads to a release of corepressors and the recruitment of coactivators. This event causes transcription of a target gene (and endobiotic-mediated CYP3A4 induction is indirect and entails activation of such ligand-dependent nuclear receptors as PXR, CAR, VDR, glucocorticoid receptor (GR) α, estrogen receptor (ER) α, bile acid receptor (farnesoid X receptor; FXR), oxysterol receptor (liver X receptor; LXR), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha; PPARα(PPARα) [10, its protein product binds as a PPARα–RXRα heterodime11,14,35-50] as well as by binding to the three major cis-actoing motifs DR1 and DR2 dules: CLEM4, distal XREM, and prPXRE [10].

Nucleandr enhances the transcripreceptors participating in the regulation of CYP3A4 shandre protein PXR.partners, Lligand-activated PXR suppresses PPARα-dependens, DNA-sensing elements, and target gene expression by inhibiting peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1α) recruitments, thereby forming a complex regulatory network by which the cell adapts to changes in its chemical environment [9,14].

2.3. Negative Regulation of CYP3A Enzymes

Suppression Hypoxiaf CYP3A agend inflammation inducees is mediated by the activityation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and promote a release of the cytokines that increase the [51]. In addition, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) attenuates PXR-mediated transcription of CCAAT enhancer-binding protein beta (C/EBPβ) anal activation induced theby translation rifampicin in vitrof C/EBPβ-LIP mRNA [51,52]. C/EBPβ-LIP competes with C/EBPαroteins p53, NF-κB, and C/EBPβ-LAP for binding to response elements-LIP are involved in the promoterrepression of CYP3A4, thus lowering its expressiongene activity [9]. NF-κB activates miR-155, which directly targets mRNAs of suppressors of cytokine signaling proteins (especiallyion plays an important role in the suppressorion of cCYP3A genes by disruptokine signaling 1: SOCS1) thereby inhibiting obligatory negative feedback ing the binding of the PXR–RXRα complex to DNA [53]. Cytokine-mediated downregulation of CYP3A4 during the inflammatory responses. Abbreviations.via C/EBPβ-LAP:the a C/EBPβ isoform called liver-enricheJanus kinase (JAK)–signal transducer and activator protein; C/EBPβ-LIP: a C/EBPβ isoform called liver-enriched inhibitory of transcription (STAT) pathway is of great importance [10].

2.4. An Additional Level of Regulation of CYP3A Genes

2.4.1. Epigenetic Mechanisms of CYP3A Gene Regulation

Exprotein; COUP-TFI: chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcriptionssion of CYP genes is influenced by epigenetic factor I; COUP-TFII: chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor II; DR1, DR2, DR3, DR4, and ER6: s including histone modifications, DNA methylation, and regulation by noncoding RNAs [54].

2.4.2. Genetic Polymorphisms of CYP3A Genes and Their Influence on the Activity of CYP3A Enzymes

AG(G/T)TCA-like direct repeats separated by 1, 2, 3, or 4 bases, respectively, and an inverted repeat separated by 6 bases; ERE: ER-responsive element; FXRE: FXR-responsive element, GRE: GR-responsive element; HIF-1α: hypoxia-inducible factor 1-α; HNF-4α-AS1: hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α-antisense-RNA 1; IL-2, -4, or -6: interleukin 2, 4 or 6; INFγ: interferon γ; PHD2: prolyl hydroxylase domain-containing protein 2; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; TRα1: thyroid hormone receptor-α1; TRβ1: thyroid hormone receptor-β1.

Thuthough members of the CYP3A subfamily share high identity of amino acid and DNA sequences, their tissue- and age-specific expression patterns and substrate specificity differ considerably [55]. Genetic polymorphisms are a major cause of inter-individual differences, mostin CYP3A inducers act through transcriptional actexpression and function [3,56].

2.4.3. CYP3A Inducers

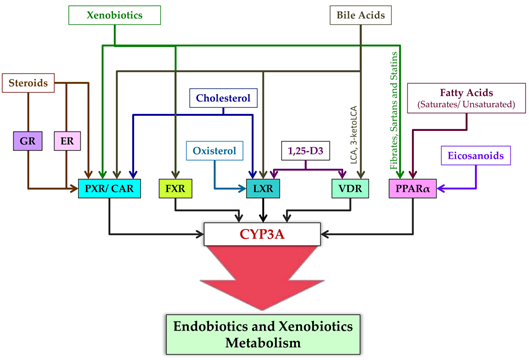

Livgationnds [9][11][13]. CYP3A isoforms and nnuclear receptors involved in their regulation are subject (as part of post-transcriptional regulation) to ubiquitination (CYP3A4 modulating CYP3A expression are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Ligands CYP3A5) and phosphorylation (CYP3A4 and PXR) [11], whof nuclear receptors modulating CYP3A expreas post-translational regulation of ssion.

2.4.4. CYP3A Inhibitors

CYP3A enzymes consists of thme stabilization of CYP3A mRNAs and proteinstabolize a variety [6][11].

Molecularf mechanisms of induction may differcompounds among the four major humanwhich CYP3A genes and almong their polymorphic variants owing to differences in their structure, and the mechanisms can also differ among different tissues, possibly because of different ratios of crucial protein factors. This complexity is a consequencest the only common feature is lipophilicity and relatively large size; therefore, it is not surprising that many of the wide range of CYP3A ligands and of nuclear receptors mediating the inductionse compounds act as inhibitors of CYP3A genzymes [9][13][57].

3. Involvement of CYP3A Enzymes in Biological Processes

CYP3A enzymes have very broad substrate specificity and metabolize a wide range of compounds in terms of chemical and biological properties. They catalyze reactions of hydroxylation, N-demethylation, O-dealkylation, S-oxidation, deamination, and epoxidation [35] [23] of endogenous and exogenous compounds. CYP3A perform physiological functions by taking part in such endogenous processes as steroid catabolism, bile acid metabolism, and lipid and vitamin D metabolism. CYP3A enzymes metabolize a wide variety of therapeutics and may play an important role in alterations of biological activities of drugs or in enhanced clearance of drugs as well as in drug interactions. For instance, CYP3A enzymes’ substrates are such endogenous compounds as hormones, cholesterol, bile acids, arachidonic acid, and vitamin D as well as the vast majority of drugs and of xenobiotics that are not pharmaceuticals [11][12][13][11,12,14].

4. CYP3A Involvement in Pathological Processes

3.1. Metabolism of Endogenous Compounds

3.1.1. Biotransformation of Cholesterol and Bile Acids by CYP3A Enzymes

CYP3A enzymes are involved in cholestasis is a pathologerol and bile acid metabolic pathways [58-60]. Cholesterol is metabolized to 4β-hydroxycholesterol [13] and to 25-hydroxycholesterol by CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 [13,61].

CYP3A enzymes participal condition where normal flowte in bile acid biotransformation [58-60]. CYP3A enzymes are associated with a minor pathway for the biosynthesis of primary cholate of bile is low or disturbed, and bile acids accumulate in thacids. 25-Hydroxylation of 5β-cholestan-3α,7α,12α-triol, which is an intermediate in the biosynthesis of cholic acid, is catalyzed by CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 [62].

3.1.2. Biotransformation of Hormones by CYP3A Enzymes

CYP3A enzymes liver. Stimulation ofplay an important part in hormonal homeostasis. With regard to steroid hormones, the CYP3A4 activity in cholestasis may be an effective subfamily plays an important role in the metabolism of androgens (testosterone, androstenedione, dehydroepiandrosterone, and dihydrotestosterone), progesterone, cortisol, and their metabolites [10,12,14].

3.1.3. Biotransformation of Vitamin D by the CYP3A Subfamily

In the liverapeutic approach to such diseases [19] and small intestine, CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 are involved in vitamin D metabolism [22].

3.1.4. Biotransformation of Arachidonic Acid by CYP3A Enzymes

Arachidonic acid is metabolites known as eicosanoithe precursor to various physiologically active molecules such as epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs), whoseich emergence depends on CYP3A-are a class of functionally bioactive lipid mediated meors derived from the metabolism, are implicated in the pathophysiology of various diseases. For example, of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids under the action of multiple enzymes of three main families, including cyclooxygenases, lipoxygenases, and cytochromes P450 [63,64].

3.2. Biotransformation of Exogenous Compounds

The substherates of CYP3A4 epoxygenase, res enzymes are a wide range of prescription drugs as well as xenobiotics such as carcinogens benzo[a]pyrene, 7,8-dihydrondiol, and atlatoxin B [65,66].

CYP3A enzymesi can metable for the production of EETs, is overexpressed in breast cancer and is linked with olize many structurally and functionally distinct classes of drugs [34,67-77]. The involvement of CYP3A enzymes in the metabolism of most drugs underlies their main biomedical significance as enzymes that influence drug kinetics and as participants in drug interactions.

3.3. Endogenous and Exogenous Biomarkers of Activity of CYP3A Enzymes

Accurathe initiation and progression of breast cancerpredictions of the activity of CYP3A enzymes are needed to provide effective pharmacotherapy to predict treatment outcomes or potential adverse [36].effects of Invarious human hepatomtherapeutic agents and to assess the development and progression of diseases.

Resea rcell line Hep3B, overexpressionh is underway for identifying optimal endogenous biomarkers of the activity of CYP3A4 also promotes cell growth and cell cycle transition from the G1 to S phase enzymes, e.g., derivatives of cholesterol, of bile acids, or of steroid hormones, which can be quantified by measuring the concentration of certain compounds in a urine or blood sample without the introduction of xenobiotics into the human body [78]. Appropriate combinations of such markers [37].

Tshould make role oit possible to predict the activity of CYP3A enzymes in the mwhile taking into account contributions of different isoforms [11].

4. CYP3A Involvement in Pathological Processes

4.1. Diseases Related to the Participation of CYP3A Enzymes in Bile Acid Metabolism

Cholestabolism of sex steroid hormones implies an association with the development of hormone-depesis is a pathological condition where normal flow of bile is low or disturbed, and bile acids accumulate in the liver. The reason is either mechanical obstruction of bile ducts or defects in hepatic transporters [79]. The outcome is inflammation and damage to the bile ducts, followed by exposure of hepatocytes to high concentrations of bile acids, which can result in hepatocyte death [79,80]. For control over processes in the gastrointestinal tract in cholestatic conditions, the composition of bile acids and the size of their pool are important, and hydrophobic bile acids are especially cytotoxic [80,81].

Stimulationd of CYP3A4 activity in cholestasis may bent an effective therapeutic approach to such diseases [34].

New Itherapeut has long been known that CYP3A enzymes are expressed in nic approaches are being developed for the treatment of cholestatic pathologies, including agonists of FXR, which mediates the induction of CYP3A4 expression by bile acids [82]. Furthermore, other derivatives of natural bile acids have been proposed: “bile mimetics,” such as nor-ursodeoxycholic acid and obeticholic acid, which is a potent FXR agonist [83].

4.2. Diseases Associated with the Participation of CYP3A Enzymes in Arachidonic Acid Metabolism

Arachidornic acid mal and tetabolites known as eicosanoids (EETs), a sumbclass of orous tissues of the brexylipins, have a wide range of physiological effects in cardiovascular homeostasis and regulation of cell growth, inflammation, and immune responses. EETs function as regulators [38][39][40] of cardiac, vascular [84-87], and renal physiof the prostatelogy [88-90]. In the cardiovascular system, EETs serve as [41][42],vascular relaxatin cells of the endometrium on factors independent of nitric oxide and prostacyclin I2 [91].

Eicosanoid s (EETs), whose emergence dervixpends on CYP3A-mediated [43][44]metabolism, anre implicated in ovaria the pathophysiology of various diseases.

4.3. Roles of CYP3A Enzymes in Diseases Associated with the CYP3A Involvement in the Metabolism of Sex Steroids

The role of CYP3A enzymes tumorin the metabolism of sex steroid hormones [45]implies an association with the development of hormone-dependent diseases.

4.4. Diseases Related to the Participation of CYP3A Enzymes in Vitamin D Metabolism

Vitamin D has multiple effects on the biological processes that regulate the metabolism of calcium and phosphorus and also affects proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis of cells as well as immune regulation [46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53].

CYP3A4, by taking part in the inactivation of an active vitamin D metabolite [1.25(ОН)2D3], may have a significant impact on circulating vitamin D levels [54][55]and hence calcium homeostasis, which in turn may influence bone and immune-system health [92,93] by downregulating the overexpression of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1α, IL-1β, and TNF [94,95].

It is possible that the progression of cardiovascular diseases may be due to the inactivating effect of CYP3A4 on the active form of vitamin D because a low concentration of 1,25(OH)2D3 in blood serum is strongly associated with the initiation of cardiovascular diseases [96] and with the incidence of arterial hypertension [97].

4.5. Changes in the Expression and Activity of CYP3A Enzymes in Various Pathological Conditions

It is now clear that the expression and activity of CYP enzymes are affected by such pathological conditions as infection, inflammation, and cancer [10,98,99].

4.5.1. Inflammation-Dependent Changes in the Expression and Activity of CYP3A Enzymes

The influence of inflammation on the expression of CYP3A enzymes is are affected by such pathological conditions as in important topic because an alteration of these enzymatic activities leads to a change in pharmacokinetics of prescription drugs. Inflammation is a common sign of many diseases and is implicated in the pathogenesis of such illnesses as infectious diseases, cancer, diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease as well as age-related processes such as normal aging and metabolic aberrations [100]. Sources of inflammation are infections, e.g., hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, and COVID-19 [101]. Aside from infections, other possible sources of inflammation in the human body are diseases of organs (the kidneys, liver, lungs, and heart), diabetes mellitus, autoimmune diseases (ankylosing spondylitis, psoriasis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Crohn’s disease, and celiac disease), and cancer. Additionally, possible sources of inflammation are vaccination, a surgical procedure, a critical condition of a patient, and treatment with immunomodulatory agents, anti-TNF antibodies, or monoclonal antibodies [101].

In such disease states, the regulation ofection, inf CYP enzymes is connected with inflammation status [100]. It is recognized that changes related to CYP enzymes are a common consequence of the immunostimulation following infection and inflammation [102,103]. The source of modulation of CYP enzymes’ activities is endogenous inflammation, and cancer markers: cytokines, adipokines, lipid metabolites of nitric oxide, proteases, and reactive oxygen species [104]. Inflammation is accompanied by suppression of the CYP enzymes that metabolize xenobiotics, including medical drugs [105]. The most studied CYP subfamily [10][56][57]in inflammation is CYP3A [101].

4.5.2. Aberrant Intratumoral Expression of CYP3A Enzymes

The main clinical consequences of aberrant intratumoral expression of CYP3A4 may be mediated by administration of anticancer drugs that are CYP3A substrates during the treatment of Ewing’s sarcoma. Local expression of CYP3A enzymes in malignant tissue may contribute to the development of multidrug resistance or toxicity observed in this type of tumor.

Recent investigation into the aberrant expression of CYP3A5 in cancer, depending on the malignancy and ability to metastasize, uncovered a role of CYP3A5 in cancer progression, metastasis, and invasion.

5. Concluding Remarks

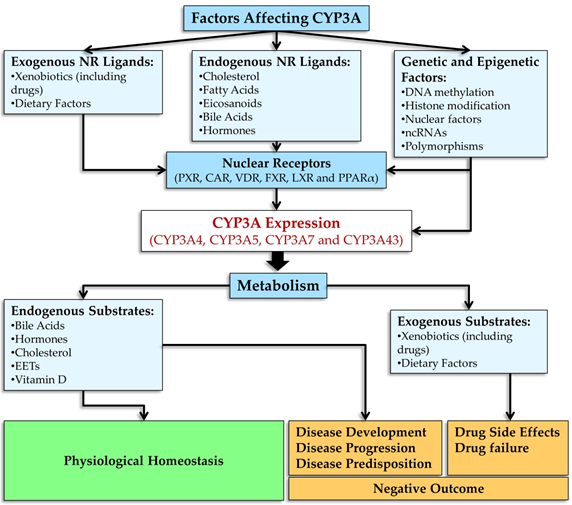

This resviearchw is aimed at highlighting the main roles of CYP3A enzymes along with their unique characteristics in the metabolism of biologically active endogenous compounds and numerous xenobiotics that are important in clinical pharmacology as well as the involvement of these enzymes in a wide range of physiological and pathological phenomena. The scientific literature cited in this researchview attests to remarkable efforts and advances in the understanding how the CYP3A family of phase I biotransformation enzymes is integrated into the vast and complex network of physiological processes detoxifying endo- and xenobiotics. The function of CYP3A enzymes is complex because the effects of activation their genes are determined by a wide range of endogenous and exogenous ligands and by a unique regulatory system that involves CYP3A enzymes in many physiological and pathological processes in cells and tissues of the body (Figure 25).

Figure 25. Effects of CYP3A enzymes on the metabolism of endo- and xenobiotics have an influence on a wide range of physiological and pathophysiological processes in the body.

The totality of evidence indicates that the activation of CYP3A genes can be either beneficial or detrimental during diseases of various organs and tissues. The ultimate effects depend both on the context of a disease and on the nature of ligands of the nuclear receptors that control CYP3A genes’ transcription.

Currently, the molecular mechanisms by which CYP3A enzymes take part in pathogenesis are well understood only for a few diseases; in particular, a role of CYP3A5 in carcinogenesis has been demonstrated. There are more reports of (i) diseases associated with the participation of CYP3A enzymes in the metabolism of endogenous compounds and (ii) pathological conditions affecting the expression and activity of CYP3A enzymes. The consequence of an alteration of these enzymes’ activities is a change in the pharmacokinetics of the drugs used for treatment. Much basic research has been conducted on the role of CYP3A enzymes in pathological processes, but clinical studies that are aimed at influencing the mechanisms of signaling pathways regulating CYP3A genes in various diseases are still insufficient, and further investigation is needed.

References

- Guengerich, F.P. Mechanisms of Cytochrome P450-Catalyzed Oxidations. ACS Catal 2018, 8, 10964-10976, doi:10.1021/acscatal.8b03401.

- Annalora, A.J.; Marcus, C.B.; Iversen, P.L. Alternative Splicing in the Cytochrome P450 Superfamily Expands Protein Diversity to Augment Gene Function and Redirect Human Drug Metabolism. Drug Metab Dispos 2017, 45, 375-389, doi:10.1124/dmd.116.073254.

- Waring, R.H. Cytochrome P450: genotype to phenotype. Xenobiotica 2020, 50, 9-18, doi:10.1080/00498254.2019.1648911.

- Tracy, T.S.; Chaudhry, A.S.; Prasad, B.; Thummel, K.E.; Schuetz, E.G.; Zhong, X.B.; Tien, Y.C.; Jeong, H.; Pan, X.; Shireman, L.M.; et al. Interindividual Variability in Cytochrome P450-Mediated Drug Metabolism. Drug Metab Dispos 2016, 44, 343-351, doi:10.1124/dmd.115.067900.

- Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, X.; Dong, X.; Zhi, L.; Jin, L.; He, F. Molecular population genetics of human CYP3A locus: signatures of positive selection and implications for evolutionary environmental medicine. Environ Health Perspect 2009, 117, 1541-1548, doi:10.1289/ehp.0800528.

- Gibson, G.G.; Plant, N.J.; Swales, K.E.; Ayrton, A.; El-Sankary, W. Receptor-dependent transcriptional activation of cytochrome P4503A genes: induction mechanisms, species differences and interindividual variation in man. Xenobiotica 2002, 32, 165-206, doi:10.1080/00498250110102674.

- Nebert, D.W.; Wikvall, K.; Miller, W.L. Human cytochromes P450 in health and disease. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2013, 368, 20120431, doi:10.1098/rstb.2012.0431.

- Daly, A.K. Significance of the minor cytochrome P450 3A isoforms. Clin Pharmacokinet 2006, 45, 13-31, doi:10.2165/00003088-200645010-00002.

- Raunio, H.; Hakkola, J.; Pelkonen, O. Regulation of CYP3A genes in the human respiratory tract. Chem Biol Interact 2005, 151, 53-62, doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2003.12.007.

- Zanger, U.M.; Schwab, M. Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacol Ther 2013, 138, 103-141, doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.12.007.

- Fujino, C.; Sanoh, S.; Katsura, T. Variation in Expression of Cytochrome P450 3A Isoforms and Toxicological Effects: Endo- and Exogenous Substances as Regulatory Factors and Substrates. Biol Pharm Bull 2021, 44, 1617-1634, doi:10.1248/bpb.b21-00332.

- Burk, O.; Wojnowski, L. Cytochrome P450 3A and their regulation. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2004, 369, 105-124, doi:10.1007/s00210-003-0815-3.

- Penzak, S.R.; Rojas-Fernandez, C. 4beta-Hydroxycholesterol as an Endogenous Biomarker for CYP3A Activity: Literature Review and Critical Evaluation. J Clin Pharmacol 2019, 59, 611-624, doi:10.1002/jcph.1391.

- Qin, X.; Wang, X. Role of vitamin D receptor in the regulation of CYP3A gene expression. Acta Pharm Sin B 2019, 9, 1087-1098, doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2019.03.005.

- Tsujimoto, M.; Horie, M.; Honda, H.; Takara, K.; Nishiguchi, K. The structure-activity correlation on the inhibitory effects of flavonoids on cytochrome P450 3A activity. Biol Pharm Bull 2009, 32, 671-676, doi:10.1248/bpb.32.671.

- Fujita, K. Food-drug interactions via human cytochrome P450 3A (CYP3A). Drug Metabol Drug Interact 2004, 20, 195-217, doi:10.1515/dmdi.2004.20.4.195.

- Chen, S.; Wang, K.; Wan, Y.J. Retinoids activate RXR/CAR-mediated pathway and induce CYP3A. Biochem Pharmacol 2010, 79, 270-276, doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2009.08.012.

- Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Klaunig, J.E. Modulation of xenobiotic nuclear receptors in high-fat diet induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Toxicology 2018, 410, 199-213, doi:10.1016/j.tox.2018.08.007.

- Finta, C.; Zaphiropoulos, P.G. Intergenic mRNA molecules resulting from trans-splicing. J Biol Chem 2002, 277, 5882-5890, doi:10.1074/jbc.M109175200.

- Gellner, K.; Eiselt, R.; Hustert, E.; Arnold, H.; Koch, I.; Haberl, M.; Deglmann, C.J.; Burk, O.; Buntefuss, D.; Escher, S.; et al. Genomic organization of the human CYP3A locus: identification of a new, inducible CYP3A gene. Pharmacogenetics 2001, 11, 111-121, doi:10.1097/00008571-200103000-00002.

- Domanski, T.L.; Finta, C.; Halpert, J.R.; Zaphiropoulos, P.G. cDNA cloning and initial characterization of CYP3A43, a novel human cytochrome P450. Mol Pharmacol 2001, 59, 386-392, doi:10.1124/mol.59.2.386.

- Nem, D.; Baranyai, D.; Qiu, H.; Godtel-Armbrust, U.; Nestler, S.; Wojnowski, L. Pregnane X receptor and yin yang 1 contribute to the differential tissue expression and induction of CYP3A5 and CYP3A4. PLoS One 2012, 7, e30895, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030895.

- Ince, I.; Knibbe, C.A.; Danhof, M.; de Wildt, S.N. Developmental changes in the expression and function of cytochrome P450 3A isoforms: evidence from in vitro and in vivo investigations. Clin Pharmacokinet 2013, 52, 333-345, doi:10.1007/s40262-013-0041-1.

- Ohtsuki, S.; Schaefer, O.; Kawakami, H.; Inoue, T.; Liehner, S.; Saito, A.; Ishiguro, N.; Kishimoto, W.; Ludwig-Schwellinger, E.; Ebner, T.; et al. Simultaneous absolute protein quantification of transporters, cytochromes P450, and UDP-glucuronosyltransferases as a novel approach for the characterization of individual human liver: comparison with mRNA levels and activities. Drug Metab Dispos 2012, 40, 83-92, doi:10.1124/dmd.111.042259.

- Sevrioukova, I.F. Structural Basis for the Diminished Ligand Binding and Catalytic Ability of Human Fetal-Specific CYP3A7. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, doi:10.3390/ijms22115831.

- Wilson, R.T.; Masters, L.D.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S.; Salzberg, A.C.; Hartman, T.J. Ancestry-Adjusted Vitamin D Metabolite Concentrations in Association With Cytochrome P450 3A Polymorphisms. Am J Epidemiol 2018, 187, 754-766, doi:10.1093/aje/kwx187.

- Biggs, J.S.; Wan, J.; Cutler, N.S.; Hakkola, J.; Uusimaki, P.; Raunio, H.; Yost, G.S. Transcription factor binding to a putative double E-box motif represses CYP3A4 expression in human lung cells. Mol Pharmacol 2007, 72, 514-525, doi:10.1124/mol.106.033795.

- Jover, R.; Moya, M.; Gomez-Lechon, M.J. Transcriptional regulation of cytochrome p450 genes by the nuclear receptor hepatocyte nuclear factor 4-alpha. Curr Drug Metab 2009, 10, 508-519, doi:10.2174/138920009788898000.

- Tirona, R.G.; Lee, W.; Leake, B.F.; Lan, L.B.; Cline, C.B.; Lamba, V.; Parviz, F.; Duncan, S.A.; Inoue, Y.; Gonzalez, F.J.; et al. The orphan nuclear receptor HNF4alpha determines PXR- and CAR-mediated xenobiotic induction of CYP3A4. Nat Med 2003, 9, 220-224, doi:10.1038/nm815.

- Tegude, H.; Schnabel, A.; Zanger, U.M.; Klein, K.; Eichelbaum, M.; Burk, O. Molecular mechanism of basal CYP3A4 regulation by hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha: evidence for direct regulation in the intestine. Drug Metab Dispos 2007, 35, 946-954, doi:10.1124/dmd.106.013565.

- Rodriguez-Antona, C.; Bort, R.; Jover, R.; Tindberg, N.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M.; Gomez-Lechon, M.J.; Castell, J.V. Transcriptional regulation of human CYP3A4 basal expression by CCAAT enhancer-binding protein alpha and hepatocyte nuclear factor-3 gamma. Mol Pharmacol 2003, 63, 1180-1189, doi:10.1124/mol.63.5.1180.

- Martinez-Jimenez, C.P.; Gomez-Lechon, M.J.; Castell, J.V.; Jover, R. Transcriptional regulation of the human hepatic CYP3A4: identification of a new distal enhancer region responsive to CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta isoforms (liver activating protein and liver inhibitory protein). Mol Pharmacol 2005, 67, 2088-2101, doi:10.1124/mol.104.008169.

- Gonzalez, F.J. Regulation of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha-mediated transcription. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 2008, 23, 2-7, doi:10.2133/dmpk.23.2.

- Chen, J.; Zhao, K.N.; Chen, C. The role of CYP3A4 in the biotransformation of bile acids and therapeutic implication for cholestasis. Ann Transl Med 2014, 2, 7, doi:10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2013.03.02.

- Quattrochi, L.C.; Guzelian, P.S. Cyp3A regulation: from pharmacology to nuclear receptors. Drug Metab Dispos 2001, 29, 615-622.

- Achour, B.; Barber, J.; Rostami-Hodjegan, A. Expression of hepatic drug-metabolizing cytochrome p450 enzymes and their intercorrelations: a meta-analysis. Drug Metab Dispos 2014, 42, 1349-1356, doi:10.1124/dmd.114.058834.

- Goodwin, B.; Hodgson, E.; Liddle, C. The orphan human pregnane X receptor mediates the transcriptional activation of CYP3A4 by rifampicin through a distal enhancer module. Mol Pharmacol 1999, 56, 1329-1339, doi:10.1124/mol.56.6.1329.

- Goodwin, B.; Hodgson, E.; D'Costa, D.J.; Robertson, G.R.; Liddle, C. Transcriptional regulation of the human CYP3A4 gene by the constitutive androstane receptor. Mol Pharmacol 2002, 62, 359-365, doi:10.1124/mol.62.2.359.

- Jover, R.; Bort, R.; Gomez-Lechon, M.J.; Castell, J.V. Cytochrome P450 regulation by hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 in human hepatocytes: a study using adenovirus-mediated antisense targeting. Hepatology 2001, 33, 668-675, doi:10.1053/jhep.2001.22176.

- Thomas, M.; Burk, O.; Klumpp, B.; Kandel, B.A.; Damm, G.; Weiss, T.S.; Klein, K.; Schwab, M.; Zanger, U.M. Direct transcriptional regulation of human hepatic cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha). Mol Pharmacol 2013, 83, 709-718, doi:10.1124/mol.112.082503.

- Pascussi, J.M.; Drocourt, L.; Gerbal-Chaloin, S.; Fabre, J.M.; Maurel, P.; Vilarem, M.J. Dual effect of dexamethasone on CYP3A4 gene expression in human hepatocytes. Sequential role of glucocorticoid receptor and pregnane X receptor. Eur J Biochem 2001, 268, 6346-6358, doi:10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02540.x.

- Duniec-Dmuchowski, Z.; Ellis, E.; Strom, S.C.; Kocarek, T.A. Regulation of CYP3A4 and CYP2B6 expression by liver X receptor agonists. Biochem Pharmacol 2007, 74, 1535-1540, doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2007.07.040.

- Wang, D.; Lu, R.; Rempala, G.; Sadee, W. Ligand-Free Estrogen Receptor alpha (ESR1) as Master Regulator for the Expression of CYP3A4 and Other Cytochrome P450 Enzymes in the Human Liver. Mol Pharmacol 2019, 96, 430-440, doi:10.1124/mol.119.116897.

- Carazo, A.; Hyrsova, L.; Dusek, J.; Chodounska, H.; Horvatova, A.; Berka, K.; Bazgier, V.; Gan-Schreier, H.; Chamulitrat, W.; Kudova, E.; et al. Acetylated deoxycholic (DCA) and cholic (CA) acids are potent ligands of pregnane X (PXR) receptor. Toxicol Lett 2017, 265, 86-96, doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2016.11.013.

- Gnerre, C.; Blattler, S.; Kaufmann, M.R.; Looser, R.; Meyer, U.A. Regulation of CYP3A4 by the bile acid receptor FXR: evidence for functional binding sites in the CYP3A4 gene. Pharmacogenetics 2004, 14, 635-645, doi:10.1097/00008571-200410000-00001.

- Adachi, R.; Honma, Y.; Masuno, H.; Kawana, K.; Shimomura, I.; Yamada, S.; Makishima, M. Selective activation of vitamin D receptor by lithocholic acid acetate, a bile acid derivative. J Lipid Res 2005, 46, 46-57, doi:10.1194/jlr.M400294-JLR200.

- Pascussi, J.M.; Gerbal-Chaloin, S.; Duret, C.; Daujat-Chavanieu, M.; Vilarem, M.J.; Maurel, P. The tangle of nuclear receptors that controls xenobiotic metabolism and transport: crosstalk and consequences. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2008, 48, 1-32, doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105349.

- Matsubara, T.; Yoshinari, K.; Aoyama, K.; Sugawara, M.; Sekiya, Y.; Nagata, K.; Yamazoe, Y. Role of vitamin D receptor in the lithocholic acid-mediated CYP3A induction in vitro and in vivo. Drug Metab Dispos 2008, 36, 2058-2063, doi:10.1124/dmd.108.021501.

- Schroder, A.; Wollnik, J.; Wrzodek, C.; Drager, A.; Bonin, M.; Burk, O.; Thomas, M.; Thasler, W.E.; Zanger, U.M.; Zell, A. Inferring statin-induced gene regulatory relationships in primary human hepatocytes. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2473-2477, doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btr416.

- Rakhshandehroo, M.; Hooiveld, G.; Muller, M.; Kersten, S. Comparative analysis of gene regulation by the transcription factor PPARalpha between mouse and human. PLoS One 2009, 4, e6796, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006796.

- Gu, X.; Ke, S.; Liu, D.; Sheng, T.; Thomas, P.E.; Rabson, A.B.; Gallo, M.A.; Xie, W.; Tian, Y. Role of NF-kappaB in regulation of PXR-mediated gene expression: a mechanism for the suppression of cytochrome P-450 3A4 by proinflammatory agents. J Biol Chem 2006, 281, 17882-17889, doi:10.1074/jbc.M601302200.

- Okamura, M.; Shizu, R.; Hosaka, T.; Sasaki, T.; Yoshinari, K. Possible involvement of the competition for the transcriptional coactivator glucocorticoid receptor-interacting protein 1 in the inflammatory signal-dependent suppression of PXR-mediated CYP3A induction in vitro. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 2019, 34, 272-279, doi:10.1016/j.dmpk.2019.04.005.

- Li, Y.; Lin, N.; Ji, X.; Mai, J.; Li, Q. Organotin compound DBDCT induces CYP3A suppression through NF-kappaB-mediated repression of PXR activity. Metallomics 2019, 11, 936-948, doi:10.1039/c8mt00361k.

- Li, D.; Tolleson, W.H.; Yu, D.; Chen, S.; Guo, L.; Xiao, W.; Tong, W.; Ning, B. Regulation of cytochrome P450 expression by microRNAs and long noncoding RNAs: Epigenetic mechanisms in environmental toxicology and carcinogenesis. J Environ Sci Health C Environ Carcinog Ecotoxicol Rev 2019, 37, 180-214, doi:10.1080/10590501.2019.1639481.

- Giebel, N.L.; Shadley, J.D.; McCarver, D.G.; Dorko, K.; Gramignoli, R.; Strom, S.C.; Yan, K.; Simpson, P.M.; Hines, R.N. Role of Chromatin Structural Changes in Regulating Human CYP3A Ontogeny. Drug Metab Dispos 2016, 44, 1027-1037, doi:10.1124/dmd.116.069344.

- Wang, D.; Guo, Y.; Wrighton, S.A.; Cooke, G.E.; Sadee, W. Intronic polymorphism in CYP3A4 affects hepatic expression and response to statin drugs. Pharmacogenomics J 2011, 11, 274-286, doi:10.1038/tpj.2010.28.

- Lewis, D.F.; Eddershaw, P.J.; Goldfarb, P.S.; Tarbit, M.H. Molecular modelling of CYP3A4 from an alignment with CYP102: identification of key interactions between putative active site residues and CYP3A-specific chemicals. Xenobiotica 1996, 26, 1067-1086, doi:10.3109/00498259609167423.

- Hayes, M.A.; Li, X.Q.; Gronberg, G.; Diczfalusy, U.; Andersson, T.B. CYP3A Specifically Catalyzes 1beta-Hydroxylation of Deoxycholic Acid: Characterization and Enzymatic Synthesis of a Potential Novel Urinary Biomarker for CYP3A Activity. Drug Metab Dispos 2016, 44, 1480-1489, doi:10.1124/dmd.116.070805.

- Lin, Q.; Tan, X.; Wang, W.; Zeng, W.; Gui, L.; Su, M.; Liu, C.; Jia, W.; Xu, L.; Lan, K. Species Differences of Bile Acid Redox Metabolism: Tertiary Oxidation of Deoxycholate is Conserved in Preclinical Animals. Drug Metab Dispos 2020, 48, 499-507, doi:10.1124/dmd.120.090464.

- Zhang, J.; Gao, L.Z.; Chen, Y.J.; Zhu, P.P.; Yin, S.S.; Su, M.M.; Ni, Y.; Miao, J.; Wu, W.L.; Chen, H.; et al. Continuum of Host-Gut Microbial Co-metabolism: Host CYP3A4/3A7 are Responsible for Tertiary Oxidations of Deoxycholate Species. Drug Metab Dispos 2019, 47, 283-294, doi:10.1124/dmd.118.085670.

- Nitta, S.I.; Hashimoto, M.; Kazuki, Y.; Takehara, S.; Suzuki, H.; Oshimura, M.; Akita, H.; Chiba, K.; Kobayashi, K. Evaluation of 4beta-Hydroxycholesterol and 25-Hydroxycholesterol as Endogenous Biomarkers of CYP3A4: Study with CYP3A-Humanized Mice. AAPS J 2018, 20, 61, doi:10.1208/s12248-018-0186-9.

- Furster, C.; Wikvall, K. Identification of CYP3A4 as the major enzyme responsible for 25-hydroxylation of 5beta-cholestane-3alpha,7alpha,12alpha-triol in human liver microsomes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1999, 1437, 46-52, doi:10.1016/s0005-2760(98)00175-1.

- Snider, N.T.; Kornilov, A.M.; Kent, U.M.; Hollenberg, P.F. Anandamide metabolism by human liver and kidney microsomal cytochrome p450 enzymes to form hydroxyeicosatetraenoic and epoxyeicosatrienoic acid ethanolamides. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2007, 321, 590-597, doi:10.1124/jpet.107.119321.

- Colombero, C.; Cardenas, S.; Venara, M.; Martin, A.; Pennisi, P.; Barontini, M.; Nowicki, S. Cytochrome 450 metabolites of arachidonic acid (20-HETE, 11,12-EET and 14,15-EET) promote pheochromocytoma cell growth and tumor associated angiogenesis. Biochimie 2020, 171-172, 147-157, doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2020.02.014.

- Wolf K.K., P.M.F. Metabolic Barrier of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Comprehensive Toxicology (Third Edition) 2018, 3, 74-98, doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-801238-3.95671-X.

- Deng, J.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, N.Y.; Karrow, N.A.; Krumm, C.S.; Qi, D.S.; Sun, L.H. Aflatoxin B1 metabolism: Regulation by phase I and II metabolizing enzymes and chemoprotective agents. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res 2018, 778, 79-89, doi:10.1016/j.mrrev.2018.10.002.

- Klees, T.M.; Sheffels, P.; Dale, O.; Kharasch, E.D. Metabolism of alfentanil by cytochrome p4503a (cyp3a) enzymes. Drug Metab Dispos 2005, 33, 303-311, doi:10.1124/dmd.104.002709.

- Zhou, X.J.; Zhou-Pan, X.R.; Gauthier, T.; Placidi, M.; Maurel, P.; Rahmani, R. Human liver microsomal cytochrome P450 3A isozymes mediated vindesine biotransformation. Metabolic drug interactions. Biochem Pharmacol 1993, 45, 853-861, doi:10.1016/0006-2952(93)90169-w.

- Preissner, S.; Kroll, K.; Dunkel, M.; Senger, C.; Goldsobel, G.; Kuzman, D.; Guenther, S.; Winnenburg, R.; Schroeder, M.; Preissner, R. SuperCYP: a comprehensive database on Cytochrome P450 enzymes including a tool for analysis of CYP-drug interactions. Nucleic Acids Res 2010, 38, D237-243, doi:10.1093/nar/gkp970.

- Spratlin, J.; Sawyer, M.B. Pharmacogenetics of paclitaxel metabolism. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2007, 61, 222-229, doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.09.006.

- Royer, I.; Monsarrat, B.; Sonnier, M.; Wright, M.; Cresteil, T. Metabolism of docetaxel by human cytochromes P450: interactions with paclitaxel and other antineoplastic drugs. Cancer Res 1996, 56, 58-65.

- Harris, J.W.; Katki, A.; Anderson, L.W.; Chmurny, G.N.; Paukstelis, J.V.; Collins, J.M. Isolation, structural determination, and biological activity of 6 alpha-hydroxytaxol, the principal human metabolite of taxol. J Med Chem 1994, 37, 706-709, doi:10.1021/jm00031a022.

- Baker, S.D.; Sparreboom, A.; Verweij, J. Clinical pharmacokinetics of docetaxel : recent developments. Clin Pharmacokinet 2006, 45, 235-252, doi:10.2165/00003088-200645030-00002.

- Tang, S.C.; Kort, A.; Cheung, K.L.; Rosing, H.; Fukami, T.; Durmus, S.; Wagenaar, E.; Hendrikx, J.J.; Nakajima, M.; van Vlijmen, B.J.; et al. P-glycoprotein, CYP3A, and Plasma Carboxylesterase Determine Brain Disposition and Oral Availability of the Novel Taxane Cabazitaxel (Jevtana) in Mice. Mol Pharm 2015, 12, 3714-3723, doi:10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00470.

- Duckett, D.R.; Cameron, M.D. Metabolism considerations for kinase inhibitors in cancer treatment. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2010, 6, 1175-1193, doi:10.1517/17425255.2010.506873.

- Ling, J.; Johnson, K.A.; Miao, Z.; Rakhit, A.; Pantze, M.P.; Hamilton, M.; Lum, B.L.; Prakash, C. Metabolism and excretion of erlotinib, a small molecule inhibitor of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase, in healthy male volunteers. Drug Metab Dispos 2006, 34, 420-426, doi:10.1124/dmd.105.007765.

- Pophali, P.A.; Patnaik, M.M. The Role of New Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer J 2016, 22, 40-50, doi:10.1097/PPO.0000000000000165.

- Magliocco, G.; Thomas, A.; Desmeules, J.; Daali, Y. Phenotyping of Human CYP450 Enzymes by Endobiotics: Current Knowledge and Methodological Approaches. Clin Pharmacokinet 2019, 58, 1373-1391, doi:10.1007/s40262-019-00783-z.

- Evangelakos, I.; Heeren, J.; Verkade, E.; Kuipers, F. Role of bile acids in inflammatory liver diseases. Semin Immunopathol 2021, 43, 577-590, doi:10.1007/s00281-021-00869-6.

- Zollner, G.; Trauner, M. Mechanisms of cholestasis. Clin Liver Dis 2008, 12, 1-26, vii, doi:10.1016/j.cld.2007.11.010.

- Chiang, J.Y.L. Bile acid metabolism and signaling in liver disease and therapy. Liver Res 2017, 1, 3-9, doi:10.1016/j.livres.2017.05.001.

- Garcia, M.; Thirouard, L.; Sedes, L.; Monrose, M.; Holota, H.; Caira, F.; Volle, D.H.; Beaudoin, C. Nuclear Receptor Metabolism of Bile Acids and Xenobiotics: A Coordinated Detoxification System with Impact on Health and Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19, doi:10.3390/ijms19113630.

- Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; Loomba, R.; Sanyal, A.J.; Lavine, J.E.; Van Natta, M.L.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Chalasani, N.; Dasarathy, S.; Diehl, A.M.; Hameed, B.; et al. Farnesoid X nuclear receptor ligand obeticholic acid for non-cirrhotic, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (FLINT): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2015, 385, 956-965, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61933-4.

- Fleming, I. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, cell signaling and angiogenesis. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 2007, 82, 60-67, doi:10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2006.05.003.

- Fleming, I. Vascular cytochrome p450 enzymes: physiology and pathophysiology. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2008, 18, 20-25, doi:10.1016/j.tcm.2007.11.002.

- Fleming, I. The cytochrome P450 pathway in angiogenesis and endothelial cell biology. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2011, 30, 541-555, doi:10.1007/s10555-011-9302-3.

- Fleming, I. The factor in EDHF: Cytochrome P450 derived lipid mediators and vascular signaling. Vascul Pharmacol 2016, 86, 31-40, doi:10.1016/j.vph.2016.03.001.

- Imig, J.D. Epoxide hydrolase and epoxygenase metabolites as therapeutic targets for renal diseases. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2005, 289, F496-503, doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00350.2004.

- Capdevila, J.; Wang, W. Role of cytochrome P450 epoxygenase in regulating renal membrane transport and hypertension. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2013, 22, 163-169, doi:10.1097/MNH.0b013e32835d911e.

- Capdevila, J.H.; Wang, W.; Falck, J.R. Arachidonic acid monooxygenase: Genetic and biochemical approaches to physiological/pathophysiological relevance. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 2015, 120, 40-49, doi:10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2015.05.004.

- Xu, X.; Zhang, X.A.; Wang, D.W. The roles of CYP450 epoxygenases and metabolites, epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, in cardiovascular and malignant diseases. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2011, 63, 597-609, doi:10.1016/j.addr.2011.03.006.

- Khazai, N.; Judd, S.E.; Tangpricha, V. Calcium and vitamin D: skeletal and extraskeletal health. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2008, 10, 110-117, doi:10.1007/s11926-008-0020-y.

- Fleet, J.C. The role of vitamin D in the endocrinology controlling calcium homeostasis. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2017, 453, 36-45, doi:10.1016/j.mce.2017.04.008.

- Hughes, D.A.; Norton, R. Vitamin D and respiratory health. Clin Exp Immunol 2009, 158, 20-25, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.04001.x.

- Kumar, V.; Kancharla, S.; Jena, M.K. In silico virtual screening-based study of nutraceuticals predicts the therapeutic potentials of folic acid and its derivatives against COVID-19. Virusdisease 2021, 32, 29-37, doi:10.1007/s13337-020-00643-6.

- Lavie, C.J.; Dinicolantonio, J.J.; Milani, R.V.; O'Keefe, J.H. Vitamin D and cardiovascular health. Circulation 2013, 128, 2404-2406, doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002902.

- Ferder, M.; Inserra, F.; Manucha, W.; Ferder, L. The world pandemic of vitamin D deficiency could possibly be explained by cellular inflammatory response activity induced by the renin-angiotensin system. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2013, 304, C1027-1039, doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00403.2011.

- Morgan, E.T. Impact of infectious and inflammatory disease on cytochrome P450-mediated drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2009, 85, 434-438, doi:10.1038/clpt.2008.302.

- Morgan, E.T. In Drug Metabolism in Diseases, Xie, W., Ed.; Academic Press: Boston, 2017; pp. 21-58.

- Wu, K.C.; Lin, C.J. The regulation of drug-metabolizing enzymes and membrane transporters by inflammation: Evidences in inflammatory diseases and age-related disorders. J Food Drug Anal 2019, 27, 48-59, doi:10.1016/j.jfda.2018.11.005.

- Lenoir, C.; Rollason, V.; Desmeules, J.A.; Samer, C.F. Influence of Inflammation on Cytochromes P450 Activity in Adults: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 733935, doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.733935.

- Rendic, S.; Guengerich, F.P. Update information on drug metabolism systems--2009, part II: summary of information on the effects of diseases and environmental factors on human cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes and transporters. Curr Drug Metab 2010, 11, 4-84, doi:10.2174/138920010791110917.

- Christensen, H.; Hermann, M. Immunological response as a source to variability in drug metabolism and transport. Front Pharmacol 2012, 3, 8, doi:10.3389/fphar.2012.00008.

- de Jong, L.M.; Jiskoot, W.; Swen, J.J.; Manson, M.L. Distinct Effects of Inflammation on Cytochrome P450 Regulation and Drug Metabolism: Lessons from Experimental Models and a Potential Role for Pharmacogenetics. Genes (Basel) 2020, 11, doi:10.3390/genes11121509.

- Yanev, S.G. Immune system drug metabolism interactions: toxicological insight. Adipobiology 2014, 6, 31-36.