Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Dean Liu and Version 1 by John David Heiss.

Medulloblastoma is the most common pediatric brain tumor, comprising one-third of all pediatric brain tumors, and originating in the posterior fossa of the brain. The disease is categorized into four subtypes: WNT, Sonic hedgehog (SHH), Group 3, and Group 4. Each subtype has unique pathogenesis, biomarkers, prognosis, response to therapy, and potential for further pharmacologic investigation.

- pediatric brain tumors

- medulloblastoma

- molecular subtype

1. Introduction

Medulloblastoma is a central nervous system (CNS) tumor of cerebellar origin that comprises approximately 1% of all brain tumors [1,2][1][2]. However, medulloblastoma is the most common malignant brain cancer in children, accounting for 25–30% of childhood brain tumors and over 40% of posterior fossa childhood tumors [3]. Thus, medulloblastoma is primarily a childhood cancer, with an annual incidence of 300–350 new cases in the United States [4]. Most patients present before 16 years of age, with over 70% before 10, a third of which are younger than 3 years old; very few cases present under 1 year old [5,6][5][6]. The median age of diagnosis in children is about 5–7 years [7]. This age distribution highlights the current understanding of these tumors as remnants of aberrant embryonic cerebellar cells [8].

2. Characteristic and Presentation

Medulloblastoma typically arises within the posterior fossa in the cerebellum or its junction with the brainstem [13][9]. Recent studies have provided great insight into how the developmental biology of these tumors predicts their clinical behavior. For example, a recent lineage tracing study of the SHH subtype of medulloblastoma demonstrated that these tumors arise during the post-natal period from aberrantly persistent undifferentiated neural crest cells within the transient external germinal layer, which forms by embryonic migration of another transient structure, the rhombic lip. These cells ultimately become mature granule neurons within the internal granular cell layer of the cerebellum after the first year of life. These cells may not complete migration—establishing themselves anywhere along a path from the rhombic lip, which forms a critical interface between the cerebellum and brainstem in the embryo—into their proper position within the cerebellum. The tumor location critically affects the clinical course of these tumors in early childhood. A relationship between molecular pathogenesis, tumor location, and clinical behavior is seen not only in the SHH medulloblastoma subtype but also in the other medulloblastoma subtypes [14][10]. Typically, medulloblastoma arises within the medulla and expands the cerebellum to obstruct the fourth ventricle, creating signs of increased intracranial pressure such as major morning headaches, nausea, vomiting, and altered mental status. Compression of the adjacent brainstem structures and exiting cranial nerves may produce focal neurological deficits. For example, tumors within the cerebellar vermis and hemispheres cause gait ataxia and focal limb incoordination, respectively [15][11]. If left unchecked, tumor cells may disseminate through the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to the spinal canal. In rare instances, medulloblastoma may metastasize systemically to bone and bone marrow [16,17][12][13]. Tumors confined to the cerebellum have different symptoms than those metastasizing through the CSF and bloodstream.3. Diagnosis

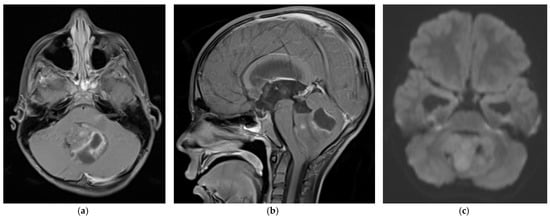

Medulloblastoma should be suspected clinically in children presenting with signs and symptoms of a posterior fossa mass, such as those listed above. Diagnosis requires brain imaging. The most accurate imaging modality is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Medulloblastoma typically appears hypointense and hyperintense relative to grey matter on T1- and T2-weighted MRI, respectively. Intravenous contrast injection produces contrast enhancement throughout the tumor on MRI or CT [18][14]. The location of the tumor on imaging reflects the developmental pathogenesis described above. The mass usually originates in the inferior vermis, and enlarges to compress the fourth ventricle. Depending on the molecular subgroup, the tumor may involve the cerebellar hemispheres, the cerebellopontine angle, or it may mimic meningioma by originating in the tentorium [19,20][15][16]. Medulloblastoma may spread to the spinal canal, forming leptomeningeal “drop metastasis” on the nerve roots of the cauda equina. Medulloblastoma may also originate in extra-axial locations [21,22,23,24][17][18][19][20]. The various molecular and histopathological subtypes of medulloblastoma have distinguishing MRI features (Figure 1) [25][21]. Diffusion-weighted imaging is characteristic of medulloblastoma compared to other posterior fossa tumors [26,27][22][23]. While radiographic imaging can hone in on the correct diagnosis, confirmation of medulloblastoma is made on hematoxylin and eosin staining of histopathologic specimens obtained during surgical resection, which is part of the standard treatment regimen as outlined below. Molecular techniques further subtype the medulloblastoma [9][24]. Surgical resection improves prognosis, although near-total resection (NTR) does not increase recurrent risk compared to gross total resection (GTR). It is not recommended to achieve GTR over NTR at the cost of neurologic deficits [3,28][3][25].

Figure 1. 5 year old boy with non-SHH/WNT medulloblastoma. Axial (a) and sagittal (b) T1-weighted MRI scans after intravenous contrast demonstrate a mass with cystic and solid components that enhances and extends into the fourth ventricle. The axial diffusion-weighted image (DWI) (c) shows restricted diffusion (higher signal intensity) within the tumor. The temporal horns of the lateral ventricles are distended, signifying obstructive hydrocephalus.

4. World Health Organization Classification and Grade

As discussed above, a panel of experts agreed at a conference held in Boston in 2010 to use molecular profiling to subdivide medulloblastoma into four different subtypes (WNT, SHH, Group 3, and Group 4) [13][9]. The molecular subtyping was separate from the 2016 WHO classification of medulloblastoma into four histologic subtypes: classic, desmoplastic/nodule, large cell/anaplastic, and medulloblastoma with extensive nodularity (MBEN). Most large cell/anaplastic medulloblastoma tumors belong to the SHH, Group 3, and Group 4 molecular subtypes, while the classic morphology was more typical of WNT tumors. Some SHH subtype tumors have desmoplastic/nodular morphology [29,30][26][27]. The updated 2021 World Health Organization (WHO) central nervous system tumor classification combined the four histologic subtypes into a single type, “Medulloblastoma, histologically defined.” The 2021 WHO classification further elaborated the medulloblastoma molecular subtypes: the SHH subgroup was divided into four groups, and the Group 3 and 4 subtypes (non-SHH, non-WNT) into eight groups [10][28]. These separations enabled more precise therapeutic targeting of the different medulloblastoma subtypes by conventional therapies and experimental therapies like gene therapy. As described below, each subtype group was defined by tumor genotyping, immunohistochemistry, and an individual prognosis.5. Molecular Subtyping

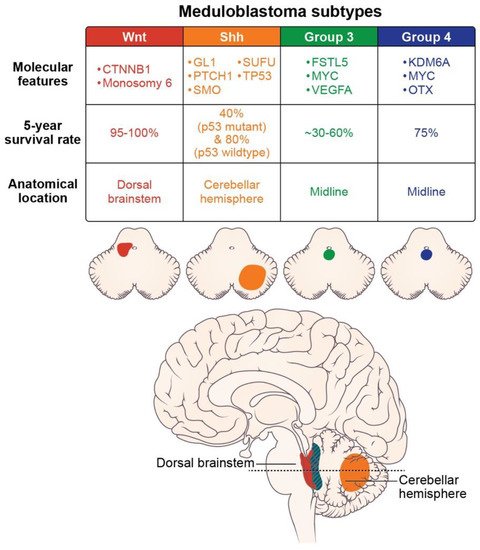

Molecular subtypes of medulloblastoma are characterized by unique molecular features and anatomic features, as described in Figure 2. Subgroup-specific treatments are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Clinical trials and therapies in development for the four pediatric medulloblastoma subtypes.

| WNT Subtype | ||

| Clinical trial: Reducing doses of craniospinal radiation and chemotherapy | NCT01878617: A Clinical and Molecular Risk-Directed Therapy for Newly Diagnosed Medulloblastoma | |

| NCT02066220: International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) PNET 5 Medulloblastoma | ||

| NCT02724579: Reduced Craniospinal Radiation Therapy and Chemotherapy in Treating Younger Patients with Newly Diagnosed WNT-Driven Medulloblastoma | ||

| Proposed therapy: WNT antagonists | Phoenix, et al. (2016) [31] reported that WNT antagonists block the formation of a blood-brain barrier, and thereby promote chemotherapy penetration and high intratumoral drug concentrations. | Phoenix, et al. (2016) [29] reported that WNT antagonists block the formation of a blood-brain barrier, and thereby promote chemotherapy penetration and high intratumoral drug concentrations. |

| SHH Subtype | ||

| Proposed therapy: nanoparticles | Valcourt, et al. (2020) [32] and Caimano, et al. (2021) [33] reported their development of nanoparticles that encapsulate SMO or GLI inhibitors to improve drug delivery to this tumor subtype. | Valcourt, et al. (2020) [30] and Caimano, et al. (2021) [31] reported their development of nanoparticles that encapsulate SMO or GLI inhibitors to improve drug delivery to this tumor subtype. |

| Group 3 Subtype | ||

| Proposed therapy: Ribavirin | Huq, et al. (2021) [34] reported therapeutic potential for ribavirin to reduce medulloblastoma cell growth and prolong survival. | Huq, et al. (2021) [32] reported therapeutic potential for ribavirin to reduce medulloblastoma cell growth and prolong survival. |

| Proposed therapy: Anti-vascularization therapy | Thompson, et al. (2017) [35] reported increased vascularity in Group 3 tumors and proposed using anti-VEGFA anti-vascularization therapy to inhibit tumor growth. | Thompson, et al. (2017) [33] reported increased vascularity in Group 3 tumors and proposed using anti-VEGFA anti-vascularization therapy to inhibit tumor growth. |

| Group 4 Subtype | ||

| Proposed therapy: anti-ERBB4-SRC receptor tyrosine kinase | Forget, et al. (2018) [36] demonstrated that the combination of TP53 inactivation and aberrant signaling of the ERBB4-SRC receptor tyrosine may induce Group 4-like tumor growth. They suggested molecular therapies to inhibit these effects. | Forget, et al. (2018) [34] demonstrated that the combination of TP53 inactivation and aberrant signaling of the ERBB4-SRC receptor tyrosine may induce Group 4-like tumor growth. They suggested molecular therapies to inhibit these effects. |

5.1. WNT

The WNT-pathway-derived subtype comprises 10% of medulloblastoma cases, and generally affects children over four years of age [13][9]. These tumors arise in the cerebellar midline and may spread to the dorsal brainstem [37][35]. They have the best prognosis of the four subtypes, with nearly 100% 5-year survival and rare metastasis [30,38,39,40][27][36][37][38]. Most WNT-derived tumors have a somatic CTNNB1 mutation, encoding B-catenin, and chromosomal variations like monosomy 6 [41,42][39][40]. Due to its favorable prognosis and low-risk biological profile, several clinical trials are investigating de-escalating treatment methods. Clinical trials NCT01878617, NCT02066220, and NCT02724579, examining reduced doses of craniospinal radiation and chemotherapy, are expected to report their results within the next few years [14][10]. Recent studies have found that WNT medulloblastoma secretes WNT antagonists that prevent blood-brain barrier formation. This aberrant tumor vessel phenotype permits chemotherapy to reach and achieve high concentration within the WNT-subtype tumor, contributing to its excellent prognosis [31][29]. Unlike the SHH subtype, recurrence of WNT subtype medulloblastoma is not associated with the extent of resection and metastatic disease [28,43,44][25][41][42]. Anatomically, most relapses occur in the lateral ventricles; the remainder occur in the leptomeninges and surgical tumor bed or, in rare cases, in the suprasellar region [45,46][43][44].5.2. SHH

The SHH subtype is the most common medulloblastoma subtype, with an estimated 25–30% prevalence. The SHH subtype usually occurs in children less than 5 years old [38,47][36][45]. The tumors arise in the cerebellar hemispheres, and are characterized by mutated or inactivating mutations of PTCH1 (43%) and SUFU (10%) [37][35]. This subtype has an 80% overall survival in large cohort trials [39,48][37][46]. A multicenter phase 2 trial from St. Jude’s (SJYC07; NCT00602667) divided the SHH subtype into two molecular subgroups: iSHH-I and iSHH-II, based on their distinct methylation patterns. In patients under 5 years of age not receiving radiation, intraventricular chemotherapy, or high-dose chemotherapy, the iSHH-II group had improved progression-free survival compared to iSHH-I [49][47]. The prognosis of SHH subtype medulloblastoma further depends on TP53 gene status, the most critical risk factor for SHH medulloblastoma. While SHH is generally distributed in young children, SHH/TP53 mutant tumors occur almost exclusively in children older than 5 years, of whom 56% carry a TP53 germline mutation. The TP53 mutation confers a relatively poor prognosis, with a 41% five-year overall survival rate, compared to 81% in the SHH subtype without the TP53 mutation. This mutation is responsible for 72% of deaths in children with the SHH subtype [50][48]. Relapse of the SHH subtype medulloblastoma generally occurs in the surgical tumor bed [51][49]. The SHH pathway’s two main molecular targets are Smoothened (SMO) receptor antagonists and GL1 transcription factor inhibitors [52][50]. Small and large molecules cannot cross the blood-brain barrier of this subtype, making it resistant to chemotherapy, unlike WNT subtype tumors. The development of nanoparticles, which may encapsulate SMO or GLI inhibitors, may improve drug delivery [32,33][30][31]. Nanoparticle technology provides a promising new research avenue for treating SHH subtype medulloblastoma, based on testing in in vitro and in vivo medulloblastoma models.5.3. Group 3

Group 3 comprises approximately one-quarter of medulloblastoma cases, affecting infants and young children. Males predominate 2:1 to females in Group 3 [53][51]. Group 3 is an aggressive medulloblastoma subtype, with over 40% of patients having metastases at diagnosis. The five-year survival rate ranges between 30% and 60% [12,14,54][10][52][53]. Like WNT-type tumors, Group 3 tumors grow in the midline and often into the fourth ventricle. The Group 3 subtype tumor recurs almost exclusively in the leptomeninges [51][49]. No therapeutic agents effectively target Group 3 medulloblastoma or reduce its high mortality. A better understanding of its underlying tumor molecular genetics and molecular pathways will provide drug targets that can overcome its therapeutic resistance. Genotyping and transcriptomics combined with methylation have successfully identified many biomarkers that may direct future therapies. About 20% of Group 3 tumors have MYC oncogene amplification, which carries a poor prognosis [55][54]. Transcriptome and tissue studies have also identified follistatin-like 5 (FSTL5) immunopositivity as a poor prognostic factor in Group 3 and Group 4 tumors [56][55]. Other molecular identifiers in Group 3 include increased expression of GFI, IMPG2, GABRA5, EGFL11, NRL, MAB21 L2 [57[56][57],58], and MYC-driven long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs). These genes driving Group 3 medulloblastoma are being targeted in preclinical animal models [57][56]. Group 3 tumor growth depends on angiogenesis, as evidenced by the significant elevation of VEGFA mRNA expression in this group compared to other medulloblastoma subtypes. Grade 3 tumor vascularity is also associated with overexpression of the RNH1, SCG2, and AGGF1 genes, and with lower survival rates. Anti-vascularization therapies used in glioblastoma clinical trials may be repurposed for Group 3 medulloblastoma [35][33]. Ribavirin— antiviral medication for RSV and hepatitis C infections—may have therapeutic potential. Ribavirin significantly prolonged survival and reduced medulloblastoma cell growth in a mouse model of Group 3 medulloblastoma [34][32]. ABC transporters are implicated in the resistance of medulloblastoma cells to radiation and chemotherapy treatment. In Group 3 subtype mouse models, the ABCG2 transporter is overexpressed. Inhibiting this transporter in in vivo studies enhanced the antiproliferative response to topotecan chemotherapy [59][58]. ABCA8 and ABCB4 family transporters are highly expressed in the SHH pathway-driven tumors, and confer resistance to radiation therapy [60][59].5.4. Group 4

The Group 4 subtype comprises approximately 35% of medulloblastoma, and occurs in children of all ages (median age, 9 years). There is a 3:1 predominance of males to females in this group. Group 4 medulloblastoma is the least understood medulloblastoma subtype. The Group 4 and 3 subtypes share many features. Like the Group 3 subtype, Group 4 medulloblastoma occurs in the midline vermis, and an underlying molecular pathway does not yet explain its pathogenesis. However, the two non-WNT, non-SHH medulloblastoma subtypes have MYC and OTX2 amplifications [42][40]. About 6–9% of Group 4 tumors are associated with molecular targets (KDM6A, ZMYM3, KTM2C, and KBTBD4) [14][10]. In preclinical mouse models, aberrant signaling of ERBB4-SRC receptor tyrosine kinase and TP53 inactivation may induce a tumor resembling Group 4 medulloblastoma [36][34]. These findings support exploring tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as dasatinib as potential therapeutic agents. The estimated five-year overall survival rate of Group 4 medulloblastoma is 75%. Survival is reduced by metastasis [61][60]. Low-risk and standard-risk disease is characterized by a loss of chromosome 11 and a lack of metastasis. High-risk disease is defined by metastasis at the time of diagnosis. Interestingly, an ‘intermediate’ type of medulloblastoma, with transitional features of Group 3 and Group 4, has a better prognosis than Group 3 or 4 alone [62][61].References

- Pan, E. Adult Medulloblastomas. In Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine, 6th ed.; NCBI: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2003.

- Hovestadt, V.; Smith, K.S.; Bihannic, L.; Filbin, M.G.; Shaw, M.L.; Baumgartner, A.; DeWitt, J.C.; Groves, A.; Mayr, L.; Weisman, H.R.; et al. Resolving medulloblastoma cellular architecture by single-cell genomics. Nature 2019, 572, 74–79.

- Kumar, L.P.; Deepa, S.F.; Moinca, I.; Suresh, P.; Naidu, K.V. Medulloblastoma: A common pediatric tumor: Prognostic factors and predictors of outcome. Asian J. Neurosurg. 2015, 10, 50.

- Partap, S.; Curran, E.K.; Propp, J.M.; Le, G.M.; Sainani, K.L.; Fisher, P.G. Medulloblastoma Incidence has not Changed Over Time: A CBTRUS Study. J. Pediatric Hematol. Oncol. 2009, 31, 970–971.

- Rutkowski, S.; von Hoff, K.; Emser, A.; Zwiener, I.; Pietsch, T.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Giangaspero, F.; Ellison, D.W.; Garre, M.L.; Biassoni, V.; et al. Survival and prognostic factors of early childhood medulloblastoma: An international meta-analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 4961–4968.

- Medulloblastoma—Childhood: Statistics. Available online: https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/medulloblastoma-childhood/statistics (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- American Brain Tumor Association. Medullloblastoma. Available online: https://www.abta.org/tumor_types/medulloblastoma/ (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Skowron, P.; Farooq, H.; Cavalli, F.M.G.; Morrissy, A.S.; Ly, M.; Hendrikse, L.D.; Wang, E.Y.; Djambazian, H.; Zhu, H.; Mungall, K.L.; et al. The transcriptional landscape of Shh medulloblastoma. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1749.

- Taylor, M.D.; Northcott, P.A.; Korshunov, A.; Remke, M.; Cho, Y.J.; Clifford, S.C.; Eberh\art, C.G.; Parsons, D.W.; Rutkowski, S.; Gajjar, A.; et al. Molecular subgroups of medulloblastoma: The current consensus. Acta Neuropathol. 2012, 123, 465–472.

- Juraschka, K.; Taylor, M.D. Medulloblastoma in the age of molecular subgroups: A review: JNSPG 75th Anniversary Invited Review Article. J. Neurosurg. Pediatrics PED 2019, 24, 353–363.

- McNeil, D.E.; Coté, T.R.; Clegg, L.; Rorke, L.B. Incidence and trends in pediatric malignancies medulloblastoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor: A SEER update. Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results. Med. Pediatr. Oncol. 2002, 39, 190–194.

- Rochkind, S.; Blatt, I.; Sadeh, M.; Goldhammer, Y. Extracranial metastases of medulloblastoma in adults: Literature review. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1991, 54, 80–86.

- Garzia, L.; Kijima, N.; Morrissy, A.S.; De Antonellis, P.; Guerreiro-Stucklin, A.; Holgado, B.L.; Wu, X.; Wang, X.; Parsons, M.; Zayne, K.; et al. A Hematogenous Route for Medulloblastoma Leptomeningeal Metastases. Cell 2018, 172, 1050–1062.e1014.

- Bourgouin, P.M.; Tampieri, D.; Grahovac, S.Z.; Léger, C.; Del Carpio, R.; Melançon, D. CT and MR imaging findings in adults with cerebellar medulloblastoma: Comparison with findings in children. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1992, 159, 609–612.

- Colafati, G.S.; Voicu, I.P.; Carducci, C.; Miele, E.; Carai, A.; Di Loreto, S.; Marrazzo, A.; Cacchione, A.; Cecinati, V.; Tornesello, A.; et al. MRI features as a helpful tool to predict the molecular subgroups of medulloblastoma: State of the art. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 2018, 11, 1756286418775375.

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, C.H.; Kim, O.L.; Chang, C.H.; Kim, S.W.; Choi, B.Y.; Cho, S.H.; Hah, J.O. Atypical Cerebellar Medulloblastoma Originating from Tentorium: Case Report. Yeungnam. Univ. J. Med. 2007, 24, 311–314.

- Al-Sharydah, A.M.; Al-Abdulwahhab, A.H.; Al-Suhibani, S.S.; Al-Issawi, W.M.; Al-Zahrani, F.; Katbi, F.A.; Al-Thuneyyan, M.A.; Jallul, T.; Mishaal Alabbas, F. Posterior fossa extra-axial variations of medulloblastoma: A pictorial review as a primer for radiologists. Insights Imaging 2021, 12, 43.

- Kumar, R.; Achari, G.; Banerjee, D.; Chhabra, D. Uncommon presentation of medulloblastoma. Child’s Nerv. Syst. 2001, 17, 538–542.

- Chung, E.J.; Jeun, S.S. Extra-axial medulloblastoma in the cerebellar hemisphere. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2014, 55, 362–364.

- Pant, I.; Chaturvedi, S.; Gautam, V.K.; Pandey, P.; Kumari, R. Extra-axial medulloblastoma in the cerebellopontine angle: Report of a rare entity with review of literature. J. Pediatr. Neurosci. 2016, 11, 331–334.

- Perreault, S.; Ramaswamy, V.; Achrol, A.S.; Chao, K.; Liu, T.T.; Shih, D.; Remke, M.; Schubert, S.; Bouffet, E.; Fisher, P.G.; et al. MRI Surrogates for Molecular Subgroups of Medulloblastoma. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2014, 35, 1263–1269.

- Pierce, T.T.; Provenzale, J.M. Evaluation of apparent diffusion coefficient thresholds for diagnosis of medulloblastoma using diffusion-weighted imaging. Neuroradiol. J. 2014, 27, 63–74.

- Duc, N.M. The impact of magnetic resonance imaging spectroscopy parameters on differentiating between paediatric medulloblastoma and ependymoma. Contemp. Oncol. 2021, 25, 95–99.

- Schwalbe, E.C.; Lindsey, J.C.; Nakjang, S.; Crosier, S.; Smith, A.J.; Hicks, D.; Rafiee, G.; Hill, R.M.; Iliasova, A.; Stone, T.; et al. Novel molecular subgroups for clinical classification and outcome prediction in childhood medulloblastoma: A cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 958–971.

- Thompson, E.M.; Hielscher, T.; Bouffet, E.; Remke, M.; Luu, B.; Gururangan, S.; McLendon, R.E.; Bigner, D.D.; Lipp, E.S.; Perreault, S.; et al. Prognostic value of medulloblastoma extent of resection after accounting for molecular subgroup: A retrospective integrated clinical and molecular analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 484–495.

- Kumar, R.; Liu, A.P.Y.; Northcott, P.A. Medulloblastoma genomics in the modern molecular era. Brain Pathol 2020, 30, 679–690.

- Ellison, D.W.; Dalton, J.; Kocak, M.; Nicholson, S.L.; Fraga, C.; Neale, G.; Kenney, A.M.; Brat, D.J.; Perry, A.; Yong, W.H.; et al. Medulloblastoma: Clinicopathological correlates of SHH, WNT, and non-SHH/WNT molecular subgroups. Acta Neuropathol. 2011, 121, 381–396.

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Wesseling, P.; Brat, D.J.; Cree, I.A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Hawkins, C.; Ng, H.K.; Pfister, S.M.; Reifenberger, G.; et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A summary. Neuro. Oncol. 2021, 23, 1231–1251.

- Phoenix, T.N.; Patmore, D.M.; Boop, S.; Boulos, N.; Jacus, M.O.; Patel, Y.T.; Roussel, M.F.; Finkelstein, D.; Goumnerova, L.; Perreault, S.; et al. Medulloblastoma Genotype Dictates Blood Brain Barrier Phenotype. Cancer Cell 2016, 29, 508–522.

- Valcourt, D.M.; Dang, M.N.; Wang, J.; Day, E.S. Nanoparticles for Manipulation of the Developmental Wnt, Hedgehog, and Notch Signaling Pathways in Cancer. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 48, 1864–1884.

- Caimano, M.; Lospinoso Severini, L.; Loricchio, E.; Infante, P.; Di Marcotullio, L. Drug Delivery Systems for Hedgehog Inhibitors in the Treatment of SHH-Medulloblastoma. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 9.

- Huq, S.; Kannapadi, N.V.; Casaos, J.; Lott, T.; Felder, R.; Serra, R.; Gorelick, N.L.; Ruiz-Cardozo, M.A.; Ding, A.S.; Cecia, A.; et al. Preclinical efficacy of ribavirin in SHH and group 3 medulloblastoma. J. Neurosurg. Pediatrics 2021, 27, 482–488.

- Thompson, E.M.; Keir, S.T.; Venkatraman, T.; Lascola, C.; Yeom, K.W.; Nixon, A.B.; Liu, Y.; Picard, D.; Remke, M.; Bigner, D.D.; et al. The role of angiogenesis in Group 3 medulloblastoma pathogenesis and survival. Neuro Oncol. 2017, 19, 1217–1227.

- Forget, A.; Martignetti, L.; Puget, S.; Calzone, L.; Brabetz, S.; Picard, D.; Montagud, A.; Liva, S.; Sta, A.; Dingli, F.; et al. Aberrant ERBB4-SRC Signaling as a Hallmark of Group 4 Medulloblastoma Revealed by Integrative Phosphoproteomic Profiling. Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 379–395.e377.

- Gibson, P.; Tong, Y.; Robinson, G.; Thompson, M.C.; Currle, D.S.; Eden, C.; Kranenburg, T.A.; Hogg, T.; Poppleton, H.; Martin, J.; et al. Subtypes of medulloblastoma have distinct developmental origins. Nature 2010, 468, 1095–1099.

- Kool, M.; Koster, J.; Bunt, J.; Hasselt, N.E.; Lakeman, A.; van Sluis, P.; Troost, D.; Meeteren, N.S.; Caron, H.N.; Cloos, J.; et al. Integrated genomics identifies five medulloblastoma subtypes with distinct genetic profiles, pathway signatures and clinicopathological features. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3088.

- Northcott, P.A.; Korshunov, A.; Witt, H.; Hielscher, T.; Eberhart, C.G.; Mack, S.; Bouffet, E.; Clifford, S.C.; Hawkins, C.E.; French, P.; et al. Medulloblastoma comprises four distinct molecular variants. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 1408–1414.

- Rogers, H.A.; Miller, S.; Lowe, J.; Brundler, M.A.; Coyle, B.; Grundy, R.G. An investigation of WNT pathway activation and association with survival in central nervous system primitive neuroectodermal tumours (CNS PNET). Br. J. Cancer 2009, 100, 1292–1302.

- Manoranjan, B.; Venugopal, C.; Bakhshinyan, D.; Adile, A.A.; Richards, L.; Kameda-Smith, M.M.; Whitley, O.; Dvorkin-Gheva, A.; Subapanditha, M.; Savage, N.; et al. Wnt activation as a therapeutic strategy in medulloblastoma. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4323.

- Northcott, P.A.; Buchhalter, I.; Morrissy, A.S.; Hovestadt, V.; Weischenfeldt, J.; Ehrenberger, T.; Gröbner, S.; Segura-Wang, M.; Zichner, T.; Rudneva, V.A.; et al. The whole-genome landscape of medulloblastoma subtypes. Nature 2017, 547, 311–317.

- Ellison, D.W.; Kocak, M.; Dalton, J.; Megahed, H.; Lusher, M.E.; Ryan, S.L.; Zhao, W.; Nicholson, S.L.; Taylor, R.E.; Bailey, S.; et al. Definition of disease-risk stratification groups in childhood medulloblastoma using combined clinical, pathologic, and molecular variables. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 1400–1407.

- Korshunov, A.; Sahm, F.; Zheludkova, O.; Golanov, A.; Stichel, D.; Schrimpf, D.; Ryzhova, M.; Potapov, A.; Habel, A.; Meyer, J.; et al. DNA methylation profiling is a method of choice for molecular verification of pediatric WNT-activated medulloblastomas. Neuro-Oncol. 2018, 21, 214–221.

- Nobre, L.; Zapotocky, M.; Khan, S.; Fukuoka, K.; Fonseca, A.; McKeown, T.; Sumerauer, D.; Vicha, A.; Grajkowska, W.A.; Trubicka, J.; et al. Pattern of Relapse and Treatment Response in WNT-Activated Medulloblastoma. Cell Rep. Med. 2020, 1, 100038.

- Ahmad, N.; Eltawel, M.; Kashgari, A.; Alassiri, A.H. WNT-activated Pediatric Medulloblastoma Associated With Metastasis to the Suprasellar Region and Hypopituitarism. J. Pediatric Hematol./Oncol. 2021, 43, e512–e516.

- AbdelBaki, M.S.; Boué, D.R.; Finlay, J.L.; Kieran, M.W. Desmoplastic nodular medulloblastoma in young children: A management dilemma. Neuro-Oncol. 2017, 20, 1026–1033.

- Remke, M.; Hielscher, T.; Northcott, P.A.; Witt, H.; Ryzhova, M.; Wittmann, A.; Benner, A.; Deimling, A.v.; Scheurlen, W.; Perry, A.; et al. Adult Medulloblastoma Comprises Three Major Molecular Variants. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 2717–2723.

- Robinson, G.W.; Rudneva, V.A.; Buchhalter, I.; Billups, C.A.; Waszak, S.M.; Smith, K.S.; Bowers, D.C.; Bendel, A.; Fisher, P.G.; Partap, S.; et al. Risk-adapted therapy for young children with medulloblastoma (SJYC07): Therapeutic and molecular outcomes from a multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 768–784.

- Zhukova, N.; Ramaswamy, V.; Remke, M.; Pfaff, E.; Shih, D.J.H.; Martin, D.C.; Castelo-Branco, P.; Baskin, B.; Ray, P.N.; Bouffet, E.; et al. Subgroup-Specific Prognostic Implications of TP53 Mutation in Medulloblastoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 2927–2935.

- Ramaswamy, V.; Remke, M.; Bouffet, E.; Faria, C.C.; Perreault, S.; Cho, Y.-J.; Shih, D.J.; Luu, B.; Dubuc, A.M.; Northcott, P.A.; et al. Recurrence patterns across medulloblastoma subgroups: An integrated clinical and molecular analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 1200–1207.

- Samkari, A.; White, J.; Packer, R. SHH inhibitors for the treatment of medulloblastoma. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2015, 15, 763–770.

- Khatua, S.; Song, A.; Citla Sridhar, D.; Mack, S.C. Childhood Medulloblastoma: Current Therapies, Emerging Molecular Landscape and Newer Therapeutic Insights. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 16, 1045–1058.

- Northcott, P.A.; Dubuc, A.M.; Pfister, S.; Taylor, M.D. Molecular subgroups of medulloblastoma. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2012, 12, 871–884.

- Cho, Y.J.; Tsherniak, A.; Tamayo, P.; Santagata, S.; Ligon, A.; Greulich, H.; Berhoukim, R.; Amani, V.; Goumnerova, L.; Eberhart, C.G.; et al. Integrative genomic analysis of medulloblastoma identifies a molecular subgroup that drives poor clinical outcome. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 1424–1430.

- Menyhárt, O.; Giangaspero, F.; Győrffy, B. Molecular markers and potential therapeutic targets in non-WNT/non-SHH (group 3 and group 4) medulloblastomas. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 29.

- Remke, M.; Hielscher, T.; Korshunov, A.; Northcott, P.A.; Bender, S.; Kool, M.; Westermann, F.; Benner, A.; Cin, H.; Ryzhova, M.; et al. FSTL5 Is a Marker of Poor Prognosis in Non-WNT/Non-SHH Medulloblastoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 3852–3861.

- Northcott, P.A.; Shih, D.J.H.; Remke, M.; Cho, Y.-J.; Kool, M.; Hawkins, C.; Eberhart, C.G.; Dubuc, A.; Guettouche, T.; Cardentey, Y.; et al. Rapid, reliable, and reproducible molecular sub-grouping of clinical medulloblastoma samples. Acta Neuropathol. 2012, 123, 615–626.

- Northcott, P.A.; Lee, C.; Zichner, T.; Stütz, A.M.; Erkek, S.; Kawauchi, D.; Shih, D.J.; Hovestadt, V.; Zapatka, M.; Sturm, D.; et al. Enhancer hijacking activates GFI1 family oncogenes in medulloblastoma. Nature 2014, 511, 428–434.

- Morfouace, M.; Cheepala, S.; Jackson, S.; Fukuda, Y.; Patel, Y.T.; Fatima, S.; Kawauchi, D.; Shelat, A.A.; Stewart, C.F.; Sorrentino, B.P.; et al. ABCG2 Transporter Expression Impacts Group 3 Medulloblastoma Response to Chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 3879–3889.

- Ingram, W.J.; Crowther, L.M.; Little, E.B.; Freeman, R.; Harliwong, I.; Veleva, D.; Hassall, T.E.; Remke, M.; Taylor, M.D.; Hallahan, A.R. ABC transporter activity linked to radiation resistance and molecular subtype in pediatric medulloblastoma. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2013, 2, 26.

- Ramaswamy, V.; Remke, M.; Bouffet, E.; Bailey, S.; Clifford, S.C.; Doz, F.; Kool, M.; Dufour, C.; Vassal, G.; Milde, T.; et al. Risk stratification of childhood medulloblastoma in the molecular era: The current consensus. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131, 821–831.

- Łastowska, M.; Trubicka, J.; Niemira, M.; Paczkowska-Abdulsalam, M.; Karkucińska-Więckowska, A.; Kaleta, M.; Drogosiewicz, M.; Perek-Polnik, M.; Krętowski, A.; Cukrowska, B.; et al. Medulloblastoma with transitional features between Group 3 and Group 4 is associated with good prognosis. J. Neurooncol. 2018, 138, 231–240.

More