In the context of chemistry and molecular modelling, a force field is a computational method that is used to estimate the forces between atoms within molecules and also between molecules. More precisely, the force field refers to the functional form and parameter sets used to calculate the potential energy of a system of atoms or coarse-grained particles in molecular mechanics, molecular dynamics, or Monte Carlo simulations. The parameters for a chosen energy function may be derived from experiments in physics and chemistry, calculations in quantum mechanics, or both. Force fields are interatomic potentials and utilize the same concept as force fields in classical physics, with the difference that the force field parameters in chemistry describe the energy landscape, from which the acting forces on every particle are derived as a gradient of the potential energy with respect to the particle coordinates. All-atom force fields provide parameters for every type of atom in a system, including hydrogen, while united-atom interatomic potentials treat the hydrogen and carbon atoms in methyl groups and methylene bridges as one interaction center. Coarse-grained potentials, which are often used in long-time simulations of macromolecules such as proteins, nucleic acids, and multi-component complexes, sacrifice chemical details for higher computing efficiency.

- macromolecules

- force field parameters

- multi-component

1. Functional Form

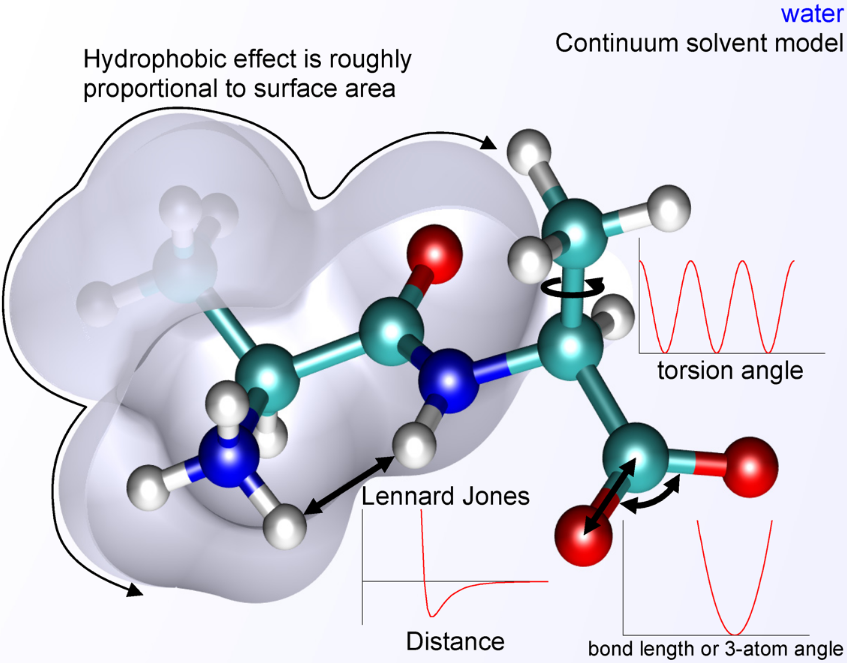

The basic functional form of potential energy in molecular mechanics includes bonded terms for interactions of atoms that are linked by covalent bonds, and nonbonded (also termed noncovalent) terms that describe the long-range electrostatic and van der Waals forces. The specific decomposition of the terms depends on the force field, but a general form for the total energy in an additive force field can be written as [math]\displaystyle{ E_{\text{total}} = E_{\text{bonded}} + E_{\text{nonbonded}} }[/math] where the components of the covalent and noncovalent contributions are given by the following summations: [math]\displaystyle{ E_{\text{bonded}} = E_{\text{bond}} + E_{\text{angle}} + E_{\text{dihedral}} }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ E_{\text{nonbonded}} = E_{\text{electrostatic}} + E_{\text{van der Waals}} }[/math]

The bond and angle terms are usually modeled by quadratic energy functions that do not allow bond breaking. A more realistic description of a covalent bond at higher stretching is provided by the more expensive Morse potential. The functional form for dihedral energy is variable from one force field to another. Additional, "improper torsional" terms may be added to enforce the planarity of aromatic rings and other conjugated systems, and "cross-terms" that describe the coupling of different internal variables, such as angles and bond lengths. Some force fields also include explicit terms for hydrogen bonds.

The nonbonded terms are computationally most intensive. A popular choice is to limit interactions to pairwise energies. The van der Waals term is usually computed with a Lennard-Jones potential and the electrostatic term with Coulomb's law. However, both can be buffered or scaled by a constant factor to account for electronic polarizability. Studies with this energy expression have focused on biomolecules since the 1970s and were generalized to compounds across the periodic table in the early 2000s, including metals, ceramics, minerals, and organic compounds.[1]

1.1. Bond Stretching

As it is rare for bonds to deviate significantly from their reference values, the most simplistic approaches utilize a Hooke's law formula: [math]\displaystyle{ E_{\text{bond}} = \frac{k_{ij}}{2} (l_{ij}-l_{0,ij})^2 }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ k_{ij} }[/math] is the force constant, [math]\displaystyle{ l_{ij} }[/math] is the bond length and [math]\displaystyle{ l_{0,ij} }[/math] is the value for the bond length between atoms [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math] when all other terms in the force field are set to 0. The term [math]\displaystyle{ l_{0,ij} }[/math] is often referred to as the equilibrium bond length, which may cause confusion. The equilibrium bond length is the value adopted in equilibrium at 298 K with all other force field terms and kinetic energy contributing. Therefore, [math]\displaystyle{ l_{0,ij} }[/math] is often a few percent different from the actual bond length in experiments at 298 K.[1]

The bond stretching constant [math]\displaystyle{ k_{ij} }[/math] can be determined from the experimental Infrared spectrum, Raman spectrum, or high-level quantum mechanical calculations. The constant [math]\displaystyle{ k_{ij} }[/math] determines vibrational frequencies in molecular dynamics simulations. The stronger the bond is between atoms, the higher is the value of the force constant, and the higher the wavenumber (energy) in the IR/Raman spectrum. The vibration spectrum according to a given force constant can be computed from short MD trajectories (5 ps) with ~1 fs time steps, calculation of the velocity autocorrelation function, and its Fourier transform.[2]

Though the formula of Hooke's law provides a reasonable level of accuracy at bond lengths near the equilibrium distance, it is less accurate as one moves away. In order to model the Morse curve better one could employ cubic and higher powers.[3][4] However, for most practical applications these differences are negligible and inaccuracies in predictions of bond lengths are on the order of the thousandth of an angstrom, which is also the limit of reliability for common force fields. A Morse potential can be employed instead to enable bond breaking and higher accuracy, even though it is less efficient to compute.

1.2. Electrostatic Interactions

Electrostatic interactions are represented by a Coulomb energy, which utilizes atomic charges [math]\displaystyle{ q_i }[/math] to represent chemical bonding ranging from covalent to polar covalent and ionic bonding. The typical formula is the Coulomb law: [math]\displaystyle{ E_{\text{Coulomb}} = \frac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon_0}\frac{q_i q_j}{r_{ij}} }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ r_{ij} }[/math] is the distance between two atoms [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math]. The total Coulomb energy is a summation over all pairwise combinations of atoms and usually excludes 1, 2 bonded atoms, 1, 3 bonded atoms, as well as 1, 4 bonded atoms.[5][6][7]

Atomic charges can make dominant contributions to the potential energy, especially for polar molecules and ionic compounds, and are critical to simulate the geometry, interaction energy, as well as the reactivity. The assignment of atomic charges often still follows empirical and unreliable quantum mechanical protocols, which often lead to several 100% uncertainty relative to physically justified values in agreement with experimental dipole moments and theory.[8][9][10] Reproducible atomic charges for force fields based on experimental data for electron deformation densities, internal dipole moments, and an Extended Born model have been developed.[1][10] Uncertainties <10%, or ±0.1e, enable a consistent representation of chemical bonding and up to hundred times higher accuracy in computed structures and energies along with physical interpretation of other parameters in the force field.

2. Parameterization

In addition to the functional form of the potentials, force fields define a set of parameters for different types of atoms, chemical bonds, dihedral angles, out-of-plane interactions, nonbond interactions, and possible other terms.[1] Many parameter sets are empirical and some force fields use extensive fitting terms that are difficult to assign a physical interpretation.[11] Atom types are defined for different elements as well as for the same elements in sufficiently different chemical environments. For example, oxygen atoms in water and an oxygen atoms in a carbonyl functional group are classified as different force field types.[12] Typical force field parameter sets include values for atomic mass, atomic charge, Lennard-Jones parameters for every atom type, as well as equilibrium values of bond lengths, bond angles, and dihedral angles.[13] The bonded terms refer to pairs, triplets, and quadruplets of bonded atoms, and include values for the effective spring constant for each potential. Most current force fields parameters use a fixed-charge model by which each atom is assigned one value for the atomic charge that is not affected by the local electrostatic environment.[10][14]

Force field parameterizations for simulations with maximum accuracy and transferability, e.g., IFF, follow a well-defined protocol.[1] The workflow may involve (1) retrieving an x-ray crystal structure or chemical formula, (2) defining atom types, (3) obtaining atomic charges, (4) assigning initial Lennard-Jones and bonded parameters, (5) computational tests of density and geometry relative to experimental reference data, (6) computational tests of energetic properties (surface energy,[15] hydration energy[16]) relative to experimental reference data, (7) secondary validation and refinement (thermal, mechanical, and diffusion properties).[17] Major iterative loops occur between steps (5) and (4), as well as between (6) and (4)/(3). The chemical interpretation of the parameters and reliable experimental reference data play a critical role.

The parameters for molecular simulations of biological macromolecules such as proteins, DNA, and RNA were often derived from observations for small organic molecules, which are more accessible for experimental studies and quantum calculations. Thereby, multiple issues arise, such as (1) unreliable atomic charges from quantum calculations may affect all computed properties and internal consistency, (2) data different derived from quantum mechanics for molecules in the gas phase may not be transferable for simulations in the condensed phase, (3) use of data for small molecules and application to larger polymeric structures involves uncertainty, (4) dissimilar experimental data with variation in accuracy and reference states (e.g. temperature) can cause deviations. As a result, divergent force field parameters have been reported for biological molecules. Experimental reference data included, for example, the enthalpy of vaporization (OPLS), enthalpy of sublimation, dipole moments, and various spectroscopic parameters.[4][12][18] Inconsistencies can be overcome by interpretation of all force field parameters and choosing a consistent reference state, for example, room temperature and atmospheric pressure.[1]

Several force fields also include no clear chemical rationale, parameterization protocol, incomplete validation of key properties (structures and energies), lack of interpretation of parameters, and of a discussion of uncertainties.[19] In these cases, large, random deviations of computed properties have been reported.

2.1. Methods

Some force fields include explicit models for polarizability, where a particle's effective charge can be influenced by electrostatic interactions with its neighbors. Core-shell models are common, which consist of a positively charged core particle, representing the polarizable atom, and a negatively charged particle attached to the core atom through a springlike harmonic oscillator potential.[20][21][22] Recent examples include polarizable models with virtual electrons that reproduce image charges in metals[23] and polarizable biomolecular force fields.[24] By adding such degrees of freedom for polarizability, the interpretation of the parameters becomes more difficult and increases the risk towards arbitrary fit parameters and decreased compatibility. The computational expense increases due to the need to repeatedly calculate the local electrostatic field.

Polarizable models perform well when it captures essential chemical features and the net atomic charge is relatively accurate (within ±10%).[1][25] In recent times, such models have been erroneously called "Drude Oscillator potentials".[26] An appropriate term for these models is "Lorentz oscillator models" since Lorentz[27] rather than Drude[28] proposed some form of attachment of electrons to nuclei.[23] Drude models assume unrestricted motion of the electrons, e.g., a free electron gas in metals.[28]

2.2. Parameterization

Historically, many approaches to parameterization of a forcefield have been employed. Numerous classical forcefields relied on relatively intransparent parameterization protocols, for example, using approximate quantum mechanical calculations, often in the gas phase, with the expectation of some correlation with condensed phase properties and empirical modifications of potentials to match experimental observables.[29][30][31] The protocols may not be reproducible and semi-automation often played a role to generate parameters, optimizing for speedy parameter generation and wide coverage, and not for chemical consistency, interpretability, reliability, and sustainability.

Similar, even more automated tools have become recently available to parameterize new force fields and assist users to develop their own parameter sets for chemistries which are not parameterized to date.[32][33] Efforts to provide open source codes and methods include openMM and openMD. The use of semi-automation or full automation, without input from chemical knowledge, is likely to increase inconsistencies at the level of atomic charges, for the assignment of remaining parameters, and likely to dilute the interpretability and performance of parameters.

The Interface force field (IFF) assumes one single energy expression for all compounds across the periodic (with 9-6 and 12-6 LJ options) and utilizes rigorous validation with standardized simulation protocols that enable full interpretability and compatibility of the parameters, as well as high accuracy and access to unlimited combinations of compounds.[1]

3. Transferability

Functional forms and parameter sets have been defined by the developers of interatomic potentials and feature variable degrees of self-consistency and transferability. When functional forms of the potential terms vary, the parameters from one interatomic potential function can typically not be used together with another interatomic potential function.[17] In some cases, modifications can be made with minor effort, for example, between 9-6 Lennard-Jones potentials to 12-6 Lennard-Jones potentials.[7] Transfers from Buckingham potentials to harmonic potentials, or from Embedded Atom Models to harmonic potentials, on the contrary, would require many additional assumptions and may not be possible.

4. Limitations

All interatomic potentials are based on approximations and experimental data, therefore often termed empirical. The performance varies from higher accuracy than density functional theory calculations, with access to million times larger systems and time scales, to random guesses depending on the force field.[34] The use of accurate representations of chemical bonding, combined with reproducible experimental data and validation, can lead to lasting interatomic potentials of high quality with much less parameters and assumptions in comparison to DFT-level quantum methods.[35][36]

Possible limitations include atomic charges, also called point charges. Most force fields rely on point charges to reproduce the electrostatic potential around molecules, which works less well for anisotropic charge distributions.[37] The remedy is that point charges have a clear interpretation,[10] and virtual electrons can be added to capture essential features of the electronic structure, such additional polarizability in metallic systems to describe the image potential, internal multipole moments in π-conjugated systems, and lone pairs in water.[38][39][40] Electronic polarization of the environment may be better included by using polarizable force fields[41][42] or using a macroscopic dielectric constant. However, application of one value of dielectric constant is a coarse approximation in the highly heterogeneous environments of proteins, biological membranes, minerals, or electrolytes.[43]

All types of van der Waals forces are also strongly environment-dependent because these forces originate from interactions of induced and "instantaneous" dipoles (see Intermolecular force). The original Fritz London theory of these forces applies only in a vacuum. A more general theory of van der Waals forces in condensed media was developed by A. D. McLachlan in 1963 and included the original London's approach as a special case.[44] The McLachlan theory predicts that van der Waals attractions in media are weaker than in vacuum and follow the like dissolves like rule, which means that different types of atoms interact more weakly than identical types of atoms.[45] This is in contrast to combinatorial rules or Slater-Kirkwood equation applied for development of the classical force fields. The combinatorial rules state that the interaction energy of two dissimilar atoms (e.g., C...N) is an average of the interaction energies of corresponding identical atom pairs (i.e., C...C and N...N). According to McLachlan's theory, the interactions of particles in media can even be fully repulsive, as observed for liquid helium,[44] however, the lack of vaporization and presence of a freezing point contradicts a theory of purely repulsive interactions. Measurements of attractive forces between different materials (Hamaker constant) have been explained by Jacob Israelachvili.[44] For example, "the interaction between hydrocarbons across water is about 10% of that across vacuum".[44] Such effects are represented in molecular dynamics through pairwise interactions that are spatially more dense in the condensed phase relative to the gas phase and reproduced once the parameters for all phases are validated to reproduce chemical bonding, density, and cohesive/surface energy.

Limitations have been strongly felt in protein structure refinement. The major underlying challenge is the huge conformation space of polymeric molecules, which grows beyond current computational feasibility when containing more than ~20 monomers.[46] Participants in Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) did not try to refine their models to avoid "a central embarrassment of molecular mechanics, namely that energy minimization or molecular dynamics generally leads to a model that is less like the experimental structure".[47] Force fields have been applied successfully for protein structure refinement in different X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy applications, especially using program XPLOR.[48] However, the refinement is driven mainly by a set of experimental constraints and the interatomic potentials serve mainly to remove interatomic hindrances. The results of calculations were practically the same with rigid sphere potentials implemented in program DYANA[49] (calculations from NMR data), or with programs for crystallographic refinement that use no energy functions at all. These shortcomings are related to interatomic potentials and to the inability to sample the conformation space of large molecules effectively.[50] Thereby also the development of parameters to tackle such large-scale problems requires new approaches. A specific problem area is homology modeling of proteins.[51] Meanwhile, alternative empirical scoring functions have been developed for ligand docking,[52] protein folding,[53][54][55] homology model refinement,[56] computational protein design,[57][58][59] and modeling of proteins in membranes.[60]

It was also argued that some protein force fields operate with energies that are irrelevant to protein folding or ligand binding.[41] The parameters of proteins force fields reproduce the enthalpy of sublimation, i.e., energy of evaporation of molecular crystals. However, protein folding and ligand binding are thermodynamically closer to crystallization, or liquid-solid transitions as these processes represent freezing of mobile molecules in condensed media.[61][62][63] Thus, free energy changes during protein folding or ligand binding are expected to represent a combination of an energy similar to heat of fusion (energy absorbed during melting of molecular crystals), a conformational entropy contribution, and solvation free energy. The heat of fusion is significantly smaller than enthalpy of sublimation.[44] Hence, the potentials describing protein folding or ligand binding need more consistent parameterization protocols, e.g., as described for IFF. Indeed, the energies of H-bonds in proteins are ~ -1.5 kcal/mol when estimated from protein engineering or alpha helix to coil transition data,[64][65] but the same energies estimated from sublimation enthalpy of molecular crystals were -4 to -6 kcal/mol,[66] which is related to re-forming existing hydrogen bonds and not forming hydrogen bonds from scratch. The depths of modified Lennard-Jones potentials derived from protein engineering data were also smaller than in typical potential parameters and followed the like dissolves like rule, as predicted by McLachlan theory.[41]

5. Widely Used Force Fields

Different force fields are designed for different purposes. All are implemented in various computers software.

MM2 was developed by Norman Allinger mainly for conformational analysis of hydrocarbons and other small organic molecules. It is designed to reproduce the equilibrium covalent geometry of molecules as precisely as possible. It implements a large set of parameters that is continuously refined and updated for many different classes of organic compounds (MM3 and MM4).[67][68][69][70][71]

CFF was developed by Arieh Warshel, Lifson, and coworkers as a general method for unifying studies of energies, structures, and vibration of general molecules and molecular crystals. The CFF program, developed by Levitt and Warshel, is based on the Cartesian representation of all the atoms, and it served as the basis for many subsequent simulation programs.

ECEPP was developed specifically for the modeling of peptides and proteins. It uses fixed geometries of amino acid residues to simplify the potential energy surface. Thus, the energy minimization is conducted in the space of protein torsion angles. Both MM2 and ECEPP include potentials for H-bonds and torsion potentials for describing rotations around single bonds. ECEPP/3 was implemented (with some modifications) in Internal Coordinate Mechanics and FANTOM.[72]

AMBER, CHARMM, and GROMOS have been developed mainly for molecular dynamics of macromolecules, although they are also commonly used for energy minimizing. Thus, the coordinates of all atoms are considered as free variables.

Interface Force Field (IFF)[73] was developed as the first consistent force field for compounds across the periodic table. It overcomes the known limitations of assigning consistent charges, utilizes standard conditions as a reference state, reproduces structures, energies, and energy derivatives, and quantifies limitations for all included compounds.[1][74] It is compatible with multiple force fields to simulate hybrid materials (CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS-AA, CFF, CVFF, GROMOS).

5.1. Classical

- AMBER (Assisted Model Building and Energy Refinement) – widely used for proteins and DNA.

- CFF (Consistent Force Field) – a family of forcefields adapted to a broad variety of organic compounds, includes force fields for polymers, metals, etc.

- CHARMM (Chemistry at HARvard Molecular Mechanics) – originally developed at Harvard, widely used for both small molecules and macromolecules

- COSMOS-NMR – hybrid QM/MM force field adapted to various inorganic compounds, organic compounds, and biological macromolecules, including semi-empirical calculation of atomic charges NMR properties. COSMOS-NMR is optimized for NMR-based structure elucidation and implemented in COSMOS molecular modelling package.[75]

- CVFF – also used broadly for small molecules and macromolecules.[12]

- ECEPP[76] – first force field for polypeptide molecules - developed by F.A. Momany, H.A. Scheraga and colleagues.[77][78]

- GROMOS (GROningen MOlecular Simulation) – a force field that comes as part of the GROMOS software, a general-purpose molecular dynamics computer simulation package for the study of biomolecular systems.[79] GROMOS force field A-version has been developed for application to aqueous or apolar solutions of proteins, nucleotides, and sugars. A B-version to simulate gas phase isolated molecules is also available.

- IFF (Interface Force Field) – First force field to cover metals, minerals, 2D materials, and polymers in one platform with cutting-edge accuracy and compatibility with many other force fields (CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS-AA, CFF, CVFF, GROMOS), includes 12-6 LJ and 9-6 LJ options[1][73]

- MMFF (Merck Molecular Force Field) – developed at Merck for a broad range of molecules.

- OPLS (Optimized Potential for Liquid Simulations) (variants include OPLS-AA, OPLS-UA, OPLS-2001, OPLS-2005, OPLS3e, OPLS4) – developed by William L. Jorgensen at the Yale University Department of Chemistry.

- QCFF/PI – A general force fields for conjugated molecules.[80][81]

- UFF (Universal Force Field) – A general force field with parameters for the full periodic table up to and including the actinoids, developed at Colorado State University.[19] The reliability is known to be poor due to lack of validation and interpretation of the parameters for nearly all claimed compounds, especially metals and inorganic compounds.[2][74]

5.2. Polarizable

- AMBER – polarizable force field developed by Jim Caldwell and coworkers.[82]

- AMOEBA (Atomic Multipole Optimized Energetics for Biomolecular Applications) – force field developed by Pengyu Ren (University of Texas at Austin) and Jay W. Ponder (Washington University).[83] AMOEBA force field is gradually moving to more physics-rich AMOEBA+.[84][85]

- CHARMM – polarizable force field developed by S. Patel (University of Delaware) and C. L. Brooks III (University of Michigan).[24][86] Based on the classical Drude oscillator developed by A. MacKerell (University of Maryland, Baltimore) and B. Roux (University of Chicago).[87][88]

- CFF/ind and ENZYMIX – The first polarizable force field[89] which has subsequently been used in many applications to biological systems.[42]

- COSMOS-NMR (Computer Simulation of Molecular Structure) – developed by Ulrich Sternberg and coworkers. Hybrid QM/MM force field enables explicit quantum-mechanical calculation of electrostatic properties using localized bond orbitals with fast BPT formalism.[90] Atomic charge fluctuation is possible in each molecular dynamics step.

- DRF90 developed by P. Th. van Duijnen and coworkers.[91]

- IFF (Interface Force Field) – includes polarizability for metals (Au, W) and pi-conjugated molecules[23][39][40]

- NEMO (Non-Empirical Molecular Orbital) – procedure developed by Gunnar Karlström and coworkers at Lund University (Sweden)[92]

- PIPF – The polarizable intermolecular potential for fluids is an induced point-dipole force field for organic liquids and biopolymers. The molecular polarization is based on Thole's interacting dipole (TID) model and was developed by Jiali Gao Gao Research Group | at the University of Minnesota.[93][94]

- Polarizable Force Field (PFF) – developed by Richard A. Friesner and coworkers.[95]

- SP-basis Chemical Potential Equalization (CPE) – approach developed by R. Chelli and P. Procacci.[96]

- PHAST - polarizable potential developed by Chris Cioce and coworkers.[97]

- ORIENT – procedure developed by Anthony J. Stone (Cambridge University) and coworkers.[98]

- Gaussian Electrostatic Model (GEM) – a polarizable force field based on Density Fitting developed by Thomas A. Darden and G. Andrés Cisneros at NIEHS; and Jean-Philip Piquemal at Paris VI University.[99][100][101]

- Atomistic Polarizable Potential for Liquids, Electrolytes, and Polymers(APPLE&P), developed by Oleg Borogin, Dmitry Bedrov and coworkers, which is distributed by Wasatch Molecular Incorporated.[102]

- Polarizable procedure based on the Kim-Gordon approach developed by Jürg Hutter and coworkers (University of Zürich)

- GFN-FF (Geometry, Frequency, and Noncovalent Interaction Force-Field) - a completely automated partially polarizable generic force-field for the accurate description of structures and dynamics of large molecules across the periodic table developed by Stefan Grimme and Sebastian Spicher at the University of Bonn.[103]

5.3. Reactive

- EVB (Empirical valence bond) – this reactive force field, introduced by Warshel and coworkers, is probably the most reliable and physically consistent way to use force fields in modeling chemical reactions in different environments.[according to whom?] The EVB facilitates calculating activation free energies in condensed phases and in enzymes.

- ReaxFF – reactive force field (interatomic potential) developed by Adri van Duin, William Goddard and coworkers. It is slower than classical MD (50x), needs parameter sets with specific validation, and has no validation for surface and interfacial energies. Parameters are non-interpretable. It can be used atomistic-scale dynamical simulations of chemical reactions.[11] Parallelized ReaxFF allows reactive simulations on >>1,000,000 atoms on large supercomputers.

5.4. Coarse-Grained

- DPD (Dissipative particle dynamics) - This is a method commonly applied in chemical engineering. It is typically used for studying the hydrodynamics of various simple and complex fluids which require consideration of time and length scales larger than those accessible to classical Molecular dynamics. The potential was originally proposed by Hoogerbrugge and Koelman [104][105] with later modifications by Español and Warren [106] The current state of the art was well documented in a CECAM workshop in 2008.[107] Recently, work has been undertaken to capture some of the chemical subtitles relevant to solutions. This has led to work considering automated parameterisation of the DPD interaction potentials against experimental observables.[33]

- MARTINI – a coarse-grained potential developed by Marrink and coworkers at the University of Groningen, initially developed for molecular dynamics simulations of lipids,[108] later extended to various other molecules. The force field applies a mapping of four heavy atoms to one CG interaction site and is parameterized with the aim of reproducing thermodynamic properties.

- SAFT - A top-down coarse-grained model developed in the Molecular Systems Engineering group at Imperial College London fitted to liquid phase densities and vapor pressures of pure compounds by using the SAFT equation of state.[109]

- SIRAH – a coarse-grained force field developed by Pantano and coworkers of the Biomolecular Simulations Group, Institut Pasteur of Montevideo, Uruguay; developed for molecular dynamics of water, DNA, and proteins. Free available for AMBER and GROMACS packages.

- VAMM (Virtual atom molecular mechanics) – a coarse-grained force field developed by Korkut and Hendrickson for molecular mechanics calculations such as large scale conformational transitions based on the virtual interactions of C-alpha atoms. It is a knowledge based force field and formulated to capture features dependent on secondary structure and on residue-specific contact information in proteins.[110]

5.5. Machine Learning

- ANI (Artificial Narrow Intelligence) is a transferable neural network potential, built from atomic environment vectors, and able to provide DFT accuracy in terms of energies.[111]

- FFLUX (originally QCTFF) [112] A set of trained Kriging models which operate together to provide a molecular force field trained on Atoms in molecules or Quantum chemical topology energy terms including electrostatic, exchange and electron correlation.[113][114]

- TensorMol, a mixed model, a Neural network provides a short-range potential, whilst more traditional potentials add screened long range terms.[114]

- Δ-ML not a force field method but a model that adds learnt correctional energy terms to approximate and relatively computationally cheap quantum chemical methods in order to provide an accuracy level of a higher order, more computationally expensive quantum chemical model.[115]

- SchNet a Neural network utilising continuous-filter convolutional layers, to predict chemical properties and potential energy surfaces.[116]

- PhysNet is a Neural Network-based energy function to predict energies, forces and (fluctuating) partial charges.[117]

5.6. Water

The set of parameters used to model water or aqueous solutions (basically a force field for water) is called a water model. Water has attracted a great deal of attention due to its unusual properties and its importance as a solvent. Many water models have been proposed; some examples are TIP3P, TIP4P,[118] SPC, flexible simple point charge water model (flexible SPC), ST2, and mW.[119] Other solvents and methods of solvent representation are also applied within computational chemistry and physics some examples are given on page Solvent model. Recently, novel methods for generating water models have been published.[120]

5.7. Modified Amino Acids

- Forcefield_PTM – An AMBER-based forcefield and webtool for modeling common post-translational modifications of amino acids in proteins developed by Chris Floudas and coworkers. It uses the ff03 charge model and has several side-chain torsion corrections parameterized to match the quantum chemical rotational surface.[121]

- Forcefield_NCAA - An AMBER-based forcefield and webtool for modeling common non-natural amino acids in proteins in condensed-phase simulations using the ff03 charge model.[122] The charges have been reported to be correlated with hydration free energies of corresponding side-chain analogs.[123]

5.8. Other

- LFMM (Ligand Field Molecular Mechanics)[124] - functions for the coordination sphere around transition metals based on the angular overlap model (AOM). Implemented in the Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) as DommiMOE and in Tinker[125]

- VALBOND - a function for angle bending that is based on valence bond theory and works for large angular distortions, hypervalent molecules, and transition metal complexes. It can be incorporated into other force fields such as CHARMM and UFF.

References

- "Thermodynamically consistent force fields for the assembly of inorganic, organic, and biological nanostructures: the INTERFACE force field". Langmuir 29 (6): 1754–65. February 2013. doi:10.1021/la3038846. PMID 23276161. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fla3038846

- "Force Field for Mica-Type Silicates and Dynamics of Octadecylammonium Chains Grafted to Montmorillonite". Chemistry of Materials 17 (23): 5658–5669. November 2005. doi:10.1021/cm0509328. ISSN 0897-4756. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fcm0509328

- Leach, Andrew (2001-01-30) (in en). Molecular Modelling: Principles and Applications (2nd ed.). Harlow: Prentice Hall. ISBN 9780582382107.

- Sun, Huai; Mumby, Stephen J.; Maple, Jon R.; Hagler, Arnold T. (April 1994). "An ab Initio CFF93 All-Atom Force Field for Polycarbonates". Journal of the American Chemical Society 116 (7): 2978–2987. doi:10.1021/ja00086a030. ISSN 0002-7863. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fja00086a030

- "CHARMM36 all-atom additive protein force field: validation based on comparison to NMR data". Journal of Computational Chemistry 34 (25): 2135–45. September 2013. doi:10.1002/jcc.23354. PMID 23832629. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3800559

- "Development and testing of a general amber force field". Journal of Computational Chemistry 25 (9): 1157–74. July 2004. doi:10.1002/jcc.20035. PMID 15116359. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fjcc.20035

- "A force field for tricalcium aluminate to characterize surface properties, initial hydration, and organically modified interfaces in atomic resolution". Dalton Transactions 43 (27): 10602–16. July 2014. doi:10.1039/c4dt00438h. PMID 24828263. https://dx.doi.org/10.1039%2Fc4dt00438h

- Gross, Kevin C.; Seybold, Paul G.; Hadad, Christopher M. (2002). "Comparison of different atomic charge schemes for predicting pKa variations in substituted anilines and phenols". International Journal of Quantum Chemistry 90 (1): 445–458. doi:10.1002/qua.10108. ISSN 0020-7608. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fqua.10108

- "Modeling the Partial Atomic Charges in Inorganometallic Molecules and Solids and Charge Redistribution in Lithium-Ion Cathodes". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 10 (12): 5640–50. December 2014. doi:10.1021/ct500790p. PMID 26583247. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fct500790p

- Heinz, Hendrik; Suter, Ulrich W. (November 2004). "Atomic Charges for Classical Simulations of Polar Systems". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 108 (47): 18341–18352. doi:10.1021/jp048142t. ISSN 1520-6106. Bibcode: 2004APS..MAR.Y8006H. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fjp048142t

- van Duin, Adri C. T.; Dasgupta, Siddharth; Lorant, Francois; Goddard, William A. (2001). "ReaxFF: A Reactive Force Field for Hydrocarbons". The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 105 (41): 9396–9409. doi:10.1021/jp004368u. Bibcode: 2001JPCA..105.9396V. http://www.wag.caltech.edu/publications/sup/pdf/471.pdf.

- "Structure and energetics of ligand binding to proteins: Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase-trimethoprim, a drug-receptor system". Proteins 4 (1): 31–47. 1988. doi:10.1002/prot.340040106. PMID 3054871. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fprot.340040106

- Dharmawardhana, Chamila C.; Kanhaiya, Krishan; Lin, Tzu-Jen; Garley, Amanda; Knecht, Marc R.; Zhou, Jihan; Miao, Jianwei; Heinz, Hendrik (2017-06-19). "Reliable computational design of biological-inorganic materials to the large nanometer scale using Interface-FF". Molecular Simulation 43 (13–16): 1394–1405. doi:10.1080/08927022.2017.1332414. ISSN 0892-7022. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080%2F08927022.2017.1332414

- Liu, Juan; Tennessen, Emrys; Miao, Jianwei; Huang, Yu; Rondinelli, James M.; Heinz, Hendrik (2018-05-31). "Understanding Chemical Bonding in Alloys and the Representation in Atomistic Simulations". The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 122 (26): 14996–15009. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b01891. ISSN 1932-7447. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Facs.jpcc.8b01891

- "Accurate Simulation of Surfaces and Interfaces of Face-Centered Cubic Metals Using 12−6 and 9−6 Lennard-Jones Potentials". The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 112 (44): 17281–17290. 2008-10-09. doi:10.1021/jp801931d. ISSN 1932-7447. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fjp801931d

- Emami, Fateme S.; Puddu, Valeria; Berry, Rajiv J.; Varshney, Vikas; Patwardhan, Siddharth V.; Perry, Carole C.; Heinz, Hendrik (2014-04-02). "Force Field and a Surface Model Database for Silica to Simulate Interfacial Properties in Atomic Resolution". Chemistry of Materials 26 (8): 2647–2658. doi:10.1021/cm500365c. ISSN 0897-4756. http://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/4652/1/4652_Perry.pdf.

- "Simulations of inorganic-bioorganic interfaces to discover new materials: insights, comparisons to experiment, challenges, and opportunities". Chemical Society Reviews 45 (2): 412–48. January 2016. doi:10.1039/c5cs00890e. PMID 26750724. https://dx.doi.org/10.1039%2Fc5cs00890e

- Jorgensen, William L.; Maxwell, David S.; Tirado-Rives, Julian (January 1996). "Development and Testing of the OPLS All-Atom Force Field on Conformational Energetics and Properties of Organic Liquids". Journal of the American Chemical Society 118 (45): 11225–11236. doi:10.1021/ja9621760. ISSN 0002-7863. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fja9621760

- "UFF, a full periodic table force field for molecular mechanics and molecular dynamics simulations". Journal of the American Chemical Society 114 (25): 10024–10035. December 1992. doi:10.1021/ja00051a040. ISSN 0002-7863.null

- "Theory of the Dielectric Constants of Alkali Halide Crystals". Physical Review 112 (1): 90–103. 1958-10-01. doi:10.1103/physrev.112.90. ISSN 0031-899X. Bibcode: 1958PhRv..112...90D. https://dx.doi.org/10.1103%2Fphysrev.112.90

- "Shell model simulations by adiabatic dynamics". Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 5 (8): 1031–1038. 1993-02-22. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/5/8/006. ISSN 0953-8984. Bibcode: 1993JPCM....5.1031M. https://dx.doi.org/10.1088%2F0953-8984%2F5%2F8%2F006

- Yu, Haibo; van Gunsteren, Wilfred F. (November 2005). "Accounting for polarization in molecular simulation". Computer Physics Communications 172 (2): 69–85. doi:10.1016/j.cpc.2005.01.022. ISSN 0010-4655. Bibcode: 2005CoPhC.172...69Y. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.cpc.2005.01.022

- "Insight into induced charges at metal surfaces and biointerfaces using a polarizable Lennard-Jones potential". Nature Communications 9 (1): 716. February 2018. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-03137-8. PMID 29459638. Bibcode: 2018NatCo...9..716G. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5818522

- "CHARMM fluctuating charge force field for proteins: I parameterization and application to bulk organic liquid simulations". Journal of Computational Chemistry 25 (1): 1–15. January 2004. doi:10.1002/jcc.10355. PMID 14634989. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fjcc.10355

- Lin, Tzu-Jen; Heinz, Hendrik (2016-02-26). "Accurate Force Field Parameters and pH Resolved Surface Models for Hydroxyapatite to Understand Structure, Mechanics, Hydration, and Biological Interfaces". The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 120 (9): 4975–4992. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b12504. ISSN 1932-7447. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Facs.jpcc.5b12504

- "An Empirical Polarizable Force Field Based on the Classical Drude Oscillator Model: Development History and Recent Applications". Chemical Reviews 116 (9): 4983–5013. May 2016. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00505. PMID 26815602. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4865892

- Lorentz, Hendrik A. (1905). "The Motion of Electrons in Metallic Bodies, I.". Proc. K. Ned. Akad. Wet. 7: 451. Bibcode: 1904KNAB....7..438L. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1904KNAB....7..438L

- Drude, Paul (1900). "Zur Elekronentheorie der Metalle. I. Teil.". Annalen der Physik 306 (3): 566–613. doi:10.1002/andp.19003060312. https://zenodo.org/record/1423977.

- "Optimization of the OPLS-AA Force Field for Long Hydrocarbons". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 8 (4): 1459–70. April 2012. doi:10.1021/ct200908r. PMID 26596756. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fct200908r

- "AMBER Force Field Parameters for the Naturally Occurring Modified Nucleosides in RNA". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 3 (4): 1464–75. July 2007. doi:10.1021/ct600329w. PMID 26633217. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fct600329w

- "A Glycam-Based Force Field for Simulations of Lipopolysaccharide Membranes: Parametrization and Validation". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 8 (11): 4719–31. November 2012. doi:10.1021/ct300534j. PMID 26605626. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fct300534j

- "Building Force Fields: An Automatic, Systematic, and Reproducible Approach". The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 5 (11): 1885–91. June 2014. doi:10.1021/jz500737m. PMID 26273869. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fjz500737m

- "Utilizing Machine Learning for Efficient Parameterization of Coarse Grained Molecular Force Fields". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 59 (10): 4278–4288. October 2019. doi:10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00646. PMID 31549507.null

- Emami, Fateme S.; Puddu, Valeria; Berry, Rajiv J.; Varshney, Vikas; Patwardhan, Siddharth V.; Perry, Carole C.; Heinz, Hendrik (2014-04-22). "Force Field and a Surface Model Database for Silica to Simulate Interfacial Properties in Atomic Resolution". Chemistry of Materials 26 (8): 2647–2658. doi:10.1021/cm500365c. ISSN 0897-4756. http://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/4652/1/4652_Perry.pdf.

- Ruiz, Victor G.; Liu, Wei; Tkatchenko, Alexandre (2016-01-15). "Density-functional theory with screened van der Waals interactions applied to atomic and molecular adsorbates on close-packed and non-close-packed surfaces". Physical Review B 93 (3): 035118. doi:10.1103/physrevb.93.035118. ISSN 2469-9950. Bibcode: 2016PhRvB..93c5118R. https://dx.doi.org/10.1103%2Fphysrevb.93.035118

- "Density-functional theory with screened van der Waals interactions for the modeling of hybrid inorganic-organic systems". Physical Review Letters 108 (14): 146103. April 2012. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.108.146103. PMID 22540809. Bibcode: 2012PhRvL.108n6103R. https://dx.doi.org/10.1103%2Fphysrevlett.108.146103

- "Charge Anisotropy: Where Atomic Multipoles Matter Most". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 10 (10): 4488–96. October 2014. doi:10.1021/ct5005565. PMID 26588145. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fct5005565

- Mahoney, Michael W.; Jorgensen, William L. (2000-05-22). "A five-site model for liquid water and the reproduction of the density anomaly by rigid, nonpolarizable potential functions". The Journal of Chemical Physics 112 (20): 8910–8922. doi:10.1063/1.481505. ISSN 0021-9606. Bibcode: 2000JChPh.112.8910M. https://dx.doi.org/10.1063%2F1.481505

- "Three-dimensional coordinates of individual atoms in materials revealed by electrontomography". Nature Materials 14 (11): 1099–103. November 2015. doi:10.1038/nmat4426. PMID 26390325. Bibcode: 2015NatMa..14.1099X. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fnmat4426

- "Carbon Nanotube Dispersion in Solvents and Polymer Solutions: Mechanisms, Assembly, and Preferences". ACS Nano 11 (12): 12805–12816. December 2017. doi:10.1021/acsnano.7b07684. PMID 29179536. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Facsnano.7b07684

- "Interatomic potentials and solvation parameters from protein engineering data for buried residues". Protein Science 11 (8): 1984–2000. August 2002. doi:10.1110/ps.0307002. PMID 12142453. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2373680

- "Modeling electrostatic effects in proteins". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics 1764 (11): 1647–76. November 2006. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2006.08.007. PMID 17049320. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.bbapap.2006.08.007

- "What are the dielectric "constants" of proteins and how to validate electrostatic models?". Proteins 44 (4): 400–17. September 2001. doi:10.1002/prot.1106. PMID 11484218. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fprot.1106

- "Intermolecular and Surface Forces". Elsevier. 2011. pp. iii. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-391927-4.10024-6. ISBN 978-0-12-391927-4. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fb978-0-12-391927-4.10024-6

- "Intermolecular forces in biology". Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics 34 (2): 105–267. May 2001. doi:10.1017/S0033583501003687. PMID 11771120. https://dx.doi.org/10.1017%2FS0033583501003687

- "Polyacrylonitrile Interactions with Carbon Nanotubes in Solution: Conformations and Binding as a Function of Solvent, Temperature, and Concentration". Advanced Functional Materials 29 (50): 1905247. 2019-10-03. doi:10.1002/adfm.201905247. ISSN 1616-301X. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fadfm.201905247

- "A brighter future for protein structure prediction". Nature Structural Biology 6 (2): 108–11. February 1999. doi:10.1038/5794. PMID 10048917. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2F5794

- "Molecular dynamics applied to X-ray structure refinement". Accounts of Chemical Research 35 (6): 404–12. June 2002. doi:10.1021/ar010034r. PMID 12069625. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Far010034r

- "Structure calculation of biological macromolecules from NMR data". Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics 31 (2): 145–237. May 1998. doi:10.1017/S0033583598003436. PMID 9794034. https://dx.doi.org/10.1017%2FS0033583598003436

- Ostermeir, Katja; Zacharias, Martin (January 2013). "163 Enhanced sampling of peptides and proteins with a new biasing replica exchange method". Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics 31 (sup1): 106. doi:10.1080/07391102.2013.786405. ISSN 0739-1102. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080%2F07391102.2013.786405

- "Assessment of homology-based predictions in CASP5". Proteins 53 Suppl 6: 352–68. 2003. doi:10.1002/prot.10543. PMID 14579324. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fprot.10543

- "Approaches to the description and prediction of the binding affinity of small-molecule ligands to macromolecular receptors". Angewandte Chemie 41 (15): 2644–76. August 2002. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20020802)41:15<2644::AID-ANIE2644>3.0.CO;2-O. PMID 12203463. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2F1521-3773%2820020802%2941%3A15%3C2644%3A%3AAID-ANIE2644%3E3.0.CO%3B2-O

- "Structural energetics of protein folding and binding". Current Opinion in Biotechnology 11 (1): 62–6. February 2000. doi:10.1016/s0958-1669(99)00055-5. PMID 10679345. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fs0958-1669%2899%2900055-5

- "Effective energy functions for protein structure prediction". Current Opinion in Structural Biology 10 (2): 139–45. April 2000. doi:10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00063-4. PMID 10753811. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fs0959-440x%2800%2900063-4

- Javidpour, Leili (2012). "Computer Simulations of Protein Folding". Computing in Science & Engineering 14 (2): 97–103. doi:10.1109/MCSE.2012.21. Bibcode: 2012CSE....14b..97J. https://dx.doi.org/10.1109%2FMCSE.2012.21

- "Improving physical realism, stereochemistry, and side-chain accuracy in homology modeling: Four approaches that performed well in CASP8". Proteins 77 Suppl 9: 114–22. 2009. doi:10.1002/prot.22570. PMID 19768677. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2922016

- "Energy functions for protein design". Current Opinion in Structural Biology 9 (4): 509–13. August 1999. doi:10.1016/S0959-440X(99)80072-4. PMID 10449371. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS0959-440X%2899%2980072-4

- "Energy estimation in protein design". Current Opinion in Structural Biology 12 (4): 441–6. August 2002. doi:10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00345-7. PMID 12163065. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fs0959-440x%2802%2900345-7

- Rohl, Carol A.; Strauss, Charlie E.M.; Misura, Kira M.S.; Baker, David (2004). "Protein Structure Prediction Using Rosetta". Numerical Computer Methods, Part D. Methods in Enzymology. 383. pp. 66–93. doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(04)83004-0. ISBN 9780121827885. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS0076-6879%2804%2983004-0

- "Positioning of proteins in membranes: a computational approach". Protein Science 15 (6): 1318–33. June 2006. doi:10.1110/ps.062126106. PMID 16731967. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2242528

- "Solid model compounds and the thermodynamics of protein unfolding". Journal of Molecular Biology 222 (3): 699–709. December 1991. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(91)90506-2. PMID 1660931. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2F0022-2836%2891%2990506-2

- "Theory of cooperative transitions in protein molecules. I. Why denaturation of globular protein is a first-order phase transition". Biopolymers 28 (10): 1667–80. October 1989. doi:10.1002/bip.360281003. PMID 2597723. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fbip.360281003

- "Thermodynamic stability of globular proteins: a reliable model from small molecule studies". Gazetta Chim. Italiana 126: 559–567. 1996.

- "Hydrogen bonding stabilizes globular proteins". Biophysical Journal 71 (4): 2033–9. October 1996. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79401-8. PMID 8889177. Bibcode: 1996BpJ....71.2033M. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1233669

- "Calorimetric determination of the enthalpy change for the alpha-helix to coil transition of an alanine peptide in water". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 88 (7): 2854–8. April 1991. doi:10.1073/pnas.88.7.2854. PMID 2011594. Bibcode: 1991PNAS...88.2854S. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=51338

- "Geometry of the intermolecular XH. cntdot.. cntdot.. cntdot. Y (X, Y= N, O) hydrogen bond and the calibration of empirical hydrogen-bond potentials.". The Journal of Physical Chemistry 98 (18): 4831–7. May 1994. doi:10.1021/j100069a010. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fj100069a010

- "Conformational analysis. 130. MM2. A hydrocarbon force field utilizing V1 and V2 torsional terms.". Journal of the American Chemical Society 99 (25): 8127–34. December 1977. doi:10.1021/ja00467a001. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fja00467a001

- "MM2 and MM3 home page". http://europa.chem.uga.edu/allinger/mm2mm3.html.

- "Molecular mechanics. The MM3 force field for hydrocarbons. 1.". Journal of the American Chemical Society 111 (23): 8551–66. November 1989. doi:10.1021/ja00205a001. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fja00205a001

- "Molecular mechanics. The MM3 force field for hydrocarbons. 2. Vibrational frequencies and thermodynamics.". Journal of the American Chemical Society 111 (23): 8566–75. November 1989. doi:10.1021/ja00205a002. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fja00205a002

- "Molecular mechanics. The MM3 force field for hydrocarbons. 3. The van der Waals' potentials and crystal data for aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons.". Journal of the American Chemical Society 111 (23): 8576–82. November 1989. doi:10.1021/ja00205a003. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fja00205a003

- "The program FANTOM for energy refinement of polypeptides and proteins using a Newton–Raphson minimizer in torsion angle space.". Biopolymers 29 (4–5): 679–94. March 1990. doi:10.1002/bip.360290403. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fbip.360290403

- "Interface Force Field (IFF)". Heinz Laboratory. 2 February 2016. https://bionanostructures.com/interface-md/.

- Mishra, Ratan K.; Mohamed, Aslam Kunhi; Geissbühler, David; Manzano, Hegoi; Jamil, Tariq; Shahsavari, Rouzbeh; Kalinichev, Andrey G.; Galmarini, Sandra et al. (December 2017). "A force field database for cementitious materials including validations, applications and opportunities". Cement and Concrete Research 102: 68–89. doi:10.1016/j.cemconres.2017.09.003. http://hal.in2p3.fr/in2p3-01633100/file/Mishra-CEMCON_2017-accepted.pdf.

- "Molecular mechanics with fluctuating atomic charges–a new force field with a semi-empirical charge calculation.". Molecular Modeling Annual 7 (4): 90–102. May 2001. doi:10.1007/s008940100008. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs008940100008

- "ECEPP". https://biohpc.cornell.edu/software/eceppak/README.html.

- "Energy parameters in polypeptides. VII. Geometric parameters, partial atomic charges, nonbonded interactions, hydrogen bond interactions, and intrinsic torsional potentials for the naturally occurring amino acids.". The Journal of Physical Chemistry 79 (22): 2361–81. October 1975. doi:10.1021/j100589a006. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fj100589a006

- "A new force field (ECEPP-05) for peptides, proteins, and organic molecules". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 110 (10): 5025–44. March 2006. doi:10.1021/jp054994x. PMID 16526746. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fjp054994x

- "GROMOS". https://www.igc.ethz.ch/gromos.html.

- "Quantum mechanical consistent force field (QCFF/PI) method: Calculations of energies, conformations and vibronic interactions of ground and excited states of conjugated molecules.". Israel Journal of Chemistry 11 (5): 709–17. 1973. doi:10.1002/ijch.197300067. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fijch.197300067

- QCFF/PI: A Program for the Consistent Force Field Evaluation of Equilibrium Geometries and Vibrational Frequencies of Molecules (Report). Indiana University: Quantum Chemistry Program Exchange. 1974. p. QCPE 247.

- "New-generation amber united-atom force field". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 110 (26): 13166–76. July 2006. doi:10.1021/jp060163v. PMID 16805629. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fjp060163v

- "Tinker Molecular Modeling Package". https://dasher.wustl.edu/tinker/.

- "Implementation of Geometry-Dependent Charge Flux into the Polarizable AMOEBA+ Potential". The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 11 (2): 419–426. January 2020. doi:10.1021/acs.jpclett.9b03489. PMID 31865706. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=7384396

- "AMOEBA+ Classical Potential for Modeling Molecular Interactions". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 15 (7): 4122–4139. July 2019. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.9b00261. PMID 31136175. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=6615954

- "CHARMM fluctuating charge force field for proteins: II protein/solvent properties from molecular dynamics simulations using a nonadditive electrostatic model". Journal of Computational Chemistry 25 (12): 1504–14. September 2004. doi:10.1002/jcc.20077. PMID 15224394. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fjcc.20077

- "Determination of Electrostatic Parameters for a Polarizable Force Field Based on the Classical Drude Oscillator". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 1 (1): 153–68. January 2005. doi:10.1021/ct049930p. PMID 26641126. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fct049930p

- "Simulating Monovalent and Divalent Ions in Aqueous Solution Using a Drude Polarizable Force Field". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 6 (3): 774–786. 2010. doi:10.1021/ct900576a. PMID 20300554. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2838399

- "Theoretical studies of enzymic reactions: dielectric, electrostatic and steric stabilization of the carbonium ion in the reaction of lysozyme". Journal of Molecular Biology 103 (2): 227–49. May 1976. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(76)90311-9. PMID 985660. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2F0022-2836%2876%2990311-9

- "New approach to the semiempirical calculation of atomic charges for polypeptides and large molecular systems.". Journal of Computational Chemistry 15 (5): 524–31. May 1994. doi:10.1002/jcc.540150505. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fjcc.540150505

- "DRF90: a polarizable force field.". Molecular Simulation 32 (6): 471–84. May 2006. doi:10.1080/08927020600631270. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080%2F08927020600631270

- "Accurate Intermolecular Potentials Obtained from Molecular Wave Functions: Bridging the Gap between Quantum Chemistry and Molecular Simulations". Chemical Reviews 100 (11): 4087–108. November 2000. doi:10.1021/cr9900477. PMID 11749341. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fcr9900477

- "A polarizable intermolecular potential function for simulation of liquid alcohols.". The Journal of Physical Chemistry 99 (44): 16460–7. November 1995. doi:10.1021/j100044a039. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fj100044a039

- "Development of a polarizable intermolecular potential function (PIPF) for liquid amides and alkanes". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 3 (6): 1878–1889. 2007. doi:10.1021/ct700146x. PMID 18958290. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2572772

- "A Polarizable Force Field and Continuum Solvation Methodology for Modeling of Protein-Ligand Interactions". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 1 (4): 694–715. July 2005. doi:10.1021/ct049855i. PMID 26641692. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fct049855i

- "A transferable polarizable electrostatic force field for molecular mechanics based on the chemical potential equalization principle.". The Journal of Chemical Physics 117 (20): 9175–89. November 2002. doi:10.1063/1.1515773. Bibcode: 2002JChPh.117.9175C. https://dx.doi.org/10.1063%2F1.1515773

- "A Polarizable and Transferable PHAST N2 Potential for Use in Materials Simulation". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 9 (12): 5550–7. December 2013. doi:10.1021/ct400526a. PMID 26592288. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fct400526a

- "Anthony Stone: Computer programs". http://www-stone.ch.cam.ac.uk/programs.html.

- "Anisotropic, Polarizable Molecular Mechanics Studies of Inter- and Intramolecular Interactions and Ligand-Macromolecule Complexes. A Bottom-Up Strategy". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 3 (6): 1960–1986. November 2007. doi:10.1021/ct700134r. PMID 18978934. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2367138

- "Towards a force field based on density fitting". The Journal of Chemical Physics 124 (10): 104101. March 2006. doi:10.1063/1.2173256. PMID 16542062. Bibcode: 2006JChPh.124j4101P. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2080832

- "Generalization of the Gaussian electrostatic model: extension to arbitrary angular momentum, distributed multipoles, and speedup with reciprocal space methods". The Journal of Chemical Physics 125 (18): 184101. November 2006. doi:10.1063/1.2363374. PMID 17115732. Bibcode: 2006JChPh.125r4101C. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2080839

- "Polarizable force field development and molecular dynamics simulations of ionic liquids". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 113 (33): 11463–78. August 2009. doi:10.1021/jp905220k. PMID 19637900. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fjp905220k

- "Robust Atomistic Modeling of Materials, Organometallic, and Biochemical Systems". Angewandte Chemie International Edition 59 (36): 15665–15673. September 2020. doi:10.1002/anie.202004239. PMID 32343883. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=7267649

- "Simulating Microscopic Hydrodynamic Phenomena with Dissipative Particle Dynamics". Europhysics Letters (EPL) 19 (3): 155–160. 1992. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/19/3/001. ISSN 0295-5075. Bibcode: 1992EL.....19..155H. https://dx.doi.org/10.1209%2F0295-5075%2F19%2F3%2F001

- "Dynamic Simulations of Hard-Sphere Suspensions Under Steady Shear". Europhysics Letters (EPL) 21 (3): 363–368. 1993. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/21/3/018. ISSN 0295-5075. Bibcode: 1993EL.....21..363K. https://dx.doi.org/10.1209%2F0295-5075%2F21%2F3%2F018

- "Statistical Mechanics of Dissipative Particle Dynamics". Europhysics Letters (EPL) 30 (4): 191–196. 1995. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/30/4/001. ISSN 0295-5075. Bibcode: 1995EL.....30..191E.null

- Dissipative Particle Dynamics: Addressing deficiencies and establishing new frontiers, CECAM workshop, July 16–18, 2008, Lausanne, Switzerland. http://www.cecam.org/workshop-0-188.html

- "The MARTINI force field: coarse grained model for biomolecular simulations". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 111 (27): 7812–24. July 2007. doi:10.1021/jp071097f. PMID 17569554. https://pure.rug.nl/ws/files/6707449/2007JPhysChemBMarrink.pdf.

- "SAFT". http://molecularsystemsengineering.org/saft.html.

- "A force field for virtual atom molecular mechanics of proteins". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106 (37): 15667–72. September 2009. doi:10.1073/pnas.0907674106. PMID 19717427. Bibcode: 2009PNAS..10615667K. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2734882

- "ANI-1: an extensible neural network potential with DFT accuracy at force field computational cost". Chemical Science 8 (4): 3192–3203. April 2017. doi:10.1039/C6SC05720A. PMID 28507695. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5414547

- "Description of Potential Energy Surfaces of Molecules Using FFLUX Machine Learning Models". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 15 (1): 116–126. January 2019. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.8b00806. PMID 30507180. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Facs.jctc.8b00806

- "Multipolar Electrostatic Energy Prediction for all 20 Natural Amino Acids Using Kriging Machine Learning". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 12 (6): 2742–51. June 2016. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00457. PMID 27224739. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Facs.jctc.6b00457

- "Machine Learning of Dynamic Electron Correlation Energies from Topological Atoms". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 14 (1): 216–224. January 2018. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.7b01157. PMID 29211469. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Facs.jctc.7b01157

- "Big Data Meets Quantum Chemistry Approximations: The Δ-Machine Learning Approach". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 11 (5): 2087–96. May 2015. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00099. PMID 26574412. Bibcode: 2015arXiv150304987R. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Facs.jctc.5b00099

- "SchNet - A deep learning architecture for molecules and materials". The Journal of Chemical Physics 148 (24): 241722. June 2018. doi:10.1063/1.5019779. PMID 29960322. Bibcode: 2018JChPh.148x1722S. https://dx.doi.org/10.1063%2F1.5019779

- O. T. Unke and M. Meuwly (2019). "PhysNet: A Neural Network for Predicting Energies, Forces, Dipole Moments, and Partial Charges". J. Chem. Theo. Chem. 15 (6): 3678–3693. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.9b00181. PMID 31042390. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Facs.jctc.9b00181

- "A general purpose model for the condensed phases of water: TIP4P/2005". The Journal of Chemical Physics 123 (23): 234505. December 2005. doi:10.1063/1.2121687. PMID 16392929. Bibcode: 2005JChPh.123w4505A. https://dx.doi.org/10.1063%2F1.2121687

- "Water modeled as an intermediate element between carbon and silicon". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 113 (13): 4008–16. April 2009. doi:10.1021/jp805227c. PMID 18956896. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fjp805227c

- "A FFLUX Water Model: Flexible, Polarizable and with a Multipolar Description of Electrostatics". Journal of Computational Chemistry 41 (7): 619–628. March 2020. doi:10.1002/jcc.26111. PMID 31747059. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=7004022

- "Ab Initio Charge and AMBER Forcefield Parameters for Frequently Occurring Post-Translational Modifications". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 9 (12): 5653–5674. December 2013. doi:10.1021/ct400556v. PMID 24489522. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3904396

- "Forcefield_NCAA: ab initio charge parameters to aid in the discovery and design of therapeutic proteins and peptides with unnatural amino acids and their application to complement inhibitors of the compstatin family". ACS Synthetic Biology 3 (12): 855–69. December 2014. doi:10.1021/sb400168u. PMID 24932669. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4277759

- "Hydration free energies calculated using the AMBER ff03 charge model for natural and unnatural amino acids and multiple water models". Computers & Chemical Engineering 71: 745–752. 2014. doi:10.1016/j.compchemeng.2014.07.017. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.compchemeng.2014.07.017

- Deeth, Robert J. (2001). "The ligand field molecular mechanics model and the stereoelectronic effects of d and s electrons". Coordination Chemistry Reviews 212 (212): 11–34. doi:10.1016/S0010-8545(00)00354-4. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS0010-8545%2800%2900354-4

- "Integration of Ligand Field Molecular Mechanics in Tinker". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 55 (6): 1282–90. June 2015. doi:10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00098. PMID 25970002. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Facs.jcim.5b00098