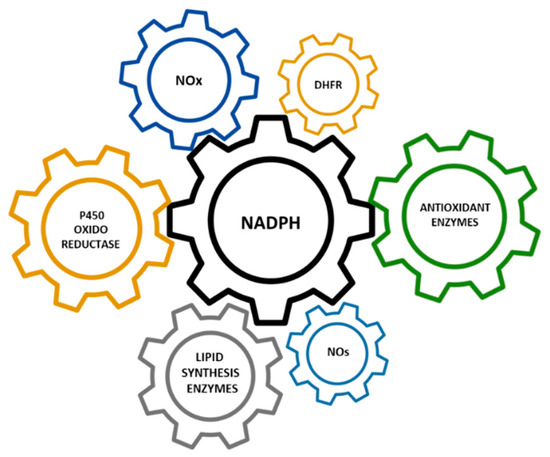

Hypomorphic Glucose 6-P dehydrogenase (G6PD) catalyzes the rate-limiting step in the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), which provides the precursors of nucleotide synthesis for DNA replication as well as reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH). NADPH is involved in the detoxification of cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) and de novo lipid synthesis. An association between increased PPP activity and the stimulation of cell growth has been reported in different tissues including the skeletal muscle, liver, and kidney. PPP activity is increased in skeletal muscle during embryogenesis, denervation, ischemia, mechanical overload, the injection of myonecrotic agents, and physical exercise. In fact, the highest relative increase in the activity of skeletal muscle enzymes after one bout of exhaustive exercise is that of G6PD, suggesting that the activation of the PPP occurs in skeletal muscle to provide substrates for muscle repair. The age-associated loss in muscle mass and strength leads to a decrease in G6PD activity and protein content in skeletal muscle. G6PD overexpression in Drosophila Melanogaster and mice protects against metabolic stress, oxidative damage, and age-associated functional decline, and results in an extended median lifespan.

- G6PD

- pentose phosphate pathway

- NADPH

- skeletal muscle

- physical training

- aging

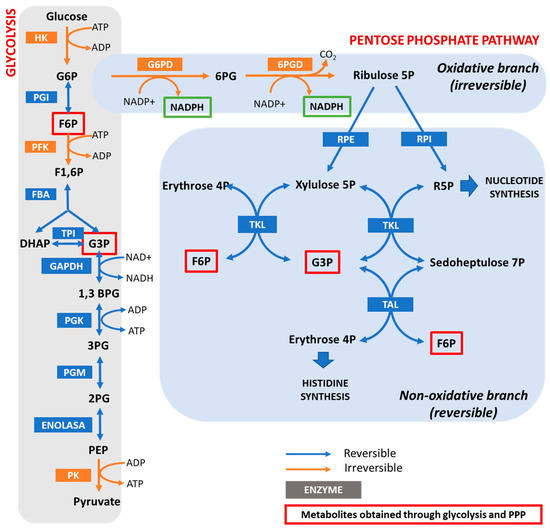

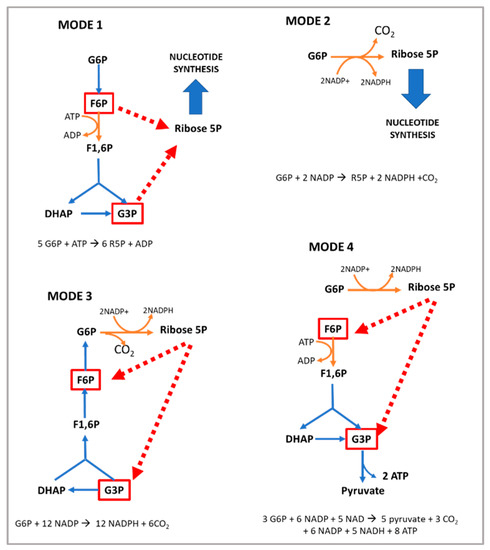

1. The Pentose Phosphate Pathway and the Regulation of Glucose 6-P PDehydrogenase

2. Loss of Function Models for G6PD

3. G6PD and Cell Growth

The modulation of cell survival and cell growth relies on intracellular redox regulation [28][65]. As mentioned in the previous sections of this manuscript, NADPH—the principal intracellular reductant—is a critical modulator of redox potential. In 1999, Dr. Stanton and coworkers found that G6PD plays an important role in cell death by regulating intracellular redox levels [29][66]. The inhibition of G6PD by both dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and 6-aminonicotinamide (6-ANAD) augmented cell death triggered by serum deprivation and oxidative stress, while the overexpression of G6PD in a cell line conferred resistance to H2O2-induced cell death. Previously, in G6PD-deficient cell lines, it was reported that these cells had decreased cloning efficiencies and growth rates and were highly sensitive to ROS when compared to cells expressing endogenous levels of the enzyme [30][67]. Consistent with these results, an association between the stimulation of cell growth in different tissues and increased PPP activity has also been reported [31][68]. Kidney hypertrophy due to unilateral nephrectomy is associated with increased G6PD activity [32][69], while the growth of rat liver cells stimulated by growth hormone is also associated with an increase in G6PD activity [33][70].

4. G6PD in the Regeneration of Skeletal Muscle after Damage

The hexose monophosphate shunt is considered an almost negligible pathway in normal muscle. For this reason, the function of G6PD in skeletal muscle has been poorly investigated. In vitro studies have shown that, under normal conditions, glucose breakdown takes place via both the Embden–Meyerhof pathway and the PPP in the liver, pancreas, arterial wall, kidney, spleen, and adrenals. However, in the central nervous system and cardiac and striated muscle, it is metabolized mainly via the glycolytic route [34][72]. In addition, several conditions increase the activity of the PPP in skeletal muscle: (i) embryogenesis [35][73]; (ii) denervation; (iii) ischemia; (iv) hypertrophy; (v) the injection of myonecrotic agents with local degeneration effects [36][37][74,75]; and (vi) physical exercise [23][32]. The injection of myonecrotic agents (bupivacaine, Marcaine, or cardiotoxin) induces a rapid (8 h) and dramatic (6–9-fold) increase in the activities of G6PD and 6PGD during regeneration after muscle destruction. By using histological techniques [38][39][76,77], it has been shown that G6PD is localized within muscle cells in regenerating muscle; thus, the enhanced enzyme activity resides in the muscle fibers themselves for at least the first 6–8 h after Marcaine injection. After that time, phagocytic cells contribute to the increase in enzyme activity [36][74]. The enhanced activities of G6PD and 6PGD likely reflect accelerated glucose utilization for the production of nucleic acids and lipids [37][40][41][42][75,78,79,80]. In this regard, increased quantities of RNA have been noted in a number of studies on muscle regeneration [43][44][45][81,82,83]. The enhancement of the PPP is important for anabolic processes in the initial stages of skeletal muscle regeneration; however, the role of G6PD in skeletal muscle goes beyond biosynthetic processes.5. Positive Regulators of G6PD Activity in Skeletal Muscle

As shown in Table 12, G6PD can be regulated by pharmacological, nutritional, and physiological interventions, such as physical exercise [31][68].

| Positive Regulators | Negative Regulators |

|---|---|

| Acetylation [46][130] | 5′ adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) [47][131] |

| G6PD activator AG1 [48][132] | Aldosterone [49][133] |

| AKT [50][134] | Angiotensin II [51][120] |

| ATM serine/threonine kinase (ATM) [52][135] | Arachidonic acid [53][136] |

| Benfotiamine (vitamin B1 analog) [54][55][110,137] | Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) [56][138] |

| Proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src (c-Src) [57][25] | cAMP-dependent protein kinase A [56][138] |

| cGMP-dependent protein kinase G [58][139] | cAMP response element modulator (CREM) [49][133] |

| Cyclin D3-CDK6 [59][140] | Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) [60][141] |

| Epidermal growth factor (EGF) [61][142] | miR-122 and miR-1 [62][143] |

| Estrogens [54][110] | p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase [53][136] |

| Exercise [23][32] | p53 [63][144] |

| Glycosylation [64][145] | Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) [65][146] |

| Growth hormone [54][110] | TP53 [63][144] |

| Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) [66][147] | Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) [31][68] |

| Heat shock protein 27 (Hsp27) [67][148] | |

| Hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) [68][149] | |

| Inhibitor of DNA binding 1 (ID1) [69][150] | |

| Insulin [70][151] | |

| Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) [71][152] | |

| Nuclear-factor-E2-related factor (Nrf2) [72][153] | |

| Ribosomal protein S6 kinase beta-1 (p70S6K) [54][110] | |

| Serine/threonine-protein kinase PAK 4 (PAK4) [73][154] | |

| Protein disulfide isomerase family A, member 3 pseudogene (PDIA3P) [74][155] | |

| Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI-3K) [50][134] | |

| Phospholipase C [54][110] | |

| Phospholipase C-γ [75][156] | |

| Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) [75][156] | |

| Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK-1) [76][157] | |

| Ras-GTPase [31][68] | |

| S6 kinase [77][158] | |

| Snail [78][159] | |

| Sterol-responsive element bindingprotein (SREBP) 1 [31][68] | |

| Stobadine [79][160] | |

| TAp73 [80][161] | |

| Testosterone [54][110] | |

| Transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β1) [81][162] | |

| TP53-induced glycolysis and apoptosis regulator (TIGAR) [82][163] | |

| Vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF) [57][25] | |

| Vitamin D [83][164] | |

| Vitamin E [79][160] |