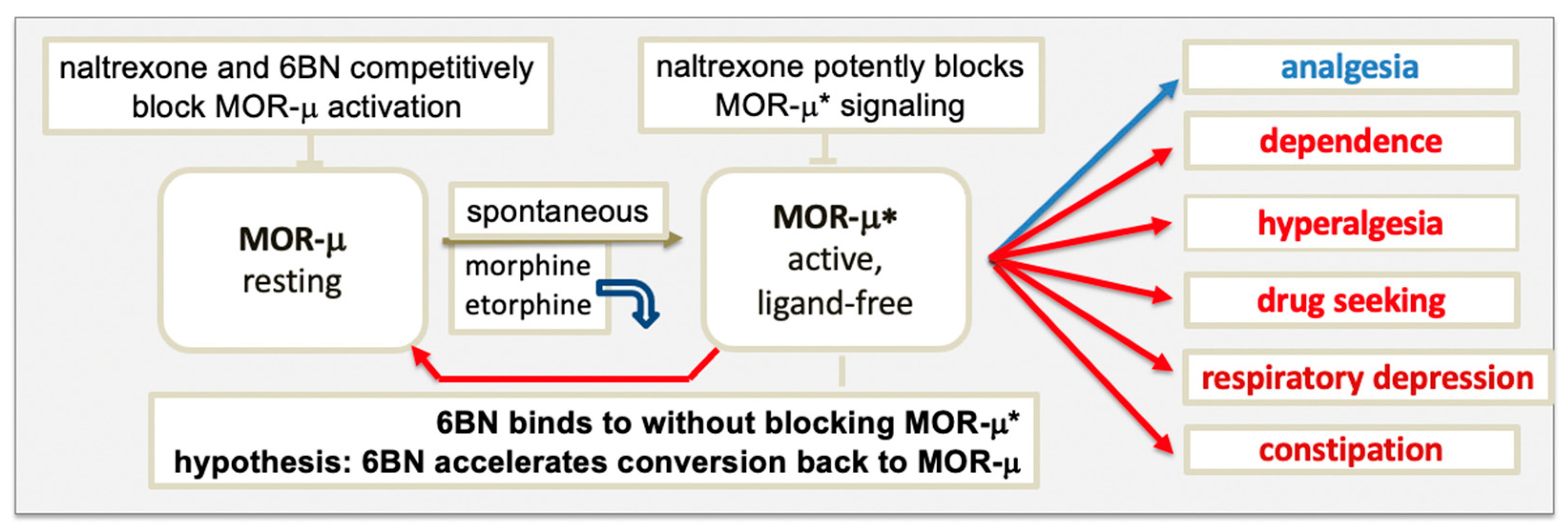

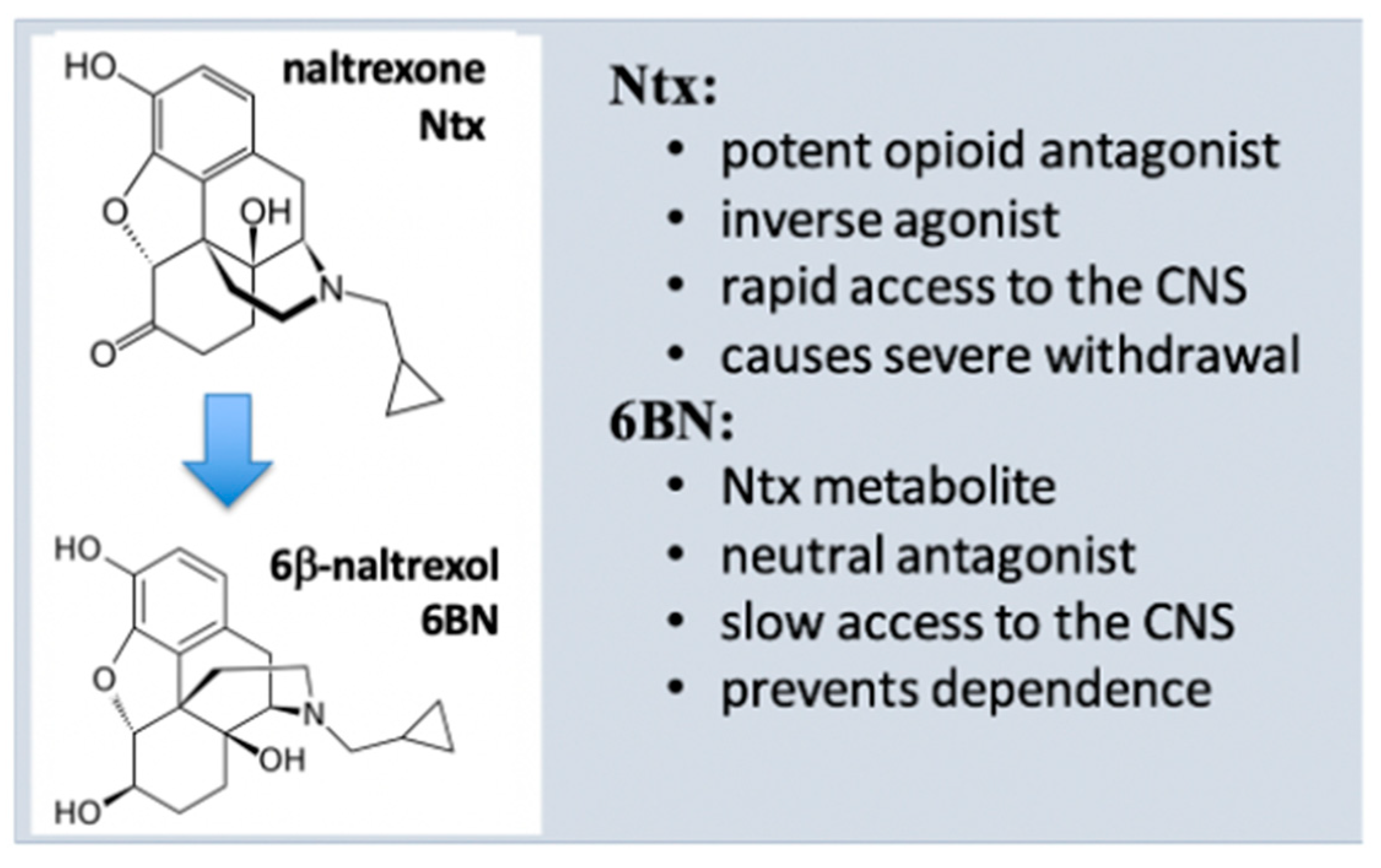

Numerous G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) display ligand-free basal signaling with potential physiological functions, a target in drug development. As an example, the μ opioid receptor (MOR) signals in ligand-free form (MOR-μ*), influencing opioid responses. In addition, agonists bind to MOR but can dissociate upon MOR activation, with ligand-free MOR-μ* carrying out signaling. Opioid pain therapy is effective but incurs adverse effects (ADRs) and risk of opioid use disorder (OUD). Sustained opioid agonist exposure increases persistent basal MOR-μ* activity, which could be a driving force for OUD and ADRs. Antagonists competitively prevent resting MOR (MOR-μ) activation to MOR-μ*, while common antagonists, such as naloxone and naltrexone, also bind to and block ligand-free MOR-μ*, acting as potent inverse agonists. A neutral antagonist, 6β-naltrexol (6BN), binds to but does not block MOR-μ*, preventing MOR-μ activation only competitively with reduced potency.

- C

1. Introduction

2. Physiological Role and Regulation of Basal MOR Signaling

2.1. Regulation and Influence in Pain and Dependence

The ground-state MOR-μ appears to be in an equilibrium with basally active MOR-μ* [20][19]. While the physiological regulation of the MOR-μ–MOR-μ* equilibrium remains enigmatic, β-arrestin-2 and c-Src appear to be involved, down-regulating G protein coupling while also mediating alternative signaling processes [21,22][20][21]. Diverse studies have demonstrated a role of basal MOR signaling in affecting pain perception, for example, counteracting post-surgical pain sensitization [23,24][22][23]. Following repeated opioid dosing, for pain therapy or with illicit use, MOR-μ* displays enhanced and sustained basal activity, involved in analgesia and dependence [25[24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31],26,27,28,29,30,31,32], which can differ between tissue type and brain regions [31][30]. Similarly, increased exposure through enkephalin release during withdrawal was shown to enhance MOR basal signaling, thereby ameliorating withdrawal symptoms [28][27]. In an opioid-dependent state, reversal of MOR-μ* to MOR-μ appears to be slow and MOR-μ* may be a driving force underlying dependence [30][29]. Dependence can last for days and weeks and compulsive drug-seeking behavior much longer, both elements of opioid use disorder (OUD) [33][32].

2.2. Neutral Antagonists and Inverse Agonists

Basal receptor activity can be revealed with the use of neutral antagonists and inverse agonists [36][33]. In vitro and in vivo methods have yielded multiple compounds with a range of effects on basal MOR activity, including diverse neutral MOR antagonists [37,38,39,40][34][35][36][37] and DOR signaling [41,42][38][39]. Naltrexone and naloxone act largely as neutral antagonists at spontaneously signaling MOR-μ* under opioid-naive conditions, whereas both turn into inverse MOR-μ* agonists after morphine pretreatment [34][40]. The same conversion of antagonists into inverse agonists upon agonist exposure has been demonstrated with DOR [43][41]. Studies on biased agonist ligands have shown that MOR exists in multiple conformations that trigger distinct signaling pathways [16,17,18][15][16][17]. One can, thus, hypothesize that the dependent MOR-μ* state differs from MOR-μ* signaling under opioid-naïve conditions, with naloxone changing from a neutral antagonist to an inverse agonist. In a similar fashion, the antipsychotic pimavanserin acts as an inverse agonist at 5HT2A when coupling to Gαi1 but as a neutral antagonist with Gαq/11 [44][42], suggesting that MOR sensitivity could also depend on the signaling pathway. As observed with opioid agonists, treatment with antagonists also affects the MOR-μ–MOR-μ* equilibrium. Generally, treatment with inverse agonists tends to sensitize MOR and enhance the active state (MOR-μ*) while neutral antagonists favor the MOR-μ ground state [45][43].2.3. Ligand-Free Signaling of Opioid Receptors in Peripheral Nociceptors

Basal MOR and DOR signaling in peripheral nociceptors also plays a role in neuropathic pain. Jeske [47][44] summarevieweized the existence of distinct MOR conformations of varying relative abundance as a function of cellular environment and in the periphery compared to the CNS. In peripheral afferent nociceptors, both MOR and DOR maintain a silent status that cannot be readily activated by opioid agonists, possibly because of interactions with GRK2 and β-arrestin [21[20][23][45],24,48], representing, again, a different form of MOR-μ. Inflammatory stimuli lead to activation, both spontaneously to generate basal signaling and restoration of response to agonists for both MOR and DOR. Thus, nociceptive stimuli generate active MOR-μ* as a physiological countermeasure, leading to abatement of neuropathic pain [24,49][23][46]. However, if such basal MOR activity fails to be reversed, or is maintained by opioid drug exposure, it can contribute to chronic neuropathic pain and hyperalgesia, supported by the finding that the peripheral antagonist methylnaltrexone prevents opioid tolerance, dependence, and hyperalgesia [48][45].3. Model of μ Opioid Receptor Signaling

3.1. MOR Activation by Agonists

The model in Figure 1 raises the question of which form of MOR elicits signaling, agonist-bound or ligand-free MOR-μ*, or both. Upon binding, an agonist induces a subtle conformational change that overcomes restraints keeping MOR-μ in its ground state, triggering remodeling of the composite receptor aggregate, subsequently, to engage signaling factors, such as G proteins. Each sequential step can cause conformational changes in the receptor, leading to altered agonist affinity to MOR. Diverse evidence supports the hypothesis that some agonists dissociate rapidly after MOR activation. Proposed in Figure 1, agonists, such as etorphine and morphine, appear to bind MOR-μ with high affinity in rodent brains but rapidly dissociate after activation to ligand-free MOR-μ*, which would then carry out the signaling [20,50][19][47]. Etorphine’s dissociation half-life in vivo is ~50 s, whereas in vitro, it increases to ~40 min (depending on incubation conditions), presumably because the receptor aggregate and coupling to downstream signaling factors are altered.

3.2. Blocking MOR Activation and Signaling by Antagonists

3.3. Differences between the New MOR Model and Classical GPCR Multistate Models

The main classical multistate GPCR model proposes a ternary complex between agonist, receptor, and G protein, representing the active signaling state [58][53], with some modification, including a binary complex of receptor and G protein deemed inactive. The ternary complex undergoes several conformational steps in the activation process, but any effect on agonist affinity was been considered. Inherent to the MOR model in Figure 1 is an initial conformational change triggered by agonist binding that leads to a substantial reorganization of the receptor complex into a persistent active signaling state, during which the agonist loses affinity and dissociates, generating an active binary receptor complex carrying out the signaling. Persistent receptor signaling after dissociation of the agonist has been demonstrated for rhodopsin, suggested to have wider implications for GPCRs [59][54]. Thereby, ligand-free signaling can occur both with spontaneous activation (basal signaling) or upon agonist activation (these signaling complexes may differ in composition). In the classical model of GPCRs with basal ligand-free signaling, inverse agonists are thought to drive the basally active receptor state back to the resting state, whereas neutral antagonists do not [58][53].4. Properties of 6β-Naltrexol (6BN)

4.1. 6BN Pharmacology

As a main metabolite of naltrexone in humans (40–50% of the dose) (Figure 2) [55][51], 6BN has a solid safety record in humans [13][12], is stable, orally bioavailable in mice (~25%) [29][28] and in guinea pigs (~30% [61][55]), and has a half-life of ~12 h in humans [62][56], rendering 6BN highly ‘druggable’. Further, 6BN’s in vitro binding affinity to MOR, DOR, and KOR (κ opioid receptor) is 1.4, 29, and 2 nM, respectively, similar to naltrexone’s affinity profile (0.5, 7, and 1 nM, respectively; all Ki values) [55,63][51][57]. As an inverse MOR agonist, naltrexone blocks opioid analgesia and causes withdrawal in dependent subjects with equally high potency [54,55][50][51] so that it can be administered only 1–2 weeks after complete opioid detoxification. In contrast to naltrexone, 6BN blocks analgesia and elicits withdrawal only at much higher doses than naltrexone [20,55,64][19][51][58]. As a result, 6BN as a metabolite was considered not to contribute to naltrexone’s actions in opioid maintenance therapies [65][59], even though 6BN exceeds naltrexone’s blood levels because of its longer half-life.

4.2. Potent Suppression of Opioid Dependence with Low-Dose 6BN (LD-6BN)

Oberdick et al. [67][60] determined that 6BN given together with morphine to juvenile mice prevents subsequent withdrawal jumping, with an EC50 of ~0.03 mg/kg. This result indicated high potency in a centrally mediated effect, unexpected even when accounting for the immature BBB in mice until day 20 post-partum, allowing rapid access of 6BN to the brain. Safa et al. then showed that 6BN co-administered with methadone potently suppresses withdrawal behavior in adult guinea pigs (IC50 ~ 0.01 mg/kg) [61][55]. Moreover, LD-6BN given s.c. to pregnant guinea pigs together with methadone suppressed withdrawal behavior in the newborn pups, with an ED50 ~ 0.025 mg/kg 6BN [61][55], without deleterious effects and well below the IC50 against methadone antinociception (estimated ~1.0 mg/kg) [61][55].

4.3. Role of 6β-Naltrexol in the Effects of Very-Low-Dose Naltrexone

4.4. Potential Clinical Uses of 6b-Naltrexol

The unique properties of LD-6BN support its clinical potential as an ‘retrograde addiction modulator’ in multiple applications, including safety and utility of opioid analgesics and OUD therapies. Further, 6BN acts in three distinct ways as a function of dose [20,61,66][19][55][64]: 1. modulating elements of addiction at low doses; 2. in addition, selectively blocking peripheral opioid effects at intermediate doses; and 3. antagonizing antinociception at high doses. Moreover, intermediate 6BN doses can be selected such that 6BN accumulation in the body reaches levels that blunt central effects upon high-frequency dosing of opioid agonists with shorter half-lives than 6BN, reducing OUD risk [20][19]. WeIt proposes that 6BN is a candidate drug that can improve opioid pain therapy, reduce OUD risk, facilitate opioid-weaning detoxification, treat neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome [61][55], and improve the safety of opioid maintenance therapies.5. Conclusion

A prominent role of ligand-free MOR-μ* signaling further implies distinct roles for inverse agonists and neutral antagonists. On thermodynamic grounds, ligands can stabilize the MOR receptor conformation towards those with the highest affinity for the ligand, while that process may trigger further remodeling of the receptor aggregate to either initiate signaling or block it (agonists, neutral agonist, and inverse agonist). The proposed novelty of the MOR model in Figure 1 is the hypothesis that a neutral antagonist has the potential to accelerate gradual reversal of MOR-μ* in the dependent state to the resting state—thereby, reversing dependence, captured by the term ‘retrograde addiction modulation’. Reversal of ligand-free signaling of a two-state receptor-signaling complex by a neutral antagonist is opposite to the assumptions made in classical GPCR models [58][53]. Retrograde addiction modulators as clinical agents must also be neutral antagonists to allow opioid analgesia and avoid acute withdrawal. These combined properties could lead to a new class of drugs for OUD and pain therapy, exemplified by 6BN and analogs shown to be neutral MOR antagonists [3[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73][74][75][76][77][78][79][80][81][82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89][90][91][92][93][94][95][96][97][98][99][100][101][102][103][104][105][106][107][108][109][110][111][112][113][114][115][116][117][118][119][120][121][122]4,37,38,39,72,73]. The MOR model proposed in Figure 1 serves as a guide for further study, according to the motto ‘no model is perfect but some are useful’, potentially applicable to many GPCRs.References

- Parnot, C.; Miserey-Lenkei, S.; Bardin, S.; Corvol, P.; Clauser, E. Lessons from constitutively active mutants of G protein-coupled receptors. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 13, 336–343. [CrossRef]Parnot, C.; Miserey-Lenkei, S.; Bardin, S.; Corvol, P.; Clauser, E. Lessons from constitutively active mutants of G protein-coupled receptors. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 13, 336–343.

- Wang, Z. ErbB Receptors and Cancer. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1652, 3–35. [PubMed]Wang, Z. ErbB Receptors and Cancer. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1652, 3–35.

- Aloyo, V.J.; Berg, K.A.; Clarke, W.P.; Spampinato, U.; Harvey, J.A. Inverse agonism at serotonin and cannabinoid receptors. Prog.Aloyo, V.J.; Berg, K.A.; Clarke, W.P.; Spampinato, U.; Harvey, J.A. Inverse agonism at serotonin and cannabinoid receptors. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2010, 91, 1–40.

- Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2010, 91, 1–40.Unal, H.; Karnik, S.S. Domain coupling in GPCRs: The engine for induced conformational changes. Trends Pharm. Sci. 2012, 33, 79–88.

- Unal, H.; Karnik, S.S. Domain coupling in GPCRs: The engine for induced conformational changes. Trends Pharm. Sci. 2012, 33,Pazos, Y.; Casanueva, F.F.; Camiña, J.P. Basic aspects of ghrelin action. Vitam. Horm. 2008, 77, 89–119.

- 79–88. [CrossRef] [PubMed]Solomou, S.; Korbonits, M. The role of ghrelin in weight-regulation disorders: Implications in clinical practice. Hormones 2014, 13, 458–475.

- Molecules 2022, 27, 5826 11 of 13Pimavanserin: Howland, R.H. An Inverse Agonist Antipsychotic Drug. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2016, 54, 21–24.

- Lappano, R.; Maggiolini, M. G protein-coupled receptors: Novel targets for drug discovery in cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2011, 10, 47–60. [CrossRef]Costa, T.; Herz, A. Antagonists with negative intrinsic efficacy at δ opioid receptors coupled to GTP-binding proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 7321–7325.

- Pazos, Y.; Casanueva, F.F.; Camiña, J.P. Basic aspects of ghrelin action. Vitam. Horm. 2008, 77, 89–119. [PubMed]Wang, Z.; Bilsky, E.J.; Porreca, F.; Sadée, W. Constitutive Receptor Activation as a Regulatory Mechanism Underlying Narcotic Tolerance and Dependence. Life Sci. 1994, 54, 339–350.

- Solomou, S.; Korbonits, M. The role of ghrelin in weight-regulation disorders: Implications in clinical practice. Hormones 2014, 13,Salsitz, E.A. Chronic Pain, Chronic Opioid Addiction: A Complex Nexus. J. Med. Toxicol. 2016, 12, 54–57.

- 458–475. [CrossRef]Alter, A.; Yeager, C. The Consequences of COVID-19 on the Overdose Epidemic: Overdoses Are Increasing. Washington/Baltimore High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area. Available online: http://www.odmap.org/Content/docs/news/2020/ODMAP-Report-May2020.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Pimavanserin: Howland, R.H. An Inverse Agonist Antipsychotic Drug. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2016, 54, 21–24.Ayanga, D.; Shorter, D.; Kosten, T.R. Update on pharmacotherapy for treatment of opioid use disorder. Expert Opin. Pharm. 2016, 17, 2307–2318.

- [CrossRef]Valentino, R.J.; Volkow, N.D. Untangling the complexity of opioid receptor function. Neuropsychopharm 2018, 43, 2514–2520.

- Costa, T.; Herz, A. Antagonists with negative intrinsic efficacy at δ opioid receptors coupled to GTP-binding proteins. Proc. Natl.Kandasamy, R.; Hillhouse, T.M.; Livingston, K.E.; Kochan, K.E.; Meurice, C.; Eans, S.O.; Li, M.-H.; White, A.D.; Roques, B.P.; McLaughlin, J.P.; et al. Positive allosteric modulation of the mu-opioid receptor produces analgesia with reduced side effects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2000017118.

- Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 7321–7325. [CrossRef]Schmid, C.L.; Kennedy, N.M.; Ross, N.C.; Lovell, K.M.; Yue, Z.; Morgenweck, J.; Cameron, M.D.; Bannister, T.D.; Bohn, L.M. Bias factor and therapeutic window correlate to predict safer opioid analgesics. Cell 2017, 171, 1165–1175.

- Wang, Z.; Bilsky, E.J.; Porreca, F.; Sadée, W. Constitutive Receptor Activation as a Regulatory Mechanism Underlying NarcoticChakraborty, S.; DiBerto, J.F.; Faouzi, A.; Bernhard, S.M.; Gutridge, A.M.; Ramsey, S.; Zhou, Y.; Provasi, D.; Jilakara, R.; Asher, W.B.; et al. A Novel Mitragynine Analog with Low-Efficacy Mu Opioid Receptor Agonism Displays Antinociception with Attenuated Adverse Effects. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 13873–13892.

- Tolerance and Dependence. Life Sci. 1994, 54, 339–350. [CrossRef]Groer, C.E.; Tidgewell, K.; Moyer, R.A.; Harding, W.W.; Rothman, R.B.; Prisinzano, T.; Bohn, L.M.E. An opioid agonist that does not induce μ-opioid receptor—Arrestin interactions or receptor internalization. Mol. Pharm. 2007, 71, 549–557.

- Salsitz, E.A. Chronic Pain, Chronic Opioid Addiction: A Complex Nexus. J. Med. Toxicol. 2016, 12, 54–57. [CrossRef]Bell, J.; Strang, J. Medication Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder. J. Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 87, 82–88.

- Alter, A.; Yeager, C. The Consequences of COVID-19 on the Overdose Epidemic: Overdoses Are Increasing. Washington/BaltimoreSadee, W.; Oberdick, J.; Wang, Z. Biased opioid antagonists as modulators of opioid dependence: Opportunities to improve pain therapy and opioid use management. Molecules 2020, 25, 4163.

- High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area. Available online: http://www.odmap.org/Content/docs/news/2020/ODMAP-Report-Walwyn, W.; Evans, C.J.; Hales, T.G. Beta-arrestin2 and c-Src regulate the constitutive activity and recycling of mu opioid receptors in dorsal root ganglion neurons. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 5092–5104.

- May2020.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2020).Lam, H.; Maga, M.; Pradhan, A.; Evans, C.J.; Maidment, N.T.; Hales, T.G.; Walwyn, W. Analgesic tone conferred by constitutively active mu opioid receptors in mice lacking β-arrestin. Mol. Pain. 2011, 7, 24.

- Ayanga, D.; Shorter, D.; Kosten, T.R. Update on pharmacotherapy for treatment of opioid use disorder. Expert Opin. Pharm. 2016,Cooper, A.H.; Hedden, N.S.; Prasoon, P.; Qi, Y.; Taylor, B.K. Post-surgical latent pain sensitization is driven by descending serotonergic facilitation and masked by µ-opioid receptor constitutive activity (MORCA) in the rostral ventromedial medulla. J. Neurosci. 2022, 42, 5811–5870.

- 17, 2307–2318. [CrossRef] [PubMed]Sullivan, L.C.; Chavera, T.S.; Jamshidi, R.J.; Berg, K.A.; Clarke, W.P. Constitutive Desensitization of Opioid Receptors in Peripheral Sensory Neurons. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2016, 359, 411–419.

- Valentino, R.J.; Volkow, N.D. Untangling the complexity of opioid receptor function. Neuropsychopharm 2018, 43, 2514–2520.Navani, D.M.; Sirohi, S.; Madia, P.A.; Yoburn, B.C. The role of opioid antagonist efficacy and constitutive opioid receptor activity in the opioid withdrawal syndrome in mice. Pharm. Biochem. Behav. 2011, 99, 671–675.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed]Shoblock, J.R.; Maidment, N.T. Constitutively active opioid receptors mediate the enhanced conditioned aversive effect of naloxone in morphine-dependent mice. Neuropsychopharm 2006, 31, 171–177.

- Kandasamy, R.; Hillhouse, T.M.; Livingston, K.E.; Kochan, K.E.; Meurice, C.; Eans, S.O.; Li, M.-H.; White, A.D.; Roques, B.P.;Liu, J.G.; Prather, P.L. Chronic exposure to mu-opioid agonists produces constitutive activation of mu-opioid receptors in direct proportion to the efficacy of the agonist used for pretreatment. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001, 60, 53–62.

- McLaughlin, J.P.; et al. Positive allosteric modulation of the mu-opioid receptor produces analgesia with reduced side effects.Shoblock, J.R.; Maidment, N.T. Enkephalin release promotes homeostatic increases in constitutively active mu opioid receptors during morphine withdrawal. Neuroscience 2007, 149, 642–649.

- Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2000017118. [CrossRef] [PubMed]Raehal, K.M.; Lowery, J.J.; Bhamidipati, C.M.; Paolino, R.M.; Blair, J.R.; Wang, D.; Sadée, W.; Bilsky, E.J. In vivo characterization of 6β-naltrexol, an opioid ligand with less inverse agonist activity compared with naltrexone and naloxone in opioid-dependent mice. J Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005, 313, 1150–1162.

- Schmid, C.L.; Kennedy, N.M.; Ross, N.C.; Lovell, K.M.; Yue, Z.; Morgenweck, J.; Cameron, M.D.; Bannister, T.D.; Bohn, L.M. BiasSadee, W.; Wang, D.; Bilsky, E.J. Basal opioid receptor activity, neutral antagonists, and therapeutic opportunities. Life Sci. 2005, 76, 1427–1437.

- factor and therapeutic window correlate to predict safer opioid analgesics. Cell 2017, 171, 1165–1175. [CrossRef]Wang, D.; Raehal, K.M.; Lin, E.T.; Lowery, J.J.; Kieffer, B.L.; Bilsky, E.J.; Sadée, W. Basal signaling opioid receptor in mouse brain: Role in narcotic dependence. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004, 308, 512–520.

- Chakraborty, S.; DiBerto, J.F.; Faouzi, A.; Bernhard, S.M.; Gutridge, A.M.; Ramsey, S.; Zhou, Y.; Provasi, D.; Jilakara, R.; Asher, W.B.; et al. A Novel Mitragynine Analog with Low-Efficacy Mu Opioid Receptor Agonism Displays Antinociception withCorder, G.; Doolen, S.; Donahue, R.R.; Winter, M.K.; Jutras, B.K.L.; He, Y.; Hu, X.; Wieskopf, J.S.; Mogil, J.S.; Storm, D.R.; et al. Constitutive μ-opioid receptor activity leads to long-term endogenous analgesia and dependence. Science 2013, 341, 1394–1399.

- Attenuated Adverse Effects. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 13873–13892. [CrossRef]Blanco, C.; Wall, M.M.; Olfson, M. Expanding Current Approaches to Solve the Opioid Crisis. JAMA Psychiatry 2022, 79, 5–6.

- Groer, C.E.; Tidgewell, K.; Moyer, R.A.; Harding, W.W.; Rothman, R.B.; Prisinzano, T.; Bohn, L.M.E. An opioid agonist that doesBilsky, E.J.; Giuvelis, D.; Osborn, M.D.; Dersch, C.M.; Xu, H.; Rothman, R.B. In vitro and in vivo assessment of m opioid receptor constitutive activity. Methods Enzymol. 2010, 484, 413–443.

- not induce μ-opioid receptor—Arrestin interactions or receptor internalization. Mol. Pharm. 2007, 71, 549–557. [CrossRef]Sally, E.J.; Xu, H.; Dersch, C.M.; Hsin, L.W.; Chang, L.T.; Prisinzano, T.E.; Simpson, D.S.; Giuvelis, D.; Rice, K.C.; Jacobson, A.E.; et al. Identification of a novel “almost neutral” micro-opioid receptor antagonist in CHO cells expressing the cloned human mu-opioid receptor. Synapse 2010, 64, 280–288.

- Bell, J.; Strang, J. Medication Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder. J. Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 87, 82–88. [CrossRef]Marczak, E.D.; Jinsmaa, Y.; Li, T.; Bryant, S.D.; Tsuda, Y.; Okada, Y.; Lazarus, L.H. -endomorphins are μ-opioid receptor antagonists lacking inverse agonist properties. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2007, 323, 374–380.

- Sadee, W.; Oberdick, J.; Wang, Z. Biased opioid antagonists as modulators of opioid dependence: Opportunities to improve painTsuruda, P.R.; Vickery, R.G.; Long, D.D.; Armstrong, S.R.; Beattie, D.T. The in vitro pharmacological profile of TD-1211, a neutral opioid receptor antagonist. Naunyn. Schmied. Arch. Pharm. 2013, 386, 479–491.

- therapy and opioid use management. Molecules 2020, 25, 4163. [CrossRef]Dutta, R.; Lunzer, M.M.; Auger, J.L.; Akgün, E.; Portoghese, P.S.; Binstadt, B.A. A bivalent compound targeting CCR5 and the mu opioid receptor treats inflammatory arthritis pain in mice without inducing pharmacologic tolerance. Arthritis. Res. Ther. 2018, 20, 154.

- Walwyn, W.; Evans, C.J.; Hales, T.G. Beta-arrestin2 and c-Src regulate the constitutive activity and recycling of mu opioid receptorsHirayama, S.; Fujii, H. δ Opioid Receptor Inverse Agonists and Their In Vivo Pharmacological Effects. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2020, 20, 2889–2902.

- in dorsal root ganglion neurons. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 5092–5104. [CrossRef]Iwamatsu, C.; Hayakawa, D.; Kono, T.; Honjo, A.; Ishizaki, S.; Hirayama, S.; Gouda, H.; Fujii, H. Effects of N-Substituents on the Functional Activities of Naltrindole Derivatives for the δ Opioid Receptor: Synthesis and Evaluation of Sulfonamide Derivatives. Molecules 2020, 25, 3792.

- Lam, H.; Maga, M.; Pradhan, A.; Evans, C.J.; Maidment, N.T.; Hales, T.G.; Walwyn, W. Analgesic tone conferred by constitutivelyWang, D.; Raehal, K.M.; Bilsky, E.J.; Sadée, W. Inverse agonists and neutral antagonists at μ opioid receptor (MOR): Possible role of basal receptor signaling in narcotic dependence. J. Neurochem. 2001, 77, 1590–1600.

- active mu opioid receptors in mice lacking β-arrestin. Mol. Pain. 2011, 7, 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]Liu, J.G.; Prather, P.L. Chronic agonist treatment converts antagonists into inverse agonists at delta-opioid receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002, 302, 1070–1079.

- Cooper, A.H.; Hedden, N.S.; Prasoon, P.; Qi, Y.; Taylor, B.K. Post-surgical latent pain sensitization is driven by descending serotonergic facilitation and masked by μ-opioid receptor constitutive activity (MORCA) in the rostral ventromedial medulla. J.Muneta-Arrate, I.; Diez-Alarcia, R.; Horrillo, I.; Meana, J.J. Pimavanserin exhibits serotonin 5-HT2A receptor inverse agonism for Gαi1- and neutral antagonism for Gαq/11-proteins in human brain cortex. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020, 36, 83–89.

- Neurosci. 2022, 42, 5811–5870. [CrossRef]Morris, B.J.; Millan, M.J. Inability of an opioid antagonist lacking negative intrinsic activity to induce opioid receptor up-regulation in vivo. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1991, 102, 883–886.

- Sullivan, L.C.; Chavera, T.S.; Jamshidi, R.J.; Berg, K.A.; Clarke, W.P. Constitutive Desensitization of Opioid Receptors in PeripheralJeske, N.A. Dynamic Opioid Receptor Regulation in the Periphery. Mol. Pharmacol. 2019, 95, 463–467.

- Sensory Neurons. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2016, 359, 411–419. [CrossRef] [PubMed]Corder, G.; Tawfik, V.L.; Wang, D.; Sypek, E.I.; Low, S.A.; Dickinson, J.R.; Sotoudeh, C.; Clark, J.D.; Barres, B.A.; Bohlen, C.J.; et al. Loss of mu opioid receptor signaling in nociceptors, but not microglia, abrogates morphine tolerance without disrupting analgesia. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 164–173.

- Navani, D.M.; Sirohi, S.; Madia, P.A.; Yoburn, B.C. The role of opioid antagonist efficacy and constitutive opioid receptor activityWalwyn, W.M.; Chen, C.; Kim, H.; Minasyan, A.; Ennes, H.S.; McRoberts, J.A.; Marvizon, J.C.G. Sustained suppression of hyperalgesia during latent sensitization by mu-, delta-, and kappa-opioid receptors and 2A-adrenergic receptors: Role of constitutive activity. Neurobiol. Dis. 2016, 36, 204–221.

- in the opioid withdrawal syndrome in mice. Pharm. Biochem. Behav. 2011, 99, 671–675. [CrossRef] [PubMed]Perry, D.C.; Rosenbaum, J.S.; Kurowski, M.; Sadée, W. 3H-Etorphine Receptor Binding In Vivo: Small Fractional Occupancy Elicits Analgesia. Mol. Pharmacol. 1982, 21, 272–279.

- Shoblock, J.R.; Maidment, N.T. Constitutively active opioid receptors mediate the enhanced conditioned aversive effect ofMonroe Butler, P.M.; Barash, J.A.; Casaletto, K.B.; Cotter, D.L.; La Joie, R.; Geschwind, M.D.; Rosen, H.J.; Kramer, J.H.; Miller, B.L. An Opioid-Related Amnestic Syndrome with Persistent Effects on Hippocampal Structure and Function. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 31, 392–396.

- naloxone in morphine-dependent mice. Neuropsychopharm 2006, 31, 171–177. [CrossRef] [PubMed]Sirohi, S.; Dighe, S.V.; Madia, P.A.; Yoburn, B.C. The relative potency of inverse opioid agonists and a neutral opioid antagonist in precipitated withdrawal and antagonism of analgesia and toxicity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009, 330, 513–519.

- Liu, J.G.; Prather, P.L. Chronic exposure to mu-opioid agonists produces constitutive activation of mu-opioid receptors in directLi, J.-X.; Mc Mahon, L.R.; France, C.P. Comparison of naltrexone, 6α-naltrexol, and 6β-naltrexol in morphine-dependent and in non-dependent rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology 2007, 195, 479–486.

- proportion to the efficacy of the agonist used for pretreatment. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001, 60, 53–62. [CrossRef] [PubMed]Porter, S.J.; Somogyi, A.A.; White, J.M. In vivo and in vitro potency studies of 6β-naltrexol, the major human metabolite of naltrexone. Addict. Biol. 2002, 7, 219–225.

- Shoblock, J.R.; Maidment, N.T. Enkephalin release promotes homeostatic increases in constitutively active mu opioid receptorsRosenbaum, J.S.; Holford, N.H.G.; Richard, M.L.; Aman, R.A.; Sadee, W. Discrimination of three types of opioid binding sites in rat brain in vivo. Mol. Pharmacol. 1984, 25, 242–248.

- during morphine withdrawal. Neuroscience 2007, 149, 642–649. [CrossRef]Perez, D.M.; Karnik, S.S. Multiple signaling states of G-protein-coupled receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2005, 57, 147–161.

- Raehal, K.M.; Lowery, J.J.; Bhamidipati, C.M.; Paolino, R.M.; Blair, J.R.; Wang, D.; Sadée, W.; Bilsky, E.J. In vivo characterization ofSchafer, C.T.; Fay, J.F.; Janz, J.M.; Farrens, D.L. Decay of an active GPCR: Conformational dynamics govern agonist rebinding and persistence of an active, yet empty, receptor state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 11961–11966.

- 6β-naltrexol, an opioid ligand with less inverse agonist activity compared with naltrexone and naloxone in opioid-dependentSafa, A.; Lau, A.R.; Aten, S.; Schilling, K.; Bales, K.L.; Miller, V.; Fitzgerald, J.; Chen, M.; Hill, K.; Dzwigalski, K.; et al. Pharmacological prevention of neonatal opioid withdrawal in a pregnant guinea pig model. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 613328.

- mice. J Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005, 313, 1150–1162. [CrossRef]Yancey-Wrona, J.; Dallaire, B.; Bilsky, E.J.; Bath, B.; Burkart, J.; Wenster, L.; Magiera, D.; Yang, X.; Phelps, M.A.; Sadee, W. 6β-Naltrexol, a peripherally selective opioid antagonist that inhibits morphine-induced slowing of gastrointestinal transit: An exploratory study. Pain Med. 2011, 12, 1727–1737.

- Sadee, W.; Wang, D.; Bilsky, E.J. Basal opioid receptor activity, neutral antagonists, and therapeutic opportunities. Life Sci. 2005,Wang, D.; Sun, X.; Sadee, W. 2007 Different effects of opioid antagonists on mu, delta, and kappa opioid receptors with and without agonist pretreatment. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2011, 321, 544–552.

- 76, 1427–1437. [CrossRef]Divin, M.F.; Holden Ko, M.C.; Traynor, J.R. Comparison of the opioid receptor antagonist properties of naltrexone and 6beta-naltrexol in morphine-naïve and morphine-dependent mice. Eur. J. Pharmocol. 2008, 583, 48–55.

- Wang, D.; Raehal, K.M.; Lin, E.T.; Lowery, J.J.; Kieffer, B.L.; Bilsky, E.J.; Sadée, W. Basal signaling opioid receptor in mouse brain:Fujimoto, J.M.; Roerig, S.; Wang, R.I.; Chatterjie, N.; Inturrisi, C.E. Narcotic antagonist activity of several metabolites of naloxone and naltrexone tested in morphine dependent mice (38558). Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1975, 148, 443–448.

- Role in narcotic dependence. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004, 308, 512–520. [CrossRef] [PubMed]Oberdick, J.; Ling, Y.; Phelps, M.A.; Yudovich, M.S.; Schilling, K.; Sadee, W. Preferential delivery of an opioid antagonist to the fetal brain in pregnant mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2016, 358, 22–30.

- Corder, G.; Doolen, S.; Donahue, R.R.; Winter, M.K.; Jutras, B.K.L.; He, Y.; Hu, X.; Wieskopf, J.S.; Mogil, J.S.; Storm, D.R.; et al.Toljan, K.; Vrooman, B. Low-Dose Naltrexone (LDN)-Review of Therapeutic Utilization. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 82.

- Constitutive μ-opioid receptor activity leads to long-term endogenous analgesia and dependence. Science 2013, 341, 1394–1399. [CrossRef] [PubMed]Leri, F.; Burns, L.H. Ultra-low-dose naltrexone reduces the rewarding potency of oxycodone and relapse vulnerability in rats. Pharm. Biochem. Behav. 2018, 82, 252–262.

- Molecules 2022, 27, 5826 12 of 13Mannelli, P.; Patkar, A.A.; Peindl, K.; Gorelick, D.A.; Wu, L.-T.; Gottheil, E. Very low dose naltrexone addition in opioid detoxification: A randomized, controlled trial. Addict. Biol. 2009, 14, 204–213.

- Blanco, C.; Wall, M.M.; Olfson, M. Expanding Current Approaches to Solve the Opioid Crisis. JAMA Psychiatry 2022, 79, 5–6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]Yancey-Wrona, J.E.; Raymond, T.J.; Mercer, H.K.; Sadee, W.; Bilsky, E.J. 6β-Naltrexol preferentially antagonizes opioid effects on gastrointestinal transit compared to antinociception in mice. Life Sci. 2009, 85, 413–420.

- Wang, D.; Raehal, K.M.; Bilsky, E.J.; Sadée, W. Inverse agonists and neutral antagonists at μ opioid receptor (MOR): Possible role of basal receptor signaling in narcotic dependence. J. Neurochem. 2001, 77, 1590–1600. [CrossRef] [PubMed]Comer, S.D.; Mannelli, P.; Alam, D.; Douaihy, A.; Nangia, N.; Akerman, S.C.; Zavod, A.; Silverman, B.L.; Sullivan, M.A. Transition of Patients with Opioid Use Disorder from Buprenorphine to Extended Release Naltrexone: A Randomized Clinical Trial Assessing Two Transition Regimens. Am. J. Addict. 2020, 29, 313–322.

- Sirohi, S.; Dighe, S.V.; Madia, P.A.; Yoburn, B.C. The relative potency of inverse opioid agonists and a neutral opioid antagonist in precipitated withdrawal and antagonism of analgesia and toxicity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009, 330, 513–519. [CrossRef]Bartlett, J.L.; Lavoie, N.R.; Raehal, K.M.; Sadee, W.; Bilsky, E.J. In vivo studies with 6β-naltrexamide, a peripherally selective opioid antagonist that has less inverse agonist activity than naltrexone and naloxone. FASEB J. 2004, 18, A586.

- Bilsky, E.J.; Giuvelis, D.; Osborn, M.D.; Dersch, C.M.; Xu, H.; Rothman, R.B. In vitro and in vivo assessment of m opioid receptor constitutive activity. Methods Enzymol. 2010, 484, 413–443.

- Sally, E.J.; Xu, H.; Dersch, C.M.; Hsin, L.W.; Chang, L.T.; Prisinzano, T.E.; Simpson, D.S.; Giuvelis, D.; Rice, K.C.; Jacobson, A.E.; et al. Identification of a novel “almost neutral” micro-opioid receptor antagonist in CHO cells expressing the cloned human mu-opioid receptor. Synapse 2010, 64, 280–288. [CrossRef]

- Marczak, E.D.; Jinsmaa, Y.; Li, T.; Bryant, S.D.; Tsuda, Y.; Okada, Y.; Lazarus, L.H. [N-allyl-Dmt1]-endomorphins are μ-opioid receptor antagonists lacking inverse agonist properties. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2007, 323, 374–380. [CrossRef]

- Tsuruda, P.R.; Vickery, R.G.; Long, D.D.; Armstrong, S.R.; Beattie, D.T. The in vitro pharmacological profile of TD-1211, a neutral opioid receptor antagonist. Naunyn. Schmied. Arch. Pharm. 2013, 386, 479–491. [CrossRef]

- Dutta, R.; Lunzer, M.M.; Auger, J.L.; Akgün, E.; Portoghese, P.S.; Binstadt, B.A. A bivalent compound targeting CCR5 and the mu opioid receptor treats inflammatory arthritis pain in mice without inducing pharmacologic tolerance. Arthritis. Res. Ther. 2018, 20, 154. [CrossRef]

- Hirayama, S.; Fujii, H. δ Opioid Receptor Inverse Agonists and Their In Vivo Pharmacological Effects. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2020, 20, 2889–2902. [CrossRef]

- Iwamatsu, C.; Hayakawa, D.; Kono, T.; Honjo, A.; Ishizaki, S.; Hirayama, S.; Gouda, H.; Fujii, H. Effects of N-Substituents on the Functional Activities of Naltrindole Derivatives for the δ Opioid Receptor: Synthesis and Evaluation of Sulfonamide Derivatives. Molecules 2020, 25, 3792. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.G.; Prather, P.L. Chronic agonist treatment converts antagonists into inverse agonists at delta-opioid receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002, 302, 1070–1079. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muneta-Arrate, I.; Diez-Alarcia, R.; Horrillo, I.; Meana, J.J. Pimavanserin exhibits serotonin 5-HT2A receptor inverse agonism for Gαi1- and neutral antagonism for Gαq/11-proteins in human brain cortex. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020, 36, 83–89. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, B.J.; Millan, M.J. Inability of an opioid antagonist lacking negative intrinsic activity to induce opioid receptor up-regulation in vivo. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1991, 102, 883–886. [CrossRef]

- Piñeyro, G.; Azzi, M.; deLean, A.; Schiller, P.W.; Bouvier, M. Reciprocal regulation of agonist and inverse agonist signaling efficacy upon short-term treatment of the human delta-opioid receptor with an inverse agonist. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005, 67, 336–348. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeske, N.A. Dynamic Opioid Receptor Regulation in the Periphery. Mol. Pharmacol. 2019, 95, 463–467. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corder, G.; Tawfik, V.L.; Wang, D.; Sypek, E.I.; Low, S.A.; Dickinson, J.R.; Sotoudeh, C.; Clark, J.D.; Barres, B.A.; Bohlen, C.J.; et al. Loss of mu opioid receptor signaling in nociceptors, but not microglia, abrogates morphine tolerance without disrupting

- analgesia. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 164–173. [CrossRef]

- Walwyn, W.M.; Chen, C.; Kim, H.; Minasyan, A.; Ennes, H.S.; McRoberts, J.A.; Marvizon, J.C.G. Sustained suppression of

- hyperalgesia during latent sensitization by mu-, delta-, and kappa-opioid receptors and 2A-adrenergic receptors: Role of

- constitutive activity. Neurobiol. Dis. 2016, 36, 204–221.

- Perry, D.C.; Rosenbaum, J.S.; Kurowski, M.; Sadée, W. 3H-Etorphine Receptor Binding In Vivo: Small Fractional Occupancy

- Elicits Analgesia. Mol. Pharmacol. 1982, 21, 272–279.

- Rosenbaum, J.S.; Holford, N.H.G.; Sadée, W. In Vivo Receptor Binding of Opioid Drugs at the μ Site. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1985,

- 233, 735–740.

- Monroe Butler, P.M.; Barash, J.A.; Casaletto, K.B.; Cotter, D.L.; La Joie, R.; Geschwind, M.D.; Rosen, H.J.; Kramer, J.H.; Miller, B.L.

- An Opioid-Related Amnestic Syndrome with Persistent Effects on Hippocampal Structure and Function. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin.

- Neurosci. 2019, 31, 392–396. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, J.D.; Gordon, N.C.; Bornstein, J.C.; Fields, H.L. Analgesic responses to morphine and placebo in individuals with

- postoperative pain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1981, 10, 379–389. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-X.; Mc Mahon, L.R.; France, C.P. Comparison of naltrexone, 6α-naltrexol, and 6β-naltrexol in morphine-dependent and in

- non-dependent rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology 2007, 195, 479–486. [CrossRef]

- Porter, S.J.; Somogyi, A.A.; White, J.M. In vivo and in vitro potency studies of 6β-naltrexol, the major human metabolite of

- naltrexone. Addict. Biol. 2002, 7, 219–225. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbaum, J.S.; Holford, N.H.G.; Richard, M.L.; Aman, R.A.; Sadee, W. Discrimination of three types of opioid binding sites in

- rat brain in vivo. Mol. Pharmacol. 1984, 25, 242–248. [PubMed]

- Ko, M.C.; Divin, M.F.; Lee, H.; Woods, J.H.; Traynor, J.R. Differential in Vivo Potencies of Naltrexone and 6β-Naltrexol in the

- Monkey. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006, 316, 772–779. [CrossRef]

- Perez, D.M.; Karnik, S.S. Multiple signaling states of G-protein-coupled receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2005, 57, 147–161. [CrossRef]

- Molecules 2022, 27, 5826 13 of 13

- Schafer, C.T.; Fay, J.F.; Janz, J.M.; Farrens, D.L. Decay of an active GPCR: Conformational dynamics govern agonist rebinding and persistence of an active, yet empty, receptor state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 11961–11966. [CrossRef]

- Piñeyro, G.; Azzi, M.; deLéan, A.; Schiller, P.A.; Bouvier, M. Short-term inverse agonist treatment induces reciprocal changes in delta-opioid agonist and inverse agonist binding capacity. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001, 67, 816–827.

- Safa, A.; Lau, A.R.; Aten, S.; Schilling, K.; Bales, K.L.; Miller, V.; Fitzgerald, J.; Chen, M.; Hill, K.; Dzwigalski, K.; et al. Pharmacological prevention of neonatal opioid withdrawal in a pregnant guinea pig model. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 613328. [CrossRef]

- Yancey-Wrona, J.; Dallaire, B.; Bilsky, E.J.; Bath, B.; Burkart, J.; Wenster, L.; Magiera, D.; Yang, X.; Phelps, M.A.; Sadee, W. 6β-Naltrexol, a peripherally selective opioid antagonist that inhibits morphine-induced slowing of gastrointestinal transit: An exploratory study. Pain Med. 2011, 12, 1727–1737. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Sun, X.; Sadee, W. 2007 Different effects of opioid antagonists on mu, delta, and kappa opioid receptors with and without agonist pretreatment. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2011, 321, 544–552. [CrossRef]

- Divin, M.F.; Holden Ko, M.C.; Traynor, J.R. Comparison of the opioid receptor antagonist properties of naltrexone and 6beta- naltrexol in morphine-naïve and morphine-dependent mice. Eur. J. Pharmocol. 2008, 583, 48–55. [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, J.M.; Roerig, S.; Wang, R.I.; Chatterjie, N.; Inturrisi, C.E. Narcotic antagonist activity of several metabolites of naloxone and naltrexone tested in morphine dependent mice (38558). Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1975, 148, 443–448. [CrossRef]

- Yancey-Wrona, J.E.; Raymond, T.J.; Mercer, H.K.; Sadee, W.; Bilsky, E.J. 6β-Naltrexol preferentially antagonizes opioid effects on gastrointestinal transit compared to antinociception in mice. Life Sci. 2009, 85, 413–420. [CrossRef]

- Oberdick, J.; Ling, Y.; Phelps, M.A.; Yudovich, M.S.; Schilling, K.; Sadee, W. Preferential delivery of an opioid antagonist to the fetal brain in pregnant mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2016, 358, 22–30. [CrossRef]

- Perry, D.C.; Mullis, K.B.; Oie, S.; Sadée, W. Opiate Antagonist Receptor Binding In Vivo: Evidence for a New Receptor Binding Model. Brain Res. 1980, 199, 49–61. [CrossRef]

- Toljan, K.; Vrooman, B. Low-Dose Naltrexone (LDN)-Review of Therapeutic Utilization. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 82. [CrossRef]

- Leri, F.; Burns, L.H. Ultra-low-dose naltrexone reduces the rewarding potency of oxycodone and relapse vulnerability in rats.

- Pharm. Biochem. Behav. 2018, 82, 252–262. [CrossRef]

- Mannelli, P.; Patkar, A.A.; Peindl, K.; Gorelick, D.A.; Wu, L.-T.; Gottheil, E. Very low dose naltrexone addition in opioid

- detoxification: A randomized, controlled trial. Addict. Biol. 2009, 14, 204–213. [CrossRef]

- Comer, S.D.; Mannelli, P.; Alam, D.; Douaihy, A.; Nangia, N.; Akerman, S.C.; Zavod, A.; Silverman, B.L.; Sullivan, M.A. Transition

- of Patients with Opioid Use Disorder from Buprenorphine to Extended Release Naltrexone: A Randomized Clinical Trial

- Assessing Two Transition Regimens. Am. J. Addict. 2020, 29, 313–322. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, J.L.; Lavoie, N.R.; Raehal, K.M.; Sadee, W.; Bilsky, E.J. In vivo studies with 6β-naltrexamide, a peripherally selective

- opioid antagonist that has less inverse agonist activity than naltrexone and naloxone. FASEB J. 2004, 18, A586.