Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Camila Xu and Version 1 by Alireza Fath.

Piezoelectric materials are widely employed in precision motion due to their distinctive advantages such as quick response, high displacement resolution, high stiffness, high actuating force, and little heat generation.

- piezoelectric

- microrobotic systems

- microelectromechanical systems

- sensing

1. Introduction

In recent years, there has been an increasing effort to utilize piezoelectric materials in the development of microrobotic systems. With the growing number of mechanisms that scientists use to develop microrobots, there is a great challenge in designing lighter and more efficient microrobots to achieve a certain level of autonomy. Important reviews on microrobotics have been published with different focuses, such as micro-scale flapping-wing robots [1], biohybrid microrobots [2], light-powered microswimmers [3] and drug delivery microrobots [4], etc.

Piezoelectric materials are widely employed in precision motion due to their distinctive advantages such as quick response, high displacement resolution, high stiffness, high actuating force, and little heat generation [5,6][5][6]. These features make piezoelectric materials good candidates for developing the actuating module of microrobots. In 2006, Anton and Sodano [7] reviewed the literature (2003–2006) on power harvesting using piezoelectric materials for self-powered wireless sensor applications, and they updated their review with Safaei [8] to include the literature from 2008 to 2018. Moreover, Mahapatra et al. [9] reviewed the nanostructures of piezoelectric materials, manufacturing methods, and material-specific underpinning concepts. The application of piezoelectric actuators is discussed more specifically in areas such as medical and robotics engineering by Uchino [10]. In 2018, Shevtsov et al. [11] discussed the mathematical modeling, experimental techniques, and computer algorithms for piezoelectric generators. They included the particular effects of piezoceramics, such as the flexoelectric effect, and methods for defect identification. As piezoelectric materials development advanced, computational methods were proposed to contain certain phenomena, including rate-dependent switching in the micromechanical 3D finite element model [12].

The mechanism by which piezoelectric microrobots achieve mobility, as well as the environment in which they are expected to maneuver, are important in the development of microrobots. Each mechanism has specific characteristics suitable for an objective environment. Ambulatory locomotion gives the advantages of mobility on rough surfaces as opposed to the traditional wheeled mechanism [13]. Moreover, increasing the number of legs enables the system to be more robust due to the actuation failure [14]. The inchworm mechanism can gain control of the friction force by exploiting the squeeze film effect [15,16][15][16]. To create biologically-inspired flapping-wing microrobots like insects for exploration purposes, high-density actuation power [17] is required, which can be developed using piezoelectric materials. Additionally, amphibious microrobots are designed to conform to the multi-environment [18].

The key roles in the operation of the microrobot are the power source to achieve mobility and the way it is transferred to the microrobot. The piezoelectric materials that are used in microrobots require high input voltages, which can reach as high as 220 V [19], creating challenges for power transmission. As a promising strategy, there are a variety of methods based on energy harvesting in the direction of the wireless functionality of microrobots relying on piezoelectric actuation [20].

The sensing capabilities involve microrobots or piezo-based devices dealing with their environments to achieve autonomy like their biological counterparts, such as tactile sensing similar to that of nature-inspired insects [21]. Additionally, piezoelectric sensing is investigated in a range of fields such as detecting cracks [22] and human health monitoring [23], which could be used to inspire ideas for microrobotic applications.

The control strategy is essential for the microrobots to achieve stability and follow trajectories. Due to their lightweight and miniature sizes, microrobots are more sensitive to environmental disturbances. Researchers have attempted to address these challenges by adding dampers [24], taking into account the disturbances [25], and using adaptive, model-free MIMO, nonlinear, and spiking neural network control strategies [26,27,28,29,30][26][27][28][29][30]. Moreover, the augmentation of accurate sensors to the system helps enhance the stability control of the microrobot.

As for the piezoelectric sensors in microrobots, Fahlbusch and Fatikow [73][31] gave a preliminary overview of force sensing during manipulation in microrobotic systems. Tactile sensors inspired by insects such as spiders and geckos have been investigated by Koç and Akça [21]. In 2014, Lee et al. [74][32] fabricated a piezoelectric thin-film force sensor that can be used in biomedical applications. Adam et al. [75][33] developed a microrobot for various environments that has a micro-force sensing magnet. As it is challenging to develop a highly integrated sensing system for microrobots, Jayaram et al. [76][34] proposed a method to determine the velocity as a function of frequency and voltage in piezoelectric materials. Moreover, proprioceptive sensing in locomotion movement is presented by Doshi et al. [77][35]. In 2019, Chopra and Gravish [78][36] used the linear relationship of actuator displacement and voltages with an input of 25 V to 200 V to detect wing collision for flying robots. Furthermore, as vision is an important sensing ability in the environment for insect-sized microrobots, Iyer et al. [79][37] used a wireless steerable vision on a live beetle that is capable of streaming via Bluetooth radio. Moreover, Han et al. [80][38] reviewed triboelectric and piezoelectric sensors for displacement, pressure, and acceleration.

Various methods have been used to design piezoelectric sensors. Yamashita et al. [81][39] developed ultrasonic micro-sensors with PZT thin films and adjusted their resonance frequencies. Chen and Li [82][40] proposed a PZT-based self-sensing actuator capable of not only generating high-resolution displacement but also monitoring the dynamic characteristics of the mechatronic system. Self-powered piezoelectric materials are studied as both sensors and power generators [83][41]. In addition, micro-grippers that use micro-force sensors with cantilever structures using piezoelectric biomorphs were investigated [84][42]. A piezoelectric wireless micro-sensing accelerometer has been studied [85][43]. In 2017, Hosseini and Yousefi [86][44] examined the PVDF fabric with the control of crystalline phases for use in flexible force sensors. Hu et al. [87][45] enhanced piezoelectric sensing by using penetrated electrodes and nanoparticles. Cao et al. [88][46] used FENG to develop the self-powered bending sensors.

Moreover, piezoelectric materials can serve as integrated sensors for the structures of robotic systems, such as observing and detecting fatigue cracks [22], as well as identifying structural damage [89][47]. Moreover, piezoelectric materials have been used as a means of monitoring structural strength [90,91][48][49]. In 2010, Feng and Tsai [92][50] developed a new piezoelectric acoustic emission sensor with PVDF that has a wider bandwidth, and in 2020, Jiao et al. [93][51] gave a review on structure monitoring with piezoelectric sensing.

As for the piezoelectric sensors in microrobots, Fahlbusch and Fatikow [73][31] gave a preliminary overview of force sensing during manipulation in microrobotic systems. Tactile sensors inspired by insects such as spiders and geckos have been investigated by Koç and Akça [21]. In 2014, Lee et al. [74][32] fabricated a piezoelectric thin-film force sensor that can be used in biomedical applications. Adam et al. [75][33] developed a microrobot for various environments that has a micro-force sensing magnet. As it is challenging to develop a highly integrated sensing system for microrobots, Jayaram et al. [76][34] proposed a method to determine the velocity as a function of frequency and voltage in piezoelectric materials. Moreover, proprioceptive sensing in locomotion movement is presented by Doshi et al. [77][35]. In 2019, Chopra and Gravish [78][36] used the linear relationship of actuator displacement and voltages with an input of 25 V to 200 V to detect wing collision for flying robots. Furthermore, as vision is an important sensing ability in the environment for insect-sized microrobots, Iyer et al. [79][37] used a wireless steerable vision on a live beetle that is capable of streaming via Bluetooth radio. Moreover, Han et al. [80][38] reviewed triboelectric and piezoelectric sensors for displacement, pressure, and acceleration.

Various methods have been used to design piezoelectric sensors. Yamashita et al. [81][39] developed ultrasonic micro-sensors with PZT thin films and adjusted their resonance frequencies. Chen and Li [82][40] proposed a PZT-based self-sensing actuator capable of not only generating high-resolution displacement but also monitoring the dynamic characteristics of the mechatronic system. Self-powered piezoelectric materials are studied as both sensors and power generators [83][41]. In addition, micro-grippers that use micro-force sensors with cantilever structures using piezoelectric biomorphs were investigated [84][42]. A piezoelectric wireless micro-sensing accelerometer has been studied [85][43]. In 2017, Hosseini and Yousefi [86][44] examined the PVDF fabric with the control of crystalline phases for use in flexible force sensors. Hu et al. [87][45] enhanced piezoelectric sensing by using penetrated electrodes and nanoparticles. Cao et al. [88][46] used FENG to develop the self-powered bending sensors.

Moreover, piezoelectric materials can serve as integrated sensors for the structures of robotic systems, such as observing and detecting fatigue cracks [22], as well as identifying structural damage [89][47]. Moreover, piezoelectric materials have been used as a means of monitoring structural strength [90,91][48][49]. In 2010, Feng and Tsai [92][50] developed a new piezoelectric acoustic emission sensor with PVDF that has a wider bandwidth, and in 2020, Jiao et al. [93][51] gave a review on structure monitoring with piezoelectric sensing.

2. Sensing Capabilities

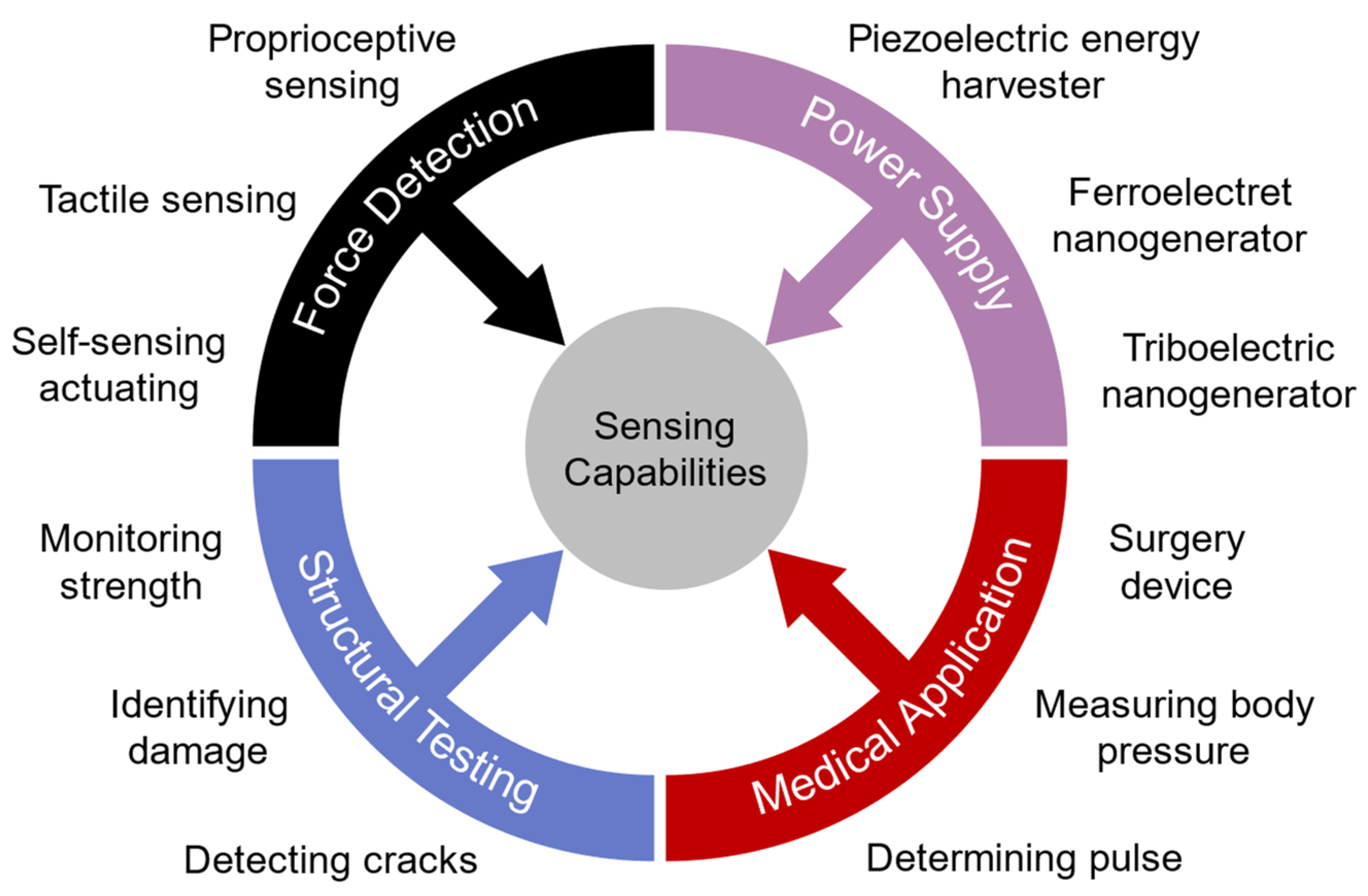

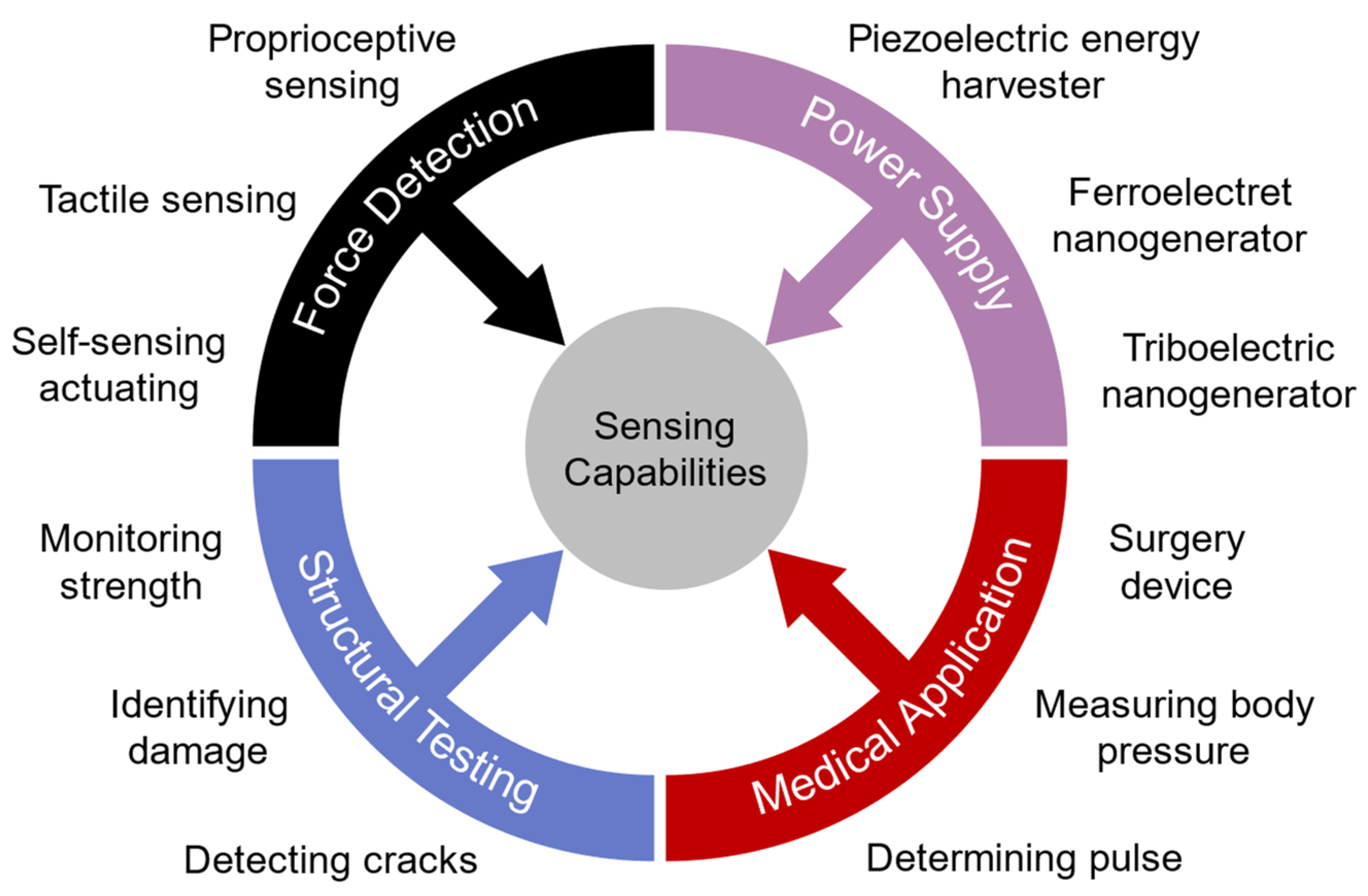

As the research interest in microrobotics grows, more sensing capabilities are needed to enable insect-like autonomous robots. Figure 1 illustrates the classifications of sensing capabilities for microrobotic applications.

Figure 1.

Categories of piezoelectric sensing applications that can be used in microrobots.

References

- Farrell Helbling, E.; Wood, R.J. A review of propulsion, power, and control architectures for insect-scale flapping-wing vehicles. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2018, 70, 010801.

- Alapan, Y.; Yasa, O.; Yigit, B.; Yasa, I.C.; Erkoc, P.; Sitti, M. Microrobotics and microorganisms: Biohybrid autonomous cellular robots. Annu. Rev. Control Rob. Auton. Syst. 2019, 2, 205–230.

- Bunea, A.I.; Martella, D.; Nocentini, S.; Parmeggiani, C.; Taboryski, R.; Wiersma, D.S. Light—Powered Microrobots: Challenges and Opportunities for Hard and Soft Responsive Microswimmers. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2021, 3, 2000256.

- Jang, D.; Jeong, J.; Song, H.; Chung, S.K. Targeted drug delivery technology using untethered microrobots: A review. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2019, 29, 053002.

- Li, W.; Chen, X. Compensation of hysteresis in piezoelectric actuators without dynamics modeling. Sens. Actuators A 2013, 199, 89–97.

- Li, W.; Chen, X.; Li, Z. Inverse compensation for hysteresis in piezoelectric actuator using an asymmetric rate-dependent model. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2013, 84, 115003.

- Anton, S.R.; Sodano, H.A. A review of power harvesting using piezoelectric materials (2003–2006). Smart Mater. Struct. 2007, 16, R1–R21.

- Safaei, M.; Sodano, H.A.; Anton, S.R. A review of energy harvesting using piezoelectric materials: State-of-the-art a decade later (2008–2018). Smart Mater. Struct. 2019, 28, 113001.

- Mahapatra, S.D.; Mohapatra, P.C.; Aria, A.I.; Christie, G.; Mishra, Y.K.; Hofmann, S.; Thakur, V.K. Piezoelectric Materials for Energy Harvesting and Sensing Applications: Roadmap for Future Smart Materials. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2100864.

- Uchino, K. Piezoelectric actuators 2006. J. Electroceram. 2008, 20, 301–311.

- Shevtsov, S.N.; Soloviev, A.N.; Parinov, I.A.; Cherpakov, A.V.; Chebanenko, V.A. Piezoelectric Actuators and Generators for Energy Harvesting: Research and Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; p. 182.

- Arockiarajan, A.; Menzel, A.; Delibas, B.; Seemann, W. Computational modeling of rate-dependent domain switching in piezoelectric materials. Eur. J. Mech. -A/Solids 2006, 25, 950–964.

- Sahai, R.; Avadhanula, S.; Groff, R.; Steltz, E.; Wood, R.; Fearing, R.S. Towards a 3g crawling robot through the integration of microrobot technologies. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Orlando, FL, USA, 15–19 May 2006; pp. 296–302.

- Hoffman, K.L.; Wood, R.J. Robustness of centipede-inspired millirobot locomotion to leg failures. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Tokyo, Japan, 3–7 November 2013; pp. 1472–1479.

- Itatsu, Y.; Torii, A.; Ueda, A. Inchworm type microrobot using friction force control mechanisms. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Symposium on Micro-NanoMechatronics and Human Science, Nagoya, Japan, 6–9 November 2011; pp. 273–278.

- Schindler, C.B.; Gomez, H.C.; Acker-James, D.; Teal, D.; Li, W.; Pister, K.S. 15 millinewton force, 1 millimeter displacement, low-power MEMS gripper. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 33rd International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 January 2020; pp. 485–488.

- Ma, K.Y.; Chirarattananon, P.; Fuller, S.B.; Wood, R.J. Controlled flight of a biologically inspired, insect-scale robot. Science 2013, 340, 603–607.

- Becker, F.; Zimmermann, K.; Volkova, T.; Minchenya, V.T. An amphibious vibration-driven microrobot with a piezoelectric actuator. Regul. Chaotic Dyn. 2013, 18, 63–74.

- Karpelson, M.; Wei, G.-Y.; Wood, R.J. A review of actuation and power electronics options for flapping-wing robotic insects. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Pasadena, CA, USA, 19–23 May 2008; pp. 779–786.

- Kim, H.S.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, J. A review of piezoelectric energy harvesting based on vibration. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2011, 12, 1129–1141.

- Koç, İ.M.; Akça, E. Design of a piezoelectric based tactile sensor with bio-inspired micro/nano-pillars. Tribol. Int. 2013, 59, 321–331.

- Ihn, J.-B.; Chang, F.-K. Detection and monitoring of hidden fatigue crack growth using a built-in piezoelectric sensor/actuator network: I. Diagnostics. Smart Mater. Struct. 2004, 13, 609.

- Sun, R.; Carreira, S.C.; Chen, Y.; Xiang, C.; Xu, L.; Zhang, B.; Chen, M.; Farrow, I.; Scarpa, F.; Rossiter, J. Stretchable piezoelectric sensing systems for self-powered and wireless health monitoring. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2019, 4, 1900100.

- Teoh, Z.E.; Fuller, S.B.; Chirarattananon, P.; Prez-Arancibia, N.; Greenberg, J.D.; Wood, R.J. A hovering flapping-wing microrobot with altitude control and passive upright stability. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Vilamoura-Algarve, Portugal, 7–12 October 2012; pp. 3209–3216.

- Chirarattananon, P.; Chen, Y.; Helbling, E.F.; Ma, K.Y.; Cheng, R.; Wood, R.J. Dynamics and flight control of a flapping-wing robotic insect in the presence of wind gusts. Interface Focus 2017, 7, 20160080.

- Pérez-Arancibia, N.O.; Whitney, J.P.; Wood, R.J. Lift force control of flapping-wing microrobots using adaptive feedforward schemes. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2011, 18, 155–168.

- Chirarattananon, P.; Ma, K.Y.; Wood, R.J. Adaptive control of a millimeter-scale flapping-wing robot. Bioinspir. Biomim. 2014, 9, 025004.

- Pérez-Arancibia, N.O.; Duhamel, P.-E.J.; Ma, K.Y.; Wood, R.J. Model-free control of a hovering flapping-wing microrobot. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2015, 77, 95–111.

- Clawson, T.S.; Ferrari, S.; Fuller, S.B.; Wood, R.J. Spiking neural network (SNN) control of a flapping insect-scale robot. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 55th Conference on Decision and Control (CDC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 12–14 December 2016; pp. 3381–3388.

- Chirarattananon, P.; Ma, K.Y.; Wood, R.J. Single-loop control and trajectory following of a flapping-wing microrobot. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Hong Kong, China, 31 May–5 June 2014; pp. 37–44.

- Fahlbusch, S.; Fatikow, S. Force sensing in microrobotic systems-an overview. In Proceedings of the 1998 IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Circuits and Systems. Surfing the Waves of Science and Technology (Cat. No. 98EX196), Lisboa, Portugal, 7–10 September 1998; pp. 259–262.

- Lee, J.; Choi, W.; Yoo, Y.K.; Hwang, K.S.; Lee, S.-M.; Kang, S.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.H. A micro-fabricated force sensor using an all thin film piezoelectric active sensor. Sensors 2014, 14, 22199–22207.

- Adam, G.; Chowdhury, S.; Guix, M.; Johnson, B.V.; Bi, C.; Cappelleri, D. Towards functional mobile microrobotic systems. Robotics 2019, 8, 69.

- Jayaram, K.; Jafferis, N.T.; Doshi, N.; Goldberg, B.; Wood, R.J. Concomitant sensing and actuation for piezoelectric microrobots. Smart Mater. Struct. 2018, 27, 065028.

- Doshi, N.; Jayaram, K.; Castellanos, S.; Kuindersma, S.; Wood, R.J. Effective locomotion at multiple stride frequencies using proprioceptive feedback on a legged microrobot. Bioinspiration Biomim. 2019, 14, 056001.

- Chopra, S.; Gravish, N. Piezoelectric actuators with on-board sensing for micro-robotic applications. Smart Mater. Struct. 2019, 28, 115036.

- Iyer, V.; Najafi, A.; James, J.; Fuller, S.; Gollakota, S. Wireless steerable vision for live insects and insect-scale robots. Sci. Rob. 2020, 5, eabb0839.

- Han, Z.; Jiao, P.; Zhu, Z. Combination of piezoelectric and triboelectric devices for robotic self-powered sensors. Micromachines 2021, 12, 813.

- Yamashita, K.; Chansomphou, L.; Murakami, H.; Okuyama, M. Ultrasonic micro array sensors using piezoelectric thin films and resonant frequency tuning. Sens. Actuators A 2004, 114, 147–153.

- Chen, X.; Li, W. A monolithic self-sensing precision stage: Design, modeling, calibration, and hysteresis compensation. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2014, 20, 812–823.

- Ng, T.; Liao, W. Sensitivity analysis and energy harvesting for a self-powered piezoelectric sensor. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2005, 16, 785–797.

- Huang, X.; Cai, J.; Wang, M.; Lv, X. A piezoelectric bimorph micro-gripper with micro-force sensing. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE International Conference on Information Acquisition, Hong Kong, China, 27 June 2005–3 July 2005; p. 5.

- Shen, Z.; Tan, C.Y.; Yao, K.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.F. A miniaturized wireless accelerometer with micromachined piezoelectric sensing element. Sens. Actuators A 2016, 241, 113–119.

- Hosseini, S.M.; Yousefi, A.A. Piezoelectric sensor based on electrospun PVDF-MWCNT-Cloisite 30B hybrid nanocomposites. Org. Electron. 2017, 50, 121–129.

- Hu, X.; Yan, X.; Gong, L.; Wang, F.; Xu, Y.; Feng, L.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, Y. Improved piezoelectric sensing performance of P (VDF–TrFE) nanofibers by utilizing BTO nanoparticles and penetrated electrodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 7379–7386.

- Cao, Y.; Li, W.; Sepulveda, N. Performance of Self-Powered, Water-Resistant Bending Sensor Using Transverse Piezoelectric Effect of Polypropylene Ferroelectret Polymer. IEEE Sens. J. 2019, 19, 10327–10335.

- Xu, D.; Cheng, X.; Huang, S.; Jiang, M. Identifying technology for structural damage based on the impedance analysis of piezoelectric sensor. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 2522–2527.

- Shin, S.W.; Qureshi, A.R.; Lee, J.-Y.; Yun, C.B. Piezoelectric sensor based nondestructive active monitoring of strength gain in concrete. Smart Mater. Struct. 2008, 17, 055002.

- Chen, J.; Li, P.; Song, G.; Ren, Z. Piezo-based wireless sensor network for early-age concrete strength monitoring. Optik 2016, 127, 2983–2987.

- Feng, G.-H.; Tsai, M.-Y. Acoustic emission sensor with structure-enhanced sensing mechanism based on micro-embossed piezoelectric polymer. Sens. Actuators A 2010, 162, 100–106.

- Jiao, P.; Egbe, K.-J.I.; Xie, Y.; Matin Nazar, A.; Alavi, A.H. Piezoelectric sensing techniques in structural health monitoring: A state-of-the-art review. Sensors 2020, 20, 3730.

More