Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Gongbing Shan and Version 2 by Conner Chen.

The immense charm of soccer to millions of players and spectators can be traced back to the most prime idea of the game: to score goals—an idea that will always be captivating. This basic idea shapes the soccer scoring technique (SST) to be the crucial and final determinant of every offensive-maneuver fate of any team. Therefore, the identification of SSTs is particularly important.

- biomechanical modeling

- proprioceptive shooting volume

- zero-possession shot

1. Introduction

The immense charm of soccer to millions of players and spectators can be traced back to the most prime idea of the game: to score goals—an idea that will always be captivating. This basic idea shapes the soccer scoring technique (SST) to be the crucial and final determinant of every offensive-maneuver fate of any team [1]. It is well known that goals are relatively rare in soccer. Various ways in which a team goes towards scoring a goal can be considered an extemporaneous show, where emotion increases over time and is suddenly released after a goal is scored [2][3][2,3]. As such, various SSTs for scoring goals are ultimately the source of excitement that make soccer the number one sport in the world [2][4][2,4]. Since diverse SSTs are the last destination that determines the outcome of every “emotional drama,” the quality of performing these SSTs is obviously an essential core of soccer coaching and training; of course, it should be a focus of biomechanical investigations on soccer. Unfortunately, biomechanical studies on various SSTs fall far behind the practice, resulting in a practical scenario that most participants acquire SSTs through personal experience without research-based instruction [3][5][6][3,5,6].

Nowadays, in professional games, airborne shots happen more often and the time for making a shot is becoming tighter. FIFA (Fédération Internationale de Football Association) has impressively portrayed the trend as “every nanosecond is special” [7]. These emerging airborne SSTs, such as bicycle kick, jumping side volley, dividing scorpion kick, and more, appear to be exceptionally complex and are widely regarded as the natural ability of soccer superstars [8]. However, one thing is clear: that these superb SSTs are trained motor skills. Research shows that biomechanical quantification on virtuosic humans can make these skills clearer and easier to be learned, i.e., knowledge gained from biomechanical studies can help us learn complex motor skills while reducing the risk of training-related injuries [9][10][11][12][9,10,11,12]. Clearly, relying on athletes’ talent to improve these superb SSTs can hardly be considered a viable learning strategy. Biomechanical studies will play an import role in helping practitioners launch science-based (not experience-based) motor learning to optimize their practice.

23. Identification of SSTs

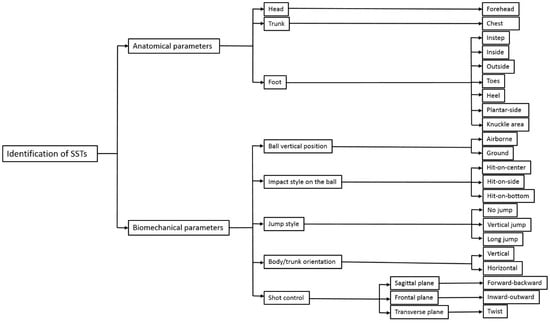

In soccer, shots lead to goals and goals win games. Hence, it is logical for both researchers and practitioners to explore all means that could increase the chance and effectiveness of shots taken. Until now, practitioners have unearthed numerous SSTs that can be applied in various game situations; in contrast, scientific investigations (especially biomechanical studies) have only been conducted in a few of the SSTs seen in the game [3][5][3,5]. This scenario has resulted in the lack of science-based SST training in current soccer practice. Until 2021, neither researchers nor practitioners knew how many SSTs were available for the game [3]. As such, the names/terms of SSTs used in public broadcasting, documentations, and reports were confusing, e.g., the jumping side volley was often misreported in the professional leagues as a bicycle kick [13][14][15][16][15,16,17,18]. As matter of a fact, the former is a side-kick technique and the latter is an overhead-kick skill. In order to reduce the ambiguity and increase clarity in both research and training practice, every SST has to be clearly defined. In 2021, Zhang et al. established the first terminological system for clearly identifying various SSTs [3]. The research team collected 579 elite soccer goals from international professional tournaments for their study. The essential rule of their collection was that every goal was clearly repeatable, i.e., trainable. From the point view of biomechanics, different SSTs should be linked to certain anatomical parts and show distinct motor-control parameters. Therefore, their identification of SSTs was performed by applying both anatomical and biomechanical parameters. The anatomical parameters included segments and the anatomical landmarks on the segments used during shots. The biomechanical parameters covered the variables describing the dynamic instants of various shooting situations. These variables are associated with ball spatial position, impact style on the ball, jump style, body/trunk orientation at the instant of shooting, and shot control. Figure 1 summarizes the variables applied in the terminological system. Some examples of unique SSTs are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Anatomical and biomechanical parameters used in the identification of SSTs.

Table 1. Examples of unique SSTs. Except for the bicycle kick [8][22][8,24], jumping side volley [8][23][8,25], and knuckleball kick [24][25][26,27], there are still no reports on the biomechanical studies of the rest of the unique SSTs.

| SST | Anatomical Parameters |

Biomechanical Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Bicycle kick | Foot, instep | Airborne ball, hit-on-center, vertical jump, trunk lean backward horizontally, forward kick |

| Jumping side volley | Foot, instep | Airborne ball, hit-on-center, vertical jump, trunk lean sideward horizontally, forward kick |

| Jumping front volley | Foot, instep | Airborne ball, hit-on-center, vertical jump, vertical trunk, forward kick |

| Long-jump turning header | Forehead | Airborne ball, hit-on-center, long jump, vertical trunk, head twisting |

| Diving header | Forehead | Airborne ball, hit-on-center, long jump, trunk lean forward horizontally |

| Diving scorpion kick | Foot, heel | Airborne ball, hit-on-center, long jump, trunk lean forward horizontally, backward kick |

| Trivela kick | Foot, outside | Ground ball, hit-on-side, no jump, vertical trunk, forward kick |

| Jumping turning kick | Foot, outside | Airborne ball, hit-on-center, vertical jump, vertical and twisting trunk |

| Jumping breaking kick | Foot, plantar side | Airborne ball, hit-on-center, long jump, vertical trunk |

| Sliding kick | Foot, plantar side | Ground ball, hit-on-center, no jump, trunk lean backward horizontally |

| Knuckleball kick | Foot, knuckle area | Ground ball, hit-on-center, no jump, vertical trunk, forward kick |