Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by HARSH KUMAR and Version 2 by Dean Liu.

The thiazolidin-2,4-dione (TZD) moiety plays a central role in the biological functioning of several essential molecules. The availability of substitutions at the third and fifth positions of the Thiazolidin-2,4-dione (TZD) scaffold makes it a highly utilized and versatile moiety that exhibits a wide range of biological activities.

- thiazolidin-2,4-dione derivatives

- antimicrobial activity

- antioxidant activity

1. Introduction

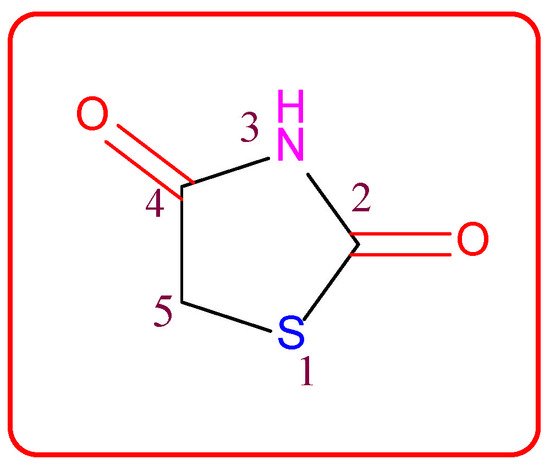

Small heterocyclic structures containing nitrogen and sulfur have been under investigation for a long time owing to their therapeutic relevance. They offer a wide range of structural varieties and also possess a proven range of diversified therapeutic potentials. Amongst the extensive variety of heterocyclic scaffolds explored in the search for potent bioactive molecules in the process of drug discovery, the thiazolidin-2,4-dione (TZD) (Figure 1) ring system has been acknowledged as a significant scaffold in medicinal chemistry [1].

Figure 1. Structure of the thiazolidine-2,4-dione scaffold.

Thiazolidin-2,4-dione (Figure 1), also called glitazone, is a heterocyclic moiety that consists of a five-membered saturated thiazolidine ring with sulfur at 1 and nitrogen at 3, along with two carbonyl functional groups at the 2 and 4 positions. Substitutions of various moieties are possible only at the third and fifth positions of the Thiazolidin-2,4-dione (TZD) scaffold. The analogues of TZD offer a wide range of structural varieties [2] and also possess a proven range of diversified therapeutic potentials, such as antidiabetic [3][4][5][3,4,5], analgesic, anti-inflammatory [6][7][8][6,7,8], wound healing [9], antiproliferative [10][11][12][13][14][10,11,12,13,14], antimalarial [15], antitubercular [16][17][16,17], hypolipidemic [18], antiviral [19], antimicrobial, antifungal [20][21][22][23][20,21,22,23], and antioxidant properties [24][25][24,25], etc.

2. The History of Glitazones as Antidiabetics

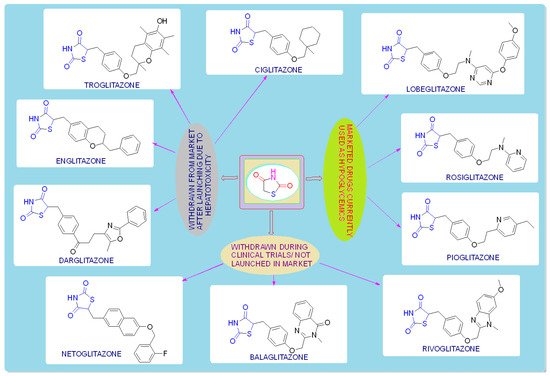

TZDs are primarily used as hypoglycemic agents over a long time. Ciglitazone is the prototype of the TZD class, which was developed by Takeda Pharmaceuticals (Japan) in the early 1980s but has never been used as a medication due to its hepatotoxicity. In the year 1988, another TZD analog, named troglitazone, was developed by the Sankyo Company (Japan) as an antidiabetic agent, but it was also banned in the year 2000 due to its hepatic toxicity. In 1999, Pfizer (USA) and Takeda (Japan) jointly developed two molecules, pioglitazone (patented in 2002), and englitazone, and subsequently, Pfizer and Smithkline also developed rosiglitazone and darglitazone in the same year. Englitazone and darglitazone were discontinued due to their hepatotoxicity. However, pioglitazone was reported to be safe for use in the hepatic system and is currently in use as an antidiabetic agent. In 2001, rosiglitazone was reported to cause heart failure due to fluid retention and, hence, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) restricted its use in the year 2010. However, in the year 2013, the restriction was removed by the FDA after a series of trials proved that there was no effect on the heart due to fluid retention. Another drug, lobeglitazone, was developed by Chong Kun Dang Pharmaceuticals (Korea) in 2013, which was approved by the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety of Korea. Some other molecules, such as netaglitazone, rivoglitazone, and balaglitazone, were also developed but then withdrawn during the clinical trial due to their severe toxicities, and these never came to the market. The structures of various TZDs are shown in Figure 2 [26][27][26,27].

Figure 2. Antidiabetic molecules developed with the thiazolidin-2,4-dione moiety.

3. Mechanism of Action

TZDs produce their biological response by stimulating the PPARγ receptor (antidiabetic activity) and cytoplasmic Mur ligase enzyme (antimicrobial activity), and by scavenging ROS (antioxidant activity).-

Family of PPARs:

-

Isoforms of PPARs:

-

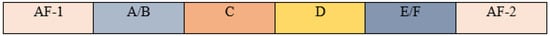

Structure and biological functions of PPARs:

Figure 3. Principal functional domains of PPARs.

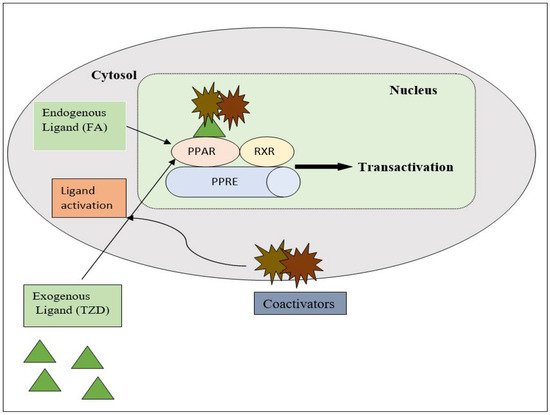

3.1. Mechanism of the TZD as an Antidiabetic

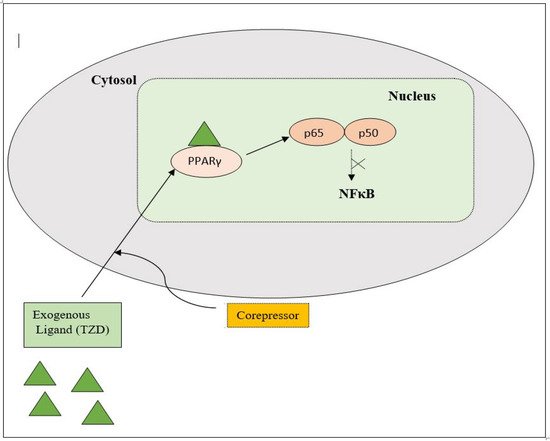

PPAR acts by either transactivation or by trans-repression to enact its antidiabetic activity. In transactivation, PPAR is activated upon binding with the exogenous ligand (TZD) or endogenous ligands (PGs, fatty acids, etc.). PPAR then heterodimerizes with the retinoid X factor (RXR) to form the PPAR–RXR complex. This complex binds with peroxisome proliferator response elements (PPRE) in the target gene with a coactivator that has histone acetylase activity and promotes the transcription of different genes involved in the cellular differentiation and glucose and lipid metabolism (Figure 4) [26][28][26,28]. In trans-repression, PPARs interact negatively with other signal transduction pathways, such as the nuclear factor kappa beta (NFκB) pathway, which controls various genes involved in inflammation and also regulates inflammatory mediators, such as leukocytes and cytokines, etc. (Figure 5) [28].

Figure 4. Gene transcription mechanisms of PPAR.

Figure 5. Gene trans-repression mechanisms of PPAR.

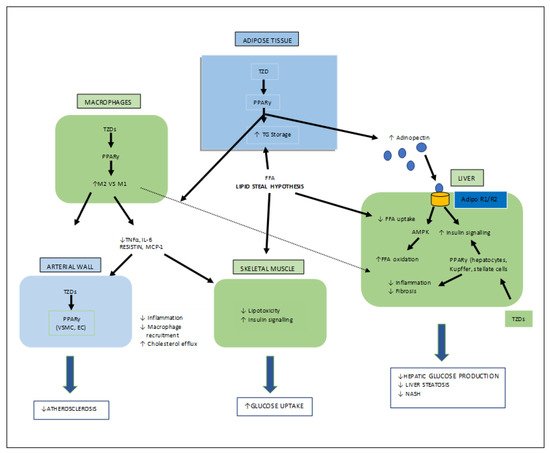

Figure 6. Various target organs/sites of TZD-PPARγ.

3.2. Mechanism of TZD as Antimicrobial Agent

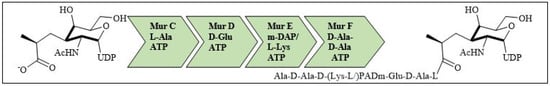

For bacterial viability, the bacterial cell wall is an important component in maintaining the cell shape and protection. Peptidoglycan is one of the major constituents of the bacterial cell wall and is found on the outer wall of cytoplasmic membrane. Its biosynthetic enzyme inhibition can lead to cell death. The enzymes involved in the synthesis can either be membrane-bound extracellular enzymes (penicillin-binding proteins) or cytoplasmic enzymes (Mur enzymes). Peptidoglycan peptide stem biosynthesis involves four ATP-dependent enzymes, known as the Mur ligases (Mur C-F). They mediate the formation of UDP-MurNAc-pentapeptide through the stepwise additions of MurC (L-alanine), MurD (D-glutamic acid), a diamino acid which is generally a meso-diaminopimelic acid, or MurE (L-lysine) and MurF (dipeptide D-Ala-D-Ala) to the D-lactoyl group of UDP-N-acetylmuramic acid (Figure 7). TZD molecules are supposed to inhibit these cytoplasmic ligases and, hence, lead to bacterial cell death [34][35][36][37][34,35,36,37].

Figure 7. Peptidoglycan peptide stem formation by the Mur ligases enzymes.

3.3. Mechanism of TZD as an Antioxidant

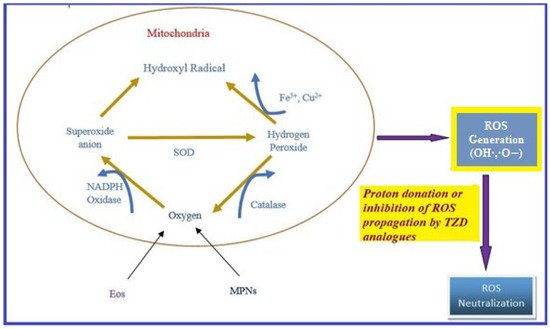

Oxidative stress occurs due to the production of free radicals. Free radicals are chemically active molecules which are either deficient or have a greater number of electrons. Free radicals containing oxygen are the most significant free radicals, also known as reactive oxygen species (ROS). Oxidants activate various relevant enzymes, such as SOD, catalase, and NADPH oxidase, to convert the oxygen to ROS. ROS scavenge body cells in order to capture or donate protons, thus causing cell, proteins, and DNA damage. TZD derivatives are supposed to work by preventing the cascade effect produced through ROS propagation by donating its proton to the ROS (Figure 8) [38][39][40][38,39,40].

Figure 8. ROS generation and antioxidant scavenging mechanism of TZDs.