Scientific evidence indicates that the administration of probiotic bacteria exerts beneficial and protective effects as reduced systemic inflammation, neuroinflammation, and inhibited neurodegeneration. The experimental results performed on animals, but also human clinical trials, show the importance of designing a novel microbiota-based probiotic dietary supplementation with the aim to prevent or ease the symptoms of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases or other forms of dementia or neurodegeneration. The alterations of the gut microbiota, which are called dysbiosis, have been connected with the pathophysiology of numerous common diseases such as type 2 diabetes, obesity, gastrointestinal diseases, and cardiovascular events. Dysbiosis state is also implicated in neurological and neurodegenerative disorders such as autism, and Alzheimer’s (AD) or Parkinson’s (PD) diseases.

- microbiome

- metabolome

- probiotics

- neurodegeneration

- Parkinson’s disease

- Alzheimer’s disease

- gut microbiota

1. Introduction

2. Microbiota–Brain–Gut Axis and Neurodegenerative Diseases/Brain Disorders

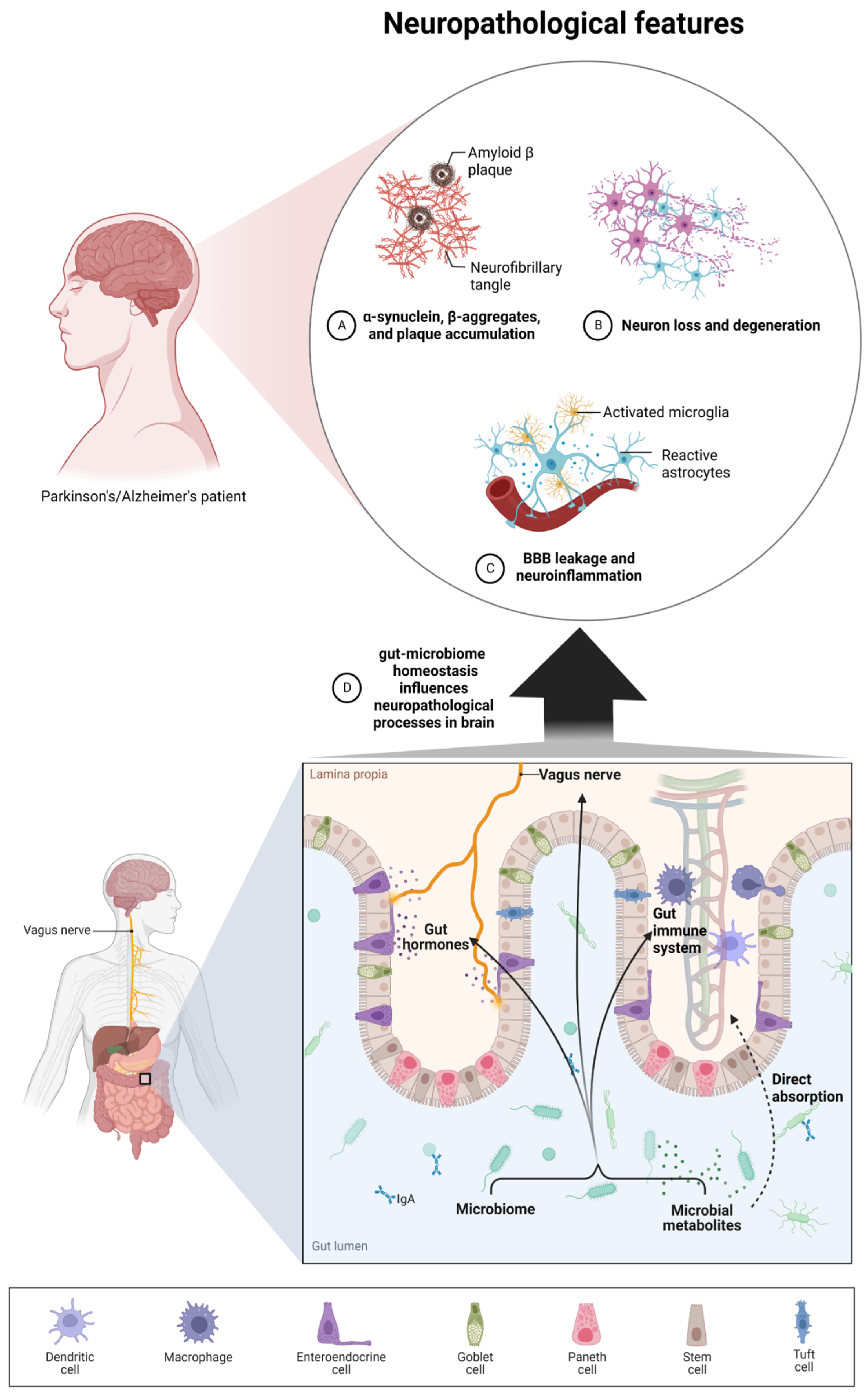

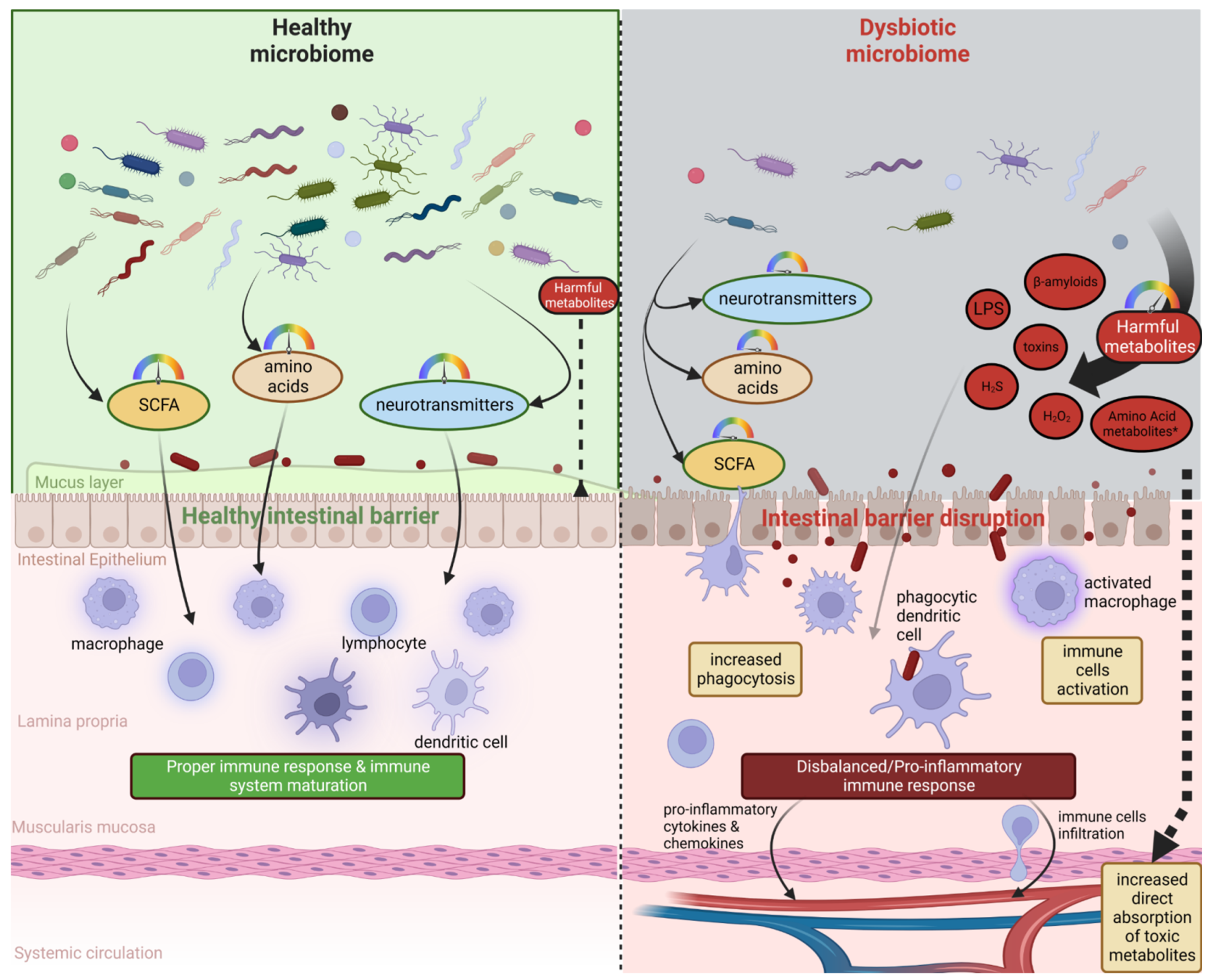

Some research reports underline the crucial role of the microbiome in the normal development, regulation of behavior, cognition, and brain functions, but also in the etiology, the pathogenesis, and the progression of debilitating neurological disorders, e.g., Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, autism spectrum disorder, multiple sclerosis, or even bipolar disorder, depression, schizophrenia, Huntington’s, stroke, and brain ageing [18,20][18][20]. Animal studies have demonstrated the participation of microbiota in neural-related processes such as neurodevelopment, neuroinflammation, interactions with neurons and glia, and behavior [11]. It has been postulated that microbiome influences neurological homeostasis via the microbiome–gut–brain axis. The gut microbiota and brain crosstalk is a complex process including the vagus nerve, the immune system, gut hormone signaling pathways, tryptophan amino acid metabolism, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, and the products of bacterial metabolism such as short-chain fatty acids [21] or gut-derived neurotransmitters [22] (Figure 1). Experimental studies demonstrated that even minor modifications in gut microbiota composition can lead to serious modification of brain functions, subsequently affecting intestinal activity through the secretion of specific hormones, neuropeptides, and neurotransmitters [23]. For example, butyrate, acetate, or propionate can induce the release of leptin and glucagon-like peptide-1, which are the gut hormones interacting with the vagus nerve and brain receptors [24,25,26][24][25][26]. In a mice model, the reduction of the variety of microbiota significantly diminished the blood–brain barrier (BBB) expression of tight junction proteins, occludin and claudin-5, disrupting the barrier function of endothelial cells. Therefore, rodent neural cells become more susceptible to stimuli produced by bacteria, among them lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and factors such as oxidative stress mediators [27]. Moreover, defects in mucosal barrier tight junction proteins increase intestinal permeability, causing the “leaky gut” effect followed by systemic inflammation and pathogenic agents translocation into the bloodstream (e.g., LPS) with elicit pro-inflammatory cytokine release [28,29][28][29]. Aoyama et al. provided evidence of the spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis triggered by butyrate and propionate through a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition, the expression of caspase-3, caspase-8, and caspase-9 pathways, and proteins belonging to the Bcl-2 family, affecting the intestines and different organs. Butyrate and propionate activated neutrophil apoptosis both in the absence and presence of LPS or tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), and therefore in normal and pro-inflammatory conditions. Moreover, the expression of the proapoptotic bax mRNA was significantly elevated and, just the opposite, the expression level of antiapoptotic mcl-1 and a1 mRNA was importantly decreased by the abovementioned SCFAs in non-activated neutrophils. LPS induction highly increased the expression of mcl-1 and a1 mRNA; interestingly, this effect was neutralized by SCFAs [30]. Moreover, clinical trials suggest an altered gut microbial composition of patients with neurodegenerative disorders, together with significant differences in microbial and serum metabolomic profiles [31]. These data indicate that both microbiome composition and microbiome metabolome affect neurological diseases. It is worth mentioning that gut peripheral tissues are a residue for 70% of the human immune system, which is a well-known mediator of changes in gut ecosystem, inflammatory response, and also regulates multiple processes in CNS [32]. A good example of the interplay between gut-located immune cells and brain cells is the influence of regulatory T cells, which exert a neuroprotective effect by stimulating oligodendrocyte differentiation and triggering neuronal remyelination by interleukin IL-10 [19]. At the molecular level, there is evidence that mammalian Toll-Like Receptors (TLRs) play an important role in neurodegeneration. TLRs receptors are one of the main receptor families engaged in transducing and shaping innate immune responses. They are expressed both in immune and non-immune cells, especially increasing after contact with microbial pathogens or bacterial elements, i.e., cell walls, peptidoglycans, or DNA [33]. TLR activation (mainly TLR2 and TLR4) induces an inflammatory response cascade, preceding the neuronal loss characteristic for Parkinson’s disease [34], which could be a result of a “cascade reaction”: disrupted microbial composition and metabolome, increased permeability of the gut cell wall, and increased exposure to TLR ligands. Moreover, the microbiome and its metabolites are associated with immune-mediated neuroinflammation processes, brain injury, and neurogenesis [35]. Microglia cells are brain glial-resident immune cells responsible for maintaining proper immune functions including phagocytosis, antigen presentation, the production of cytokines, and the subsequent inflammatory reactions [36,37][36][37]. Research reports indicate the influence of microbiota on microglial maturation and function; however, this mechanism is still unclear [38]. It has been confirmed that gut dysbiosis can augment intestinal permeability and bacterial translocation, causing an over-response of the immune system and the subsequent systemic/central nervous system inflammation [39,40][39][40]. The adaptive immune system also participates in the regulation of healthy microbiota. The crucial players in intestinal homeostasis maintenance are B cells, which produce secretory IgA antibodies targeted toward specific bacteria [41]. Additionally, gut microbiota can stably influence the host’s gene expression through epigenetic mechanisms, including histone modifications, methylation of DNA, and non-coding RNA expression [42]. Overall, the microbiome plays a big role in moderating the maturation of immune cells residing in the CNS tissues via an interplay and crosstalk with the peripheral immune system. Gut microbiota act as a multifunctional hub modulating the immune system via the production of immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory signaling molecules, reaching immune cells. Commensal microbes fabricate various metabolites from digested food, SCFAs among them, which participate in the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis, exerting anti-inflammatory activity on the intestinal mucosa [43]. The gut microbiota participates in signal transduction pathways as it can communicate between the host’s innate immune system cells, which are located at the interface between the host and the microbiome [44].

3. Microbiota Metabolites and the Severity of Neurodegenerative Diseases

4. Nutritional Intervention as a Promising Solution to Prevent the Progression of Neurodegenerative Diseases

Currently, wresearchers have defined multiple factors which have an influence on the microbiome’s composition and its metabolome, i.e., environmental (such as exposure to pesticides or heavy metals), biological (infections), and sociodemographic factors such as inadequate diet, stress, mode of delivery at birth, lack of breastfeeding during the neonatal period, or antibiotic therapy [161,188,189][62][63][64]. All of these factors could negatively modulate the microbiome and finally lead to dysbiosis. However, if wresearchers try to indicate the most powerful factor, then diet is one of the strongest lifetime modulators of microbiome composition [190,191][65][66]. For example, the Western diet is a well-known negative modifier of microbiome composition and a promoting factor of multiple common diseases [192][67]. It is characterized by high fat and sugar ingestion and low fiber content, which are positively linked to Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria abundance, but negatively correlated with fiber-rich nourishment. A contradictory connotation could be observed for Proteobacteria and Firmicutes [193][68]. Contrarily, as a positive example, balanced diets (i.e., Mediterranean diet and Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) can be mentioned. Diets abundant in natural compounds with anti-inflammatory activity, antioxidants, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and plant-origin nutrients (proteins, polyphenols, vitamins, and fibers), together with reduced caloric intake, such as the Mediterranean diet, are correlated with a lower risk of dementia, decrease age-related cognitive deterioration, and the risk of neurodegeneration occurrence [194,195,196][69][70][71]. Moreover, the Mediterranean diet increases the amount of gut Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus and reduces malignant bacteria belonging to Clostridium and Bacteroides, thereby improving memory and cognitive processes in healthy females after menopause and disorder patients. Additionally, following such a diet significantly reduces amyloid aggregation and therefore the frequency of amyloid-related diseases in the aging population [14,197,198][14][72][73]. There are scientific reports that he gut dysfunction is related to the inflammation of the CNS, which can especially be observed in Parkinson’s disease patients, where dysregulation of the gut–brain axis was observed in 80% of patients [199][74]. In the past decade, single dietary factors which can positively manipulate the gut microbiota–brain axis through microbiome modulation have gained significant attention [200,201][75][76]. One of these factors is probiotic bacteria and/or prebiotics. Probiotics are defined as microbial organisms with a beneficial role in the host’s health and homeostasis, which help to preserve digestive, metabolic, immune, and neuroendocrine functions [202][77]. Naturally probiotic bacteria can be found in fermented food [203,204][78][79]. Experimental results revealed that the administration of probiotics alone or in combination with prebiotics (fructooligosaccharides or galactooligosaccharides) improved the gastrointestinal barrier [205[80][81],206], which is the first line of “defence” from harmful factors occurring in food, and the microbiome. Probiotics and prebiotics are well-documented “problem-solution” for gastrointestinal diseases [207,208][82][83]. Moreover, probiotics can reduce CNS inflammatory processes and activation of microglia, demonstrating promising potential for use in neurodegenerative diseases as ingestible “psychobiotics”. Many studies indicate that the ingestion of probiotics can serve as a microbiological strategy against neurodegenerative diseases such as AD [209,210,211][84][85][86]; however, the exact mechanism is under investigation [212][87]. Experiments performed on mice underline the hypothesis that mechanisms related to neuroprotective effects of Bifidobacterium breve administration may be connected with neuroinflammation and cognition pathways, probably through the production of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) neurotransmitter and the regulation of the gut microbial composition [213][88]. Clinical results of a randomized double-blind controlled trial revealed that 3-month exposure to Lactobacillus spp. And a Bifidobacterium bifidum “cocktail” enhanced cognitive functions and memory, as examined in a mini-mental state test [214][89]. It was demonstrated that Bifidobacterium breve exerts positive and unique activity in AD patients, improving cognitive functions and reducing neuroinflammation. Controlled, double-blind, randomized clinical trials with a 12-week multispecies probiotic treatment (comprised of Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus casei, Bifidobacterium bifidum, and Lactobacillus fermentum) caused a significant decrease in malondialdehyde in the probiotic-treated group [214][89].References

- Qin, J.; Li, R.; Raes, J.; Arumugam, M.; Burgdorf, K.S.; Manichanh, C.; Nielsen, T.; Pons, N.; Levenez, F.; Yamada, T.; et al. A Human Gut Microbial Gene Catalogue Established by Metagenomic Sequencing. Nature 2010, 464, 59–65.

- Stilling, R.M.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Microbial Genes, Brain & Behaviour—Epigenetic Regulation of the Gut-Brain Axis. Genes Brain Behav. 2014, 13, 69–86.

- Zhu, S.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, K.; Cui, M.; Ye, W.; Zhao, G.; Jin, L.; Chen, X. The Progress of Gut Microbiome Research Related to Brain Disorders. J. Neuroinflamm. 2020, 17, 25.

- Blum, H.E. The Human Microbiome. Adv. Med. Sci. 2017, 62, 414–420.

- Dingeo, G.; Brito, A.; Samouda, H.; Iddir, M.; La Frano, M.R.; Bohn, T. Phytochemicals as Modifiers of Gut Microbial Communities. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 8444–8471.

- Conlon, M.A.; Bird, A.R. The Impact of Diet and Lifestyle on Gut Microbiota and Human Health. Nutrients 2014, 7, 17–44.

- Structure, Function and Diversity of the Healthy Human Microbiome. Nature 2012, 486, 207–214.

- Le Chatelier, E.; Nielsen, T.; Qin, J.; Prifti, E.; Hildebrand, F.; Falony, G.; Almeida, M.; Arumugam, M.; Batto, J.-M.; Kennedy, S.; et al. Richness of Human Gut Microbiome Correlates with Metabolic Markers. Nature 2013, 500, 541–546.

- Jiang, C.; Li, G.; Huang, P.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, B. The Gut Microbiota and Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017, 58, 1–15.

- Hooper, L.V.; Gordon, J.I. Commensal Host-Bacterial Relationships in the Gut. Science 2001, 292, 1115–1118.

- Cryan, J.F.; O’Riordan, K.J.; Sandhu, K.; Peterson, V.; Dinan, T.G. The Gut Microbiome in Neurological Disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 179–194.

- Sun, M.-F.; Shen, Y.-Q. Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota and Microbial Metabolites in Parkinson’s Disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2018, 45, 53–61.

- Westfall, S.; Lomis, N.; Kahouli, I.; Dia, S.Y.; Singh, S.P.; Prakash, S. Microbiome, Probiotics and Neurodegenerative Diseases: Deciphering the Gut Brain Axis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 3769–3787.

- Pellegrini, C.; Antonioli, L.; Colucci, R.; Blandizzi, C.; Fornai, M. Interplay among Gut Microbiota, Intestinal Mucosal Barrier and Enteric Neuro-Immune System: A Common Path to Neurodegenerative Diseases? Acta Neuropathol. 2018, 136, 345–361.

- Levy, M.; Thaiss, C.A.; Elinav, E. Metabolites: Messengers between the Microbiota and the Immune System. Genes Dev. 2016, 30, 1589–1597.

- Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, Y. Regulation of Neurotransmitters by the Gut Microbiota and Effects on Cognition in Neurological Disorders. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2099.

- Wang, Y.; Xu, E.; Musich, P.R.; Lin, F. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Neurodegenerative Diseases and the Potential Countermeasure. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2019, 25, 816–824.

- Konjevod, M.; Nikolac Perkovic, M.; Sáiz, J.; Svob Strac, D.; Barbas, C.; Rojo, D. Metabolomics Analysis of Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Neurodegenerative and Psychiatric Diseases. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2021, 194, 113681.

- Hirschberg, S.; Gisevius, B.; Duscha, A.; Haghikia, A. Implications of Diet and The Gut Microbiome in Neuroinflammatory and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3109.

- Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. The Microbiome-Gut-Brain Axis in Health and Disease. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 46, 77–89.

- Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Gut Instincts: Microbiota as a Key Regulator of Brain Development, Ageing and Neurodegeneration. J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 489–503.

- Wang, S.; Cui, W.; Zeng, M.; Ren, Y.; Han, S.; Li, J. The Increased Release of Amino Acid Neurotransmitters of the Primary Somatosensory Cortical Area in Rats Contributes to Remifentanil-Induced Hyperalgesia and Its Inhibition by Lidocaine. J. Pain Res. 2018, 11, 1521–1529.

- Santoro, A.; Ostan, R.; Candela, M.; Biagi, E.; Brigidi, P.; Capri, M.; Franceschi, C. Gut Microbiota Changes in the Extreme Decades of Human Life: A Focus on Centenarians. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 129–148.

- Strandwitz, P. Neurotransmitter Modulation by the Gut Microbiota. Brain Res. 2018, 1693, 128–133.

- Tolhurst, G.; Heffron, H.; Lam, Y.S.; Parker, H.E.; Habib, A.M.; Diakogiannaki, E.; Cameron, J.; Grosse, J.; Reimann, F.; Gribble, F.M. Short-Chain Fatty Acids Stimulate Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Secretion via the G-Protein–Coupled Receptor FFAR2. Diabetes 2012, 61, 364–371.

- Everard, A.; Lazarevic, V.; Gaïa, N.; Johansson, M.; Ståhlman, M.; Backhed, F.; Delzenne, N.M.; Schrenzel, J.; François, P.; Cani, P.D. Microbiome of Prebiotic-Treated Mice Reveals Novel Targets Involved in Host Response during Obesity. ISME J. 2014, 8, 2116–2130.

- Braniste, V.; Al-Asmakh, M.; Kowal, C.; Anuar, F.; Abbaspour, A.; Tóth, M.; Korecka, A.; Bakocevic, N.; Ng, L.G.; Kundu, P.; et al. The Gut Microbiota Influences Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability in Mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 263ra158.

- Arrona Cardoza, P.; Spillane, M.B.; Morales Marroquin, E. Alzheimer’s Disease and Gut Microbiota: Does Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) Play a Role? Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 271–281.

- Spielman, L.J.; Gibson, D.L.; Klegeris, A. Unhealthy Gut, Unhealthy Brain: The Role of the Intestinal Microbiota in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Neurochem. Int. 2018, 120, 149–163.

- Aoyama, M.; Kotani, J.; Usami, M. Butyrate and Propionate Induced Activated or Non-Activated Neutrophil Apoptosis via HDAC Inhibitor Activity but without Activating GPR-41/GPR-43 Pathways. Nutrition 2010, 26, 653–661.

- Padhi, P.; Worth, C.; Zenitsky, G.; Jin, H.; Sambamurti, K.; Anantharam, V.; Kanthasamy, A.; Kanthasamy, A.G. Mechanistic Insights Into Gut Microbiome Dysbiosis-Mediated Neuroimmune Dysregulation and Protein Misfolding and Clearance in the Pathogenesis of Chronic Neurodegenerative Disorders. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 836605.

- Kesika, P.; Suganthy, N.; Sivamaruthi, B.S.; Chaiyasut, C. Role of Gut-Brain Axis, Gut Microbial Composition, and Probiotic Intervention in Alzheimer’s Disease. Life Sci. 2021, 264, 118627.

- Mogensen, T.H. Pathogen Recognition and Inflammatory Signaling in Innate Immune Defenses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 22, 240–273.

- Drouin-Ouellet, J.; Cicchetti, F. Inflammation and Neurodegeneration: The Story “Retolled”. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2012, 33, 542–551.

- Juźwik, C.A.; Drake, S.S.; Zhang, Y.; Paradis-Isler, N.; Sylvester, A.; Amar-Zifkin, A.; Douglas, C.; Morquette, B.; Moore, C.S.; Fournier, A.E. microRNA Dysregulation in Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Systematic Review. Prog. Neurobiol. 2019, 182, 101664.

- Nayak, D.; Roth, T.L.; McGavern, D.B. Microglia Development and Function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 32, 367–402.

- Nayak, D.; Zinselmeyer, B.H.; Corps, K.N.; McGavern, D.B. In Vivo Dynamics of Innate Immune Sentinels in the CNS. Intravital 2012, 1, 95–106.

- Erny, D.; Hrabě de Angelis, A.L.; Jaitin, D.; Wieghofer, P.; Staszewski, O.; David, E.; Keren-Shaul, H.; Mahlakoiv, T.; Jakobshagen, K.; Buch, T.; et al. Host Microbiota Constantly Control Maturation and Function of Microglia in the CNS. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 965–977.

- Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G. Mind-Altering Microorganisms: The Impact of the Gut Microbiota on Brain and Behaviour. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 13, 701–712.

- Caputi, V.; Giron, M.C. Microbiome-Gut-Brain Axis and Toll-Like Receptors in Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1689.

- Peterson, D.A.; McNulty, N.P.; Guruge, J.L.; Gordon, J.I. IgA Response to Symbiotic Bacteria as a Mediator of Gut Homeostasis. Cell Host Microbe 2007, 2, 328–339.

- Nichols, R.G.; Davenport, E.R. The Relationship between the Gut Microbiome and Host Gene Expression: A Review. Hum. Genet. 2021, 140, 747–760.

- Ferreira, C.M.; Vieira, A.T.; Vinolo, M.A.R.; Oliveira, F.A.; Curi, R.; Martins, F. dos S. The Central Role of the Gut Microbiota in Chronic Inflammatory Diseases. J. Immunol. Res. 2014, 2014, 689492.

- Thaiss, C.A.; Zmora, N.; Levy, M.; Elinav, E. The Microbiome and Innate Immunity. Nature 2016, 535, 65–74.

- Doifode, T.; Giridharan, V.V.; Generoso, J.S.; Bhatti, G.; Collodel, A.; Schulz, P.E.; Forlenza, O.V.; Barichello, T. The Impact of the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis on Alzheimer’s Disease Pathophysiology. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 164, 105314.

- Zhao, Y.; Jaber, V.; Lukiw, W.J. Secretory Products of the Human GI Tract Microbiome and Their Potential Impact on Alzheimer’s Disease (AD): Detection of Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in AD Hippocampus. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 318.

- Whitfield, C.; Trent, M.S. Biosynthesis and Export of Bacterial Lipopolysaccharides. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2014, 83, 99–128.

- Wu, L.; Han, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Peng, G.; Liu, P.; Yue, S.; Zhu, S.; Chen, J.; Lv, H.; Shao, L.; et al. Altered Gut Microbial Metabolites in Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease: Signals in Host-Microbe Interplay. Nutrients 2021, 13, 228.

- Lamkanfi, M.; Dixit, V.M. Mechanisms and Functions of Inflammasomes. Cell 2014, 157, 1013–1022.

- Jia, W.; Rajani, C.; Kaddurah-Daouk, R.; Li, H. Expert Insights: The Potential Role of the Gut Microbiome-Bile Acid-Brain Axis in the Development and Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease and Hepatic Encephalopathy. Med. Res. Rev. 2020, 40, 1496–1507.

- Samsel, A.; Seneff, S. Glyphosate’s Suppression of Cytochrome P450 Enzymes and Amino Acid Biosynthesis by the Gut Microbiome: Pathways to Modern Diseases. Entropy 2013, 15, 1416–1463.

- Jiang, H.; Ling, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Mao, H.; Ma, Z.; Yin, Y.; Wang, W.; Tang, W.; Tan, Z.; Shi, J.; et al. Altered Fecal Microbiota Composition in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Brain Behav. Immun. 2015, 48, 186–194.

- Venegas, D.P.; De la Fuente, M.K.; Landskron, G.; González, M.J.; Quera, R.; Dijkstra, G.; Harmsen, H.J.M.; Faber, K.N.; Hermoso, M.A. Short Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)-Mediated Gut Epithelial and Immune Regulation and Its Relevance for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 277.

- Tan, J.; McKenzie, C.; Potamitis, M.; Thorburn, A.N.; Mackay, C.R.; Macia, L. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Health and Disease. Adv. Immunol. 2014, 121, 91–119.

- Tagliabue, A.; Elli, M. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Human Obesity: Recent Findings and Future Perspectives. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2013, 23, 160–168.

- Dalile, B.; Van Oudenhove, L.; Vervliet, B.; Verbeke, K. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Microbiota–gut–brain Communication. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 461–478.

- Chen, S.-J.; Chen, C.-C.; Liao, H.-Y.; Lin, Y.-T.; Wu, Y.-W.; Liou, J.-M.; Wu, M.-S.; Kuo, C.-H.; Lin, C.-H. Association of Fecal and Plasma Levels of Short-Chain Fatty Acids with Gut Microbiota and Clinical Severity in Patients With Parkinson Disease. Neurology 2022, 98, e848–e858.

- Verbeke, K.A.; Boobis, A.R.; Chiodini, A.; Edwards, C.A.; Franck, A.; Kleerebezem, M.; Nauta, A.; Raes, J.; van Tol, E.A.F.; Tuohy, K.M. Towards Microbial Fermentation Metabolites as Markers for Health Benefits of Prebiotics. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2015, 28, 42–66.

- Galland, L. The Gut Microbiome and the Brain. J. Med. Food 2014, 17, 1261–1272.

- Canfora, E.E.; Jocken, J.W.; Blaak, E.E. Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Control of Body Weight and Insulin Sensitivity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2015, 11, 577–591.

- Goyal, D.; Ali, S.A.; Singh, R.K. Emerging Role of Gut Microbiota in Modulation of Neuroinflammation and Neurodegeneration with Emphasis on Alzheimer’s Disease. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 106, 110112.

- Kong, G.; Ellul, S.; Narayana, V.K.; Kanojia, K.; Ha, H.T.T.; Li, S.; Renoir, T.; Cao, K.-A.L.; Hannan, A.J. An Integrated Metagenomics and Metabolomics Approach Implicates the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in the Pathogenesis of Huntington’s Disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021, 148, 105199.

- Howarth, G.S.; Wang, H. Role of Endogenous Microbiota, Probiotics and Their Biological Products in Human Health. Nutrients 2013, 5, 58–81.

- Ajslev, T.A.; Andersen, C.S.; Gamborg, M.; Sørensen, T.I.A.; Jess, T. Childhood Overweight after Establishment of the Gut Microbiota: The Role of Delivery Mode, Pre-Pregnancy Weight and Early Administration of Antibiotics. Int. J. Obes. 2011, 35, 522–529.

- Davis, E.C.; Dinsmoor, A.M.; Wang, M.; Donovan, S.M. Microbiome Composition in Pediatric Populations from Birth to Adolescence: Impact of Diet and Prebiotic and Probiotic Interventions. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2020, 65, 706–722.

- Kashtanova, D.A.; Popenko, A.S.; Tkacheva, O.N.; Tyakht, A.B.; Alexeev, D.G.; Boytsov, S.A. Association between the Gut Microbiota and Diet: Fetal Life, Early Childhood, and Further Life. Nutrition 2016, 32, 620–627.

- Statovci, D.; Aguilera, M.; MacSharry, J.; Melgar, S. The Impact of Western Diet and Nutrients on the Microbiota and Immune Response at Mucosal Interfaces. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 838.

- Wu, G.D.; Chen, J.; Hoffmann, C.; Bittinger, K.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Keilbaugh, S.A.; Bewtra, M.; Knights, D.; Walters, W.A.; Knight, R.; et al. Linking Long-Term Dietary Patterns with Gut Microbial Enterotypes. Science 2011, 334, 105–108.

- Sofi, F.; Macchi, C.; Casini, A. Mediterranean Diet and Minimizing Neurodegeneration. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2013, 2, 75–80.

- Féart, C.; Samieri, C.; Rondeau, V.; Amieva, H.; Portet, F.; Dartigues, J.-F.; Scarmeas, N.; Barberger-Gateau, P. Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet, Cognitive Decline, and Risk of Dementia. JAMA 2009, 302, 638–648.

- Liu, X.; Morris, M.C.; Dhana, K.; Ventrelle, J.; Johnson, K.; Bishop, L.; Hollings, C.S.; Boulin, A.; Laranjo, N.; Stubbs, B.J.; et al. Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) Study: Rationale, Design and Baseline Characteristics of a Randomized Control Trial of the MIND Diet on Cognitive Decline. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2021, 102, 106270.

- Joseph, J.; Cole, G.; Head, E.; Ingram, D. Nutrition, Brain Aging, and Neurodegeneration. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 12795–12801.

- van de Rest, O.; Berendsen, A.A.; Haveman-Nies, A.; de Groot, L.C. Dietary Patterns, Cognitive Decline, and Dementia: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. 2015, 6, 154–168.

- Mulak, A.; Bonaz, B. Brain-Gut-Microbiota Axis in Parkinson’s Disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 10609–10620.

- Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Gut-Brain Axis in 2016: Brain-Gut-Microbiota Axis—Mood, Metabolism and Behaviour. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 69–70.

- Hori, T.; Matsuda, K.; Oishi, K. Probiotics: A Dietary Factor to Modulate the Gut Microbiome, Host Immune System, and Gut–Brain Interaction. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1401.

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. Expert Consensus Document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics Consensus Statement on the Scope and Appropriate Use of the Term Probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514.

- Ravishankar, R.V.; Bai, J.A. Beneficial Microbes in Fermented and Functional Foods; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; ISBN 9781482206623.

- Fuloria, S.; Mehta, J.; Talukdar, M.P.; Sekar, M.; Gan, S.H.; Subramaniyan, V.; Rani, N.N.I.M.; Begum, M.Y.; Chidambaram, K.; Nordin, R.; et al. Synbiotic Effects of Fermented Rice on Human Health and Wellness: A Natural Beverage That Boosts Immunity. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 950913.

- Gill, H.S.; Rutherfurd, K.J.; Cross, M.L.; Gopal, P.K. Enhancement of Immunity in the Elderly by Dietary Supplementation with the Probiotic Bifidobacterium Lactis HN019. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 74, 833–839.

- Vulevic, J.; Drakoularakou, A.; Yaqoob, P.; Tzortzis, G.; Gibson, G.R. Modulation of the Fecal Microflora Profile and Immune Function by a Novel Trans-Galactooligosaccharide Mixture (B-GOS) in Healthy Elderly Volunteers. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 1438–1446.

- Floch, M.H.; Ringel, Y.; Allen Walker, W. The Microbiota in Gastrointestinal Pathophysiology: Implications for Human Health, Prebiotics, Probiotics, and Dysbiosis; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 9780128040621.

- Hojsak, I.; Kolaček, S.; Mihatsch, W.; Mosca, A.; Shamir, R.; Szajewska, H.; Vandenplas, Y. Working Group on Probiotics and Prebiotics of the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition* Synbiotics in The Management of Pediatric Gastrointestinal Disorders: Position Paper of the Espghan Special Interest Group on Gut Microbiota and Modifications. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2022.

- Plaza-Díaz, J.; Ruiz-Ojeda, F.J.; Vilchez-Padial, L.M.; Gil, A. Evidence of the Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Probiotics and Synbiotics in Intestinal Chronic Diseases. Nutrients 2017, 9, 555.

- Tamtaji, O.R.; Heidari-Soureshjani, R.; Mirhosseini, N.; Kouchaki, E.; Bahmani, F.; Aghadavod, E.; Tajabadi-Ebrahimi, M.; Asemi, Z. Probiotic and Selenium Co-Supplementation, and the Effects on Clinical, Metabolic and Genetic Status in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Trial. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 2569–2575.

- Kobayashi, Y.; Kinoshita, T.; Matsumoto, A.; Yoshino, K.; Saito, I.; Xiao, J.-Z. Bifidobacterium Breve A1 Supplementation Improved Cognitive Decline in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment: An Open-Label, Single-Arm Study. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019, 6, 70–75.

- Ansari, F.; Pourjafar, H.; Tabrizi, A.; Homayouni, A. The Effects of Probiotics and Prebiotics on Mental Disorders: A Review on Depression, Anxiety, Alzheimer, and Autism Spectrum Disorders. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2020, 21, 555–565.

- Zhu, G.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Wang, G. Administration of Bifidobacterium Breve Improves the Brain Function of Aβ1-42-Treated Mice via the Modulation of the Gut Microbiome. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1602.

- Akbari, E.; Asemi, Z.; Daneshvar Kakhaki, R.; Bahmani, F.; Kouchaki, E.; Tamtaji, O.R.; Hamidi, G.A.; Salami, M. Effect of Probiotic Supplementation on Cognitive Function and Metabolic Status in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Randomized, Double-Blind and Controlled Trial. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2016, 8, 256.