There is a growing interest among people in western countries for adoption of healthier lifestyle habits and diet behaviors with one of the most known ones to be Mediterranean diet (Med-D). Med-D is linked with daily consumption of food products such as vegetables, fruits, whole grains, seafood, beans, nuts, olive oil, low-fat food derivatives and limited consumption of meat or full fat food products. Med-D is well-known to promote well-being and lower the risk of chronic conditions such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. On the other hand, bioactive constituents in foods may interfere with drugs’ pharmacological mechanisms, modulating the clinical outcome leading to drug-food interactions (DFIs). This reviewtext discusses current evidence for food products that are included within the Med-D and available scientific data suggest a potential contribution in DFIs with impact on therapeutic outcome. Proper patient education and consultation from healthcare providers is important to avoid any conflicts and side effects due to clinically significant DFIs.

- drug-food interactions

- pharmacokinetic interactions

- Mediterranean diet

1. Introduction

2. Mediterranean Food Products and Potential DFIs

2.1. Med-D Food Products

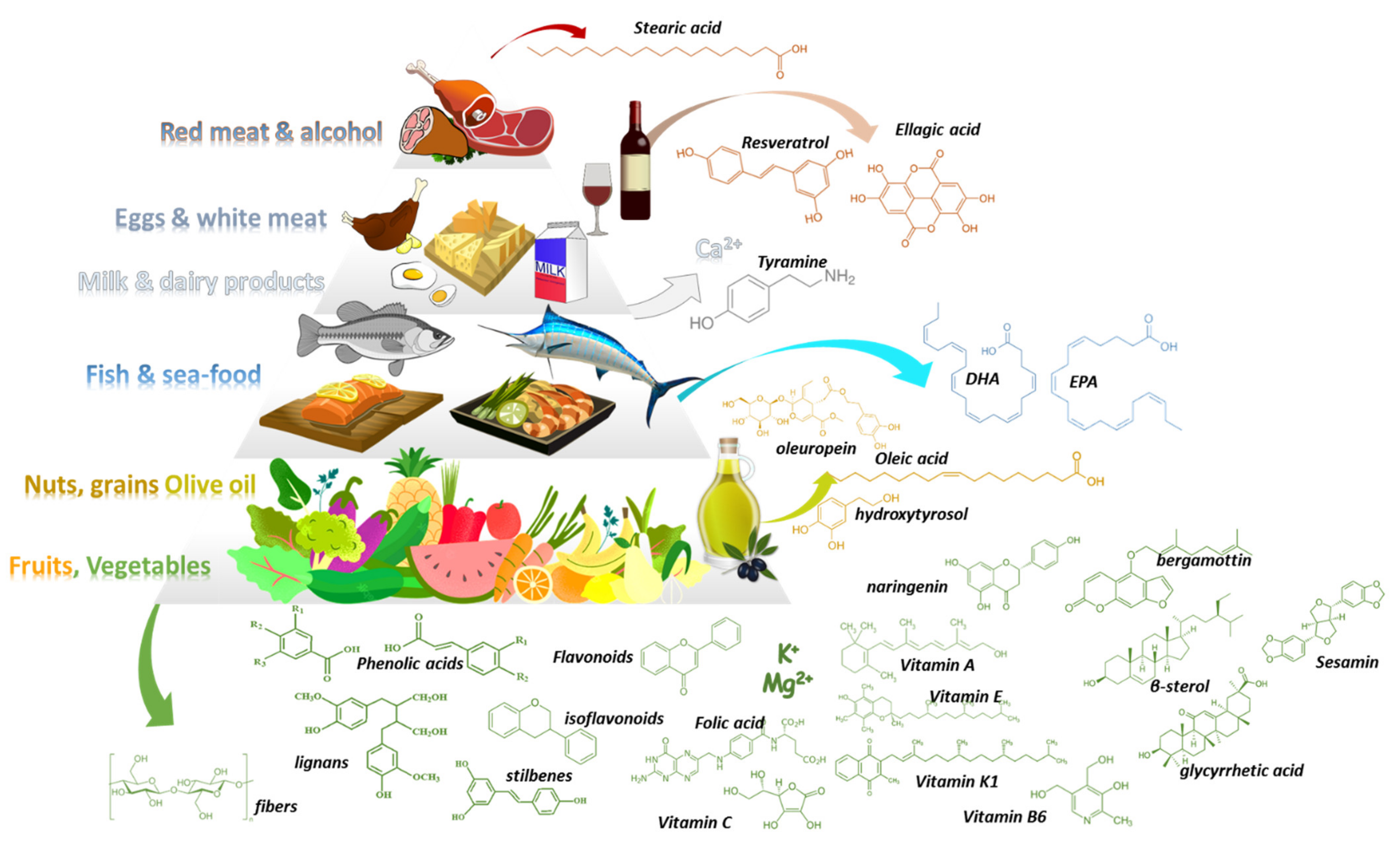

Med-D allows the intake of all types of foods following a general food guidance pyramid (Figure 1) [2,3][2][3]. In its base (level 1) are vegetables, fruits, nuts, and cereals that should be consumed in greater amounts and at daily frequency. Above them (level-2), sea food proteins and omega-3-fatty acids (n-3 FAs) are suggested to be consumed biweekly. Animal food products (level3) such as dairy, cheese, and eggs can be consumed in moderate portions during the week. Red meat (level 4) should be consumed in less proportions during the week along with saturated fat products and sweets. Regarding alcohol, a moderate consumption of wine and other fermented beverages is recommended (one to two glasses with meals). The pyramid is complete considering daily activities and physical exercise. Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 summarize available data regarding potential DFIs for food products of level1 in the Med-D pyramid.

| Food | Type of DFIs | Suggested Mechanism | Clinical Significance | Level of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artichoke | PK | CYP mediated drug metabolism | Moderate | Moderate |

| Low | ||||

| Fruit | Type of DFIs | Suggested Mechanism | Clinical Significance | Level of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apples | PK | OAT transporter inhibition |

| Food | Type of DFIs | Suggested Mechanism | Clinical Significance | Level of Evidence | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate | Good | ||||||||||||

| Barley | PK | Modulation GI absorption | Moderate | Low | |||||||||

| Arugula | Apricots | PD | Anticoagulants—Vitamin K | Moderate | Theoretical | ||||||||

| - | - | - | - | Asparagus | |||||||||

| Buckwheat | - | - | PD | Anticoagulants—Vitamin K | Avocados | PD | Anticoagulants—Vitamin K | Moderate | Theoretical | ||||

| - | - | Moderate | |||||||||||

| Bulgur | Theoretical | ||||||||||||

| - | - | - | - | Beetroots | - | - | Bananas | PD | - | ||||

| Hyperkaliemia, high K | + | Moderate | Theoretical | ||||||||||

| Farro-flax seed | PD | Anticoagulants, n-3 FAs | Moderate | Low | Bell pepper | PD | Anticoagulants—Vitamin K | Millet | - | -Moderate | Cherries | Theoretical | |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | Broccoli | PD | Anticoagulants—Vitamin K | Moderate | Theoretical | |||

| Clementines | PK | CYP mediated drug metabolism | Moderate | Moderate | |||||||||

| Oats & fibers | PK | Modulation GI absorption | ModerateBrussel Sprouts | PK | CYP mediated drug metabolism | Moderate | Moderate | ||||||

| Good | Grapefruit | PK | P-gp transport & CYP mediated drug metabolism | Serious-avoid | High | Cabbage | |||||||

| Polenta | - | - | - | - | PK | CYP mediated drug metabolism | Moderate | Good | |||||

| Grapes | PK | UGT mediated drug metabolism | Moderate | Good | |||||||||

| Rice | - | - | - | - | Carrots | PK | CYP mediated drug metabolism | Minor | Low | ||||

| Lime | PK | ||||||||||||

| Wheat Berries | PK | Modulation GI absorption | Moderate | Low | Cauliflower | PK | CYP mediated drug metabolism | Minor | |||||

| Melons | Moderate | ||||||||||||

| Breads | PD | - | Synergism antidiabetic medications | - | Low | - | Theoretical | - | Celery | PD | Synergism sedatives | Minor | Good |

| Oranges | PK | OAT transporter inhibition | Moderate | Good | Collard greens | PD | Synergism antidiabetic medications | Minor | Low | ||||

| Peaches | PD | Hyperkaliemia, high K+ | Moderate | Theoretical | Cucumbers | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Pears | - | ||||||||||||

| Couscous | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||||||

| Almonds | - | - | - | - | - | ||||||||

| Cashews | PD | Synergism antidiabetic medications | Dandelion greens | PD | Lithium | Moderate | Low | ||||||

| Minor | Low | Pomegranates | PK | CYP mediated drug metabolism | None | High | |||||||

| Chickpeas | Eggplant | - | - | - | - | ||||||||

| Pomelo | PK | P-gp transport & CYP mediated drug metabolism | Use with caution | Good | |||||||||

| Fava beans | PD | Synergism with anti-Parkinson drugs (high L-dopa content) | Moderate | Low | Fennel | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Strawberries | PK/PD | Metabolism & anticoagulation | |||||||||||

| Green peas | - | - | - | - | Fava beans | PD | synergism with anti-parkinson drugs (L-dopa content) | Moderate | Low | ||||

| Hazelnuts | Garlic | PK | |||||||||||

| Kidney beans | PK | Modulation GI absorption | Moderate | MinorGood | |||||||||

| Low | Green beans | - | - | - | - | ||||||||

| Lentils | PD | Hyperkaliemia, high K+ | Minor | Low | Kale | PD | Anticoagulants—Vitamin K | Moderate | Theoretical | ||||

| Peanuts | Leeks | PD | Anticoagulants—Vitamin K | Minor | Theoretical | ||||||||

| Mushrooms | - | - | - | - | |||||||||

| Low | Theoretical | ||||||||||||

| Tangerines | PD | Tyramine pressure effect (MAOIs) | Use with caution | Low | |||||||||

| Pistachios | - | - | - | - | |||||||||

| Sesame seeds (tachini) | PK | CYP mediated metabolism | None | Moderate | Onions | PD | Anticoagulants—Vitamin K | Minor | Theoretical | ||||

| Split peas | PK | Modulation GI absorption | Minor | Theoretical | Potatoes | - | - | ||||||

| Walnuts | PK | - | Modulation GI absorption | - | |||||||||

| Moderate | Theoretical | Radish | PK | stimulate GI motility & transit time | Minor | Moderate | |||||||

| Scallions | PD | Anticoagulants—Vitamin K | Minor | Theoretical | |||||||||

| Shallots | PD | Spinach | PD | Anticoagulants—Vitamin K | Moderate | Theoretical | |||||||

| PK | CYP mediated drug metabolism | Moderate | Moderate | Anticoagulants—Vitamin K | Minor | Theoretical | |||||||

| Squash | PD | stimulant laxative may alter Κ+ | Minor | Theoretical | |||||||||

| Sweet potatoes | - | - | - | - | |||||||||

| Swiss chard | PD | Anticoagulants—Vitamin K | Minor | Theoretical | |||||||||

| Tomatoes | PK | CYP mediated drug metabolism | Minor | Moderate | |||||||||

| Turnips | PD | Synergism antidiabetic medications | Minor | Moderate | |||||||||

| Yams | PD | Synergism with estrogens | Moderate | Good | |||||||||

| Zucchini | - | - | - | - | |||||||||

| Anise | PK | CYP mediated metabolism | Moderate | Good | |||||||||

| Basil | PD | Anticoagulants, n-3 FAs | Moderate | Low | |||||||||

| Bayleaf | PD | Synergism with antidiabetics & sedatives | Minor | Low | |||||||||

| Cinnamon | PD | Synergism antidiabetic & hepatoxicity | Minor | Low | |||||||||

| Cloves | PD | potentiate the effects of drugs that affect hemostasis | Moderate | Moderate | |||||||||

| Cumin | PD | Synergism antidiabetic medications | Moderate | Moderate | |||||||||

| Fennel | - | - | - | - | |||||||||

| Lavender | PD | Synergism with sedatives | Moderate | Low | |||||||||

| Marjoram | PD | Potentiate effects of drugs for hemostasis | Moderate | Low | |||||||||

| Mint | - | - | - | - | |||||||||

| Oregano | PD | Potentiate effects of drugs for hemostasis | Moderate | Low | |||||||||

| Parsley | - | - | - | - | |||||||||

| Pepper | PK | CYP mediated drug metabolism | Minor | Moderate | |||||||||

| Rosemary | - | - | - | - | |||||||||

| Sage | PD | Synergism with sedatives | Moderate | Low | |||||||||

| Savory | PD | Anticoagulants, n-3 FAs | Moderate | Low | |||||||||

| Sumac | PD | Induce nephrotoxicity of drugs | Minor | Low | |||||||||

| Tarragon | PD | Anticoagulants, n-3 FAs | Moderate | Low | |||||||||

| Thyme | PD | Anticoagulants, n-3 FAs | Moderate | ||||||||||

2.2. Drug-Med Diet Interactions

2.2.1. Vegetables, Herbals, Olive Oil, Cereals, and Nuts

The Med-D has its basis in foods of plant-origin with a wide variety of vegetables along with other herbals. It contains an extensive list of domestic and imported vegetables that reached the area through historical trading routes. The most common vegetables include artichokes, arugula, asparagus, beetroots, broccoli, brussel sprouts, cabbage, carrots, celery, collard greens, cucumbers, dandelion greens, eggplant, fennel, garlic leeks, lettuce, mushrooms, mustard greens, onions (all types), peas, peppers, potatoes, pumpkin, radishes, spinach, turnips, zucchini. Case reports and clinical data suggest that potential PK-DFIs can result from consumption of artichoke, broccoli, brussel sprouts, cabbage, cauliflower, and tomatoes [111,112,113][46][47][48]. A pharmacological mechanism can be attributed to the isothiocyanate content (i.e., broccoli, cauliflower etc.) and their capability to modulate drugs’ CYP-mediated metabolism or transport (ABC-transporters) [112][47]. Especially for CYP1A2, it has been shown through clinical trial that brassica vegetables can induce CYP1A2 metabolic activity modulating caffeine’s pharmacokinetics [114][49]. In addition, celery and other apiaceous vegetables (i.e., carrot, celery, dill, cilantro, parsnip, parsley etc.) can decrease cytochrome CYP1A2 activity as has been shown through several studies [112,114][47][49]. Garlic components have shown inhibitory action for CYPs 2C, 2D, and 3A-mediated metabolism in vitro but in a later clinical pharmacokinetic study, long-term use of garlic caplets led to a significant decline in the plasma concentrations of saquinavir which is metabolized from CYP3A4 [115,116][50][51]. Tomato juice was shown in vitro to contain mechanism-based and competitive inhibitor(s) of CYP3A4 [117,118][52][53]. Cabbage and onion juices have also shown potential inhibiting activities on CYP3A4 in vitro [119][54]. Basil demonstrated in vitro potential reversible and time-dependent inhibition of CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 as well as esterase-mediated metabolism of rifampicin, but the concentrations were higher than the ones used in daily food consumption [120][55]. The significance of these potential PK-DFIs is currently unresolved and the level of evidence for most of the cases is low. The frequent consumption of these foods may contribute in an observed inter-individual variability within the treatment goals. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of twenty-three dietary intervention trials in humans analyzed the effect of cruciferous vegetable-enriched diets on drug metabolism. The meta-analyses showed a significant effect on CYP1A2 and glutathione S-transferase-alpha (GSTa) [113][48]. Thus, healthcare advice is needed in case patients habitually consume excessive amounts of vegetables such as broccoli, brussel sprouts, cabbage, cauliflower, radish, and watercress and are under treatment with CYP1A2 substrates (i.e., clozapine, olanzapine, fluvoxamine, haloperidol, melatonin, ramelteon, tizanidine, and theophylline). Regarding PD-DFIs, arugula, asparagus, bell peppers, broccoli, celery, collard greens, kale, onions and leeks, spinach, and chard due to their content of vitamin-K could modulate the INR for people treated with coumadin analogues such as warfarin or acenocoumarol. However, despite this, DFI represents a clinically significant case; it is estimated to be of moderate importance and has a low level of evidence with studies suggesting that a balanced consumption of vegetables does not interfere with INR in a clinically significant way [107,108][56][57]. Concerning other potential PD-DFIs, anise and aniseed’s essential oil (used to enhance the flavor of Greek Ouzo and mastic) in vivo enhanced the effects of CNS drugs (codeine, diazepam, midazolam, pentobarbital, imipramine and fluoxetine) in mice suggesting potential synergism and a clinically significant PD-DFI if it is used in extensive doses [121][58]. Garlic has shown promising data as an antidiabetic agent; thus it may enhance the pharmacologic effect of antidiabetic medicines [122][59]. Turnips have demonstrated synergism with antidiabetic drugs towards hypoglycemia while yams have a good quality of evidence for synergy with estrogens and thus special precautions should be made for patients under estrogen therapy [123,124][60][61]. Naturally occurring levodopa and carbidopa have been quantified in fava beans in fair amounts, thus patients with Parkinson’s under treatment should be aware of possible synergism with co-administered medications [125][62]. Concerning olive oil, its protective role against inflammation-related chronic non-communicable diseases (cardiovascular, diabetes, cancer etc.) have been described thoroughly [126][63]. Proposed mechanisms involve the action of bioactive constituents of olive oil on interleukin-6 (IL-6) and platelet activating factor (PAF) inflammation pathways. In particular, PAF, which is a class of lipid chemical mediators with messenger functions, has gained research attention as a potential drug target due to its involvement in inflammatory diseases such as allergies, asthma, atherosclerosis, diabetes etc. [127][64]. Moreover, it is a point of focus as a contributing biological mechanism for anti-inflammatory action of several food products with protective roles against inflammation [31]. Several bioactive phytochemical compounds such as terpenes and constituents in olive oil with PAF action have been related to protective mechanisms against atherosclerosis [128,129][65][66]. In addition, as of today there is no contribution of olive oil or its constituents in potential DFIs. On the other hand, for some terpenes with PAF action, i.e., cedrol, inhibiting properties against human P450 have been described in vitro and further studies are needed to clarify potential DFIs [130][67]. Regarding potential PD-DFIs of PAF modulators with anti-platelet medications, there are not any reports suggesting potential contribution in DFIs.2.2.2. Fruits and Fruit Juices

The Mediterranean fruits are among the most famous and widely consumed food products globally. Apples, apricots, avocados, cherries, clementines, figs, grapefruits, grapes, melons, nectarines, oranges, peaches, pears, pomegranates, strawberries, tangerines are the most common ones that are consumed by people following the Med-D style. Regarding fruit juices, the fermentable but unfermented product obtained from the edible part of the fruit and preserved fresh, they sometimes contain (due to the extraction process) different constituents or quantities from the original fruit. The most notorious DFI regarding fruits and/or fruit juice with medications is that of grapefruit and its juice (GFJ) [41,131,132,133][41][68][69][70]. GFJ constituents (i.e., furanocoumarins etc.) can inhibit CYP activity (mainly CYP3A) through mechanism-based inhibition as well as transporter proteins in the intestine and liver (i.e., P-gp) [131,133,134,135,136][68][70][71][72][73]. This can elevate drugs’ bioavailability which, along with reduction in drugs’ intrinsic clearance, can result in increased concentrations and potential side effects. Typical examples are the concomitant use of GFJ with: (i) Ca2+ channel antagonists that result in low blood pressure; (ii) HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors that may lead to rhabdomyolysis and renal impairment; and (iii) adverse pulmonary effects caused by amiodarone co-administration [41,70,131,137][41][68][74][75]. Grapefruit as a plant belongs to the plant family of Rutaceae within the genus of Citrus fruits such as lemons, oranges, limes, tangerines fruits that are widely consumed. As a result, the frequent consumption of these products alerted the previous years the scientific community to the need to examine if DFIs could be further observed [138,139,140][76][77][78]. Until today, the most often described mechanism for potential DFIs are related with modulation of the activity of OATP transporters and CYPs metabolic activities [141,142,143][79][80][81]. Citrus fruits such as orange, lemon, pomelo, and lime have been assessed for potential DFIs and compared with GFJ. Pomelo juice increased the bioavailability of cyclosporine in an open-label crossover PK study probably due to inhibition of CYP3A4 and P-gp [144][82]. Orange juice reduced the bioavailability of alendronate and aliskiren [145[83][84],146], whereas Seville orange juice interacts with felodipine in a similar way to GFJ [147][85]. Lime juice has been shown in vivo to increase (similarly to GFJ) the bioavailability and systemic concentrations of carbamazepine with a clinically significant risk for liver and kidney toxicity [148][86]. Although tangerine (fruit and juice) showed some effect in vitro on CYP3A4-mediated metabolism of midazolam, this was of no clinical significance [149][87]. Narirutin found in Citrus fruits has also been observed in vivo to inhibit OATP1A2 and OATP2B1 [150][88]. Regarding apple juice, there is evidence from in vitro, in vivo and clinical studies of inhibiting activity on OATPs and modulation of the PK profile of drugs such as fexofenadine, montelukast and aliskiren [142,143,146,151][80][81][84][89]. It also contributed to a DFI with atenolol in a dose-response relationship but with limited effect on the PD-profile of the drug [152][90]. Cranberry juice and its constituent avicularin inhibited uptake transporters OATP1A2 and AOATP2B1 in vitro [153][91]. In addition, in vitro data indicated inhibition of CYP-mediated metabolism (CYP2C9 and CYP3A4) similar to ketoconazole and fluconazole. The effect is mainly attributed to anthocyanins content but these compounds show poor bioavailability, thus in vitro data were not repeated in vivo or through clinical studies [154,155,156][92][93][94]. Pomegranate juice has demonstrated in vitro/in vivo inhibiting action against CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 but with no clinical impact based on the available clinical data [157][95]. Drug interactions with fruits, fruit juices or pulps can also be related with PD-DFIs, and especially for fruits that contain considerable amounts of potassium (K+). Bananas, apricots, and oranges are some typical examples of high-K+ fruits and in theory their over consumption can be implicated in potential PD-DFIs with ARBs and diuretics [109,110][96][97]. Although this effect is based in theoretical statements, an in vivo study with palm fruits and lisinopril demonstrated elevated serum K+ levels [158][98]. The risk of potential hyperkaliemia is clinically significant, especially in cases of kidney diseases. Although observational studies suggest that adherence to Med-D improves survival for CKD patients, there is a lack of conclusive clinical data regarding DFIs and hyperkaliemia, hence vigilance should be advised from healthcare providers [159,160][99][100].2.2.3. Fish and Sea Food

Fish and sea food (clams, cockles, crabs, groupers, lobsters, mackerel, mussels, octopuses, oysters, salmons, sardines, sea basses, shrimps, squids, sea breams, tunas, etc.) are the main sources of protein and fat within the Med-D diet. They contain high amounts of essential amino acids along with n-3 fatty acids (FA) (i.e., eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid) especially the pelagic fishes (sardines, anchovies, mackerels etc.) [161][101]. Apart of the nutritional value in Med-D, marine n-3 FAs are known to have positive effects on human health such as a protecting role in cardiovascular diseases, inflammation, diabetes, neurocognitive disorders etc. [162][102]. Regarding DFIs, omega-3 FAs seem to reduce coagulation factors (i.e., fibrinogen and prothrombin), thus in theory can potentiate the effects of anticoagulants [163][103]. As of today there have been some case reports of interactions between warfarin co-administration with fish-oil supplements, but the results were not repeated in a retrospective study of a larger cohort of patients with atrial fibrillation and deep vein thrombosis [164,165,166][104][105][106]. Considering also that DS usually have a higher content of n-3 FAs than the consumed food, the potential DFI is of minor importance and negligible for patients that remain adherent in their treatment plan.2.2.4. Milk Dairy Products, White and Red Meat

Milk and dairy products (yoghurt, cheese) are part of the traditional domestic livestock practices around the Mediterranean basin and are part of the historical heritage of the dietary habits for the region. In medicine, milk and dairy products are an old case of potential DFIs due to their content in Ca2+ and tyramine. The presence of Ca2+ in milk and dairy products can create unabsorbed chelate ligands with antibiotic classes of tetracyclines and quinolones resulting in reduced bioavailability (PK-DFIs) [62][107]. Tyramine is a precursor of catecholamines and the inhibition of their metabolism from MAOIs can lead to increased catecholamine levels which can cause hypertension. Tyramine is known to interact with mono-amino oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) resulting in an effect known as tyramine pressor response with high blood pressure and risk of cerebral hemorrhage which can be fatal [42,167][42][108]. Finally, another important PK-DFI is the reduced bioavailability of ferrous from cow milk. Caseins in cow milk bind Fe2+ by clusters of phosphoserines, keeping it soluble in GI’s alkaline pH, preventing its free form from being available for absorption, thus decreasing its bioavailability in cases of ferrous supplement co-administration [168][109]. In addition, co-administration of mercaptopurine and cow milk in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemias reduces the bioavailability of the drug due to milk’s high content of xanthine oxidase, thus this co-administration should be avoided [169,170][110][111]. Meat products within Med-D, although consumed to a limited extent, are a valuable source of nutrients for a healthy and balanced diet. Their dietary value lies in their high protein content with essential amino acids, ferrous from red meat, vitamin B12 and other vitamins of B-complex, zinc, selenium, and phosphorus. Fat content is dependent on meat species, feeding system, as well as the meat part that is used in food [171][112]. As stated earlier, high-fat content may lead to raised salt and increase the solubilization of lipophilic drugs [38].2.2.5. Wine and Other Beverages

Wines, except for their alcohol content (~11% for whites and 15% for reds), have a rich composition of bioactive compounds such as polyphenols. Resveratrol, anthocyanins, catechins, and tannins (proanthocyanins and ellagitannins) are some of the most often found polyphenols with a higher content in red wines which also explicate the beneficial effect of from wine consumption [172,173][113][114]. One of the most known examples is the French paradox, the epidemiological observation of low coronary heart disease death rates despite high intake of dietary cholesterol and saturated fat in southern France which is attributed in red wine consumption in those populations [174][115]. Regarding DFIs, polyphenols can modulate the phase I and II metabolism as stated earlier but for wine this effect can be considered minimal compared to the effects of alcohol in the case of regular or heavy drinking. Alcohol can enhance the effects of medications, especially in cases of chronic conditions. PK-DFIs of alcohol are related mostly with induction of CYP2E1 and to a lesser extent CYP3A3 and CYP2A1. Heavy alcohol drinking can lead to PD-DFIs of alcohol such as sedation when combined with CNS acting drugs (sedatives, antihistamines, antidepressants, antipsychotics etc.), induce gastric bleeding when combined with aspirin and relative painkillers or anticoagulants, and hypoglycemia with antidiabetic drugs [43,175][43][116]. Regarding the vexed issue, the widespread opinion that concomitant drink of alcohol with antibiotics or other antimicrobials will cause toxicity or treatment failure, a recent review of the available evidence suggested that the data are poor and sometimes controversial [176][117]. The reduced efficacy refers mostly to erythromycin and doxycycline. Disulfiram-like reaction (distress, pain, flushes, irregular heartbeat) can occurs in co-administration of metronidazole, ketoconazole, griseofulvin and cephalosporines (i.e., cefuroxime, cefotetan, ceftriaxone, cefoperazone, ceftriazone). Ambiguous data for ADRs exist for trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole. On the other hand, penicillins, fluoroquinolones, azithromycin, tetracyclines, nitrofurantoin, secnidazole, tinidazole, and fluconazole have not been causally related to ADRs [176][117]. Another mechanism involved is the reduction in the immune response and epidemiological studies have shown alcohol abuse to be associated with an increased incidence of infectious diseases. But this is related mostly to cases of alcohol abuse, consumption of high content alcoholic drinks and overall, a poor quality of life regarding well-being and disease prevention. Thus, it is a good idea from the healthcare perspective, especially for heavy-drinking patients under treatment, to advise towards drinking cessation [177,178][118][119]. On the other hand, the moderate consumption of red wine seems to be beneficial in cases of immune protection due to its polyphenol content [177][118]. Thus, although the quality and quantity of data are vague, the avoidance of or reduction in consuming alcohol in low or moderate amounts (e.g., a social occasion with one glass of wine or beer) as is suggested through Med-D can be enjoyed.References

- Martínez-González, M.Á.; Hershey, M.S.; Zazpe, I.; Trichopoulou, A. Transferability of the Mediterranean Diet to Non-Mediterranean Countries. What Is and What Is Not the Mediterranean Diet. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1226.

- Willett, W.C.; Sacks, F.; Trichopoulou, A.; Drescher, G.; Ferro-Luzzi, A.; Helsing, E.; Trichopoulos, D. Mediterranean Diet Pyramid: A Cultural Model for Healthy Eating. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1995, 61, 1402S–1406S.

- Bach-Faig, A.; Berry, E.M.; Lairon, D.; Reguant, J.; Trichopoulou, A.; Dernini, S.; Medina, F.X.; Battino, M.; Belahsen, R.; Miranda, G.; et al. Mediterranean Diet Pyramid Today. Science and Cultural Updates. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 2274–2284.

- United Nations Educational, S. and C.O. The Mediterranean Diet. Intangible Heritage. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/archives/multimedia/document-1680-eng-2 (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Wright, C.M. Biographical Notes on Ancel Keys and Salim Yusuf: Origins and Significance of the Seven Countries Study and the INTERHEART Study. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2011, 5, 434–440.

- Trichopoulou, A.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Tong, T.Y.N.; Forouhi, N.G.; Khandelwal, S.; Prabhakaran, D.; Mozaffarian, D.; de Lorgeril, M. Definitions and Potential Health Benefits of the Mediterranean Diet: Views from Experts around the World. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 112.

- El Amrousy, D.; Elashry, H.; Salamah, A.; Maher, S.; Abd-Elsalam, S.M.; Hasan, S. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Improved Clinical Scores and Inflammatory Markers in Children with Active Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Randomized Trial. J. Inflamm. Res. 2022, 15, 2075–2086.

- Trichopoulou, A.; Costacou, T.; Bamia, C.; Trichopoulos, D. Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet and Survival in a Greek Population. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 2599–2608.

- Iaccarino Idelson, P.; Scalfi, L.; Valerio, G. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017, 27, 283–299.

- García-Fernández, E.; Rico-Cabanas, L.; Estruch, R.; Estruch, R.; Estruch, R.; Bach-Faig, A. Mediterranean Diet and Cardiodiabesity: A Review. Nutrients 2014, 6, 3474–3500.

- Dinu, M.; Pagliai, G.; Casini, A.; Sofi, F. Mediterranean Diet and Multiple Health Outcomes: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies and Randomised Trials. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 72, 30–43.

- Du, H.; Cao, T.; Lu, X.; Zhang, T.; Luo, B.; Li, Z. Mediterranean Diet Patterns in Relation to Lung Cancer Risk: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 844382.

- Bayán-Bravo, A.; Banegas, J.R.; Donat-Vargas, C.; Sandoval-Insausti, H.; Gorostidi, M.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F.; Guallar-Castillón, P. The Mediterranean Diet Protects Renal Function in Older Adults: A Prospective Cohort Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 432.

- Forsyth, C.; Kouvari, M.; D’Cunha, N.M.; Georgousopoulou, E.N.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Mellor, D.D.; Kellett, J.; Naumovski, N. The Effects of the Mediterranean Diet on Rheumatoid Arthritis Prevention and Treatment: A Systematic Review of Human Prospective Studies. Rheumatol. Int. 2018, 38, 737–747.

- Morales-Ivorra, I.; Romera-Baures, M.; Roman-Viñas, B.; Serra-Majem, L. Osteoarthritis and the Mediterranean Diet: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 30.

- Rees, K.; Takeda, A.; Martin, N.; Ellis, L.; Wijesekara, D.; Vepa, A.; Das, A.; Hartley, L.; Stranges, S. Mediterranean-Style Diet for the Primary and Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease; John Wiley and Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; Volume 2019.

- García-Casares, N.; Fuentes, P.G.; Barbancho, M.Á.; López-Gigosos, R.; García-Rodríguez, A.; Gutiérrez-Bedmar, M. Alzheimer’s Disease, Mild Cognitive Impairment and Mediterranean Diet. A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4642.

- Bakaloudi, D.R.; Chrysoula, L.; Leonida, I.; Kotzakioulafi, E.; Theodoridis, X.; Chourdakis, M. Impact of the Level of Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet on Blood Pressure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 5771–5780.

- Bakaloudi, D.R.; Chrysoula, L.; Kotzakioulafi, E.; Theodoridis, X.; Chourdakis, M. Impact of the Level of Adherence to Mediterranean Diet on the Parameters of Metabolic Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1514.

- Finicelli, M.; Di Salle, A.; Galderisi, U.; Peluso, G. The Mediterranean Diet: An Update of the Clinical Trials. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2956.

- Castro-Espin, C.; Agudo, A. The Role of Diet in Prognosis among Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Dietary Patterns and Diet Interventions. Nutrients 2022, 14, 348.

- Rufino-Palomares, E.E.; Pérez-Jiménez, A.; García-Salguero, L.; Mokhtari, K.; Reyes-Zurita, F.J.; Peragón-Sánchez, J.; Lupiáñez, J.A. Nutraceutical Role of Polyphenols and Triterpenes Present in the Extracts of Fruits and Leaves of Olea Europaea as Antioxidants, Anti-Infectives and Anticancer Agents on Healthy Growth. Molecules 2022, 27, 2341.

- Caponio, G.R.; Lippolis, T.; Tutino, V.; Gigante, I.; De Nunzio, V.; Milella, R.A.; Gasparro, M.; Notarnicola, M. Nutraceuticals: Focus on Anti-Inflammatory, Anti-Cancer, Antioxidant Properties in Gastrointestinal Tract. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1274.

- Abenavoli, L.; Procopio, A.C.; Paravati, M.R.; Costa, G.; Milić, N.; Alcaro, S.; Luzza, F. Mediterranean Diet: The Beneficial Effects of Lycopene in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3477.

- Scoditti, E.; Capurso, C.; Capurso, A.; Massaro, M. Vascular Effects of the Mediterranean Diet-Part II: Role of Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Olive Oil Polyphenols. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2014, 63, 127–134.

- Massaro, M.; Scoditti, E.; Carluccio, M.A.; De Caterina, R. Nutraceuticals and Prevention of Atherosclerosis: Focus on Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Mediterranean Diet Polyphenols. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2010, 28, e13–e19.

- Augimeri, G.; Bonofiglio, D. The Mediterranean Diet as a Source of Natural Compounds: Does It Represent a Protective Choice against Cancer? Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 920.

- Vivancos, M.; Moreno, J.J. Effect of Resveratrol, Tyrosol and Beta-Sitosterol on Oxidised Low-Density Lipoprotein-Stimulated Oxidative Stress, Arachidonic Acid Release and Prostaglandin E2 Synthesis by RAW 264.7 Macrophages. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 99, 1199–1207.

- Roman, G.C.; Jackson, R.E.; Gadhia, R.; Roman, A.N.; Reis, J. Mediterranean Diet: The Role of Long-Chain Omega-3 Fatty Acids in Fish; Polyphenols in Fruits, Vegetables, Cereals, Coffee, Tea, Cacao and Wine; Probiotics and Vitamins in Prevention of Stroke, Age-Related Cognitive Decline, and Alzheimer Disease. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 175, 724–741.

- Nadtochiy, S.M.; Redman, E.K. Mediterranean Diet and Cardioprotection: The Role of Nitrite, Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids, and Polyphenols. Nutrition 2011, 27, 733–744.

- Nomikos, T.; Fragopoulou, E.; Antonopoulou, S.; Panagiotakos, D.B. Mediterranean Diet and Platelet-Activating Factor: A Systematic Review. Clin. Biochem. 2018, 60, 1–10.

- Chatsisvili, A.; Sapounidis, I.; Pavlidou, G.; Zoumpouridou, E.; Karakousis, V.A.; Spanakis, M.; Teperikidis, L.; Niopas, I. Potential Drug-Drug Interactions in Prescriptions Dispensed in Community Pharmacies in Greece. Pharm. World Sci. 2010, 32, 187–193.

- Kohler, G.I.; Bode-Boger, S.M.; Busse, R.; Hoopmann, M.; Welte, T.; Boger, R.H. Drug-Drug Interactions in Medical Patients: Effects of in-Hospital Treatment and Relation to Multiple Drug Use. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000, 38, 504–513.

- Dechanont, S.; Maphanta, S.; Butthum, B.; Kongkaew, C. Hospital Admissions/Visits Associated with Drug-Drug Interactions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2014, 23, 489–497.

- Spanakis, M.; Spanakis, E.G.; Kondylakis, H.; Sfakianakis, S.; Genitsaridi, I.; Sakkalis, V.; Tsiknakis, M.; Marias, K. Addressing drug-drug and drug-food interactions through personalized empowerment services for healthcare. In Proceedings of the 38th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBS 2016), Orlando, FL, USA, 16–20 August 2016.

- Vizirianakis, I.S.; Spanakis, M.; Termentzi, A.; Niopas, I.; Kokkalou, E. Clinical and Pharmacogenomic Assessment of Herb-Drug Interactions to Improve Drug Delivery and Pharmacovigilance. In Plants in Traditional and Modern Medicine: Chemistry and Activity; Kokkalou, E., Ed.; Transworld Research Network: Kerala, India, 2010; ISBN 978-81-7895-432-5.

- Spanakis, M.; Sfakianakis, S.; Sakkalis, V.; Spanakis, E.G. PharmActa: Empowering Patients to Avoid Clinical Significant Drug(-)Herb Interactions. Medicines 2019, 6, 26.

- Lopes, M.; Coimbra, M.A.; Costa, M.D.C.; Ramos, F. Food supplement vitamins, minerals, amino-acids, fatty acids, phenolic and alkaloid-based substances: An overview of their interaction with drugs. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 1–35.

- Won, C.S.; Oberlies, N.H.; Paine, M.F. Mechanisms Underlying Food-Drug Interactions: Inhibition of Intestinal Metabolism and Transport. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 136, 186.

- Frankel, E.H.; McCabe, B.J.; Wolfe, J.J. Handbook of Food-Drug Interactions; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003; ISBN 1135504571.

- Kirby, B.J.; Unadkat, J.D. Grapefruit Juice, a Glass Full of Drug Interactions? Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 81, 631–633.

- Brown, C.; Taniguchi, G.; Yip, K. The Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitor-Tyramine Interaction. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1989, 29, 529–532.

- Chan, L.N.; Anderson, G.D. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Drug Interactions with Ethanol (Alcohol). Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2014, 53, 1115–1136.

- Amadi, C.N.; Mgbahurike, A.A. Selected Food/Herb-Drug Interactions: Mechanisms and Clinical Relevance. Am. J. Ther. 2018, 25, e423–e433.

- Briguglio, M.; Hrelia, S.; Malaguti, M.; Serpe, L.; Canaparo, R.; Dell’Osso, B.; Galentino, R.; De Michele, S.; Dina, C.Z.; Porta, M.; et al. Food Bioactive Compounds and Their Interference in Drug Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Profiles. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 277.

- Campos, M.G.; Machado, J.; Costa, M.L.; Lino, S.; Correia, F.; Maltez, F. Case Report: Severe Hematological, Muscle and Liver Toxicity Caused by Drugs and Artichoke Infusion Interaction in an Elderly Polymedicated Patient. Curr. Drug Saf. 2018, 13, 44–50.

- Rodríguez-Fragoso, L.; Martínez-Arismendi, J.L.; Orozco-Bustos, D.; Reyes-Esparza, J.; Torres, E.; Burchiel, S.W. Potential Risks Resulting from Fruit/Vegetable–Drug Interactions: Effects on Drug-Metabolizing Enzymes and Drug Transporters. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, R112–R124.

- Eagles, S.K.; Gross, A.S.; McLachlan, A.J. The Effects of Cruciferous Vegetable-Enriched Diets on Drug Metabolism: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Dietary Intervention Trials in Humans. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 108, 212–227.

- Lampe, J.W.; King, I.B.; Li, S.; Grate, M.T.; Barale, K.V.; Chen, C.; Feng, Z.; Potter, J.D. Brassica Vegetables Increase and Apiaceous Vegetables Decrease Cytochrome P450 1A2 Activity in Humans: Changes in Caffeine Metabolite Ratios in Response to Controlled Vegetable Diets. Carcinogenesis 2000, 21, 1157–1162.

- Foster, B.C.; Foster, M.S.; Vandenhoek, S.; Krantis, A.; Budzinski, J.W.; Arnason, J.T.; Gallicano, K.D.; Choudri, S. An in Vitro Evaluation of Human Cytochrome P450 3A4 and P-Glycoprotein Inhibition by Garlic. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2001, 4, 176–184.

- Piscitelli, S.C.; Burstein, A.H.; Welden, N.; Gallicano, K.D.; Falloon, J. The Effect of Garlic Supplements on the Pharmacokinetics of Saquinavir. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 34, 234–238.

- Sunaga, K.; Ohkawa, K.; Nakamura, K.; Ohkubo, A.; Harada, S.; Tsuda, T. Mechanism-Based Inhibition of Recombinant Human Cytochrome P450 3A4 by Tomato Juice Extract. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2012, 35, 329–334.

- Ohkubo, A.; Chida, T.; Kikuchi, H.; Tsuda, T.; Sunaga, K. Effects of Tomato Juice on the Pharmacokinetics of CYP3A4-Substrate Drugs. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 12, 464.

- Tsujimoto, M.; Agawa, C.; Ueda, S.; Yamane, T.; Kitayama, H.; Terao, A.; Fukuda, T.; Minegaki, T.; Nishiguchi, K. Inhibitory Effects of Juices Prepared from Individual Vegetables on CYP3A4 Activity in Recombinant CYP3A4 and LS180 Cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2017, 40, 1561–1565.

- Kumar, S.; Bouic, P.J.; Rosenkranz, B. In Vitro Assessment of the Interaction Potential of Ocimum Basilicum (L.) Extracts on CYP2B6, 3A4, and Rifampicin Metabolism. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 517.

- Kim, K.H.; Choi, W.S.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, H.; Yang, D.H.; Chae, S.C. Relationship between Dietary Vitamin K Intake and the Stability of Anticoagulation Effect in Patients Taking Long-Term Warfarin. Thromb. Haemost. 2010, 104, 755–759.

- Mahtani, K.R.; Heneghan, C.J.; Nunan, D.; Roberts, N.W. Vitamin K for improved anticoagulation control in patients receiving warfarin. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 5, CD009917.

- Samojlik, I.; Mijatović, V.; Petković, S.; Škrbić, B.; Božin, B. The Influence of Essential Oil of Aniseed (Pimpinella Anisum, L.) on Drug Effects on the Central Nervous System. Fitoterapia 2012, 83, 1466–1473.

- Gupta, R.C.; Chang, D.; Nammi, S.; Bensoussan, A.; Bilinski, K.; Roufogalis, B.D. Interactions between Antidiabetic Drugs and Herbs: An Overview of Mechanisms of Action and Clinical Implications. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2017, 9, 59.

- Hassanzadeh-Taheri, M.; Hassanpour-Fard, M.; Doostabadi, M.; Moodi, H.; Vazifeshenas-Darmiyan, K.; Hosseini, M. Co-Administration Effects of Aqueous Extract of Turnip Leaf and Metformin in Diabetic Rats. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2018, 8, 178.

- Zeng, M.; Zhang, L.; Li, M.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, N.; Ke, Y.; Feng, W.; Zheng, X. Estrogenic Effects of the Extracts from the Chinese Yam (Dioscorea Opposite Thunb.) and Its Effective Compounds in Vitro and in Vivo. Molecules 2018, 23, 11.

- Mohseni, M.S.M.; Golshani, B. Simultaneous Determination of Levodopa and Carbidopa from Fava Bean, Green Peas and Green Beans by High Performance Liquid Gas Chromatography. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2013, 7, 1004.

- Fernandes, J.; Fialho, M.; Santos, R.; Peixoto-Plácido, C.; Madeira, T.; Sousa-Santos, N.; Virgolino, A.; Santos, O.; Vaz Carneiro, A. Is olive oil good for you? A systematic review and meta-analysis on anti-inflammatory benefits from regular dietary intake. Nutrition 2020, 69, 110559.

- Papakonstantinou, V.D.; Lagopati, N.; Tsilibary, E.C.; Demopoulos, C.A.; Philippopoulos, A.I. A Review on Platelet Activating Factor Inhibitors: Could a New Class of Potent Metal-Based Anti-Inflammatory Drugs Induce Anticancer Properties? Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2017, 2017, 6947034.

- Schwingshackl, L.; Krause, M.; Schmucker, C.; Hoffmann, G.; Rücker, G.; Meerpohl, J.J. Impact of Different Types of Olive Oil on Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2019, 29, 1030–1039.

- Albadawi, D.A.I.; Ravishankar, D.; Vallance, T.M.; Patel, K.; Osborn, H.M.I.; Vaiyapuri, S. Impacts of Commonly Used Edible Plants on the Modulation of Platelet Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 605.

- Jeong, H.U.; Kwon, S.S.; Kong, T.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, H.S. Inhibitory Effects of Cedrol, β-Cedrene, and Thujopsene on Cytochrome P450 Enzyme Activities in Human Liver Microsomes. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2014, 77, 1522–1532.

- Bailey, D.G. Grapefruit-Medication Interactions. CMAJ 2013, 185, 507–508.

- Hanley, M.J.; Cancalon, P.; Widmer, W.W.; Greenblatt, D.J. The Effect of Grapefruit Juice on Drug Disposition. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2011, 7, 267–286.

- Seden, K.; Dickinson, L.; Khoo, S.; Back, D. Grapefruit-Drug Interactions. Drugs 2010, 70, 2373–2407.

- Guo, L.Q.; Yamazoe, Y. Inhibition of Cytochrome P450 by Furanocoumarins in Grapefruit Juice and Herbal Medicines. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2004, 25, 129–136.

- Lown, K.S.; Bailey, D.G.; Fontana, R.J.; Janardan, S.K.; Adair, C.H.; Fortlage, L.A.; Brown, M.B.; Guo, W.; Watkins, P.B. Grapefruit Juice Increases Felodipine Oral Availability in Humans by Decreasing Intestinal CYP3A Protein Expression. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 99, 2545–2553.

- Bailey, D.G.; Dresser, G.; Arnold, J.M. Grapefruit-Medication Interactions: Forbidden Fruit or Avoidable Consequences? CMAJ 2013, 185, 309–316.

- Zhou, S.; Lim, L.Y.; Chowbay, B. Herbal Modulation of P-Glycoprotein. Drug Metab. Rev. 2004, 36, 57–104.

- Bailey, D.G. Better to Avoid Grapefruit with Certain Statins. Am. J. Med. 2016, 129, e301.

- Bailey, D.G.; Dresser, G.K.; Bend, J.R. Bergamottin, Lime Juice, and Red Wine as Inhibitors of Cytochrome P450 3A4 Activity: Comparison with Grapefruit Juice. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003, 73, 529–537.

- Chen, M.; Zhou, S.Y.; Fabriaga, E.; Zhang, P.H.; Zhou, Q. Food-Drug Interactions Precipitated by Fruit Juices Other than Grapefruit Juice: An Update Review. J. Food Drug Anal. 2018, 26, S61–S71.

- Petric, Z.; Žuntar, I.; Putnik, P.; Kovačević, D.B. Food–Drug Interactions with Fruit Juices. Foods 2021, 10, 33.

- An, G.; Mukker, J.K.; Derendorf, H.; Frye, R.F. Enzyme- and transporter-mediated beverage-drug interactions: An update on fruit juices and green tea. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 55, 1313–1331.

- Dresser, G.K.; Bailey, D.G.; Leake, B.F.; Schwarz, U.I.; Dawson, P.A.; Freeman, D.J.; Kim, R.B. Fruit Juices Inhibit Organic Anion Transporting Polypeptide-Mediated Drug Uptake to Decrease the Oral Availability of Fexofenadine. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2002, 71, 11–20.

- Kamath, A.V.; Yao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Chong, S. Effect of Fruit Juices on the Oral Bioavailability of Fexofenadine in Rats. J. Pharm. Sci. 2005, 94, 233–239.

- Grenier, J.; Fradette, C.; Morelli, G.; Merritt, G.J.; Vranderick, M.; Ducharme, M.P. Pomelo Juice, but Not Cranberry Juice, Affects the Pharmacokinetics of Cyclosporine in Humans. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006, 79, 255–262.

- Gertz, B.J.; Holland, S.D.; Kline, W.F.; Matuszewski, B.K.; Freeman, A.; Quan, H.; Lasseter, K.C.; Mucklow, J.C.; Porras, A.G. Studies of the Oral Bioavailability of Alendronate. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1995, 58, 288–298.

- Tapaninen, T.; Neuvonen, P.J.; Niemi, M. Orange and Apple Juice Greatly Reduce the Plasma Concentrations of the OATP2B1 Substrate Aliskiren. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 71, 718–726.

- Malhotra, S.; Bailey, D.G.; Paine, M.F.; Watkins, P.B. Seville Orange Juice-Felodipine Interaction: Comparison with Dilute Grapefruit Juice and Involvement of Furocoumarins. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001, 69, 14–23.

- Karmakar, S.; Biswas, S.; Bera, R.; Mondal, S.; Kundu, A.; Ali, M.A.; Sen, T. Beverage-Induced Enhanced Bioavailability of Carbamazepine and Its Consequent Effect on Antiepileptic Activity and Toxicity. J. Food Drug Anal. 2015, 23, 327–334.

- Backman, J.T.; Mäenpää, J.; Belle, D.J.; Wrighton, S.A.; Kivistö, K.T.; Neuvonen, P.J. Lack of Correlation between in Vitro and m Vivo Studies on the Effects of Tangeretin and Tangerine Juice on Midazolam Hydroxylation. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000, 67, 382–390.

- Morita, T.; Akiyoshi, T.; Sato, R.; Uekusa, Y.; Katayama, K.; Yajima, K.; Imaoka, A.; Sugimoto, Y.; Kiuchi, F.; Ohtani, H. Citrus Fruit-Derived Flavanone Glycoside Narirutin Is a Novel Potent Inhibitor of Organic Anion-Transporting Polypeptides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 14182–14191.

- Akamine, Y.; Miura, M.; Komori, H.; Saito, S.; Kusuhara, H.; Tamai, I.; Ieiri, I.; Uno, T.; Yasui-Furukori, N. Effects of One-Time Apple Juice Ingestion on the Pharmacokinetics of Fexofenadine Enantiomers. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2014, 70, 1087–1095.

- Jeon, H.; Jang, I.J.; Lee, S.; Ohashi, K.; Kotegawa, T.; Ieiri, I.; Cho, J.Y.; Yoon, S.H.; Shin, S.G.; Yu, K.S.; et al. Apple Juice Greatly Reduces Systemic Exposure to Atenolol. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 75, 172–179.

- Morita, T.; Akiyoshi, T.; Tsuchitani, T.; Kataoka, H.; Araki, N.; Yajima, K.; Katayama, K.; Imaoka, A.; Ohtani, H. Inhibitory Effects of Cranberry Juice and Its Components on Intestinal OATP1A2 and OATP2B1: Identification of Avicularin as a Novel Inhibitor. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 3310–3320.

- Srinivas, N.R. Cranberry Juice Ingestion and Clinical Drug-Drug Interaction Potentials; Review of Case Studies and Perspectives. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 16, 289–303.

- Greenblatt, D.J.; Von Moltke, L.L.; Perloff, E.S.; Luo, Y.; Harmatz, J.S.; Zinny, M.A. Interaction of Flurbiprofen with Cranberry Juice, Grape Juice, Tea, and Fluconazole: In Vitro and Clinical Studies. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006, 79, 125–133.

- Lilja, J.J.; Backman, J.T.; Neuvonen, P.J. Effects of Daily Ingestion of Cranberry Juice on the Pharmacokinetics of Warfarin, Tizanidine, and Midazolam—Probes of CYP2C9, CYP1A2, and CYP3A4. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 81, 833–839.

- Srinivas, N.R. Is Pomegranate Juice a Potential Perpetrator of Clinical Drug-Drug Interactions? Review of the in Vitro, Preclinical and Clinical Evidence. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2013, 38, 223–229.

- Mohamed Pakkir Maideen, N.; Balasubramanian, R.; Muthusamy, S.; Nallasamy, V. An Overview of Clinically Imperative and Pharmacodynamically Significant Drug Interactions of Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS) Blockers. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2022, 18, e110522204611.

- Batra, V.; Villgran, V. Hyperkalemia from Dietary Supplements. Cureus 2016, 8, e859.

- Yusuff, K.B.; Emeka, P.M.; Attimarad, M. Concurrent Administration of Date Palm Fruits with Lisinopril Increases Serum Potassium Level in Male Rabbits. Int. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 14, 93–98.

- St-Jules, D.E.; Goldfarb, D.S.; Sevick, M.A. Nutrient Non-Equivalence: Does Restricting High-Potassium Plant Foods Help to Prevent Hyperkalemia in Hemodialysis Patients? J. Ren. Nutr. 2016, 26, 282–287.

- Huang, X.; Jiménez-Molén, J.J.; Lindholm, B.; Cederholm, T.; Ärnlöv, J.; Risérus, U.; Sjögren, P.; Carrero, J.J. Mediterranean Diet, Kidney Function, and Mortality in Men with CKD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 8, 1548–1555.

- Molina-Vega, M.; Gómez-Pérez, A.M.; Tinahones, F.J. Fish in the Mediterranean diet. In The Mediterranean Diet: An Evidence-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Preedy, V.R., Watson, R.R., Eds.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 275–284.

- Méndez, L.; Dasilva, G.; Taltavull, N.; Romeu, M.; Medina, I. Marine Lipids on Cardiovascular Diseases and Other Chronic Diseases Induced by Diet: An Insight Provided by Proteomics and Lipidomics. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 258.

- Vanschoonbeek, K.; Feijge, M.A.; Paquay, M.; Rosing, J.; Saris, W.; Kluft, C.; Giesen, P.L.; de Maat, M.P.; Heemskerk, J.W. Variable Hypocoagulant Effect of Fish Oil Intake in Humans: Modulation of Fibrinogen Level and Thrombin Generation. Arter. Thromb Vasc Biol 2004, 24, 1734–1740.

- Buckley, M.S.; Goff, A.D.; Knapp, W.E. Fish Oil Interaction with Warfarin. Ann. Pharmacother. 2004, 38, 50–53.

- Jalili, M.; Dehpour, A.R. Extremely Prolonged INR Associated with Warfarin in Combination with Both Trazodone and Omega-3 Fatty Acids. Arch. Med. Res. 2007, 38, 901–904.

- Pryce, R.; Bernaitis, N.; Davey, A.K.; Badrick, T.; Anoopkumar-Dukie, S. The Use of Fish Oil with Warfarin Does Not Significantly Affect Either the International Normalised Ratio or Incidence of Adverse Events in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation and Deep Vein Thrombosis: A Retrospective Study. Nutrients 2016, 8, 578.

- Jung, H.; Perergina, A.A.; Rodriguez, J.M.; Moreno- Esparza, R. The Influence of Coffee with Milk and Tea with Milk on the Bioavailability of Tetracycline. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 1997, 18, 459–463.

- KANEKO, J.; TANIMUKAI, H. MONOAMINE OXIDASE INHIBITORS (MAO). Sogo. Rinsho. 1964, 13, 833–846.

- Kibangou, I.B.; Bouhallab, S.; Henry, G.; Bureau, F.; Allouche, S.; Blais, A.; Guérin, P.; Arhan, P.; Bouglé, D.L. Milk Proteins and Iron Absorption: Contrasting Effects of Different Caseinophosphopeptides. Pediatr. Res. 2005, 58, 731–734.

- De Lemos, M.L.; Hamata, L.; Jennings, S.; Leduc, T. Interaction between Mercaptopurine and Milk. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2007, 13, 237–240.

- Sofianou-Katsoulis, A.; Khakoo, G.; Kaczmarski, R. Reduction in Bioavailability of 6-Mercaptopurine on Simultaneous Administration with Cow’s Milk. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2006, 23, 485–487.

- Pereira, P.M.C.C.; Vicente, A.F.R.B. Meat Nutritional Composition and Nutritive Role in the Human Diet. Meat Sci. 2013, 93, 586–592.

- Fernandes, I.; Pérez-Gregorio, R.; Soares, S.; Mateus, N.; De Freitas, V.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Feliciano, A.S. Wine Flavonoids in Health and Disease Prevention. Molecules 2017, 22, 292.

- Snopek, L.; Mlcek, J.; Sochorova, L.; Baron, M.; Hlavacova, I.; Jurikova, T.; Kizek, R.; Sedlackova, E.; Sochor, J. Contribution of Red Wine Consumption to Human Health Protection. Molecules 2018, 23, 1684.

- Renaud, S.; de Lorgeril, M. Wine, Alcohol, Platelets, and the French Paradox for Coronary Heart Disease. Lancet 1992, 339, 1523–1526.

- Weathermon, R.; Crabb, D.W. Alcohol and Medication Interactions. Alcohol Res. Health 1999, 23, 40.

- Mergenhagen, K.A.; Wattengel, B.A.; Skelly, M.K.; Clark, C.M.; Russo, T.A. Fact versus Fiction: A Review of the Evidence behind Alcohol and Antibiotic Interactions. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e02167-19.

- Romeo, J.; Würnberg, J.; Nova, E.; Díaz, L.E.; Gómez-Martinez, S.; Marcos, A. Moderate Alcohol Consumption and the Immune System: A Review. Br. J. Nutr. 2007, 98, S111–S115.

- Foster, J.H.; Powell, J.E.; Marshall, E.J.; Peters, T.J. Quality of Life in Alcohol-Dependent Subjects--a Review. Qual. Life Res. 1999, 8, 255–261.