The International Space Station program is tied together by a complex set of legal, political and financial agreements between the fifteen nations involved in the project, governing ownership of the various components, rights to crewing and utilization, and responsibilities for crew rotation and resupply of the International Space Station. These agreements tie together the five space agencies and their respective International Space Station programs and govern how they interact with each other on a daily basis to maintain station operations, from traffic control of spacecraft to and from the station, to utilization of space and crew time. In March 2010, the International Space Station Program Managers from each of the five partner agencies were presented with Aviation Week's Laureate Award in the Space category, and NASA's International Space Station Program was awarded the 2009 Collier Trophy.

- utilization

- traffic control

- crewing

1. Legal Aspects

1.1. 1998 Agreement

The legal structure that regulates the station is multi-layered. The primary layer establishing obligations and rights between the ISS partners is the Space Station Intergovernmental Agreement (IGA), an international treaty signed on January 28, 1998 by fifteen governments involved in the Space Station project. The ISS consists of Canada, Japan, the Russian Federation, the United States, and eleven Member States of the European Space Agency (Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom).[1] Article 1 outlines its purpose:

This Agreement is a long term international co-operative framework on the basis of genuine partnership, for the detailed design, development, operation, and utilization of a permanently inhabited civil Space Station for peaceful purposes, in accordance with international law.[2]

The IGA sets the stage for a second layer of agreements between the partners referred to as 'Memoranda of Understanding' (MOUs), of which four exist between NASA and each of the four other partners. There are no MOUs between ESA, Roskosmos, CSA and JAXA because NASA is the designated manager of the ISS. The MOUs are used to describe the roles and responsibilities of the partners in more detail.

A third layer consists of bartered contractual agreements or the trading of the partners' rights and duties, including the 2005 commercial framework agreement between NASA and Roskosmos that sets forth the terms and conditions under which NASA purchases seats on Soyuz crew transporters and cargo capacity on unmanned Progress transporters.

A fourth legal layer of agreements implements and supplements the four MOUs further. Notably among them is the ISS code of conduct, setting out criminal jurisdiction, anti-harassment and certain other behavior rules for ISS crewmembers.[3] made in 1998.

1.2. Utilization

There is no fixed percentage of ownership for the whole space station. Rather, Article 5 of the IGA sets forth that each partner shall retain jurisdiction and control over the elements it registers and over personnel in or on the Space Station who are its nationals.[2] Therefore, for each ISS module only one partner retains sole ownership. Still, the agreements to use the space station facilities are more complex.

The station is composed of two sides: Russian Orbital Segment (ROS) and U.S. Orbital Segment (USOS).[4]

- Russian Orbital Segment (mostly Russian ownership, except the Zarya module)

- Zarya: first component of the Space Station, USSR/Russia-built, U.S. funded (hence U.S.-owned)

- Zvezda: the functional center of the Russian portion, living quarters, Russia-owned

- Pirs: airlock, docking, Russia-owned

- Poisk: redundancy for Pirs, Russia-owned

- Rassvet: storage, docking, Russia-owned

- U.S. Orbital Segment (mixed U.S. and international ownership)

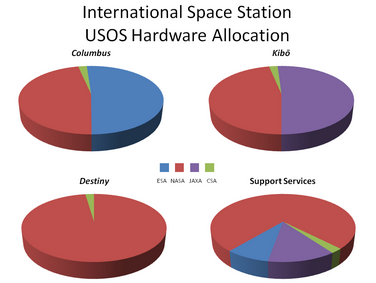

- Columbus: 51% for ESA, 46.7% for NASA and 2.3% for CSA.[5]

- Kibō: 51% for JAXA, 46.7% for NASA and 2.3% for CSA.[6]

- Destiny: 97.7% for NASA and 2.3% for CSA.[7]

- Crew time, electrical power and rights to purchase supporting services (such as data upload & download and communications) are divided 76.6% for NASA, 12.8% for JAXA, 8.3% for ESA, and 2.3% for CSA.[5][6][7]

2. Program Operations

2.1. Expeditions

Long-duration flights to the International Space Station are broken into expeditions. Expeditions have an average duration of half a year, and they commence following the official handover of the station from one Expedition commander to another. Expeditions 1 through 6 consisted of three-person crews, but the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster led to a reduction to two crew members for Expeditions 7 to 12. Expedition 13 saw the restoration of the station crew to three. While only three crew members are permanently on the station, several expeditions, such as Expedition 16, have consisted of up to six astronauts or cosmonauts. Only 3 members were active at any given time, one of the 'seats' was rotated out during separate flights.[8][9]

STS-115 expanded of the living volume and capabilities of the station so that it could host a crew of six. Expedition 20 was the first ISS crew of this size. Expedition 20's crew was lifted to the station in two separate Soyuz-TMA flights launched at two different times (each Soyuz-TMA can hold only three people): Soyuz TMA-14 on 26 March 2009 and Soyuz TMA-15 on 27 May 2009. However, the station would not be permanently occupied by six crew members all year. For example, when the Expedition 20 crew (Roman Romanenko, Frank De Winne and Bob Thirsk) returned to Earth in November 2009, for a period of about two weeks only two crew members (Jeff Williams and Max Surayev) were aboard. This increased to five in early December, when Oleg Kotov, Timothy Creamer and Soichi Noguchi arrived on Soyuz TMA-17. It decreased to three when Williams and Surayev departed in March 2010, and finally returned to six in April 2010 with the arrival of Soyuz TMA-18, carrying Aleksandr Skvortsov, Mikhail Korniyenko and Tracy Caldwell Dyson.[8][9]

The International Space Station is the most-visited spacecraft in the history of space flight. (As of October 2015), The ISS has had 220 visitors. Mir had 137 visitors (104 different people).[10]

2.2. Visiting Spacecraft

Spacecraft from four different space agencies visit the ISS, serving a variety of purposes. The Automated Transfer Vehicle from the European Space Agency, the Russian Roskosmos Progress spacecraft and the H-II Transfer Vehicle from the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency have provided resupply services to the station. In addition, Russia supplies a Soyuz spacecraft used for crew rotation and emergency evacuation, which is replaced every six months. Finally, the US serviced the ISS through its Space Shuttle program, providing resupply missions, assembly and logistics flights, and crew rotation until the program was retired in 2011.

SpaceX is the first private company to resupply the ISS.[11]

The availability of docking ports on the station, and traffic from four different agencies and launch sites must be coordinated. Spacecraft launches can see delays while waiting for traffic to clear [12] A particular tight traffic jam occurred during the latch of ESA's Jules Verne Automated Transfer Vehicle in spring 2008. The cargo ship launched 2 day prior to STS-123, and had to wait in a holding orbit performing system tests while waiting for the shuttle to clear the station.[13]

(As of April 2016), there have been 46 Soyuz, 63 Progress, 5 ATV, 5 HTV, 5 Cygnus, 7 Dragon and 37 Space Shuttle flights to the station.[14] Expeditions require, on average, 2,722 kg of supplies, Soyuz crew rotation flights and Progress resupply flights visit the station on average two and three times respectively each year.[15]

2.3. Mission Control Centers

The components of the ISS are operated and monitored by their respective space agencies at control centers across the globe, including:

- NASA's Mission Control Center at Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, serves as the primary control facility for the US segment of the ISS and also controls the Space Shuttle missions that visit the station.[16]

- NASA's Payload Operations and Integration Center at Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, serves as the center that coordinates all payload operations in the US Segment.[16] This center links Earth-bound researchers around the world with their experiments and astronauts aboard the International Space Station.[17]

- Roskosmos's Mission Control Center at Korolyov, Moscow, controls the Russian Orbital Segment of the ISS, in addition to individual Soyuz and Progress missions.[16]

- ESA's Columbus Control Center at the German Aerospace Center (DLR) in Oberpfaffenhofen, Germany, controls the European Columbus research laboratory.[16]

- ESA's ATV Control Center, at the Toulouse Space Centre (CST) in Toulouse, France, controls flights of the unmanned European Automated Transfer Vehicle.[16]

- JAXA's JEM Control Centre and HTV Control Centre at Tsukuba Space Center (TKSC) in Tsukuba, Japan, are responsible for operating the Japanese Experiment Module complex and all flights of the unmanned Japanese H-II Transfer Vehicle respectively.[16]

- CSA's MSS Control at Saint-Hubert, Quebec, Canada, controls and monitors the Mobile Servicing System, or Canadarm2.[16]

3. Commercial Orbital Transportation Services

On January 18, 2006 NASA announced Commercial Orbital Transportation Services programme.[18] NASA has suggested that "Commercial services to ISS will be necessary through at least 2015."[19] Instead of flying payloads to ISS on government-operated vehicles, NASA would spend $500 million (less than the cost of a single Space Shuttle flight) through 2010 to finance the demonstration of orbital transportation services from commercial providers.

COTS must be distinguished from the related Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) program. COTS relates to the development of the vehicles, CRS to the actual deliveries. COTS involves a number of Space Act Agreements, with NASA providing milestone-based payments.

On December 23, 2008, NASA entered into CRS contracts with Orbital Sciences and SpaceX to utilize their COTS cargo vehicles—Cygnus and Dragon, respectively—for cargo delivery to the International Space Station.

4. Constellation Program

Constellation Program, a human spaceflight program, was developed by NASA. On February 1, 2010, President Barack Obama announced a proposal to cancel the program effective with the U.S. 2011 fiscal year budget,[20][21][22][23] but later announced changes to the proposal in a major space policy speech at Kennedy Space Center on April 15, 2010, which including reviving the Orion spacecraft for use as a rescue spacecraft for ISS.

5. Future of the ISS

Former NASA Administrator Michael D. Griffin says the International Space Station has a role to play as NASA moves forward with a new focus for the manned space programme, which is to go out beyond Earth orbit for purposes of human exploration and scientific discovery. "The International Space Station is now a stepping stone on the way, rather than being the end of the line," Griffin said.[24] Griffin has said that station crews will not only continue to learn how to live and work in space, but also will learn how to build hardware that can survive and function for the years required to make the round-trip voyage from Earth to Mars.[24]

Despite this view, however, in an internal e-mail leaked to the press on 18 August 2008 from Griffin to NASA managers,[25][26][27] Griffin apparently communicated his belief that the current US administration had made no viable plan for US crews to participate in the ISS beyond 2011, and that the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) were actually seeking its demise.[26] The e-mail appeared to suggest that Griffin believed the only reasonable solution was to extend the operation of the space shuttle beyond 2010, but noted that Executive Policy (i.e. the White House) was firm that there would be no extension of the space shuttle retirement date, and thus no US capability to launch crews into orbit until the Dragon 2 becomes operational in 2020, at the earliest.[26] He did not see purchase of Russian launches for NASA crews as politically viable following the 2008 South Ossetia war, and hoped the incoming Barack Obama administration would resolve the issue in 2009 by extending space shuttle operations beyond 2010.

A solicitation issued by NASA JSC indicates NASA's intent to purchase from Roscosmos "a minimum of 3 Soyuz seats up to a maximum of 24 seats beginning in the Spring of 2012" to provide ISS crew transportation.[28][29]

On 7 September 2008, NASA released a statement regarding the leaked email, in which Griffin said:

The leaked internal email fails to provide the contextual framework for my remarks, and my support for the administration's policies. Administration policy is to retire the shuttle in 2010 and purchase crew transport from Russia until Ares and Orion are available. The administration continues to support our request for an INKSNA exemption. Administration policy continues to be that we will take no action to preclude continued operation of the International Space Station past 2016. I strongly support these administration policies, as do OSTP and OMB.—Michael D. Griffin[30]

On 15 October 2008, President Bush signed the NASA Authorization Act of 2008, giving NASA funding for one additional mission to "deliver science experiments to the station".[31][32][33][34] The Act allows for an additional space shuttle flight, STS-134, to the ISS to install the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, which was previously cancelled.[35]

President Barack Obama has supported the continued operation of the station, and supported the NASA Authorization Act of 2008.[35] Obama's plan for space exploration includes finishing the station and completion of the US programmes related to the Orion spacecraft.[36]

According to the Outer Space Treaty, the United States and Russia are legally responsible for all modules they have launched.[37] Natural orbital decay with random reentry (as with Skylab), boosting the station to a higher altitude (which would delay reentry), and a controlled targeted de-orbit to a remote ocean area were considered as ISS disposal options.[38] As of late 2010, the preferred plan is to use a slightly modified Progress spacecraft to de-orbit the ISS.[39] This plan was seen as the simplest, cheapest and with the highest margin.[39]

The Orbital Piloted Assembly and Experiment Complex (OPSEK) was previously intended to be constructed of modules from the Russian Orbital Segment after the ISS is decommissioned. The modules under consideration for removal from the current ISS included the Multipurpose Laboratory Module (Nauka), currently scheduled to be launched in November 2019, and the other new Russian modules that are planned to be attached to Nauka. These newly launched modules would still be well within their useful lives in 2020 or 2024.[40]

At the end of 2011, the Exploration Gateway Platform concept also proposed using leftover USOS hardware and 'Zvezda 2' [sic] as a refuelling depot and service station located at one of the Earth-Moon Lagrange points. However, the entire USOS was not designed for disassembly and will be discarded.[41]

In February 2015, Roscosmos announced that it would remain a part of the ISS programme until 2024.[42] Nine months earlier—in response to US sanctions against Russia over the annexation of Crimea—Russian Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin had stated that Russia would reject a US request to prolong the orbiting station's use beyond 2020, and would only supply rocket engines to the US for non-military satellite launches.[43]

On 28 March 2015, Russian sources announced that Roscosmos and NASA had agreed to collaborate on the development of a replacement for the current ISS.[44][45] Igor Komarov, the head of Russia's Roscosmos, made the announcement with NASA administrator Charles Bolden at his side.[46] In a statement provided to SpaceNews on 28 March, NASA spokesman David Weaver said the agency appreciated the Russian commitment to extending the ISS, but did not confirm any plans for a future space station.[47]

On 30 September 2015, Boeing's contract with NASA as prime contractor for the ISS was extended to 30 September 2020. Part of Boeing's services under the contract will relate to extending the station's primary structural hardware past 2020 to the end of 2028.[48]

Regarding extending the ISS, on 15 November 2016 General Director Vladimir Solntsev of RSC Energia stated "Maybe the ISS will receive continued resources. Today we discussed the possibility of using the station until 2028," with discussion to continue under the new presidential administration.[49][50] There have also been suggestions that the station could be converted to commercial operations after it is retired by government entities.[51]

In July 2018, the Space Frontier Act of 2018 was intended to extend operations of the ISS to 2030. This bill was unanimously approved in the Senate, but failed to pass in the U.S. House.[52][53] In September 2018, the Leading Human Spaceflight Act was introduced with the intent to extend operations of the ISS to 2030, and was confirmed in December 2018.[54][55][56]

5.1. New Partners

China has reportedly expressed interest in the project, especially if it would be able to work with the RKA. Due to national security concerns, the United States Congress passed a law prohibiting contact between US and Chinese space programs.[57] (As of 2019), China is not involved in the International Space Station.[58] In addition to national security concerns, United States objections include China's human rights record and issues surrounding technology transfer.[59][60] The heads of both the South Korean and Indian space agencies announced at the first plenary session of the 2009 International Astronautical Congress on 12 October that their nations intend to join the ISS program. The talks began in 2010, and were not successful. The heads of agency also expressed support for extending ISS lifetime.[61] European countries not a part of the International Space Station program will be allowed access to the station in a three-year trial period, ESA officials say.[62] The Indian Space Research Organisation has made it clear that it will not join the ISS and will instead build its own space station.[63]

6. Cost

The ISS has been described as the most expensive single item ever constructed.[64] In 2010 the cost was expected to be $150 billion. This includes NASA's budget of $58.7 billion (inflation-unadjusted) for the station from 1985 to 2015 ($72.4 billion in 2010 dollars), Russia's $12 billion, Europe's $5 billion, Japan's $5 billion, Canada's $2 billion, and the cost of 36 shuttle flights to build the station; estimated at $1.4 billion each, or $50.4 billion in total. Assuming 20,000 person-days of use from 2000 to 2015 by two- to six-person crews, each person-day would cost $7.5 million, less than half the inflation-adjusted $19.6 million ($5.5 million before inflation) per person-day of Skylab.[65]

7. Criticism

The International Space Station has been the target of varied criticism over the years. Critics contend that the time and money spent on the ISS could be better spent on other projects—whether they be robotic spacecraft missions, space exploration, investigations of problems here on Earth, or just tax savings.[66] Some critics, like Robert L. Park, argue that very little scientific research was convincingly planned for the ISS in the first place.[67] They also argue that the primary feature of a space-based laboratory is its microgravity environment, which can usually be studied more cheaply with a "vomit comet".[68]

One of the most ambitious ISS projects to date, the Centrifuge Accommodations Module, has been cancelled due to the prohibitive costs NASA faces in simply completing the ISS. As a result, the research done on the ISS is generally limited to experiments which do not require any specialized apparatus. For example, in the first half of 2007, ISS research dealt primarily with human biological responses to being in space, covering topics like kidney stones, circadian rhythm, and the effects of cosmic rays on the nervous system.[69][70][71]

Other criticsTemplate:Like whom have attacked the ISS on some technical design grounds:

- Jeff Foust argued that the ISS requires too much maintenance, especially by risky, expensive EVAs.[72] The magazine The American Enterprise reports, for instance, that ISS astronauts "now spend 85 percent of their time on construction and maintenance" alone.

- The Astronomical Society of the Pacific has mentioned that its orbit is rather highly inclined, which makes Russian launches cheaper, but US launches more expensive.[73] This was intended as a design point, to encourage Russian involvement with the ISS—and Russian involvement saved the project from abandonment in the wake of the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster—but the choice may have increased the costs of completing the ISS substantially. However, it may not be true since additional delta-v required from launching Kennedy space center (28.45 deg) to ISS station (51.6 deg of Russia) is ~34.5 m/s ( 460 m/s*cos(28.45)*cos(51.6) - 460*cos(51.6) ) which is very small (~0.3% velocity or ~1% payload reduction) compared to 9.5 to 10 km/s required to reach to orbit. Launching at a higher altitude needs a plane change in orbit, going from 51 deg at the launch site to a 28 degree orbit could cost as much as ~3 km/s or more than 60% payload reduction (assuming direction correction at same orbital altitude, 7.67 km/s * 2*sin((51.6-28.8)/2) ).

In response to some of these criticisms, advocates of manned space exploration say that criticism of the ISS project is short-sighted, and that manned space research and exploration have produced billions of dollars' worth of tangible benefits to people on Earth. Jerome Schnee estimated that the indirect economic return from spin-offs of human space exploration has been many times the initial public investment.[74] A review of the claims by the Federation of American Scientists argued that NASA's rate of return from spin-offs is actually "astoundingly bad", except for aeronautics work that has led to aircraft sales.[75]

It is therefore debatable whether the ISS, as distinct from the wider space program, will be a major contributor to society. Some advocates argue that apart from its scientific value, it is an important example of international cooperation.[76] Others claim that the ISS is an asset that, if properly leveraged, could allow more economical manned Lunar and Mars missions.[77] Either way, advocates argue that it misses the point to expect a hard financial return from the ISS; rather, it is intended as part of a general expansion of spaceflight capabilities.

References

- "International Space Station - International Cooperation". https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/cooperation/index.html. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- "International Space Station Legal Framework". International Space Station. European Space Agency. 20 July 2001. http://www.esa.int/esaHS/ESAH7O0VMOC_iss_0.html. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- Farand, Andre. "Astronauts' behaviour onboard the International Space Station: regulatory framework" (pdf). International Space Station. UNESCO. Archived from the original on 13 September 2006. https://web.archive.org/web/20060913194014/http://portal.unesco.org/shs/en/file_download.php/785db0eec4e0cdfc43e1923624154cccFarand.pdf. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- "A Look at the Russian Side of the Space Station". Air&Space Mag. 5 March 2016. http://www.airspacemag.com/space/rare-look-russian-side-space-station-180956244/?no-ist. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- "ISS Intergovernmental Agreement". ESA. April 19, 2009. Archived from the original on June 10, 2009. https://web.archive.org/web/20090610083738/http://www.spaceflight.esa.int/users/index.cfm?act=default.page&level=11&page=1980. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- "Memorandum of Understanding Between the National Aeronautics and Space Administration of the United States of America and the Government of Japan Concerning Cooperation on the Civil International Space Station". NASA. February 24, 1998. Archived from the original on 2009-10-29. https://web.archive.org/web/20091029094939/http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/structure/elements/nasa_japan.html. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- "Memorandum of Understanding Between the National Aeronautics and Space Administration of the United States of America and the Canadian Space Agency Concerning Cooperation on the Civil International Space Station". NASA. January 29, 1998. Archived from the original on 2009-10-29. https://web.archive.org/web/20091029094938/http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/structure/elements/nasa_csa.html. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- "International Space Station Expeditions". NASA. 10 April 2009. Archived from the original on 8 September 2005. https://web.archive.org/web/20050908103956/http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/expeditions/index.html. Retrieved 13 April 2009.

- NASA (2008). "International Space Station". NASA. Archived from the original on 7 September 2005. https://web.archive.org/web/20050907073730/http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/main/index.html. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- David Harland (30 November 2004). The Story of Space Station Mir. New York: Springer-Verlag New York Inc. ISBN 978-0-387-23011-5. https://archive.org/details/storyofspacestat0000harl.

- Garcia, Mark (3 April 2015). "International Space Station Commercial Resupply Launch". http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/living/launch/. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ESA (22 March 2007). "Worldwide testing and ISS traffic push ATV launch to autumn 2007". ESA. http://spaceflight.nasa.gov/station/isstodate.html. Retrieved 11 April 2010.

- Tariq Malik (31 January 2008). "Traffic jam in space: ATV docking under tight schedule". ESA. http://www.esa.int/esaHS/SEMX6KK26DF_iss_0.html. Retrieved 11 April 2010.

- "About the Space Station: Facts and Figures". http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/main/onthestation/facts_and_figures.html.

- "Live listing of spacecraft operations". NASA. 1 December 2009. http://www.esa.int/esaCP/SEMFERS4LZE_Life_0.html. Retrieved 8 December 2009.

- Gary Kitmacher (2006). Reference Guide to the International Space Station. Canada: Apogee Books. pp. 71–80. ISBN 978-1-894959-34-6.

- "NASA - International Space Station: Payload Operations Center". NASA. 23 November 2007. Archived from the original on 28 September 2006. https://web.archive.org/web/20060928220418/http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/science/payload_ops.html. Retrieved 11 April 2010.

- "NASA Seeks Proposals for Crew and Cargo Transportation to Orbit" (Press release). NASA. 2006-01-18. Retrieved 2006-11-21. http://www.spaceref.com/news/viewpr.html?pid=18791

- Space Operations Mission Directorate (2006-08-30). "Human Space Flight Transition Plan". NASA. Archived from the original on 2006-09-28. https://web.archive.org/web/20060928222416/http://www.hq.nasa.gov/osf/tran_plan.pdf.

- Amos, Jonathan (February 1, 2010). "Obama cancels Moon return project". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/8489097.stm. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- "Terminations, Reductions, and Savings" (PDF). Archived from the original on March 5, 2010. https://web.archive.org/web/20100305131136/http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/fy2011/assets/trs.pdf. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- Achenbach, Joel (February 1, 2010). "NASA budget for 2011 eliminates funds for manned lunar missions". Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/01/31/AR2010013101058.html. Retrieved February 1, 2010.

- "Fiscal Year 2011 Budget Estimates". Archived from the original on February 1, 2010. https://web.archive.org/web/20100201191410/http://www.nasa.gov/pdf/420990main_FY_201_%20Budget_Overview_1_Feb_2010.pdf. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- Griffin, Michael (July 18, 2001). "Why Explore Space?". NASA. Archived from the original on August 24, 2007. https://web.archive.org/web/20070824135119/http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/exploration/main/griffin_why_explore.html. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- Malik, Tariq (2008). "NASA Chief Vents Frustration in Leaked E-mail". Space.com (Imaginova Corp). http://www.space.com/news/080907-nasa-griffin-email.html. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- Orlando Sentinel (July 7, 2008). "Internal NASA email from NASA Administrator Griffin". SpaceRef.com. http://www.spaceref.com/news/viewsr.html?pid=29133. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- Griffin, Michael (2008). "Michael Griffin email image" (jpg). Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on December 16, 2008. https://web.archive.org/web/20081216230642/http://blogs.orlandosentinel.com/news_space_thewritestuff/files/GriffinEmail.jpg. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- "PROCUREMENT OF CREW TRANSPORTATION AND RESCUE SERVICES FROM ROSCOSMOS". NASA JSC. http://prod.nais.nasa.gov/cgi-bin/eps/synopsis.cgi?acqid=134686.

- "Modification". NASA JSC. http://prod.nais.nasa.gov/cgi-bin/eps/synopsis.cgi?acqid=134857.

- "Statement of NASA Administrator Michael Griffin on Aug. 18 Email" (Press release). NASA. September 7, 2008. Archived from the original on 2009-10-28. Retrieved 2008-12-11. https://web.archive.org/web/20091028183858/http://www.nasa.gov/home/hqnews/2008/sep/HQ_08220_griffin_statement_email.html

- "To authorize the programs of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.". Library of Congress. 2008. http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/bdquery/z?d110:h.r.06063:. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- Berger, Brian (June 19, 2008). "House Approves Bill for Extra Space Shuttle Flight". Space.com (Imaginova Corp). http://www.space.com/news/080619-house-shuttle-flight-bill.html. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- NASA (September 27, 2008). "House Sends NASA Bill to President's Desk". Spaceref.com. http://www.spaceref.com/news/viewpr.html?pid=26558. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- Matthews, Mark (October 15, 2008). "Bush signs NASA authorization act". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on October 19, 2008. https://web.archive.org/web/20081019025713/http://blogs.orlandosentinel.com/news_space_thewritestuff/2008/10/bush-signs-nasa.html. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- Berger, Brian for Space.com (September 23, 2008). "Obama backs NASA waiver, possible shuttle extension". USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/tech/science/space/2008-09-23-obama-nasa-shuttle_N.htm. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- BarackObama.com (2008). "Barack Obama's Plan For American Leadership in Space". Spaceref.com. http://www.spaceref.com/news/viewsr.html?pid=26647. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- United Nations Treaties and Principles on Outer Space. (PDF). United Nations. New York. 2002. ISBN:92-1-100900-6. Retrieved 8 October 2011. http://www.unoosa.org/pdf/publications/STSPACE11E.pdf

- "Tier 2 EIS for ISS". NASA. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19960053133_1996092350.pdf. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- Suffredini, Michael (October 2010). "ISS End-of-Life Disposal Plan". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/pdf/578543main_asap_eol_plan_2010_101020.pdf. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

- Anatoly Zak (22 May 2009). "Russia 'to save its ISS modules'". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/8064060.stm. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- "DC-1 and MIM-2". Russianspaceweb.com. Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. https://web.archive.org/web/20090210130224/http://www.russianspaceweb.com/iss_dc.html. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- de Selding, Peter B. (25 February 2015). "Russia — and Its Modules — To Part Ways with ISS in 2024". Space News. http://spacenews.com/russia-and-its-modules-to-part-ways-with-iss-in-2024/. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- "Russia to ban US from using Space Station over Ukraine sanctions". The Telegraph. Reuters. 13 May 2014. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/russia/10828964/Russia-to-ban-US-from-using-Space-Station-over-Ukraine-sanctions.html. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- Boren, Zachary Davies (28 March 2015). "Russia and the US will build a new space station together". The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/russia-and-the-us-will-build-a-new-space-station-together-10140890.html.

- "Russia & US agree to build new space station after ISS, work on joint Mars project". RT.com. 28 March 2015. http://rt.com/news/244797-russia-us-new-space-station/.

- "Russia announces plan to build new space station with NASA". Space Daily. Agence France-Presse. 28 March 2015. http://www.spacedaily.com/reports/Russia_announces_plan_to_build_new_space_station_with_NASA_999.html.

- Foust, Jeff (28 March 2015). "NASA Says No Plans for ISS Replacement with Russia". SpaceNews. http://spacenews.com/nasa-says-no-plans-for-iss-replacement-with-russia/.

- Maass, Ryan (30 September 2015). "NASA extends Boeing contract for International Space Station". Space Daily. UPI. http://www.spacedaily.com/reports/NASA_extends_Boeing_contract_for_International_Space_Station_999.html. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- "ISS' Life Span Could Extend Into 2028 – Space Corporation Energia Director". Sputnik. 15 November 2016. https://sputniknews.com/russia/201611151047447591-russia-iss-rsc-lifespan/. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- "Space Cowboys: Moscow to Mull Building Russian Orbital Station in Spring 2017". Sputnik. 16 November 2016. https://sputniknews.com/science/201611161047493600-russia-orbital-station/. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- Grush, Loren (24 January 2018). "Trump administration wants to end NASA funding for the International Space Station by 2025". The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2018/1/24/16930154/nasa-international-space-station-president-trump-budget-request-2025.

- "Commercial space bill dies in the House" (in en-US). 2018-12-22. https://spacenews.com/commercial-space-bill-dies-in-the-house/.

- Cruz, Ted (2018-12-21). "S.3277 - 115th Congress (2017-2018): Space Frontier Act of 2018". https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/3277.

- Nelson, Senator Bill (20 December 2018). "The Senate just passed my bill to help commercial space companies launch more than one rocket a day from Florida! This is an exciting bill that will help create jobs and keep rockets roaring from the Cape. It also extends the International Space Station to 2030!". https://twitter.com/SenBillNelson/status/1075840067569139712.

- Foust, Jeff (27 September 2018). "House joins Senate in push to extend ISS". https://www.spacenews.com/house-joins-senate-in-push-to-extend-iss/. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- Babin, Brian (2018-09-26). "H.R.6910 - 115th Congress (2017-2018): Leading Human Spaceflight Act". https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/6910.

- Jeffrey, Kluger. "The Silly Reason the Chinese Aren't Allowed on the Space Station". TIME USA, LLC. https://time.com/3901419/space-station-no-chinese/. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- Mark, Garcia. "International Cooperation". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/cooperation/index.html. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- "China wants role in space station". Associated Press. CNN. 16 October 2007. Archived from the original on 14 March 2008. https://web.archive.org/web/20080314104006/http://www.cnn.com/2007/TECH/space/10/16/china.space.ap/index.html. Retrieved 20 March 2008.

- James Oberg (26 October 2001). "China takes aim at the space station". NBC News. http://www.nbcnews.com/id/3077826. Retrieved 30 January 2009.

- "South Korea, India to begin ISS partnership talks in 2010". Flight International. October 14, 2009. http://www.flightglobal.com/articles/2009/10/14/333406/south-korea-india-to-begin-iss-partnership-talks-in.html. Retrieved 2009-10-14.

- "EU mulls opening ISS to more countries". http://www.space-travel.com/reports/EU_mulls_opening_ISS_to_more_countries_999.html. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- "India planning to have own space station: ISRO chief". The Economic Times. 2019-06-13. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/science/india-planning-to-have-own-space-station-isro-chief/articleshow/69771669.cms.

- Zidbits (6 November 2010). "What Is The Most Expensive Object Ever Built?". Zidbits.com. http://zidbits.com/?p=19. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- Lafleur, Claude (8 March 2010). "Costs of US piloted programs". The Space Review. http://www.thespacereview.com/article/1579/1. Retrieved 18 February 2012. See author correction in comments.

- Mail & Guardian. "A waste of space". Mail & Guardian. http://www.mg.co.za/article/2006-01-26-a-waste-of-space. Retrieved 2009-03-15.

- Park, Bob. "Space Station: Maybe They Could Use It to Test Missile Defense". Archived from the original on 2009-03-22. https://web.archive.org/web/20090322174138/http://bobpark.physics.umd.edu/WN04/wn092404.html. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- Park, Bob. "Space: International Space Station Unfurls New Solar Panels". Archived from the original on 2008-07-04. https://web.archive.org/web/20080704141406/http://bobpark.physics.umd.edu/WN06/wn091506.html. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- NASA (2007). "Renal Stone Risk During Spaceflight: Assessment and Countermeasure Validation (Renal Stone)". NASA. Archived from the original on September 16, 2008. https://web.archive.org/web/20080916102157/http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/science/experiments/Renal-Stone.html. Retrieved November 13, 2007.

- NASA (2007). "Sleep-Wake Actigraphy and Light Exposure During Spaceflight-Long (Sleep-Long)". NASA. Archived from the original on September 16, 2008. https://web.archive.org/web/20080916102107/http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/science/experiments/Sleep-Long.html. Retrieved November 13, 2007.

- NASA (2007). "Anomalous Long Term Effects in Astronauts' Central Nervous System (ALTEA)". NASA. Archived from the original on November 30, 2007. https://web.archive.org/web/20071130072708/http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/science/experiments/ALTEA.html. Retrieved November 13, 2007.

- Jeff Foust (2005). "The trouble with space stations". The Space Review. http://www.thespacereview.com/article/453/1. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- "Up, Up, and Away". Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 1996. http://www.astrosociety.org/education/publications/tnl/34/space2.html. Retrieved September 10, 2006.

- "Economic impact of large public programs The NASA experience". NASA Technical Reports Server (NTRS). 1976. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=640676&id=1&qs=Ntt%3DSchnee%26Ntk%3Dall%26Ntx%3Dmode%2520matchall%26N%3D0%26Ns%3DPublicationYear%257C0. Retrieved November 13, 2007.

- Federation of American Scientists. "NASA Technological Spinoff Fables". Federation of American Scientists. https://fas.org/spp/eprint/jp_950525.htm. Retrieved September 17, 2006.

- Space Today Online (2003). "International Space Station: Human Residency Third Anniversary". Space Today Online. Archived from the original on March 2, 2009. https://web.archive.org/web/20090302091625/http://spacetoday.org/SpcStns/FirstAnnivOccupy.html. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- RSC Energia (2005). "Interview with Niolai (sic) Sevostianov, President, RSC Energia: The mission to Mars is to be international". Mars Today.com/SpaceRef Interactive Inc. Archived from the original on 2013-01-28. https://archive.today/20130128194640/http://www.marstoday.com/news/viewpr.html?pid=18482. Retrieved 2009-03-23.