Multisensory integration refers to sensory inputs from different sensory modalities being processed simultaneously to produce a unitary output. Surrounded by stimuli from multiple modalities, animals utilize multisensory integration to form a coherent and robust representation of the complex environment. Many interesting paradigms of multisensory integration have been characterized in

C. elegans, for which input convergence occurs at the sensory neuron or the interneuron level.

, for which input convergence occurs at the sensory neuron or the interneuron level.

- multisensory integration

- Caenorhabditis elegans

- sensory processing

1. General Introduction

2. Multisensory Integration in C. elegans

2.1. Sensory Processing in C. elegans

C. elegans has 60 sensory neurons that can sense a variety of sensory modalities, including smell, taste, touch, temperature, light, color, oxygen, CO2, humidity, proprioception, magnetic field and sound [36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. For each environmental stimulus assayed in isolation, the fundamental neural circuit is well characterized [28] and the corresponding behavioral output is generally robust. Worms use diverse protein receptors to sense environmental stimuli. The C. elegans genome encodes over 1000 predicted G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), many of which are likely to function as receptors in sensory neurons [37]. The one confirmed odorant receptor is ODR-10, which detects diacetyl [46]. GPCR LITE-1 has been shown to be a photoreceptor [47]. It has been demonstrated that the receptor guanylyl cyclase GCY-35 is an oxygen sensor [48]. Several receptor guanylyl cyclases and a glutamate receptor have been proposed as thermo-receptors [49][50][49,50]. The mechano-sensor is thought to be made up of two ion channel subunits, MEC-4 and MEC-10, from the degenerin/epithelial Na+ channel (DEG/ENaC) family [51][52][51,52]. When the GPCR protein receptors are activated by a stimulus, the signal is transduced by two types of downstream ion channels [37][38][37,38]. One type consists of the TRP (transient receptor potential) channels, OSM-9 and OCR-2 [53][54][53,54]. The other type of downstream signaling transduction is mediated by the second messenger cGMP, involving receptor guanylyl cyclases and cyclic nucleotide-gated channels TAX-4 and TAX-2 [55][56][55,56]. Both types of channels can mobilize calcium, open voltage-gated calcium channels and activate the sensory neuron. The organization of the sensory system from all modalities is vastly different in C. elegans compared to mammals due to its numerical simplicity. Take the olfactory sensory neurons, for example. In C. elegans, a pair of each AWA, AWB and AWC neurons serve as the primary odorant chemosensory neurons, while worms are likely to express around 100 GPCRs as presumed odorant receptors [57]. Therefore, each odorant-sensing neuron expresses many receptors. This is in contrast to the “one neuron, one receptor” rule in mammals, which refers to the fact that each olfactory sensory neuron expresses one and only one olfactory receptor [58]. In the ascending pathways beyond the sensory neuron layer, the sensory systems in mammals are much more complex. Their projections travel a long distance and project to multiple higher brain regions. In C. elegans, interneurons comprise the largest group of neurons, which is probably the counterpart of the higher brain regions in mammals [24]. They can be divided into first-layer, second-layer and commander interneurons. Sensory neurons project to different layers of interneurons and converge into five commander interneurons that control muscle movement [59].2.2. C. elegans Performs Multisensory Integration

All animals, including lower organisms such as C. elegans, can integrate information from multiple channels to form an accurate presentation of the complex environment. The integration process allows animals to make better choices based on the information they have received. The environment of C. elegans may contain both beneficial elements such as mates and food, but also harmful elements such as poison and predators. How to integrate environmental cues in a context-dependent manner and make an appropriate decision is a central theme in the studies of C. elegans neurobiology. Despite having just 60 sensory neurons, C. elegans exhibits an array of highly sensitive sensory modalities and displays diverse paradigms of multisensory integration [21][22][21,22]. These paradigms can probably be divided into two categories: (1) exposing C. elegans to two sensory modalities of opposing valence and studying how worms make decisions; (2) exposing C. elegans to stimuli from two sensory modalities and examining how the behavior evoked by one stimulus is altered by a second stimulus. All the paradigms found in C. elegans seem to be consistent in that multisensory integration can change perception. Processing various sensory inputs at the level of sensory neurons or sensilla in the periphery is one way to accomplish multisensory integration. It can also be accomplished by integrating at the interneuron or central nervous system levels. In addition, an animal’s internal state and past experiences can top-down alter the output of sensory-evoked behavior. Below is a detailed discussion of C. elegans’ integration paradigms and top-down mechanisms. Theoretically, two stimuli from the same sensory modality, for example, two different odorants, can also interact with each other. This scenario does not seem to be included in studies of multisensory integration in mammals but is often studied in C. elegans, providing many interesting sensory integration paradigms. In evolution, sensory integration from the same modality is likely to be fundamental to sensory integration from multiple modalities [12]. It has been found that low concentrations of different odorants often have a synergistic effect in mice [60]. This is reminiscent of the principle of inverse effectiveness. Therefore, some paradigms demonstrating sensory integration from the same modality in C. elegans will also be discussed below.2.3. Integration at the Level of Sensory Neurons

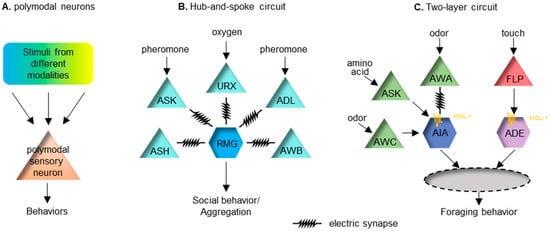

Many organisms contain polymodal sensory neurons, meaning that those neurons can each sense multiple stimuli from different sensory modalities. In that case, polymodal sensory neurons can easily integrate sensory information from different modalities. Although sensory neurons are highly specialized in mammals, polymodal sensory neurons do exist, as exemplified by cutaneous C-fiber nociceptors [61][62][61,62]. They can respond to more than one type of noxious stimuli applied to the skin, usually mechanical, chemical and thermal [61][62][61,62]. Studying these polymodal nociceptors has provided great significance in pain management [63]. Many sensory neurons in C. elegans are polymodal. For example, the ASH neuron pair is the main nociceptor sensory neuron, which mediates avoidance responses to noxious stimuli [37]. It can sense an array of aversive cues, such as high osmolality, quinine, nose touch, repellent chemicals, heavy metals, and so on. Interestingly, after ASH activation, C. elegans can separately process stimuli from different modalities by innovating different downstream postsynaptic receptors [64]. Although high osmolality and nose touch both activate ASH neurons, high osmolality utilizes both non-NMDA and NMDA receptor subunits to mediate the avoidance response, whereas nose touch only triggers non-NMDA receptors post-synaptically [64][65][64,65]. Genetic and electrophysiological analysis suggests that this modality-specific signal transduction is because high osmolality enables increased glutamate released from ASH neurons, which is sufficient to activate both non-NMDA and NMDA receptors [65]. In addition to ASH, many other sensory neurons in C. elegans are also polymodal. For example, the chemosensory AWC neuron pair can respond to temperature [66][67][66,67]. Similarly, the AFD neuron pair primarily senses temperature but can also respond to CO2 [68][69][68,69]. These polymodal neurons all have the ability to mediate multisensory integration (Figure 1A).

2.4. Integration at the Level of Interneurons

Multisensory encoding in mammals takes place in many higher brain regions, such as the superior colliculus (SC) in the midbrain and many regions in the cerebral cortex [6][70][6,70]. Due to the significant restriction on the number of neurons, C. elegans often encodes the valance of a stimulus at the sensory neuron level [71]. Nonetheless, many paradigms of multisensory integration occur at the first- and second-layer interneurons to modulate the sensory output. The hub-and-spoke circuit is a well-known sensory integration paradigm. One of these regulates the worm’s social behavior, or aggregation. In this circuit, the interneuron RMG acts as the hub, linking to multiple sensory neurons (the spokes) with gap junctions [72]. High activity in the RMG is essential for promoting social aggregation, of which the activity level can be modulated by several spoke neurons that sense diverse stimuli, including oxygen, sex pheromones and noxious chemicals (Figure 1B). This circuit connection motif integrates cross-modal sensory inputs to ensure a coherent output. Another similar hub-and-spoke circuit regulates nose touch response [73][74][75][73,74,75]. This involves the interneuron RIH being the hub connecting to sensory neurons ASH, FLP and OLQ responding to gentle touch via gap junctions. Other interneurons can also serve as the node in a circuit. Interneuron AIA can receive inputs from many chemosensory neurons. AIA receives excitatory input from an electrical synapse and disinhibitory inputs via chemical synapses [76]. The two types of inputs need to happen coincidently to improve the reliability of AIA’s response [76]. The logic of this integrating neuron seems to relate closely to the temporal principle of multisensory integration. Recently, a two-layer integration has been reported to modulate foraging behavior in C. elegans [77]. Forage is a stereotyped local search behavior looking for food. The behavior requires redundant inhibitory inputs from two interneuron pairs, AIA and ADE, which receive chemosensory and mechanosensory food-related cues, respectively [77]. Sensory cues symbolizing food are first organized into the chemosensory cues that are integrated at AIA and the mechanosensory cues that are integrated at ADE. Input from these two neurons subsequently integrates into the next layer of interneurons. Local search behavior can be triggered when either of these two sensory cues is removed (Figure 1C).2.5. Top-Down Mechanisms in the Multisensory Integration

Sensory information transduction is thought to follow through a hierarchy of brain areas that are progressively more complex. “Top-down” refers to the influences of complex information from higher brain regions that shapes early sensory processing steps. Top-down influences can affect sensory processing at all cortical and thalamic levels [78]. Common top-down modulators of sensory processing can include stress, attention, expectation, emotion, motivation and learned experience [78][79][80][81].Sensory information transduction is thought to follow through a hierarchy of brain areas that are progressively more complex. “Top-down” refers to the influences of complex information from higher brain regions that shapes early sensory processing steps. Top-down influences can affect sensory processing at all cortical and thalamic levels [89]. Common top-down modulators of sensory processing can include stress, attention, expectation, emotion, motivation and learned experience [89–92].

Although C. elegans lacks cognition and emotion, the sensory output can be influenced by its past experience and internal physiological states, such as hunger and sickness. The most well-studied top-down modulator in C. elegans is probably starvation, likely to be due to a lack of other top-down cognitive or emotional modulators. Hunger will increase C. elegans’ preference for seeking attractive odors cueing for food availability in the risk of other harmful stimuli [82][83][84].Although C. elegans lacks cognition and emotion, the sensory output can be influenced by its past experience and internal physiological states, such as hunger and sickness. The most well-studied top-down modulator in C. elegans is probably starvation, likely to be due to a lack of other top-down cognitive or emotional modulators. Hunger will increase C. elegans’ preference for seeking attractive odors cueing for food availability in the risk of other harmful stimuli [81,93,94].

In a risk-reward choice assay [82], C. elegans is trapped inside a circle of a repulsive hyperosmotic fructose solution, while an attractive food odor is placed outside the circle. The outcome is scored on whether worms cross the aversive circle to reach the attractive odor. Almost no worms would exit the circle in the initial 15 min. However, after being starved for 5 h, almost 80% of the worms would exit the repulsive circle, seeking the attractive odor. The interneuron RIM is identified as modulating this decision via a top-down extra-synaptic aminergic signal [82]. In another scenario of multisensory integration between opposing valences, the insulin/IGF-1 signaling (IIS) pathway is mediating the signal of hunger to decrease responses to the repellent gustatory cue [84]. Several other neuromodulators have also been found to relay the signal of starvation to functionally reconfigure sensory processing and, presumably, they can also mediate top-down regulation impinging upon multisensory integration.In a risk-reward choice assay [81], C. elegans is trapped inside a circle of a repulsive hyperosmotic fructose solution, while an attractive food odor is placed outside the circle. The outcome is scored on whether worms cross the aversive circle to reach the attractive odor. Almost no worms would exit the circle in the initial 15 min. However, after being starved for 5 h, almost 80% of the worms would exit the repulsive circle, seeking the attractive odor. The interneuron RIM is identified as modulating this decision via a top-down extra-synaptic aminergic signal [81]. In another scenario of multisensory integration between opposing valences, the insulin/IGF-1 signaling (IIS) pathway is mediating the signal of hunger to decrease responses to the repellent gustatory cue [94]. Several other neuromodulators have also been found to relay the signal of starvation to functionally reconfigure sensory processing and, presumably, they can also mediate top-down regulation impinging upon multisensory integration.

Past experience is another well-studied top-down modulator for sensory processing in C. elegans. A recent study demonstrated how worms can learn to navigate a T-maze to locate food via multisensory cues [85][95]. In general, past experience affects sensory processing via reshaping the synapse. Here, rwesearchers provide two examples to demonstrate how prior experience can change either the strength or the composition of the synapse to enable plasticity. C. elegans does not have an innately preferred temperature. Instead, it remembers its cultivation temperature and moves to that temperature when subjected to a temperature gradient [86][96]. This sensory memory is encoded by the synaptic strength between the thermo-sensory neuron pair AFD and its downstream interneuron AIY [87][97]. Under warmer temperatures, this synapse is strengthened, enabling worms to move to warmth and vice versa. Similarly, C. elegans cultivated at a certain NaCl concentration can remember this concentration and travel to it when subjected to a NaCl gradient [88][98]. This gustatory memory is encoded by differentially innervating the glutamate receptors in the AIB neuron, which is postsynaptic to the salt-sensing neuron ASE right (ASER). At a higher salt cultivation condition, decreasing NaCl concentration causes ASER activation, triggers glutamate released from ASER and subsequently activates the excitatory glutamate receptor GLR-1 in the downstream AIB neurons, whereas, cultivated in a lower salt environment, glutamate released from ASER activates the inhibitory glutamate receptor AVR-14 in AIB instead [89][99].