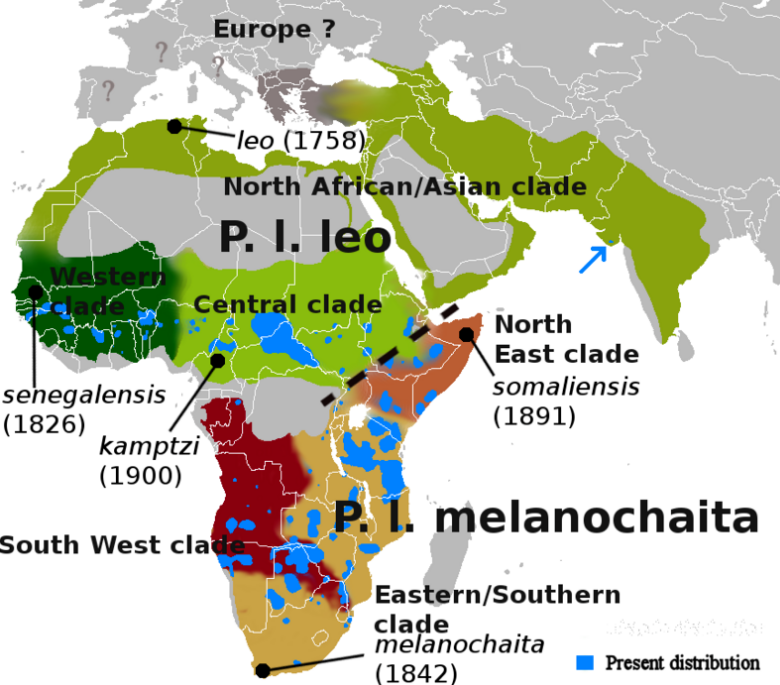

The Central African lion is a Panthera leo leo population in northern parts of Central and East Africa. This population has been fragmented into small and isolated groups since the 1950s. It is threatened by loss of habitat and prey base and trophy hunting. In 2005, a Lion Conservation Strategy was developed for West and Central Africa. Results of phylogeographic research indicate that the Central African lion clade forms a phylogenetic group with lion samples from West and North Africa, the Middle East and India . This group diverged from lions in southern parts of East and Southern Africa at least 50,000 years ago. Morphometric analysis of lion skulls corroborates the assessment of two major evolutionary lion clusters, one in Sub-Saharan Africa and the other in North Africa and Asia.

- lion

- lions

- population

1. Characteristics

The lion's fur varies in colour from light buff to dark brown. It has rounded ears and a black tail tuft. Average head-to-body length of male lions is 2.47–2.84 m (8.1–9.3 ft) with a weight of 148.2–190.9 kg (327–421 lb). Females are smaller and less heavy.[1]

2. Taxonomy

A lion from Constantine, Algeria was the type specimen for the specific name Felis leo used by Linnaeus in 1758.[2] In the 20th century, several lion zoological specimens from Central Africa were described and proposed as subspecies:[3]

- Felis leo kamptzi described in 1900 by Paul Matschie was a lion skin from Cameroon.[4]

- Leo leo azandicus described in 1924 by Joel Asaph Allen was a lion that was killed in 1912 in northeastern Belgian Congo as part of a zoological collection comprising 588 carnivore specimens.[5]

In the following decades, there has been much debate regarding classification of lion subspecies:

- In 1939, Glover Morrill Allen recognized Felis leo kamptzi, F. l. bleyenberghi and F. l. azandicus as valid taxa among ten lion subspecies.[6][7]

- The British taxonomist Reginald Innes Pocock subordinated lions to the genus Panthera in 1930 when he wrote about Asiatic lion specimens in the zoological collection of the British Museum of Natural History.[8]

- Three decades later, John Ellerman and Terence Morrison-Scott recognized only two lion subspecies in the Palearctic realm, namely P. l. leo in Africa and P. l. persica in Asia.[9]

- In 2005, Wallace Christopher Wozencraft recognized P. l. kamptzi and P. l. azandica as valid taxa.[3]

- In 2016, IUCN Red List assessors used P. l. leo for all lion populations in Africa.[10]

In 2017, lion populations in North, West and Central Africa and Asia were subsumed to the nominate subspecies P. l. leo by the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group.[11]

2.1. Phylogeographic Research

Since the beginning of the 21st century, several phylogenetic studies were conducted to aid clarifying the taxonomic status of lion samples kept in natural history museums and collected in the wild. Scientists analysed between 32 and 480 lion samples from up to 22 countries. They all agree that the species lion comprises two evolutionary groups, one in the northern and eastern parts of its historical range, the other in East and Southern Africa; these groups diverged at least 50,000 years ago. They assume that tropical rainforest and the East African Rift constituted major barriers between the two groups.[12][13][14][15][16][17]

Captive lions in Ethiopia's Addis Ababa Zoo were found to be genetically similar to wild lions from Cameroon and Chad.[18]

Among six samples from captive lions that originated in Ethiopia, one clustered with samples from the Sahel, but five clustered with samples from East Africa.[15] For a subsequent study, also eight wild lion samples from the Ethiopian Highlands were included in the analysis. Of these,[17]

- three clustered with the Central African lion clade, namely samples from Gambela and Bale Mountains National Parks and the Ogaden region, and

- five clustered with samples from East Africa.

Scientists therefore assume that the Ethiopian Highlands east and west of the Rift Valley is a genetic admixture zone between both phylogeographic groups. Samples from Garamba National Park also clustered with the Central African lion.[17]

3. Distribution and Habitat

The historical range of the Central African lion reached from the lower Niger river in West Africa to Ethiopia, encompassing most of the Sahel zone, where habitats range from forest patches and grassland, edges of rainforest and clearings in rainforest mixed with savannah grassland, semi-desert landscape at sea level to montane moorland and dry woodland that is partly flooded during the rainy season from July to December.[19][20][21] Its range has declined in:

- Cameroon, where today lions are present in Bénoué National Park.[22] In the North Province, Cameroon, lions were recorded during a survey between January 2008 and May 2010.[23] The small lion population in Waza National Park is isolated, and by 2008 had declined to maximum 20 individuals.[24]

- the Central African Republic, where the lion population is fragmented to small units in Bamingui-Bangoran National Park and Biosphere Reserve, Manovo-Gounda St. Floris and Awakaba National Parks, Aouk Aoukale, Yata Ngaya, Nana Barya and Zemongo Faunal Reserves, and in several hunting reserves of the country.[25]

- Democratic Republic of Congo in the 1990s during the first and second civil wars.[26]

- Chad, where lions were extirpated in Manda National Park. Some may still be present in pastoral rangelands and mountain ranges outside protected areas. Some persist in Siniaka-Minia Faunal Reserve and Aouk and Zakouma National Parks.[19] The lion population in latter protected area was considered stable in 2013.[27][28] In 2004, the lion population in the country was estimated at maximum 225 individuals.[22]

- Sudan's Southern Darfur province, where lions were abundant in the 1950s; some caused damage to livestock and were poisoned; 76 lions were shot between 1947 and 1952.[29] In the 1980s, lions were also reported in Southern Kordofan province, located west of the Nile River.[19]

- South Sudan, where little is known about lion distribution and population sizes. Lions in Radom and Southern National Parks are probably connected to lions in the Central African Republic.[19]

- Ethiopia since at least the early 20th century due to trophy hunting by Europeans, killing of lions by local people out of fear, for illegal sale of skins and during civil wars.[20]

Contemporary lion distribution and habitat quality in savannahs of West and Central Africa was assessed in 2005, and Lion Conservation Units (LCU) mapped.[30] Educated guesses for size of populations in these LCUs ranged from 2,765 to 2,419 individuals between 2002 and 2012.[19][31]

| Range countries | Lion Conservation Units | Area in km2 |

|---|---|---|

| Cameroon | Waza and Bénoué National Parks | 16,134[32] |

| Central African Republic | eastern part of the country; Bozoum and Nana Barya Faunal Reserves | 339,481[25] |

| Chad | southeastern part | 133,408[31] |

| Democratic Republic of Congo | Garamba-Bili Uere | 115,671[33] |

| South Sudan, Sudan | 331,834[30] | |

| South Sudan, Ethiopia | Boma-Gambella | 106,941[30] |

| Ethiopia | South Omo, Nechisar, Bale, Welmel-Genale, Awash National Parks, Ogaden | 93,274[31] |

| Total | 936,465 |

4. Ecology and Behaviour

In Waza National Park, three female and two male lions were radio-collared in 1999 and tracked until 2001. The females moved in home ranges of between 352 and 724 km2 (136 and 280 sq mi) and stayed inside the park during most of the survey period. The males used home ranges of between 428 and 1,054 km2 (165 and 407 sq mi), both inside and outside the park, where they repeatedly killed livestock. One was killed and the other shot at by local people. After the pellets were removed, he recovered and shifted his home range to inside the park, and was not observed killing livestock any more.[21] Lions probably prey on livestock when wild prey species occur at lower densities, especially during the wet season.[34] An interview survey among livestock owners in six villages in the park's vicinity revealed that lions attack cattle mostly during the rainy season when wild prey disperses away from artificial waterholes.[35]

5. Threats

In Africa, lions are killed pre-emptively or in retaliation for preying on livestock. Populations are also threatened by depletion of prey base, loss and conversion of habitat.[10] The lion population in northern Cameroon is threatened due to increased migration of people from Nigeria following the political insecurity in the region.[24]

6. Conservation

All lion populations in Africa have been included in CITES Appendix II since 1975.[10] In 2006, a Lion Conservation Strategy for West and Central Africa was developed in cooperation between IUCN regional offices and wildlife conservation organisations. The strategy envisages to maintain sufficient habitat, ensure a sufficient wild prey base, make lion-human coexistence sustainable and reduce factors that lead to further fragmentation of populations.[30]

References

- Guggisberg, C. A. W. (1975). "Lion Panthera leo (Linnaeus, 1758)". Wild Cats of the World. New York: Taplinger Publishing. pp. 138–179. ISBN 978-0-8008-8324-9.

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). "Felis Leo" (in Latin). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae: secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Laurentii Salvii). p. 41. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/726936. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Panthera leo". in Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 546. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. http://www.departments.bucknell.edu/biology/resources/msw3/browse.asp?id=14000228.

- Matschie, P. (1900). "Einige Säugethiere aus dem Hinterlande von Kamerun". Sitzungs-Berichte der Gesellschaft der Naturforschender Freunde zu Berlin 3: 87–100.

- Allen, J. A. (1924). "Carnivora Collected By The American Museum Congo Expedition". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 47: 73–281. https://archive.org/stream/bulletinamerican47ameruoft#page/223/mode/2up.

- Allen, G. M. (1939). "A Checklist of African Mammals". Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard College 83: 1–763. https://archive.org/stream/bulletinofmuseum83harv#page/242/mode/2up.

- Hemmer, H. (1974). "Untersuchungen zur Stammesgeschichte der Pantherkatzen (Pantherinae) Teil 3. Zur Artgeschichte des Löwen Panthera (Panthera) leo (Linnaeus, 1758)". Veröffentlichungen der Zoologischen Staatssammlung 17: 167–280. https://archive.org/stream/verfentlichungen171974zool#page/178/mode/2up.

- Pocock, R. I. (1930). "The lions of Asia". Journal of the Bombay Natural Historical Society 34: 638–665.

- Ellerman, J. R.; Morrison-Scott, T. C. S. (1966). Checklist of Palaearctic and Indian mammals 1758 to 1946 (Second ed.). London: British Museum of Natural History. pp. 312–313. https://archive.org/stream/checklistofindia00elle#page/312/mode/2up.

- Template:IUCN doi: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T15951A107265605.en https://doi.org/10.2305%2FIUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T15951A107265605.en

- Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V. et al. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group". Cat News Special Issue 11: 71–73. https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/32616/A_revised_Felidae_Taxonomy_CatNews.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Barnett, R.; Yamaguchi, N.; Barnes, I.; Cooper, A. (2006). "The origin, current diversity and future conservation of the modern lion (Panthera leo)". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 273 (1598): 2119–2125. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3555. PMID 16901830. PMC 1635511. Archived from the original on 8 August 2007. https://web.archive.org/web/20070808182526/http://www.adelaide.edu.au/acad/publications/papers/Barnett%20PRS%20lions.pdf.

- Antunes, A.; Troyer, J. L.; Roelke, M. E.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; Packer, C.; Winterbach, C.; Winterbach, H.; Johnson, W. E. (2008). "The Evolutionary Dynamics of the Lion Panthera leo Revealed by Host and Viral Population Genomics". PLOS Genetics 4 (11): e1000251. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000251. PMID 18989457. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2572142

- Mazák, J.H. (2010). "Geographical variation and phylogenetics of modern lions based on craniometric data". Journal of Zoology. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2010.00694.x. ISSN 09528369. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1469-7998.2010.00694.x

- Bertola, L. D.; Van Hooft, W. F.; Vrieling, K.; Uit De Weerd, D.R.; York, D. S.; Bauer, H.; Prins, H.H.T.; Funston, P.J. et al. (2011). "Genetic diversity, evolutionary history and implications for conservation of the lion (Panthera leo) in West and Central Africa". Journal of Biogeography 38 (7): 1356–1367. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02500.x. http://dspace.learningnetworks.org/bitstream/1820/4311/1/2011_Bertola,Hooft,Vrieling,Weerd,York,Bauer,Prins,Haes,Iongh_GeneticDiversityEvolutionaryHistoryAndImplicationsForConservationOfTheLionInWestAndCentralAfrica.pdf.

- Dubach, J.M., Briggs, M.B., White, P.A., Ament, B.A., & Patterson, B.D. (2013). "Genetic perspectives on “Lion Conservation Units” in Eastern and Southern Africa". Conservation Genetics 14 (4): 741−755.

- Bertola, L.D.; Jongbloed, H.; Van Der Gaag, K.J.; De Knijff, P.; Yamaguchi, N.; Hooghiemstra, H.; Bauer, H.; Henschel, P. et al. (2016). "Phylogeographic patterns in Africa and High Resolution Delineation of genetic clades in the Lion (Panthera leo)". Scientific Reports 6: 30807. doi:10.1038/srep30807. PMID 27488946. PMC 4973251. Bibcode: 2016NatSR...630807B. https://www.nature.com/articles/srep30807?WT.feed_name=subjects_evolution.

- Bruche, S.; Gusset, M.; Lippold, S.; Barnett, R.; Eulenberger, K.; Junhold, J.; Driscoll, C. A.; Hofreiter, M. (2012). "A genetically distinct lion (Panthera leo) population from Ethiopia". European Journal of Wildlife Research 59 (2): 215–225. doi:10.1007/s10344-012-0668-5. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs10344-012-0668-5

- Chardonnet, P. (2002). "Chapter II: Population Survey". Conservation of the African Lion : Contribution to a Status Survey. Paris: International Foundation for the Conservation of Wildlife, France & Conservation Force, USA. pp. 21–101. http://conservationforce.org/pdf/conservationoftheafricanlion.pdf.

- Yalden, D.W., Largen, M.J. & Kock, D. (1980). "Catalogue of the Mammals of Ethiopia". Monitore Zoologico Italiano Supplemento 13 (1): 169−272.

- Bauer, H. and De Iongh, H.H. (2005). "Lion (Panthera leo) home ranges and livestock conflicts in Waza National Park, Cameroon". African Journal of Ecology 43 (3): 208−214.

- Bauer, H.; Van Der Merwe, S. (2004). "Inventory of free-ranging lions Panthera leo in Africa". Oryx 38 (1): 26–31. doi:10.1017/S0030605304000055. https://dx.doi.org/10.1017%2FS0030605304000055

- de Iongh, H.H., Croes, B., Rasmussen, G., Buij, R. and Funston, P. (2011). "The status of cheetah and African wild dog in the Bénoué Ecosystem, North Cameroon". Cat News 55: 29−31. https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/bitstream/handle/1887/18286/CB_2011_Iongh_The_status_of_cheetah.pdf?sequence=2.

- Brugière, D., Chardonnet, B. and Scholte, P. (2015). "Large-scale extinction of large carnivores (lion Panthera leo, cheetah Acinonyx jubatus and wild dog Lycaon pictus) in protected areas of West and Central Africa". Tropical Conservation Science 8 (2): 513-527.

- Mésochina, P., Mamang-Kanga, J.B., Chardonnet, P., Mandjo, Y. and Yaguémé, M. (2010). Statut de conservation du lion (Panthera leo Linnaeus, 1758) en République Centrafricaine. Bangui: Fondation IGF.

- Plumptre, A.J., Kujirakwinja, D., Treves, A., Owiunji, I. and Rainer, H. (2007). "Transboundary conservation in the greater Virunga landscape: its importance for landscape species". Biological Conservation 134 (2): 279−287.

- Vanherle, N. (2011). "Inventaire et suivi de la population de lions (Panthera leo) du Parc National de Zakouma (Tchad)". Revue d’Écologie (La Terre & La Vie) 66: 317−366.

- Olléova, M. and Dogringar, S. (2013). Zakouma National Park: Carnivore monitoring programme. Ndjaména, Chad: African Parks.

- Wilson, R.T. (1979). "Wildlife in Southern Darfur, Sudan: Distribution and status at present and in the recent past". Mammalia 43 (3): 323−338.

- IUCN Cat Specialist Group (2006). Conservation Strategy for the Lion in West and Central Africa. Yaounde, Cameroon: IUCN.

- Riggio, J.; Jacobson, A.; Dollar, L.; Bauer, H.; Becker, M.; Dickman, A.; Funston, P.; Groom, R. et al. (2013). "The size of savannah Africa: a lion's (Panthera leo) view". Biodiversity and Conservation 22 (1): 17–35. doi:10.1007/s10531-012-0381-4. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs10531-012-0381-4

- Tumenta, P.N., Kok, J.S., Van Rijssel, J.C., Buij, R., Croes, B.M., Funston, P.J., De Iongh, H.H. and Udo de Haes, H.A. (2010). "Threat of rapid extermination of the lion (Panthera leo leo) in Waza National Park, Northern Cameroon". African Journal of Ecology 48 (4): 888−894.

- IUCN Cat Specialist Group (2006). Conservation Strategy for the Lion Panthera leo in Eastern and Southern Africa. Pretoria, South Africa: IUCN.

- De Iongh, H, Bauer, H. (2008). "Ten Years of Ecological Research on Lions in Waza National Park, Northern Cameroon". Cat News 48: 29−32.

- Van Bommel, L., Bij de Vaate, M. D., De Boer, W. F., De longh, H. H. (2007). "Factors affecting livestock predation by lions in Cameroon". African Journal of Ecology (45): 490−498.