Grain legumes are a rich source of dietary protein for millions of people globally and thus a key driver for securing global food security. Legume plant-based ‘dietary protein’ biofortification is an economic strategy for alleviating the menace of rising malnutrition-related problems and hidden hunger. Malnutrition from protein deficiency is predominant in human populations with an insufficient daily intake of animal protein/dietary protein due to economic limitations, especially in developing countries. Therefore, enhancing grain legume protein content will help eradicate protein-related malnutrition problems in low-income and underprivileged countries.

- grain legume

- protein

- biofortification

1. Introduction

2. Grain Legumes as an Important Source of Dietary Protein

Grain legumes vary in their protein content, due to fundamental limitations on the components a seed must contain to be viable. Many grains legumes have 25–40% SPC, and it may be difficult to raise that number much beyond 40%. (See Table 1).| Crop | Scientific Name | Range of Grain Seed Protein Content | References | Deficient Amino Acids | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chickpea |  |

Cicer erietinum | L. | 17–22% before dehulling | [8][9] | [14,15] | Methionine, cysteine threonine and valine [10] | Methionine, cysteine threonine and valine [16] |

| 25.3–28.9% after dehulling | ||||||||

| Lentil |  |

Lens culinaris | Medik | 20.6% and 31.4% | [11] | [17] | Methionine, cysteine [12] | Methionine, cysteine [18] |

| Lupin |  |

Lupinus albus | L. | 35–44% | [13][14] | [19,20] | Alanine, tryptophan [15] | Alanine, tryptophan [21] |

| Soybean |  |

Glycine max | (L.) Merr. | up to 40% | [16][17] | [22,23] | Methionine, cysteine, threonine and lysine [18] | Methionine, cysteine, threonine and lysine [24] |

| Common bean |  |

Phaseolous vulgaris | L. | 20–30% | [19][20] | [25,26] | Methionine, cysteine [21] | Methionine, cysteine [27] |

| Pigeonpea |  |

Cajanus cajan | (L.) Millsp | 20–22% | [22] | [28] | Methionine, cysteine, valine [23] | Methionine, cysteine, valine [29] |

| Faba bean |  |

Vicia faba | L. | 26% to 41% | [24][25] | [30,31] | Methionine | |

| Mung bean |  |

Vigna radiata | L. | 20.97–31.32% | [26] | [32] | Methionine, cysteine | |

| Cowpea |  |

Vigna unguiculata | L. Walp.) | 14.8–25% | [27][28][29] | [33,34,35] | Methionine | |

| Pea |  |

Pisum sativum | L. | 13.7 to 30.7% | [30][31][32] | [36,37,38] | Methionine, cysteine and tryptophan [33] | Methionine, cysteine and tryptophan [39] |

| [31][32][33] | [37,38,39] | |||||||

| Urd bean |  |

Vigna mungo | L. Hepper | 25–28% | [34][35] | [40,41] | Methionine, cysteine | |

| Lathyrus |  |

Lathyrus sativus | L. | 8.6–34.6% | [36] | [42] | Methionine, cysteine |

3. Harnessing Genetic Variability for Improving Seed Protein Content in Grain Legumes

Harnessing crop germplasm diversity is an economical way to improve important breeding traits, including SPC in grain legume crops [37][38][39][40][41][75,76,77,78,79]. Crop genetic resources are the key reservoir for exploring high-SPC genotypes in grain legumes. Considerable amounts of genetic variability for SPC have been captured in chickpea [40][42][43][78,80,81], such as 12.4–31.5% [44][82], 17–22% [45][83], and 14.6–23.2% [46][84]. Serrano et al. [46][84] identified several high SPC genotypes (LEGCA608, LEGCA609, LEGCA614, LEGCA619, LEGCA716) that could be used to improve chickpea SPC in elite cultivars. Cowpea is a cheap source of protein for improving human nutrition. Boukar et al. [39][77] assessed a set of 1541 cowpea lines for genetic variability in grain protein content and mineral profiles. They reported a wide range of genetic variability for SPC (17.5–32.5%), including TVu-2508 (32.2%) [39][77]. Likewise, Weng et al. [47][85] screened 173 cowpea accessions collected from various parts of the world at two locations (Fayetteville and Alma, Arkansas). They also reported a substantial amount of genetic variability for SPC (22.8–28.9%), including PI 662992 (28.9%), PI 601085 (28.5%), PI 255765 (28.4%), PI 255774 (28.4%), and PI 666253 (28.4%) [47][85], which could be used to transfer the high SPC trait into high-yielding elite cowpea varieties. Grasspea is an inherent climate-resilient grain legume with an excellent source of SPC. An evaluation of 37 grasspea genotypes identified IC127616 rich in SPC (32.2%) [48][95]. Genetic variability for SPC in lentil ranges from 20 to 30% [38][49][50][51][52][76,114,115,116,117]. Likewise, lentil crop wild relatives (CWRs) have significant genetic variability for SPC, such as L. orientalis (18.3–27.75%) and L. ervoides (18.9–32.7%) [53][96], which could be used in breeding programs to improve SPC in elite lentil cultivars. Breeding for high SPC in soybean is a primary objective in soybean breeding programs; however, progress has been limited by the negative relationship between SPC and grain yield and oil content [18][54][24,130]. For example, Bandillo et al. [55][131] and Warrington et al. [56][132] reported a highly negative correlation between the soybean SPC allele and seed oil content, reducing oil content by 1% for every 2% increase in SPC. High-protein soybean lines include Danbaegkong (48.9%) [57][133] and Kwangankong (44.7%) [58][134], and TN11-5102 selected from 5601T cultivar (421 g kg−1 protein on a dry weight basis) [59][108]. Apart from cultivated species, soybean CWRs (e.g., Glycine soja) are an important source of high-protein QTLs [60][61][62][135,136,137]. A population developed by incorporating exotic soybean germplasm exhibited significant genetic variability for SPC [63][138].4. Mendelian Inheritance of Seed Protein Content in Legumes

Perez et al. [64][147] revealed the genetic basis of high and low SPC in pea using the genetics of seed size (round vs. wrinkled). They found that round-seeded pea plants (RR/RbRb) had low SPC with low albumin content, while those with recessive alleles (rr/rbrb) had high SPC and high albumin content [64][147]. High heritability of protein content and its control by a few gene(s) is an opportunity to improve protein content in cowpea [65][92]. Moreover, diallel crosses of six populations derived from two high-protein lines and two high-yielding soybean lines revealed a significant negative correlation between protein content and yield in the high protein × high protein population but a significant positive correlation between protein content and yield in the high yielding × high yielding population [66][148]. In pigeon pea, an analysis of F1 and F2 progenies derived from crosses involving four parents revealed a minimum of 3–4 genes controlling protein content [67][149]. The scholarauthors concluded that the low protein trait is partially dominant over the high protein trait.

5. QTL Mapping for Seed Protein Content

Advances in grain legume genomics have facilitated the identification of underlying QTLs controlling SPC using biparental mapping populations in various grain legumes [68][69][70][71][72][118,119,155,156,157]. In pea, using an F2-derived Wt10245 × Wt11238 mapping population, Irzykowska and Wolko [73][159] mapped five QTLs governing SPC on LG2, LG5, and LG7, explaining 13.1–25.8% PV. Subsequently, two F5 mapping populations developed from Wt11238 × Wt3557 and Wt10245 × Wt11238 revealed a QTL for protein content on LGVb flanked by cp, gp, and te markers [68][118]. Likewise, genotyping an Orb × CDC Striker RIL mapping population with SNP markers identified two SPC QTLs on LG1b, explaining 16% PV, and two on LG4a, explaining 10.2% PV, and genotyping a Carerra × CDC Striker RIL-based mapping population identified four SPC QTLs on LG7b, explaining 13% PV, and one on LG3b [74][160]. In soybean, the SPC trait is controlled by multiple alleles and highly influenced by G × E interactions [75][150]. More than 300 QTLs contributing to SPC in soybean have been reported (http://www.soybase.org, (accessed on 10 May 2022)); [76][161] and reside across all chromosomes; however, major SPC QTLs are on chromosomes 5, 15, and 20. Diers et al. [70][155] first reported a major QTL governing high SPC on chromosome 20 in a population developed from crossing cultivated and wild soybean, which was later mapped to a 3 cM on LGI (Nichols et al., 2006) [71][156]. The location of this QTL was subsequently narrowed to 8.4 Mb [77][162], <1 MB [78][163], 77.4 kb [62][137], and even with only three candidate genes [55][131] on LG20. SSR, DArT, and DArTseq analysis of five RIL-based mapping populations for high and low SPC and one high × high SPC identified two major QTLs controlling SPC on LG15 and LG20 in soybean [79][168]. Furthermore, bulk segregation analysis of four high × low SPC mapping populations unveiled novel SPC-controlling genomic regions on LG1, 8, 9, 14, 16, 17, 19, and 20 [79][168]. An assessment of soybean RILs developed from Linhefenqingdou × Meng 8206 in six different environments identified 25 SPC QTLs explaining up to 26.2% PV [80][169]. Of the identified QTLs, qPro-7-1 was highly stable across all tested environments. Recently, Fliege et al. [62][137] cloned a major SPC governing QTL (cqSeed protein-003) and elucidated the underlying causative candidate gene Glyma.20G85100, encoding a CCT domain protein. Thus, efforts are needed to fine map or clone major QTLs controlling SPC in other grain legumes to delineate the underlying candidate gene(s) and their function for genomic-assisted breeding to improve SPC in grain legumes.6. Underpinning Genomic Region/Haplotypes Controlling High Protein Content through GWAS

Traditional biparental QTL mapping for obtaining genetic recombinants controlling complex traits such as protein content is limited due to the incorporation of only two parents in the crossing program. However, the increased capacity of next generation sequencing technology to derive single nucleotide polymorphism molecular markers in association with advanced phenotyping facilities has facilitated the development of numerous genetic recombinants and identification of the underlying plausible candidate genomic regions controlling protein content in various grain legumes using GWAS [43][81][82][83][81,174,183,186]. Jadhav et al. [43][81] performed association mapping for SPC using SSR markers on a panel of 187 chickpea genotypes (desi, kabuli, and exotic). Nine significant marker trait associations (MTAs) for SPC were uncovered on LG1, LG2, LG3, LG4, and LG5, explaining 16.85% PV. A recent GWAS using high-throughput SNP markers on 140 chickpea genotypes subjected to drought and heat stress to shed light on MTAs with various nutrients uncovered 66 (non-stress), 46 (drought stress), and 15 (heat stress) MTAs for SPC [84][199], which could be used to identify high-protein lines for improving SPC in chickpea. A GWAS relying on multilocation and multi-year phenotyping of a large set of pea germplasm representing diverse regions across the globe was undertaken to identify significant MTAs for agronomic and quality traits, including protein content [81][174]. Two significant MTAs controlling SPC were identified: Chr3LG5_138253621 and Chr3LG5_194530376. GWAS using 16,376 SNPs in 332 chickpea genotypes (desi and kabuli) delineated seven genomic loci controlling SPC and explaining 41% combined PV [85][170].7. Functional Genomics Shedding Light on Causal Candidate Gene(s) Contributing Seed Protein Content in Grain Legumes

In the last decade, unprecedented advances in RNA sequencing have expedited functional genomics research, especially transcriptome analysis for discovering trait gene(s), in various grain legumes [86][197]. Numerous studies have elucidated various SPC-contributing candidate gene(s) and their functional roles in grain legumes; notably, cDNA cloning based functional characterization of genes encoding storage proteins such as pea seed albumin (PA1, PA1b) [87][201] and conglutin family in narrow leaf lupin [88][202]. Functional characterization of genes encoding storage protein in narrow leaf lupin by sequencing cDNA clones from developing seed identified 11 new storage protein (conglutin family)-encoding genes [88][202]. Transcriptome analysis via RNA-seq shed light on 16 conglutin genes encoding storage protein in the Tanjil cultivar of narrow leaf lupin [89][203]. Conglutin gene(s) expression is similar in lupin varieties of the same species but distinct between species [89][203]. In soybean, functional genomic analysis via gene expression profiling identified 329 differentially expressed genes underlying qSPC_20–1 and qSPC_20–2 QTL regions accounting for SPC using a QTL-seq approach [86][197]. Of the nine candidate genes underlying these QTL regions, Glyma.20G088000, Glyma.20G111100, and Glyma.20 g087600 were functionally validated and identified as the most potential candidate genes controlling SPC [86][197].8. Proteomics and Metabolomics Shed Light on the Genetic Basis of High Seed Protein Content in Legumes

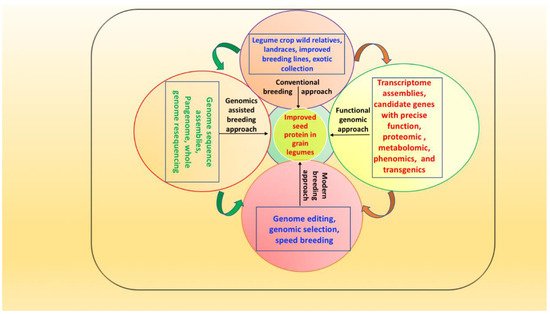

Proteomics helps peopleus understand the entire set of proteins produced at a specific time under a particular set of conditions in an organism or cell [90][204]. This approach could be used to discover novel seed storage proteins and inquire about the molecular basis of enhancing SPC in various legumes [91][205]. A novel protein known as methionine-rich protein was discovered in soybean using a two-dimensional (2D) electrophoresis technique [91][205]. Later, a 2D-PAGE proteomic tool distinguished wild soybean (G. soja) from cultivated soybean based on high storage proteins (beta-conglycinin and glycinin) detecting 44 protein spots in wild soybean and 34 protein spots in cultivated soybean; thus, this helped in identifying high-protein soybean genotypes [92][206]. Combined SDS-PAGE and MALDI-TOF MS analysis in LG00-13260, PI 427138, and BARC-6 soybean genotypes revealed enhanced accumulation of beta-conglycinin and glycinins and thus high grain protein content compared to William 82 ([93][207]. A combined SDS-PAGE and MALDI-TOF MS analysis, comparing protein content in nine soybean accessions with William 82, revealed significant protein content differences in seed 11S storage globulins [94][208]. In common bean, proteome analysis of common bean deficient in seed storage proteins (phaseolin and lectins) revealed elevated sulfur amino acid content due to increased legumin, albumin 2, and defensin [95][209]. Santos et al. [96][210] characterized the protein content of 24 chickpea genotypes using a proteomics approach to explore genetic variability in storage protein. High-performance liquid chromatography analysis indicated the presence of sufficient genetic variability for SPC, with some genotypes rich in seven amino acids. In pea, a mature seed proteome map of a diverse set of 156 proteins identified novel storage proteins for enhanced SPC [97][211]. A metabolomics study using GC-TOF/MS in contrasting seed protein soybean lines showed a high abundance of metabolites (asparagine, aspartic acid, glutamic acid, free 3-cyanoalanine) that were positively associated with SPC and negatively associated with seed oil content [98][216]. However, various sugars (sucrose, fructose, glucose, mannose) had negative associations with seed protein and oil content [98][216]. Saboori-Robat et al. [99][218] undertook metabolite profiling of common bean genotypes differing in S-methylcysteine accumulation in seeds and found that S-methylcysteine accumulates as γ-glutamyl-S-methylcysteine during seed maturation, with a low accumulation of free methylcysteine. Amino acid profiling of Valle Agricola, a nutritionally rich chickpea genotype cultivated in southern Italy, revealed that 66% of the total amino acids comprised glutamic acid, glutamine, aspartic acid, phenyl alanine, asparagine, lysine, and leucine, while ~40% comprised histidine, valine, isoleucine, leucine, methionine and threonine [100][219]. Further advances in metabolomics could improve theour understanding of various cellular metabolism networks and pathways related to SPC in legumes. Thus, integrating various ‘omics’ tools and emerging novel breeding approaches could assist in developing protein-fortified grain legumes (see Figure 1).