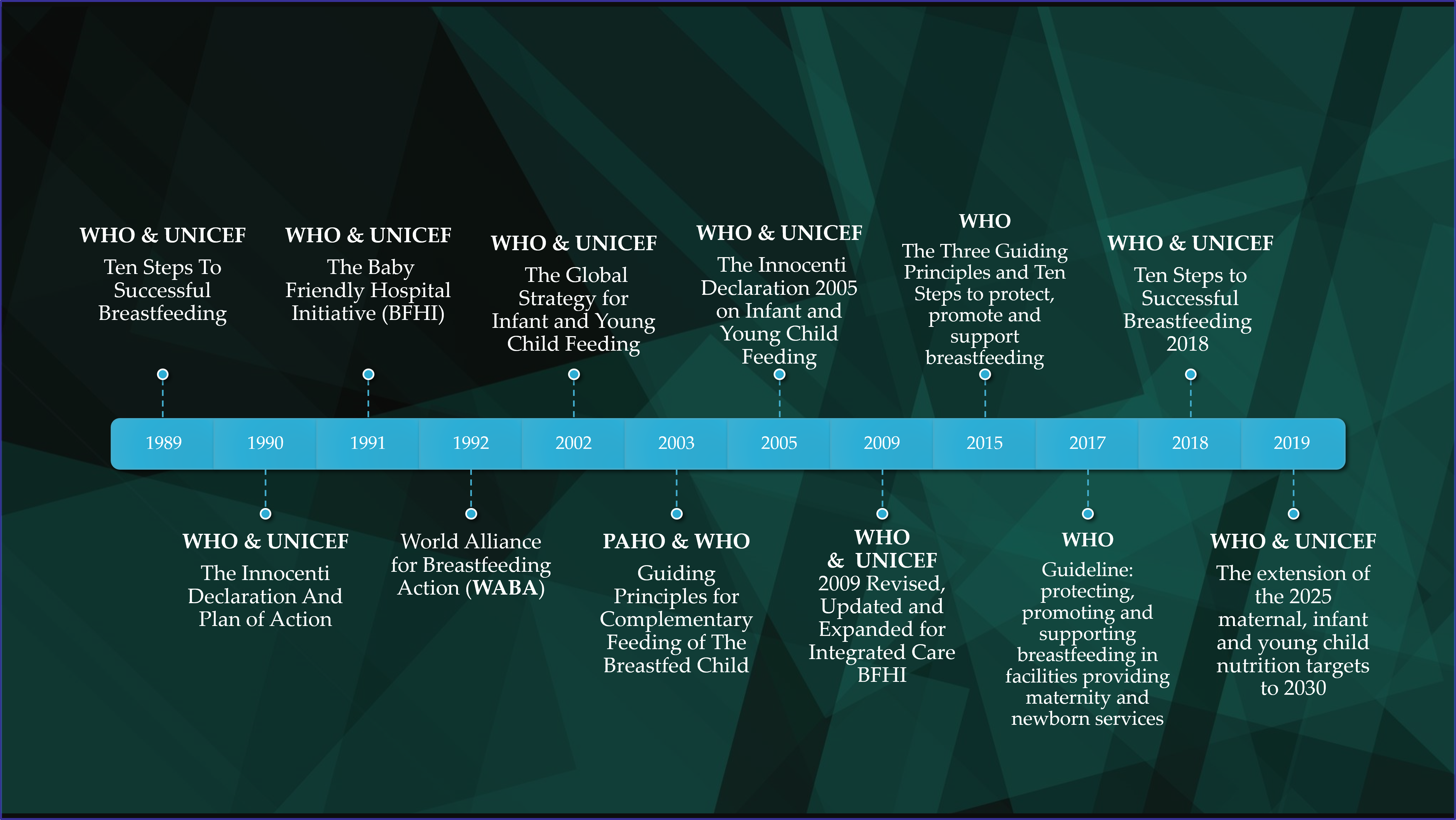

Childhood malnutrition is a global epidemic with significant public health ramifications. The alarming increase in childhood obesity rates, in conjunction with the COVID-19 pandemic, pose major challenges. Since the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1989 and the joint consortium held by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) that led to the “Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding”, several policymakers and scientific societies have produced relevant reports. Today, the WHO and UNICEF remain the key players on the field, elaborating the guidelines shaped by international expert teams over time, but there is still a long way to go before assuring the health of our children.

- nutrition policies

- breastfeeding policies

- childhood malnutrition

- infants

- young children

1. Introduction

2. A Roadmap of Global and European Policies Promoting Healthy Nutrition for Infants andYoung Children.

2.1. Breastfeeding, Complementary Feeding and Young Child Feeding Promotion

2.2. Severe Malnutrition Prevention and Management

Severe malnutrition and deprivation have also been fields of intensive research. Chronic and acute malnutrition are the clinical manifestations of the disease. Stunting signs for chronic malnutrition are often present in children with acute malnutrition. In 2009, through a joint statement, WHO and UNICEF published directions on the evaluation and assessment of the disease [52]. Several action plans have addressed the nutritional needs of children in low-and middle-income countries. Two guiding reports were issued by WHO in 1999 and 2000 respectively, in the context of severe, acute malnutrition management by physicians [53][54]. The Guideline: Updates on the management of severe acute malnutrition in infants and children presented the updated evidence regarding the recommendations for the treatment of severe acute malnutrition [55]. A joint statement by WHO, UNICEF, World Food Programme (WFP) and United Nations Standing Committee on Nutrition (UNSCN) in 2007 reflected the significance of coordinated efforts with community support towards the prevention of acute malnutrition [56]. In 2003, WHO recommended specific steps to increase breastfeeding rates in the developing WHO regions, considering the definite proof of its beneficial impact on childhood mortality [57].2.3. Prevention of Childhood Overweight and Obesity

Childhood obesity is a common major public health problem in both developed and developing countries [1]. Various policies address the topic in the context of broader plans that either refer to early childhood healthy nutrition promotion or, generally, deal with the burden of NCDs. Aiming to provide a comprehensive framework for action, WHO established the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity in 2014. Two years later, in 2016, the contextual report of it, by WHO, presented the six focus areas of specific recommendations on tackling the burden of obesity [58]. The restriction in the use of unhealthy foods and sugar-sweetened beverages by children and the promotion of healthy nutrition behaviors were highlighted by the experts in the first focus area and were further analyzed into detailed guidelines. The promotion of physical activity was the main approach of the second area, declaring the necessity of reducing sedentary behaviors in children and adolescents, which are associated with obesity and other metabolic disorders. The third area focused on the importance of comprehensive counselling in the preconception and antenatal period, aiming to the long-term benefits in children’s optimal weight and good health. A detailed matrix of steps regarding the guidance on healthy diet, sleep and physical activity for infants’ and toddlers’ caregivers was presented in the fourth area, whereas the fifth one focused on contextual programs in school environments. In the last area, a holistic approach was discussed, in respect to the management of obese children and young people through family-based, multicomponent and updated services. In 2017 WHO published a comprehensive guidance for primary health care facilities which incorporated the established recommendations and introduced new ones, regarding the prevention of childhood overweight and obesity [59]. Detailed directions were given, regarding the anthropometric and nutritional assessment of infants and children and the management of primary health care pediatric patients with acute and chronic malnutrition, overweight and obesity.2.4. Children’s Healthy Nutrition as a Goal in Broader Plans

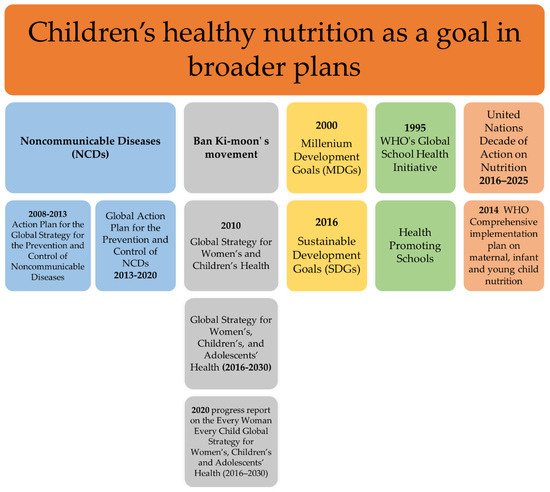

At the dawn of the new millennium, a concerted action motivated by the extreme poverty rates [60] and the aggravating global climate situation [61] resulted in the composition of an inspired contract; the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Children’s nutrition and optimal feeding in order to grow into their full potential was the main pillar of the 1st goal “Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger” [62]. An influential movement was initiated in 2010 by Ban Ki-moon, under the name of “Every Woman Every Child”, as a part of the “Global Strategy for Women’s and Children’s Health”. The strategy aimed to speed up the implementation of MDGs [63]. In 2015, the United Nations presented the appraisal of the work on MDGs and introduced the new vision of the “2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”. The eight MDGs evolved into the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Significant goals as “Zero Hunger” and “Good Health and Well-Being” demand special efforts, providing orientation and operational targets to be achieved. Prevalence of stunting and malnutrition imply progress indicators and important questions that have to be addressed through 2030 [64]. Food insecurity, as part of the 2nd Goal, is a growing challenge for most countries; FAO introduced the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) as a tool for food insecurity assessment [65]. The “Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s, and Adolescents’ Health (2016–2030)” advanced to its new mission to incorporate the SDGs into Ban Ki-moon’s initial ambition. Three major perspectives were performed, Survive-Thrive-Transform, and Thrive was the objective that includes the actions against malnutrition, as far as mothers, infants and young children are concerned [66]. With the prospect of sustainability and equity in health services, the Strategy broadened the policies into adolescents’ care and, in celebrating the 10th anniversary since 2010, the 2020 progress report on the” Every Woman Every Child Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health” (2016–2030) redefined the movement in terms of the COVID-19 pandemic. Rise, refocus and recover was the new motto, with special attention to the first of six focus areas, namely the early childhood development, that underlined the key-role of optimal feeding [67]. At the same time, a policy framework of great value was introduced in the 65th WHA in 2012, in the context of the United Nations Decade of Action on Nutrition 2016–2025 [68], proposing specific targets for implementing universally the infant and young child nutrition guidelines through 2025 [69]. Experts suggested a six-target plan with five actions aiming to achieve adherence to the framework. The 1st target directed towards the reduction of stunted children under 5 by 40%, whereas the 4th stated that the increase in the number of overweight children should come to an end, being the first statement to indicate the so-called double burden of undernutrition and overweight. WHO’s Global School Health Initiative originated as the first global effort to establish optimal school conditions in 1995 [70]. The vision was to embrace needs of all children with future perspective of health and well-being. The so-called “Health Promoting Schools” have been still working on forming their environment to control the determinants of health. The sector of nutrition remained a focus target. Another attempt to promote healthy nutrition practices was made through creating intervention plans to reduce modifiable risk factors for NCDs. The term refers to cancers, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and chronic lung illnesses. Common risk factors include tobacco use, harmful alcohol intake, physical inactivity and the adoption of unhealthy dietary patterns. In the year 2000, stakeholders welcomed the first WHO resolution for the prevention and control of NCDs, providing general guidance on the topic, without however, mentioning the needs of children [71]. The 2008–2013 Action Plan for the Global Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases, published by WHO, provided recommendations for exclusive breastfeeding during the first six months of life and stated for healthier composition of foods, concerning children [72]. The suggested goals were reaffirmed by the updated Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs 2013–2020 and current actions have been developed in the context of the “2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” [64][73]. Figure 2 summarizes the aforementioned broader plans.

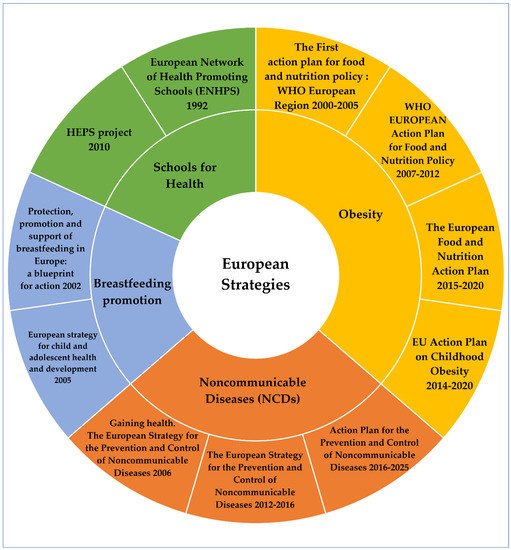

2.5. Strategies and Action Plans in the European Region

International nutrition policies tried to highlight the significance of an integrated approach in the promotion of children’s healthy nutrition; similar actions and policy frameworks have appeared over time in the European region as well. David Byrne, the European Commissioner for Health and Consumer Protection, at the EU Conference on Promotion of Breastfeeding in Europe on the 18th of June 2004, presented the Protection, promotion and support of breastfeeding in Europe: a blueprint for action. That was the first European action plan in the field of breastfeeding promotion and support, which had been developed two years earlier [74]. In accordance with the MDGs, the WHO regional office for Europe in 2005, developed the European strategy for child and adolescent health and development, stating the importance of the early years of life in establishing optimal nutrition practices [75]. The rising rates of childhood obesity in the following years led to the launch of the EU Action Plan on Childhood Obesity 2014–2020 in 2014, which aimed to suspend the accelerating increase of the problem among children and young people aged 0–18 years [76]. A parallel strategy was developed one year later by WHO, the European Food and Nutrition Action Plan 2015–2020, aiming to combat the preventable diet-related NCDs, obesity, and all other forms of malnutrition [77]. There had been two previous similar documents, The First action plan for food and nutrition policy: WHO European Region 2000–2005 and the WHO EUROPEAN Action Plan for Food and Nutrition Policy 2007–2012 that had tried to provide an initial framework for children’s nutrition [78][79]. An inspired program was the Schools for Health in Europe (SHE) Network Foundation, formerly named European Network of Health Promoting Schools (ENHPS), in 1992 [80]. One of the specified target points was healthy nutrition promotion and practices through schools. The SHE has continued working on advancing the educational role of schools into a holistic approach to students’ needs and for this purpose has provided support and useful material for national implementation [81]. The Healthy Eating and Physical activity in Schools (HEPS) project is a European project linked with the SHE network, aiming to offer guidance for school policy development on healthy eating and physical activity in the European region. The HEPS toolkit consists of six documents that direct to help EU member states develop their own policies [82]. Furthermore, the vision of the Best-ReMaP project 2020–2023, entitled “Healthy food for a Healthy Future” is a European joint action aiming to exchange nutrition policies and control the marketing of food and beverages to children [83]. The fight against NCDs entered the European Agenda in 2006, in compliance with the corresponding international action plans. A report entitled Gaining health. The European Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases and the following resolution of the Regional Committee was the first step, with special mention to reducing levels of added salt, fat and sugars in children’s nutrition [84][85]. The European Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2012–2016 and the following action plan for its implementation focused again on the necessity to control the marketing of processed food aimed at children [86]. The current Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases in the WHO European Region 2016–2025 set as a priority area the food product reformulation and improvement, among others, but the initiators called for caution about the adequate iodine intake by children [87]. Figure 3 details the European nutrition strategies for healthy children without any malnutrition form, in a graphical manner.

3. Discussion

The concept of establishing the principles of healthy nutrition on pediatrics arose in late 80’s. It is only then, that the international stakeholders decided to endorse a policy, calling for action in the field of newborns’ feeding, inspired by the pronouncement about the infants’ rights to adequate nutritious foods signified in 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child [91]. Henceforth, the aforementioned policies have been widely accepted and several national strategies and action plans have been developed, incorporating childhood nutritional guidelines, and introducing new perspectives. However, the need for further implementation, evaluation and critical appraisal of the existing policies should be acknowledged. Aiming to elucidate the factors leading to childhood malnutrition, WHO members periodically assemble over time, issuing reports and statements which subsequently are adopted by the WHO Regional Office for Europe. According to the WHA 62.14 document, inequities in children’s health demand actions on the social determinants of health [92]. Extreme poverty, economic instability and urbanization modify health outcomes and hamper children’s way to flourish [93]. The heads of the WHO Regional office for Europe declared that “children’s obesity is the clearest demonstration of the strength of environmental influences and the failure of the traditional prevention strategies based only on health promotion” [94]. The main documents with reference to childhood overweight and obesity [58][59][67][69][70][72][73][76][77][81][85][86][87][90], published by international and European organizations, are shown in Table 1.| Policies | Publication Year | Organization | Target Population |

| Health Promoting Schools | NA | WHO | International |

| Extended International (IOTF) Body Mass Index Cut-Offs for Thinness, Overweight and Obesity in Children | NA | IOTF | International |

| Gaining health. The European Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases | 2006 | WHO Europe | Europe |

| 2008–2013 Action Plan for the Global Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases | 2009 | WHO | International |

| Healthy Eating and Physical activity in Schools (HEPS) project | 2010 | The Schools for Health in Europe network (SHE) | Europe |

| Action plan for implementation of the European Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2012−2016 | 2012 | WHO Europe | Europe |

| Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs 2013–2020 | 2013 | WHO | International |

| WHO Comprehensive implementation plan on maternal, infant and young child nutrition | 2014 | WHO | International |

| EU Action Plan on Childhood Obesity 2014–2020 | 2014 | European Commission | Europe |

| European Food and Nutrition Action Plan 2015–2020 | 2015 | WHO Europe | Europe |

| Report of the commission on ending childhood obesity | 2016 | WHO | International |

| Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases in the WHO European Region 2016–2025 | 2016 | WHO Europe | Europe |

| Guideline: assessing and managing children at primary health-care facilities to prevent overweight and obesity in the context of the double burden of malnutrition | 2017 | WHO | International |

| Protect the progress: rise, refocus and recover | 2020 | WHO & UNICEF | International |

4. Conclusions

Since 2003, when the executive heads of WHO and UNICEF announced that “There can be no delay in applying the accumulated knowledge and experience to help make our world a truly fit environment where all children can thrive and achieve their full potential”, remarkable efforts have been made to address the problem of childhood malnutrition. Current health estimates, however, show significant delays on the progress. The children of the world hope for food security and equity in resources, indicating that considerable steps are pending.

References

- Vassilakou, T. Childhood Malnutrition: Time for Action. Children 2021, 8, 103.

- World Health Organization. Malnutrition. Available online: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Popkin, B.M.; Corvalan, C.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M. Dynamics of the double burden of malnutrition and the changing nutrition reality. Lancet 2020, 395, 65–74.

- Biesalski, H.K.; O’Mealy, P. Hidden Hunger, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013.

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Hunger and Food Insecurity. Available online: https://www.fao.org/hunger/en/ (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Economic Research Service; U.S. Department of Agriculture. Definitions of Food Security. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/definitions-of-food-security/ (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Food and Agriculture Organization. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World: Safeguarding against Economic Slowdowns and Downturns; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2019.

- Food Security Information Network. Global Report on Food Crises; World Food Programme: Rome, Italy, 2019.

- World Health Organization. Levels and Trends in Child Malnutrition: UNICEF/WHO/The World Bank Group Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates: Key Findings of the 2020 Edition; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Cheryl, D.; Fryar, M.S.P.H.; Margaret, D.; Carroll, M.S.P.H.; Afful, J. Prevalence of Overweight, Obesity, and Severe Obesity among Children and Adolescents Aged 2–19 Years: United States, 1963–1965 through 2017–2018; NCHS Health E-Stats: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020.

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe. WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (COSI). Report on the Fourth Round of Data Collection 2015–2017; World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021.

- Stavridou, A.; Kapsali, E.; Panagouli, E.; Thirios, A.; Polychronis, K.; Bacopoulou, F.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Tsolia, M.; Sergentanis, T.N.; Tsitsika, A. Obesity in Children and Adolescents during COVID-19 Pandemic. Children 2021, 8, 135.

- Lange, S.J.; Kompaniyets, L.; Freedman, D.S.; Kraus, E.M.; Porter, R. Longitudinal trends in body mass index before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among persons aged 2–19 years—United States, 2018–2020. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 1278.

- International Food Policy Research Institute. 2014 Global Hunger Index: The Challenge of Hidden Hunger; Welthungerhilfe, International Food Policy Research Institute: Bonn, Germany; Washington, DC, USA; Concern Worldwide: Dublin, Ireland, 2014.

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Nieman, P.; Leblanc, C.M. Psychosocial aspects of child and adolescent obesity. Paediatr. Child Health 2012, 17, 205–208.

- Sahoo, K.; Sahoo, B.; Choudhury, A.K.; Sofi, N.Y.; Kumar, R.; Bhadoria, A.S. Childhood obesity: Causes and consequences. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 2015, 4, 187–192.

- Lifshitz, F. Obesity in children. J. Clin. Res. Pediatric Endocrinol. 2008, 1, 53–60.

- Marshall, N.E.; Abrams, B.; Barbour, L.A.; Catalano, P.; Christian, P.; Friedman, J.E.; Hay, W.W., Jr.; Hernandez, T.L.; Krebs, N.F.; Oken, E.; et al. The importance of nutrition in pregnancy and lactation: Lifelong consequences. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226, 607–632.

- Moore, B.F.; Harrall, K.K.; Sauder, K.A.; Glueck, D.H.; Dabelea, D. Neonatal Adiposity and Childhood Obesity. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20200737.

- Walters, E.; Edwards, R.G. Further thoughts regarding evidence offered in support of the ‘Barker hypothesis’. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2004, 9, 129–131.

- Barker, D.J.; Eriksson, J.G.; Forsen, T.; Osmond, C. Fetal origins of adult disease: Strength of effects and biological basis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2002, 31, 1235–1239.

- Li, R.; Ware, J.; Chen, A.; Nelson, J.M.; Kmet, J.M.; Parks, S.E.; Morrow, A.L.; Chen, J.; Perrine, C.G. Breastfeeding and Post-perinatal Infant Deaths in the United States, A National Prospective Cohort Analysis. Lancet Reg. Health-Am. 2022, 5, 100094.

- Victora, C.G.; Bahl, R.; Barros, A.J.; Franca, G.V.; Horton, S.; Krasevec, J.; Murch, S.; Sankar, M.J.; Walker, N.; Rollins, N.C. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet 2016, 387, 475–490.

- World Health Organization. Breastfeeding. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/breastfeeding#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Protecting, Promoting and Supporting Breast-Feeding: The Special Role of Maternity Services; 9241561300; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1989.

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). On the Protection, Promotion, and Support of Breastfeeding. Breastfeeding in the 1990s: Global Initiative; Spedale degli Innocenti: Florence, Italy, 1990.

- UNICEF. World Declaration on the Survival, Protection and Development of Children and Plan of Action for Implementing the World Declaration on the Survival, Protection and Development of Children; United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund: New York, NY, USA, 1990.

- World Health Organization. Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative. Available online: https://apps.who.int/nutrition/topics/bfhi/en/index.html (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action. World Breastfeeding Week (WBW). Available online: https://waba.org.my/wbw/ (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- World Health Organization. The optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. In Report of an Expert Consultation; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001.

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding; 9241562218; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

- Pan American Health Organization; WHO. Guiding Principles for Complementary Feeding of the Breastfed Child; Division of Health Promotion and Protection/Food and Nutrition Program: Washington, DC, USA, 2003.

- UNICEF. 1990–2005 Celebrating the Innocenti Declaration on the Protection, Promotion and Support of Breastfeeding; UNICEF: Florence, Italy, 2005.

- UNICEF. Innocenti Declaration on Infant and Young Child Feeding; UNICEF: Florence, Italy, 2005.

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative, revised, updated and expanded for integrated care, Section 2. Strengthening and sustaining the baby-friendly hospital initiative: A course for de-cision-makers; Section 3. In Breastfeeding Promotion and Support in a Baby-Friendly Hospital: A 20-Hour Course for Maternity Staff; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- Nyqvist, K.H.; Maastrup, R.; Hansen, M.; Haggkvist, A.; Hannula, L.; Ezeonodo, A.; Kylberg, E.; Haiek, L. Neo-BFHI: The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative for Neonatal Wards; Nordic and Quebec Working Group: Quebec, QC, Canada, 2015.

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Protecting, Promoting and Supporting Breastfeeding in Facilities Providing Maternity and Newborn Services; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Protecting, Promoting and Supporting Breastfeeding in Facilities Providing Maternity and Newborn Services: Implementing the Revised Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative 2018; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The Extension of the 2025 Maternal, Infant and Young Child Nutrition Targets to 2030; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF): New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- World Health Organization. Indicators for Assessing Breast-Feeding Practices: Report of an Informal Meeting; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1991.

- World Health Organization. Indicators for Assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Indicators for Assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices: Definitions and Measurement Methods; 9240018387; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland; United Nations Children’s Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2021.

- World Health Organization. Breastfeeding Counselling: A training Course; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1993.

- World Health Organization. Infant and Young Child Feeding Counselling: An Integrated Course; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Postnatal Care of the Mother and Newborn; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- World Health Organization. Early Essential Newborn Care: Clinical Practice Pocket Guide; WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific: Manila, Philippines, 2014.

- World Health Organization. Infant and Young Child Feeding: Model Chapter for Textbooks for Medical Students and Allied Health Professionals; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- World Health Organization. Essential Newborn Care Course; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- World Health Organization. International Code of Marketing of Breast-Milk Substitutes; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1981.

- World Health Organization. Country Implementation of the International Code of Marketing of Breast-Milk Substitutes: Status Report 2011; 9241505982; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). WHO Child Growth Standards and the Identification of Severe Acute Malnutrition in Infants and Children; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- World Health Organization. Management of Severe Malnutrition: A Manual for Physicians and Other Senior Health Workers; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999.

- World Health Organization. Management of the Child with a Serious Infection or Severe Malnutrition: Guidelines for Care at the First-Referral Level in Developing Countries; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000.

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Updates on the Management of Severe ACUTE malnutrition in Infants and Children; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; pp. 6–54.

- WHO; UNICEF; WFP; UNSCN. Community-Based Management of Severe Acute Malnutrition: A Joint Statement by the World Health Organization, the World Food Programme, the United Nations System Standing Committee on Nutrition and the United Nations Children’s Fund; 9280641476; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA; WFP: Rome, Italy; UNSCN: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- World Health Organization. Community-Based Strategies for Breastfeeding Promotion and Support in Developing Countries; 9241591218; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

- World Health Organization. Report of the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Assessing and Managing Children at Primary Health-Care Facilities to Prevent Overweight and Obesity in the Context of the Double Burden of Malnutrition; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- United Nations. We Can End Poverty. Available online: https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/poverty.shtml (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- United Nations. Goal 7: Ensure Environmental Sustainability. Available online: https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/environ.shtml (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- United Nations. We Can End Poverty. Millennium Development Goals and beyond 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/ (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Ban Ki-moon, B. Global Strategy for Women’s and Children’s Health; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2010.

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2015.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.fao.org/sustainable-development-goals/goals/goal-2/en/ (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- World Health Organization. Every Woman Every Child—The Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health (2016–2030): Survive, Thrive, Transform; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Protect the Progress: Rise, Refocus and Recover: 2020 Progress Report on the “Every Woman Every Child Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health” (2016–2030); 9240011994; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- United Nations System Standing Committee on Nutrition. United Nations Decade of Action on Nutrition 2016–2025; A/RES/70/259; United Nations System Standing Committee on Nutrition: Rome, Italy, 2016.

- World Health Organization. Comprehensive Implementation Plan on Maternal, Infant and Young Child Nutrition; No. WHO/NMH/NHD/14.1; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- World Health Organization. Health Promoting Schools. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-promoting-schools#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- World Health Organization Assembly. Fifty-Third World Health Assembly, Geneva, 15–20 May 2000: Resolutions and Decisions, Annex; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000.

- World Health Organization. Action Plan for the Global Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs 2013–2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- Cattaneo, A. Protection, Promotion and Support of Breastfeeding in Europe: A Blueprint for Action; EU Project Contract N. SPC; Unit for Health Services Research and International Health: Trieste, Italy, 2004; p. 2002359.

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. European Strategy for Child and Adolescent Health and Development; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2005.

- European Commission. EU Action Plan on Childhood Obesity 2014–2020; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014.

- World Health Organization. European Food and Nutrition Action Plan 2015–2020; Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. WHO European Action Plan for Food and Nutrition Policy 2007–2012; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2008.

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. The First Action Plan for Food and Nutrition Policy: WHO European Region 2000–2005; Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2001.

- Barnekov, V.; Buijs, G.; Clift, S.; Jensen, B.; Paulus, P.; Rivett, D.; Young, I. The Health Promoting School: A Resource for Developing Indicators; International Planning Committee of the European Network of Health Promoting Schools: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2006.

- The Schools for Health in Europe Network (SHE). Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/Life-stages/child-and-adolescent-health/the-schools-for-health-in-europe-network-she (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Simovska, V.; Dadaczynski, K.; Viig, N.G.; Tjomsland, H.E.; Bowker, S.; Woynarowska, B.; de Ruiter, S.; Buijs, G. HEPS Tool for Schools: A Guide for School Policy Development on Healthy Eating and Physical Activity. HEPS: Woerden, The Netherlands, 2010.

- European Union. Healthy Food for a Healthy Future Best-ReMaP Joint Action of the European Union. Available online: https://bestremap.eu/ (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- WHO/Europe. Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases in the WHO European Region; Resolution EUR/RC56/R2; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- WHO/Europe. Gaining Health. The European Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- World Health Organization. Action Plan for Implementation of the European Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2012–2016; 9289002689; Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- World Health Organization. Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases in the WHO European Region; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016.

- Kuczmarski, R.J.; Ogden, C.L.; Guo, S.S.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M.; Flegal, K.M.; Mei, Z.; Wei, R.; Curtin, L.R.; Roche, A.F.; Johnson, C.L. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: Methods and development. Vital Health Stat. 2002, 246, 1–190.

- Gama, A.; Rosado-Marques, V.; Machado-Rodrigues, A.M.; Nogueira, H.; MourAo, I.; Padez, C. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in 3-to-10-year-old children: Assessment of different cut-off criteria WHO-IOTF. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2020, 92, e20190449.

- International Association for the Study of Obesity. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20040824052003/http://www.iotf.org/ (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- UN General Assembly. Convention on the Rights of the Child. United Nations Treaty Ser. 1989, 1577, 1–23.

- World Health Assembly. Reducing Health Inequities through Action on the Social Determinants of Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- United Nations. World Social Report 2020; Inequality in a Rapidly Changing World; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- World Health Organization Europe. The Challenge of Obesity in the WHO European Region and the Strategies for Response; World Health Organization Europe: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- World Health Organization. Sexual, Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health Policy Survey, 2018–2019: Summary Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Akseer, N.; Kandru, G.; Keats, E.C.; Bhutta, Z.A. COVID-19 pandemic and mitigation strategies: Implications for maternal and child health and nutrition. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 251–256.

- Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Cunningham, K.; Moran, V.H. COVID-19 and maternal and child food and nutrition insecurity: A complex syndemic. Matern. Amp Child Nutr. 2020, 16, e13036.

- Ntambara, J.; Chu, M. The risk to child nutrition during and after COVID-19 pandemic: What to expect and how to respond. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 3530–3536.