Neospora caninum is a well-known protist parasite of cattle and is considered to be one of the most relevant abortifacient agents responsible for significant economic losses in the bovine industry. The first report of this parasite in sheep was over 30 years ago, when it was described in a weak lamb with neurological signs that had been misdiagnosed as toxoplasmosis 15 years previously, due to the similarity of the associated histological lesions. Since this initial description, ovine neosporosis has typically been considered as infrequent, until a decade ago, when awareness of its potential as a reproductive disease in sheep was raised. However, there are many knowledge deficits with respect to its economic impact and geographic distribution, due to the paucity of published studies. Additionally, the pathogenesis of the disease remains poorly understood, as most experimental studies of ovine neosporosis use it as model of exogenous bovine neosporosis. Furthermore, experimental challenge is primarily via parenteral inoculation of tachyzoites—a route that might not accurately reproduce the events of the natural disease, as it is acquired through the ingestion of sporulated oocysts. In fact, there is still scarce information on the pathogenesis of ovine neosporosis after natural or experimental oocyst ingestion, or on its mechanism of transplacental transmission.

- sheep

- neosporosis

- prevalence

- diagnosis

1. Life Cycle and Transmission

2. Clinical Signs and Lesions

3. Diagnosis

3.1. DNA Detection by PCR

3.2. Serology

4. Prevalence

4.1. America

4.2. Africa

4.3. Asia

4.4. Europe

4.5. Oceania

4.6. Experimental Design Variables and Risk Factors

References

- Dubey, J.P. Review of Neospora caninum and Neosporosis in Animals. Korean J. Parasitol. 2003, 41, 1–16.

- O’Handley, R.; Liddell, S.; Parker, C.; Jenkins, M.C.; Dubey, J.P. Experimental Infection of Sheep with Neospora caninum Oocysts. J. Parasitol. 2002, 88, 1120–1123.

- Gutiérrez-Expósito, D.; González-Warleta, M.; Espinosa, J.; Vallejo-García, R.; Castro-Hermida, J.A.; Calvo, C.; Ferreras, M.C.; Pérez, V.; Benavides, J.; Mezo, M. Maternal Immune Response in the Placenta of Sheep during Recrudescence of Natural Congenital Infection of Neospora caninum. Vet. Parasitol. 2020, 285, 109204.

- Sánchez-Sánchez, R.; Vázquez-Calvo, Á.; Fernández-Escobar, M.; Regidor-Cerrillo, J.; Benavides, J.; Gutiérrez, J.; Gutiérrez-Expósito, D.; Crespo-Ramos, F.J.; Ortega-Mora, L.M.; Álvarez-García, G. Dynamics of Neospora caninum-Associated Abortions in a Dairy Sheep Flock and Results of a Test-and-Cull Control Programme. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1518.

- Almería, S.; López-Gatius, F. Bovine Neosporosis: Clinical and Practical Aspects. Res. Vet. Sci. 2013, 95, 303–309.

- Dubey, J.P.; Hemphill, A.; Calero-Bernal, R.; Schares, G. Neosporosis in Animals, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-4987-5254-1.

- Costa, R.C.; Orlando, D.R.; Abreu, C.C.; Nakagaki, K.Y.R.; Mesquita, L.P.; Nascimento, L.C.; Silva, A.C.; Maiorka, P.C.; Peconick, A.P.; Raymundo, D.L.; et al. Histological and Immunohistochemical Characterization of the Inflammatory and Glial Cells in the Central Nervous System of Goat Fetuses and Adult Male Goats Naturally Infected with Neospora caninum. BMC Vet. Res. 2014, 10, 291.

- Mesquita, L.P.; Nogueira, C.I.; Costa, R.C.; Orlando, D.R.; Bruhn, F.R.P.; Lopes, P.F.R.; Nakagaki, K.Y.R.; Peconick, A.P.; Seixas, J.N.; Bezerra, P.S.; et al. Antibody Kinetics in Goats and Conceptuses Naturally Infected with Neospora caninum. Vet. Parasitol 2013, 196, 327–333.

- González-Warleta, M.; Castro-Hermida, J.A.; Regidor-Cerrillo, J.; Benavides, J.; Álvarez-García, G.; Fuertes, M.; Ortega-Mora, L.M.; Mezo, M. Neospora caninum Infection as a Cause of Reproductive Failure in a Sheep Flock. Vet. Res. 2014, 45, 1–9.

- González-Warleta, M.; Castro-Hermida, J.A.; Calvo, C.; Pérez, V.; Gutiérrez-Expósito, D.; Regidor-Cerrillo, J.; Ortega-Mora, L.M.; Mezo, M. Endogenous Transplacental Transmission of Neospora caninum during Successive Pregnancies across Three Generations of Naturally Infected Sheep. Vet. Res. 2018, 49, 106.

- Williams, D.J.L.; Hartley, C.S.; Björkman, C.; Trees, A.J. Endogenous and Exogenous Transplacental Transmission of Neospora Caninum—How the Route of Transmission Impacts on Epidemiology and Control of Disease. Parasitology 2009, 136, 1895–1900.

- Romo-Gallegos, J.M.; Cruz-Vázquez, C.; Medina-Esparza, L.; Ramos-Parra, M.; Romero-Salas, D. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Neospora caninum Infection in Ovine Flocks of Central-Western Mexico. Acta Vet. Hung. 2019, 67, 51–59.

- Castañeda-Hernández, A.; Cruz-Vázquez, C.; Medina-Esparza, L. Neospora caninum: Seroprevalence and DNA Detection in Blood of Sheep from Aguascalientes, Mexico. Small Rumin. Res. 2014, 119, 182–186.

- Okeoma, C.M.; Stowell, K.M.; Williamson, N.B.; Pomroy, W.E. Neospora caninum: Quantification of DNA in the Blood of Naturally Infected Aborted and Pregnant Cows Using Real-Time PCR. Exp. Parasitol. 2005, 110, 48–55.

- Santana, O.I.; Cruz-Vázquez, C.; Medina-Esparza, L.; Ramos Parra, M.; Castellanos Morales, C.; Quezada Gallardo, D. Neospora caninum: DNA Detection in Blood during First Gestation of Naturally Infected Heifers. Vet. México 2010, 41, 131–137.

- Figliuolo, L.P.C.; Kasai, N.; Ragozo, A.M.A.; de Paula, V.S.O.; Dias, R.A.; Souza, S.L.P.; Gennari, S.M. Prevalence of Anti-Toxoplasma gondii and Anti-Neospora caninum Antibodies in Ovine from São Paulo State, Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2004, 123, 161–166.

- Amdouni, Y.; Rjeibi, M.R.; Awadi, S.; Rekik, M.; Gharbi, M. First Detection and Molecular Identification of Neospora caninum from Naturally Infected Cattle and Sheep in North Africa. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018, 65, 976–982.

- Sun, L.-X.; Liang, Q.-L.; Nie, L.-B.; Hu, X.-H.; Li, Z.; Yang, J.-F.; Zou, F.-C.; Zhu, X.-Q. Serological Evidence of Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum Infection in Black-Boned Sheep and Goats in Southwest China. Parasitol. Int. 2020, 75, 102041.

- Stelzer, S.; Basso, W.; Benavides Silván, J.; Ortega-Mora, L.M.; Maksimov, P.; Gethmann, J.; Conraths, F.J.; Schares, G. Toxoplasma gondii Infection and Toxoplasmosis in Farm Animals: Risk Factors and Economic Impact. Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2019, 15, e00037.

- Romanelli, P.R.; Freire, R.L.; Vidotto, O.; Marana, E.R.M.; Ogawa, L.; De Paula, V.S.O.; Garcia, J.L.; Navarro, I.T. Prevalence of Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii in Sheep and Dogs from Guarapuava Farms, Paraná State, Brazil. Res. Vet. Sci. 2007, 82, 202–207.

- Gharekhani, J.; Yakhchali, M.; Esmaeilnejad, B.; Mardani, K.; Majidi, G.; Sohrabi, A.; Berahmat, R.; Hazhir Alaei, M. Seroprevalence and Risk Factors of Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii in Small Ruminants in Southwest of Iran. Arch. Razi Inst. 2018, 73, 305–310.

- Conraths, F.J.; Gottstein, B. Protozoal Abortion in Farm Ruminants: Guidelines for Diagnosis and Control, 1st ed.; Ortega-Mora, L.M., Gottstein, B., Conraths, F.J., Buxton, D., Eds.; CABI International: Oxford, UK, 2007.

- Nie, L.-B.; Cong, W.; Zou, Y.; Zhou, D.-H.; Liang, Q.-L.; Zheng, W.-B.; Ma, J.-G.; Du, R.; Zhu, X.-Q. First Report of Seroprevalence and Risk Factors of Neospora caninum Infection in Tibetan Sheep in China. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 2098908.

- Ueno, T.E.H.; Gonçalves, V.S.P.; Heinemann, M.B.; Dilli, T.L.B.; Akimoto, B.M.; de Souza, S.L.P.; Gennari, S.M.; Soares, R.M. Prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum Infections in Sheep from Federal District, Central Region of Brazil. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2009, 41, 547–552.

- Gazzonis, A.L.; Alvarez Garcia, G.; Zanzani, S.A.; Ortega Mora, L.M.; Invernizzi, A.; Manfredi, M.T. Neospora caninum Infection in Sheep and Goats from North-Eastern Italy and Associated Risk Factors. Small Rumin. Res. 2016, 140, 7–12.

- Amouei, A.; Sharif, M.; Sarvi, S.; Bagheri Nejad, R.; Aghayan, S.A.; Hashemi-Soteh, M.B.; Mizani, A.; Hosseini, S.A.; Gholami, S.; Sadeghi, A.; et al. Aetiology of Livestock Fetal Mortality in Mazandaran Province, Iran. PeerJ 2019, 6, e5920.

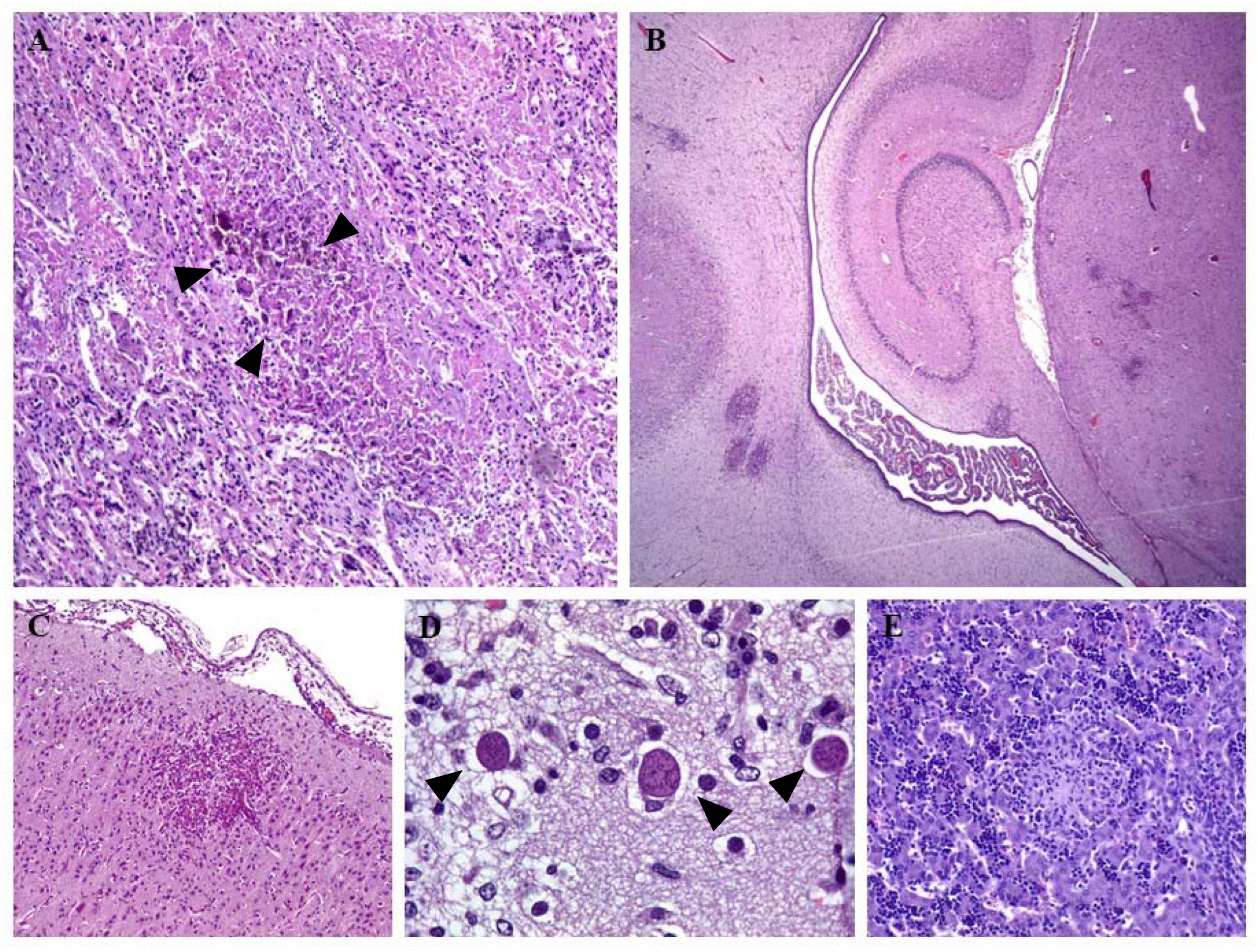

- Al-Shaeli, S.J.J.; Ethaeb, A.M.; Gharban, H.A.J. Molecular and Histopathological Identification of Ovine Neosporosis (Neospora caninum) in Aborted Ewes in Iraq. Vet. World 2020, 13, 597–603.

- Hässig, M.; Sager, H.; Reitt, K.; Ziegler, D.; Strabel, D.; Gottstein, B. Neospora caninum in Sheep: A Herd Case Report. Vet. Parasitol. 2003, 117, 213–220.

- Buxton, D. Protozoan Infections (Toxoplasma gondii, Neospora caninum and Sarcocystis Spp.) in Sheep and Goats: Recent Advances. Vet. Res. 1998, 29, 289–310.

- Arranz-Solís, D.; Benavides, J.; Regidor-Cerrillo, J.; Fuertes, M.; Ferre, I.; Ferreras, M.D.C.; Collantes-Fernández, E.; Hemphill, A.; Pérez, V.; Ortega-Mora, L.M. Influence of the Gestational Stage on the Clinical Course, Lesional Development and Parasite Distribution in Experimental Ovine Neosporosis. Vet. Res. 2015, 46, 19.

- Meixner, N.; Sommer, M.F.; Scuda, N.; Matiasek, K.; Müller, M. Comparative Aspects of Laboratory Testing for the Detection of Toxoplasma gondii and Its Differentiation from Neospora caninum as the Etiologic Agent of Ovine Abortion. J. Vet. Diagn Invest. 2020, 32, 898–907.

- Hecker, Y.P.; Morrell, E.L.; Fiorentino, M.A.; Gual, I.; Rivera, E.; Fiorani, F.; Dorsch, M.A.; Gos, M.L.; Pardini, L.L.; Scioli, M.V.; et al. Ovine Abortion by Neospora caninum: First Case Reported in Argentina. Acta Parasit. 2019, 64, 950–955.

- Moreno, B.; Collantes-Fernández, E.; Villa, A.; Navarro, A.; Regidor-Cerrillo, J.; Ortega-Mora, L.M. Occurrence of Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii Infections in Ovine and Caprine Abortions. Vet. Parasitol. 2012, 187, 312–318.

- McAllister, M.M.; McGuire, A.M.; Jolley, W.R.; Lindsay, D.S.; Trees, A.J.; Stobart, R.H. Experimental Neosporosis in Pregnant Ewes and Their Offspring. Vet. Pathol. 1996, 33, 647–655.

- Bishop, S.; King, J.; Windsor, P.; Reichel, M.P.; Ellis, J.; Slapeta, J. The First Report of Ovine Cerebral Neosporosis and Evaluation of Neospora caninum Prevalence in Sheep in New South Wales. Vet. Parasitol 2010, 170, 137–142.

- Kobayashi, Y.; Yamada, M.; Omata, Y.; Koyama, T.; Saito, A.; Matsuda, T.; Okuyama, K.; Fujimoto, S.; Furuoka, H.; Matsui, T. Naturally-Occurring Neospora caninum Infection in an Adult Sheep and Her Twin Fetuses. J. Parasitol 2001, 87, 434–436.

- Howe, L.; Collett, M.G.; Pattison, R.S.; Marshall, J.; West, D.M.; Pomroy, W.E. Potential Involvement of Neospora caninum in Naturally Occurring Ovine Abortions in New Zealand. Vet. Parasitol. 2012, 185, 64–71.

- Alcalá-Gómez, J.; Medina-Esparza, L.; Vitela-Mendoza, I.; Cruz-Vázquez, C.; Quezada-Tristán, T.; Gómez-Leyva, J.F. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii Infection in Breeding Ewes from Central Western Mexico. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2022, 54, 225.

- Arbabi, M.; Abdoli, A.; Dalimi, A.; Pirestani, M. Identification of Latent Neosporosis in Sheep in Tehran, Iran by Polymerase Chain Reaction Using Primers Specific for the Nc-5 Gene. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 2016, 83, e1–e7.

- Dessì, G.; Tamponi, C.; Pasini, C.; Porcu, F.; Meloni, L.; Cavallo, L.; Sini, M.F.; Knoll, S.; Scala, A.; Varcasia, A. A Survey on Apicomplexa Protozoa in Sheep Slaughtered for Human Consumption. Parasitol. Res. 2022, 121, 1437–1445.

- Santos, S.L.; de Souza Costa, K.; Gondim, L.Q.; da Silva, M.S.A.; Uzêda, R.S.; Abe-Sandes, K.; Gondim, L.F.P. Investigation of Neospora caninum, Hammondia Sp., and Toxoplasma gondii in Tissues from Slaughtered Beef Cattle in Bahia, Brazil. Parasitol. Res. 2010, 106, 457–461.

- Bartley, P.M.; Katzer, F.; Rocchi, M.S.; Maley, S.W.; Benavides, J.; Nath, M.; Pang, Y.; Cantón, G.; Thomson, J.; Chianini, F.; et al. Development of Maternal and Foetal Immune Responses in Cattle Following Experimental Challenge with Neospora caninum at Day 210 of Gestation. Vet. Res. 2013, 44, 91.

- Buxton, D.; Maley, S.W.; Wright, S.; Thomson, K.M.; Rae, A.G.; Innes, E.A. The Pathogenesis of Experimental Neosporosis in Pregnant Sheep. J. Comp. Pathol. 1998, 118, 267–279.

- Yamage, M.; Flechtner, O.; Gottstein, B. Neospora caninum: Specific Oligonucleotide Primers for the Detection of Brain “Cyst” DNA of Experimentally Infected Nude Mice by the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). J. Parasitol. 1996, 82, 272–279.

- Ellis, J.T.; McMillan, D.; Ryce, C.; Payne, S.; Atkinson, R.; Harper, P.A. Development of a Single Tube Nested Polymerase Chain Reaction Assay for the Detection of Neospora caninum DNA. Int. J. Parasitol. 1999, 29, 1589–1596.

- Hughes, J.M.; Williams, R.H.; Morley, E.K.; Cook, D.A.N.; Terry, R.S.; Murphy, R.G.; Smith, J.E.; Hide, G. The Prevalence of Neospora caninum and Co-Infection with Toxoplasma gondii by PCR Analysis in Naturally Occurring Mammal Populations. Parasitology 2006, 132, 29–36.

- Tamponi, C.; Varcasia, A.; Pipia, P.; Zidda, A.; Panzalis, R.; Dore, F.; Dessì, G.; Sanna, G.; Salis, F.; Björkman, C.; et al. ISCOM ELISA in Milk as Screening for Neospora caninum in Dairy Sheep. Large Anim. Rev. 2015, 21, 213–216.

- Huertas-López, A.; Martínez-Carrasco, C.; Cerón, J.J.; Sánchez-Sánchez, R.; Vázquez-Calvo, Á.; Álvarez-García, G.; Martínez-Subiela, S. A Time-Resolved Fluorescence Immunoassay for the Detection of Anti- Neospora caninum Antibodies in Sheep. Vet. Parasitol. 2019, 276, 108994.

- Rossi, G.F.; Cabral, D.D.; Ribeiro, D.P.; Pajuaba, A.C.A.M.; Corrêa, R.R.; Moreira, R.Q.; Mineo, T.W.P.; Mineo, J.R.; Silva, D.A.O. Evaluation of Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum Infections in Sheep from Uberlândia, Minas Gerais State, Brazil, by Different Serological Methods. Vet. Parasitol. 2011, 175, 252–259.

- Vajdi Hokmabad, R.; Khanmohammadi, M.; Sarabim, M. Seroprevalence of Neospora caninum in Miyaneh Sheep (Azerbayejan-E-Shargi Province) by Competitive ELISA and IFAT. Methods 2014, 7, 59–66.

- Björkman, C.; Uggla, A. Serological Diagnosis of Neospora caninum Infection. Int. J. Parasitol. 1999, 29, 1497–1507.

- Pinheiro, A.F.; Borsuk, S.; Berne, M.E.A.; da Silva Pinto, L.; Andreotti, R.; Roos, T.; Roloff, B.C.; Leite, F.P.L. Use of ELISA Based on NcSRS2 of Neospora caninum Expressed in Pichia Pastoris for Diagnosing Neosporosis in Sheep and Dogs. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2015, 24, 148–154.

- Filho, P.C.G.A.; Oliveira, J.M.B.; Andrade, M.R.; Silva, J.G.; Kim, P.C.P.; Almeida, J.C.; Porto, W.J.N.; Mota, R.A. Incidence and Vertical Transmission Rate of Neospora caninum in Sheep. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 52, 19–22.

- Alvarez-García, G.; García-Culebras, A.; Gutiérrez-Expósito, D.; Navarro-Lozano, V.; Pastor-Fernández, I.; Ortega-Mora, L.M. Serological Diagnosis of Bovine Neosporosis: A Comparative Study of Commercially Available ELISA Tests. Vet. Parasitol. 2013, 198, 85–95.

- Jacobson, R.H. Validation of Serological Assays for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases. Rev. Sci. Tech. 1998, 17, 469–526.

- Wapenaar, W.; Barkema, H.W.; Vanleeuwen, J.A.; McClure, J.T.; O’Handley, R.M.; Kwok, O.C.H.; Thulliez, P.; Dubey, J.P.; Jenkins, M.C. Comparison of Serological Methods for the Diagnosis of Neospora caninum Infection in Cattle. Vet. Parasitol. 2007, 143, 166–173.

- Silva, D.A.O.; Lobato, J.; Mineo, T.W.P.; Mineo, J.R. Evaluation of Serological Tests for the Diagnosis of Neospora caninum Infection in Dogs: Optimization of Cut off Titers and Inhibition Studies of Cross-Reactivity with Toxoplasma gondii. Vet. Parasitol. 2007, 143, 234–244.

- Gondim, L.F.P.; Mineo, J.R.; Schares, G. Importance of Serological Cross-Reactivity among Toxoplasma gondii, Hammondia Spp., Neospora Spp., Sarcocystis Spp. and Besnoitia besnoiti. Parasitology 2017, 144, 851–868.

- Zhang, H.; Lee, E.-G.; Yu, L.; Kawano, S.; Huang, P.; Liao, M.; Kawase, O.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, J.; Fujisaki, K.; et al. Identification of the Cross-Reactive and Species-Specific Antigens between Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii Tachyzoites by a Proteomics Approach. Parasitol. Res. 2011, 109, 899–911.

- Regidor-Cerrillo, J.; García-Lunar, P.; Pastor-Fernández, I.; Álvarez-García, G.; Collantes-Fernández, E.; Gómez-Bautista, M.; Ortega-Mora, L.M. Neospora caninum Tachyzoite Immunome Study Reveals Differences among Three Biologically Different Isolates. Vet. Parasitol. 2015, 212, 92–99.

- Nishikawa, Y.; Claveria, F.G.; Fujisaki, K.; Nagasawa, H. Studies on Serological Cross-Reaction of Neospora caninum with Toxoplasma gondii and Hammondia heydorni. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2002, 64, 161–164.

- Andreotti, R.; de Fátima Cepa Matos, M.; Gonçalves, K.N.; Oshiro, L.M.; da Costa Lima-Junior, M.S.; Paiva, F.; Leite, F.L. Comparison of Indirect ELISA Based on Recombinant Protein NcSRS2 and IFAT for Detection of Neospora caninum Antibodies in Sheep. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2009, 18, 19–22.

- Zhou, M.; Cao, S.; Sevinc, F.; Sevinc, M.; Ceylan, O.; Liu, M.; Wang, G.; Moumouni, P.F.A.; Jirapattharasate, C.; Suzuki, H.; et al. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays Using Recombinant TgSAG2 and NcSAG1 to Detect Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum -Specific Antibodies in Domestic Animals in Turkey. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2017, 78, 1877–1881.

- Novoa, M.B.; Aguirre, N.P.; Ormaechea, N.; Palmero, S.; Rouzic, L.; Valentini, B.S.; Sarli, M.; Orcellet, V.M.; Marengo, R.; Vanzini, V.R.; et al. Validation and Field Evaluation of a Competitive Inhibition ELISA Based on the Recombinant Protein TSAG1 to Detect Anti-Neospora caninum Antibodies in Sheep and Goats. Vet. Parasitol. 2020, 284, 109201.

- Soares, H.S.; Ahid, S.M.M.; Bezerra, A.C.D.S.; Pena, H.F.J.; Dias, R.A.; Gennari, S.M. Prevalence of Anti-Toxoplasma gondii and Anti- Neospora caninum Antibodies in Sheep from Mossoró, Rio Grande Do Norte, Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2009, 160, 211–214.

- Maia, M.O.; Maia, M.O.; de Silva, A.R.S.; Gomes, A.A.D.; de Aguiar, D.M.; Pacheco, R.C.; de Costa, A.J.; Santos-Doni, T.R. dos Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum in Sheep Intended for Human Consumption in the Rondônia State, Western Brazilian Amazon. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 74, 101599.

- Romanelli, P.R.; de Matos, A.M.R.N.; Pinto-Ferreira, F.; Caldart, E.T.; de Carmo, J.L.M.; Santos, N.G.D.; de Silva, N.R.; Loeffler, B.B.; Sanches, J.F.Z.; Francisquini, L.S.; et al. Anti-Toxoplasma gondii and Anti-Neospora caninum Antibodies in Sheep from Paraná State, South Brazil: Prevalence and Associated Factors. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2021, 30, e023220.

- Kyaw, T.; Mokhtar, A.M.; Ong, B.; Hoe, C.H.; Aziz, A.R.; Aklilu, E.; Kamarudin, S. Seroprevalence of Neospora caninum in Sheep and Goats of Gua Musang District in Kelantan, Malaysia. Pertanika J. Trop. Agric. Sci. 2018, 41, 477–483.

- Tirosh-Levy, S.; Savitsky, I.; Blinder, E.; Mazuz, M.L. The Involvement of Protozoan Parasites in Sheep Abortions—A Ten-Year Review of Diagnostic Results. Vet. Parasitol. 2022, 303, 109664.

- Diakoua, A.; Anastasia, D.; Papadopoulos, E.; Elias, P.; Panousis, N.; Nikolaos, P.; Karatzias, C.; Charilaos, K.; Giadinis, N.; Nektarios, G. Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum Seroprevalence in Dairy Sheep and Goats Mixed Stock Farming. Vet. Parasitol. 2013, 198, 387–390.

- Kouam, M.; Cabezón, O.; Nogareda, C.; Almeria, S.; Theodoropoulos, G. Comparative Cross-Sectional Study of Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii: Seroprevalence in Sheep of Greece and North-Eastern Spain. Sustain. Dev. Cult. Tradit. J. Spec. Vol. Honor. Profr. Georg. I. 2019, 1–7.

- Otter, A.; Wilson, B.W.; Scholes, S.F.; Jefrrey, M.; Helmick, B.; Trees, A.J. Results of a Survey to Determine Whether Neospora Is a Significant Cause of Ovine Abortion in England and Wales. Vet. Rec. 1997, 140, 175–177.

- Wang, S.; Li, L.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xie, Q.; Zhang, Z. Seroprevalence and Risk Factors of Neospora caninum Infection among Domestic Sheep in Henan Province, Central China. Parasite 2018, 25, 15.

- Blaizot, S.; Herzog, S.A.; Abrams, S.; Theeten, H.; Litzroth, A.; Hens, N. Sample Size Calculation for Estimating Key Epidemiological Parameters Using Serological Data and Mathematical Modelling. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 51.

- Romanelli, P.R.; de Matos, A.M.R.N.; Pinto-Ferreira, F.; Caldart, E.T.; Mareze, M.; Matos, R.L.N.; Freire, R.L.; Mitsuka-Breganó, R.; Headley, S.A.; Minho, A.P.; et al. Seroepidemiology of Ovine Toxoplasmosis and Neosporosis in Breeding Rams from Rio Grande Do Sul, Brazil. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2020, 67 (Suppl. 2), 208–211.

- Al-Majali, A.; Jawasreh, K.; Talafha, H.A.; Talafha, A. Neosporosis in Sheep and Different Breeds of Goats from Southern Jordan: Prevalence and Risk Factors Analysis. Am. J. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2008, 3, 47–52.

- Faria, E.B.; Cavalcanti, E.F.T.S.F.; Medeiros, E.S.; Pinheiro, J.W.; Azevedo, S.S.; Athayde, A.C.R.; Mota, R.A. Risk Factors Associated with Neospora caninum Seropositivity in Sheep from the State of Alagoas, in the Northeast Region of Brazil. J. Parasitol. 2010, 96, 197–199.

- Paiz, L.M.; da Silva, R.C.; Menozzi, B.D.; Langoni, H. Antibodies to Neospora caninum in Sheep from Slaughterhouses in the State of São Paulo, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2015, 24, 95–100.

- Corbellini, L.G.; Smith, D.R.; Pescador, C.A.; Schmitz, M.; Correa, A.; Steffen, D.J.; Driemeier, D. Herd-Level Risk Factors for Neospora caninum Seroprevalence in Dairy Farms in Southern Brazil. Prev. Vet. Med. 2006, 74, 130–141.

- Dubey, J.P.; Schares, G. Neosporosis in Animals—The Last Five Years. Vet. Parasitol. 2011, 180, 90–108.

- Liu, Z.-K.; Li, J.-Y.; Pan, H. Seroprevalence and Risk Factors of Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum Infections in Small Ruminants in China. Prev. Vet. Med. 2015, 118, 488–492.

- Abo-Shehada, M.N.; Abu-Halaweh, M.M. Flock-Level Seroprevalence of and Risk Factors for Neospora caninum among Sheep and Goats in Northern Jordan. Prev. Vet. Med. 2010, 93, 25–32.