Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Peipei Wang and Version 4 by Jessie Wu.

Marine microorganisms, as important members of marine organisms, can produce numerous specific active substances in an extreme environment in low temperature, high salt, high pressure, and oligotrophic conditions. They have gained scientific interest due to their potential applications in the pharmaceutical, cosmetic and food industries, for environmental remediation, and astrobiology. The monosaccharide composition, high molecular weight, hydrophobicity and polycharged characteristics of marine Exopolysaccharides (EPS) are involved in their cryoprotective effect, water-holding capacity, and good thermostability. The source and structure of exopolysaccharides are summarized.

- exopolysaccharides

- microorganisms

- marine environment

1. The Source of Marine Exopolysaccharides PS

1.1. Exopolysaccharides Produced by General Marine Environmental Microorganisms

1.1. EPS Produced by General Marine Environmental Microorganisms

Among the several types of aquatic microorganisms, marine microorganisms account for half of the production of organic matter on earth [1][35]. Up to now, many common marine strains which can produce EPS were identified, such as Pseudoalteromonas species [2][3][15,36], Bacillus species [4][37], Alteromonas species [5][38], and the Vibrio species [6][39]. Several EPS with various structural features and biological activities have been isolated from those common marine strains, which are shown in Table 1 [7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50]. For example, an EPS, produced by a novel probiotic Pediococcus pentosaceus M41, was isolated from a marine source [7][40]. An exopolysaccharide EPS273 from marine bacterium P. stutzeri 273 could inhibit biofilm formation and disrupt the established biofilms of P. aeruginosa PAO1, indicating that EPS273 had a promising prospect in combating bacterial biofilm-associated infection [16][49]. A bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis RSK CAS4 was isolated from the ascidian Didemnum granulatum, in which the condition of producing EPS was optimized by the response surface method [9][42]. An EPS-producing strain FSW-25, assigned to the genus Microbacterium, was isolated from the Rasthakaadu beach, Kanyakumari, which could produce a large quantity of EPS [17][50]. Recently, a strain of Bacillus cereus was isolated from the Saudi Red Sea coast. EPSR3 was a major fraction of the EPS from this marine strain, which showed antioxidant, antitumor, and anti-inflammatory activities. These biological activities of EPSR3 may be attributed to its content of uronic acids [18][51].

Table 1.

Information of some EPS obtained from marine bacteria in the last decade.

| Source | Name | Preparation Method | Monosaccharides | Name Composition |

Mw (Da) | Preparation MethodBioactivity | References | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monosaccharides Composition | Mw (Da) | Bioactivity | References | ||||||||||||||||||

| Pantoea | sp. | YU16-S3 | EPS-S3 | Ethanol precipitation extraction and purification by Sephacryl S500-HR column |

Glc, Gal, GalNAc, GalN (1.9:1:0.4:0.02) |

1.75 × 10 | 5 | Promotion of Wound Healing | [19] | [34] | |||||||||||

| [ | 49 | ] | [ | 74 | ] | Pediococcus pentosaceus M41 | |||||||||||||||

| Porphyridium sordidum | EPS | Cold aqueous centrifugal extraction and purification by dialysis |

Fuc, Rha, Ara, Gal, Glc, Xyl, GlcA (1.93:0.36:0.36:48.28: 19.01:28.2:0.76) | Antibacterial | [67] | [24] | |||||||||||||||

| EPS-M41 | Aspergillus Terreus | Culture centrifugal extraction and purification by ultra-filtration | Ara, Man, Glc, Gal | YSS | Porphyridium marinum | EPS-0C,Culture centrifugal extraction and purification by QFF column | EPS-2C, EPS-5C Glc, Man |

Culture centrifugal extraction, ultra-filtration and High-Pressure Homogenizer(1.2:1.8:15.1:1.0) | (8.6:1.0) |

Xyl, Gal, Glc, Fuc, Ara, GlcA 6.8 × 10 | 5 | 1.86 × 10 | 4 | Antioxidant, |

Antioxidant | (44–47:25–29:19–20:1:1–2:4–5)Anticancer | 1.4 × 10 | 6 | 5.5 × 10 | 5[60] | [82] |

| 5.5 × 10 | 5 | Antibacterial, | Anti-biofilm, Anticancer | [7] | [40] | ||||||||||||||||

| [ | 68 | ] | [ | 95 | ] | Bacillus cereus KMS3-1 | EPS | Culture centrifugal extraction and purification by dialysis | Man, Glc, Xyl, Rha (73.51:17.87:2.18:6.49) |

Fusarium oxysporum | Waste-water treatment |

[ | Fw-1 | 8] | |||||||

| Flintiella | sanguinaria | [ | 41 | ] | |||||||||||||||||

| EPS | Oceanobacillus iheyensis | EPS | Ethanol precipitation and purification by dialysis |

Man, Glc, Ara (47.78:29.71:22.46) |

2.14 × 10 | 6 | Anti-biofilm | [ | |||||||||||||

| Ethanol precipitation, | anion-exchange and size exclusion chromatography | Man, Gal, Glc, (96.1, 3.3, and 0.60) |

2.25 × 10 | 4 | Anticancer | [66] | [88] |

Table 3. Information of some EPS obtained from marine microalgae and cyanobacteria in the last decade.

Table 3.

Information of some EPS obtained from marine microalgae and cyanobacteria in the last decade.

| Source | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture centrifugal extraction and purification by QFF column | ||||||||||||||||||

| Culture centrifugal extraction and purification by | Gal, Glc, Man | (1.33:1.33:1.00) | 6.12 × 10 | 4 | Antioxidant | ultra-filtration | [ | Xyl, Gal, GlcA, Rha, Glc, Ara (47:21:14:10:6:2) | 61] | [ | 1.5 × 10 | 6 | 83] | |||||

| [ | 69 | ] | [ | 96 | ] | 10] | [43] | |||||||||||

| Alternaria | sp. | AS2-1 | Culture centrifugal extraction and purification by QFF column | Man, Glc, Gal (1.00:0.67:0.35) |

2.74 × 10 | 4 | Anticancer, Antioxidant |

[62] | [84] | |||||||||

| Cyanothece | sp. CCY 0110 | Cyanoflan | Cold aqueous extraction and purification by dialysis |

Man, Glc, uronic acid, Gal, Xyl, Rha, Fuc, Ara (20:20:18:10:9:9:8:6) | >1 × 10 | 6 | [50] | [75] | Bacillus thuringiensis | RSK CAS4 | EPS | Culture centrifugal extraction and purification by Sepharose 4-LB Fast Flow column | Aspergillus versicolor | AWP | ||||

| Chlamydonas | Fuc, Gal, Xyl, Glc, Rha, Man | (43.8:20:17.8:7.2:7.1:4.1) |

Culture centrifugal extractionand purification by QFF column | reinhardtii | EPS | Culture centrifugal extractionGlc, Man (8.6:1.0)Antioxidant, Anticancer |

GalA, Rib, Rha, Ara, Gal, Glc, Xyl5 × 10 | 7[9] | [42] | |||||||||

| 2.25 × 10 | [ | 63 | ] | [ | 85] | |||||||||||||

| 5 | Antioxidant | [ | 70 | ] | [ | 97] | Pseudoalteromonas, MD12-642 | EPS | Culture centrifugal extraction and purification by ultra-filtration | GalA, GlcA, Rha, GlcN (41–42:25–26:16–22:12–16) |

>1.0 × 10 | 6 | [ | Aspergillus versicolor | LCJ-5-4 | Culture centrifugal extractionand purification by QFF column | Glc, Man (1.7:1.0) |

|

| Nostoc | carneum | 7 × 10 | EPS | 3 | Culture centrifugal Antioxidant |

extraction | Xyl, Glc (4.3:2.1) | 11] | [44] | |||||||||

| [ | 64 | ] | [ | Bacillus | sp. H5 | EPS5SH | Aqueous extraction and purification by GPC | Man, GlcN, Glc, Gal (1.00:0.02:0.07:0.02) |

8.9 × 10 | 4 | Immunomodulatory activity | [12] | [45] | |||||

| Alteromonas | sp. | JL2810 | EPS | Ethanol precipitation extraction and purification by DEAE column | GalA, Man, Rha (1:1:1) |

>1.67 × 10 | 5 | [13] | [46] | |||||||||

| 86 | ] | Pseudoalteromonas | sp. YU16-DR3A | EPS-DR3A | Culture centrifugal extraction and purification by dialysis | Fuc, Erythrotetrose, Glc, Rib (6.7:1.0:1.5:1.0) |

2 × 10 | 4 | Antioxidant | [14] | [47] | |||||||

| Enterobacter | sp. | ACD2 | EPS | Culture centrifugal extraction | Glc, Gal, Fuc, GlcA (25:25:40:10) |

Antibacterial | [15] | [48] | ||||||||||

| P. stutzeri | 273 | EPS273 | Culture centrifugal extraction and purification by GPC | GlcN, Rha, Glc (35.4:28.6:27.2) |

1.9 × 10 | 5 | Antibiofilm, Anti-Infection |

[16] | [49] | |||||||||

| Microbacterim | FSW-25 |

EPS Mi25 | Culture centrifugal extraction and purification by dialysis | Glc, Man, Fuc, GlcA | 7.0 × 10 | 6 | Antioxidant | [17] | [50] | |||||||||

| Bacillus cereus | EPSR3 | Culture centrifugal extraction | Glc, GalA, Arb (2.0: 0.8: 1.0) |

Antioxidant, Antitumor, Anti-inflammatory activities |

[18] | [51] | ||||||||||||

| Vibrio | sp. QY101 | A101 | Ethanol precipitation extraction and purification by GPC | GlcA, GalA, Rha, GlcN (21.47:23.05:23.90:12.15) |

5.46 × 10 | 3 | Antibacterial | [20] | [52] | |||||||||

| Halolactibacillus miurensis | EPS | Culture centrifugal extraction and purification by Sepharose 4-LB Fast Flow column | Gal, Glc (61.87:25.17) |

Antioxidant | [21] | [53] | ||||||||||||

| Halomonas saliphila | LCB169T | hsEPS | Ethanol precipitation, anion-exchange and gel-filtration chromatography | Man, Glc, Ara, Xyl, Gal, Fuc (81.22:15.83:1.47:0.59:0.55:0.35) |

5.133 × 10 | 4 | Emulsifying activity | [22] | [54] | |||||||||

| C.psychrerythraea 34H | EPS | Culture centrifugal extraction and purification by QFF column |

QuiN, GalA (1:2) |

Antifreeze | [23] | [26] | ||||||||||||

| Issachenkonii | SM20310 | Ethanol precipitation extraction and purification by DEAE column |

Rha, Xyl, Man, Gal, Glc, GalNAc, GlcNAc (2.1:0.9:71.7:9.0:10.7:1.5:4.0) |

>2.0 × 10 | 6 | Anti-freeze | [24] | [55] | ||||||||||

| Halomonas | sp. 2E1 | EPS2E1 | Culture centrifugal extraction and purification by DEAE column and Sephadex G75 column | Man, Glc (3.76:1) |

4.7 × 10 | 4 | Immunomodulatory activity | [25] | [56] | |||||||||

| Sphingobacterium | sp. | IITKGP-BTPF3 | Sphingobatan | Culture centrifugal extraction and purification by DEAE column | Man | >2 × 10 | 6 | Immunomodulatory activity | [26] | [57] | ||||||||

| Pseudoaltermonas | sp. | PEP | Culture centrifugal extraction and purification by dialysis and GPC | Glc, Gal, Man (4.8:50.9:44.3) |

3.97 × 10 | 5 | Anticancer | [27] | [58] | |||||||||

| Polaribacter | sp. | SM1127 EPS | Ethanol precipitation extraction and purification by Sepharose column | Rha, Fuc, GlcA, Man, Gal, Glc, GlcNAc (0.8:7.4:21.4:23.4:17.3:1.6:28.0) |

2.2 × 10 | 5 | Promotion of Wound Healing, Prevention of Frostbite Injury, Antioxidant |

[28][29] | [59,60] | |||||||||

| Aeribacillus pallidus 418 | EPS1, EPS2 |

Culture centrifugal extraction and purification by Sepharose DEAE CL-6B column | Man, Glc, GalN, GlcN, Gal, Rib (69.3:11.2:6.3:5.4:4.7:2.9); Man, Gal, Glc, GalN, GlcN, Rib, Ara (33.9:17.9:15.5:11.7:8.1:5.3:4.9) |

7 × 10 | 5 | ; >1 × 10 | 6 | [30] | [31] | |||||||||

| Rhodobacter johrii CDR-SL 7Cii | EPS RH-7 | Ethanol precipitation and purification by dialysis | Glc, GlcA, Rha, Gal (3:1.5:0.25:0.25) |

2 × 10 | 6 | Emulsifying activity |

[31] | [61] | ||||||||||

| Alteromonas ininus | GY785 | Culture centrifugal extraction and purification by ultra-filtration |

Rha, Fuc, Man, Gal, Glc, GalA, GlcA (0.2:0.1:0.4: 3.6:4.7:1.0:2.0) |

2.0 × 10 | 6 | [32][33] | [62,63] |

Moreover, the halophilic bacteria are known to produce EPS for withstanding the osmotic pressure. However, due to their ubiquitous distribution in saline environments, the exploration for biologically active novel EPS from halophilic bacteria is in its early stages. A bacterial EPS, named as A101 from the strain Vibrio sp.QY101, had antibiofilm activity [20][52]. An EPS named as HMEPS was first isolated from Halolactibacillus miurensis and had good antioxidant activity [21][53]. A novel EPS, designated hsEPS, was successfully isolated from the high-salt fermented broth of a novel species, Halomonas saliphila LCB169T. The structural of hsEPS was well-characterized as having a major backbone composed of (1→2)-linked α-D-Manp and (1→6)-linked α-D-Manp, with branches substituted at C-2 by T-α-D-Manp and at C-6 by the fragment of T-α-D-Manp-(1→2)-α-D-Manp-(1→ [22][54].

1.2. Exopolysaccharides Produced by Polar Microorganisms

1.2. EPS Produced by Polar Microorganisms

Most microorganisms in the deep-sea and polar environment are affected by low temperatures and poor nutrition [34][64]. For the microorganisms living in a cold environment, it has been shown that their cells are almost surrounded by EPS [35][5]. The ability of organisms to survive and grow in a low-temperature environment depends on a series of adaptive strategies, including membrane structure modification. To understand the role of the membrane in adaptation, it is necessary to determine the cell wall components that represent the main components of the outer membrane, such as EPS. Studies have indicated that the secreted EPS with negatively charged residues, such as sulfate and carboxylic groups, allowed them to form hydrated viscous three-dimensional networks that confer adhesive and barrier properties against freezing temperatures [36][1]. For example, Ornella Carrión et al. isolated Pseudomonas ID1 from the marine sediment samples of Antarctica. The EPS produced by this strain showed significant protection against the cold [37][65]. The Pseudomonas sp. BGI-2 isolated from the glacier ice sample could produce high amounts of EPS, which had cryoprotective activity [38][66]. The produce condition of EPS from a cold-adapted marinobacter, namely as W1-16, was optimized by evaluating the influences of the carbon source, temperature, pH and salinity. The monosaccharide composition of this EPS resulted in Glc:Man:Gal:GalN:GalA:GlcA, with a relative molar ratio of 1:0.9:0.2:0.1:0.1:0.01 [39][67]. Now, several EPS isolated from psychrophilic bacteria in the Arctic and Antarctic marine environment have been reported, which have a potential application in the cryopreservation, food, and biomedical industries [23][24][25][26][27][28][29][40][21,26,55,56,57,58,59,60]. The source, structural, and biological information of these EPS are shown in Table 1.

1.3. Exopolysaccharides from Marine Hot Spring Microorganisms

2.3. EPS from Marine Hot Spring Microorganisms

Over the past decade, lots of microbes from marine hot springs have been reported, most of which produce special EPS to protect themselves from extreme conditions. These thermophilic microorganisms are classified as thermophiles growing at 55 °C~80 °C and hyperthermophiles growing above 80 °C. The thermophilic microorganisms contain multiple genera, such as Aeribacillus, Anoxybacillus, Brevibacillus, and Geobacillus [30][31]. The EPS produced by thermophilic bacteria usually have a high molecular weight with good emulsifying properties, leading to great potential application in the food and cosmetics industries [31][32][33][41][42][19,28,61,62,63]. Four thermophilic aerobic Bacillus isolated from Bulgarian hot springs are reported by Radchenkova et al., which are Aeribacillus pallidus, Geobacillus toebii, Brevibacillus thermoruber, and Anoxybacillus kestanbolensis. These bacteria can all produce EPS. After optimizing the culture conditions of the Aeribacillus pallidus strain 418, the output of EPS1 and EPS2 has more than doubled [30][31]. A novel exopolysaccharide RH-7 with a high molecular weight of 2000 kDa was produced by this marine bacterial strain assigned to the genus Rhodobacter from the surface of the marine macroalgae (Padina sp.). This EPS showed high-temperature resistance and could act as a bio-emulsifier to create a high pH and temperature-stable emulsion of hydrocarbon/water [31][61].

2. The Structural Characteristics of Marine ExopolysaccharidesPS

2.1. Structural Characterization Methods of Marine Microbial Exopolysaccharides

2.1. Structural Characterization Methods of Marine Microbial EPS

The marine microbial EPS have high structural diversity and complexity. To evaluate their structure, the monosaccharide composition, molecular weight, and glycosidic linkage need to be determined. Before the structural analysis, a homogeneous EPS should be obtained to remove the influence of other salt, pigment, and protein impurities. At present, the commonly used purification methods of EPS include ethanol precipitation, ultrafiltration, ion-exchange chromatography, and gel chromatography. The methods of SDS-PAGE and DOC-PAGE with Alcian blue staining are very useful to detect the presence of EPS [43][68]. The monosaccharide composition of EPS has been determined by a variety of methods, including acid hydrolysis followed by appropriate derivatization and gas chromatography (GC); pre-column derivatization with high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC); and high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection (HPAEC-PAD) [44][45][69,70]. The molecular weight can be determined by high-performance gel-permeation chromatography (HPGPC), combined with differential detector (ID) or multi-angle laser light scattering (MALS) [46][71]. Furthermore, through the data of the Fourier-Transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), methylation analysis, and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), the glycosidic bond-linking types and main functional groups can be obtained [23][47][48][49][26,72,73,74].

Besides these classical chemical procedures, new and powerful tools, such as zeta potential and particle-size analyzer, attenuated total reflectance Fourier-Transform infra-red spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR), differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), scanning electron microscope (SEM), atomic force microscopy (AFM), circular dichroism spectrum (CD), small-angle neutron scattering (SANS), and X-ray diffraction (XRD) techniques have been applied to investigate the surface morphology and physical properties of EPS [7][8][42][50][51][52][53][28,40,41,75,76,77,78]. For example, the physicochemical properties and rheological properties of an EPS-M41, produced by a novel probiotic Pediococcus pentosaceus M41 isolated from a marine source, were evaluated in detail. The average molecular weight of this EPS was determined to be 682.07 kDa by HPGPC method. The EPS-M41 consisted of Ara, Man, Glc, and Gal with a molar ratio of 1.2:1.8:15.1:1.0 by the GC method. The structure of the EPS-M41 was proposed as →3) α-D-Glc (1→2) β-D-Man (1→2) α-D-Glc (1→6) α-D-Glc (1→4) α-D-Glc (1→4) α-D-Gal (1→), with Ara linked at the terminals by FTIR and NMR analysis. The SEM analysis showed that the EPS-M41 possessed a unique compact, stiff and layer-like structure. The particle and zeta charges analyses exhibited that the EPS-M41 had a size diameter of 446.8 nm and a zeta potential of -176.54 mV. The DSC thermogram exhibited that the EPS-M41 had a higher melting point, indicating its resistance to the thermal processes [7][40]. Another example, the ATR-FTIR technique, was used to observe the movement of the -SH, -PO4, and -NH functional groups in the EPS from Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes NP103, and confirmed their involvement in the Pb (II) binding. The results emphasized the potential importance of P. pseudoalcaligenes NP103 EPS as a biosorbent for the removal of Pb (II) from the contaminated sites [42][28].

2.2. Examples of Marine Microbial Exopolysaccharides in the Last Decade

2.2. Examples of Marine Microbial EPS in the Last Decade

Several reviews have summarized the culture and fermentation conditions, distribution, biosynthesis, and biotechnological production of microbial EPS from marine sources [36][40][41][54][55][56][57][58][59][1,12,14,19,20,21,79,80,81]. In the past decade, with the development of separation and identification technology, numbers of new marine microorganisms have been identified. By optimizing the culture conditions, novel EPS with new biological activities have been discovered. Here, a variety of EPS obtained from marine microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and microalgae, in the last decade are summarized in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3. It will give peopleus more useful information of the structure–activity relationship of the marine EPS through the analysis of their origin, monosaccharide composition, molecular weight, and bioactivities.

Table 2.

Information of some EPS obtained from marine fungi in the last decade.

| Source | Name | Preparation Method | Monosaccharides Composition |

Mw (Da) | Bioactivity | References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aureobasidium | melanogenum | SCAU-266 |

AUM-1 | Alcohol precipitation and further purified through DEAE-column | Glc, Man, Gal (97.30:1.9:0.08) |

6.0 × 10 | 3 | Immunomodulatory activity | |

| Antioxidant | |||||||||

| [ | 71 | ] | [ | 93 | ] | ||||

| Penicillium solitum | GW-12 | Ethanol precipitation, anion-exchange and size exclusion chromatography |

Man | 1.13 × 10 | 4 | ||||

| Nostoc | sp. | EPS | Culture centrifugal extraction and purification by DEAE column | Uronic acid, Rha, Fuc, Ara, Xyl, Man, Gal, Glc (25.0:0.2:0.8:18.6:15.3:19.1:1.3:19.7) |

2.37 × 10 | [65] | [87] | ||

| 5 | Antitussive, Immunomodulatory activity | [ | 72 | ] | [ | 73] | [98,99] | Hansfordia sinuosae | HPA |

| Tetraselmis suecica | EPS | Cold aqueous extractionand purification by dialysis | Ara, Rib, Man, GalA, Gal, Glc, GlcA (5.23:0.83:6.64:0.1:25.27:35.46:21.47) | Antioxidant, Anticancer | [74] | [94] | |||

| Leptolyngbya | sp. | EPS | Culture centrifugal extraction |

Man, Ara, Glc, Rha, uronic acid (35:24:15:2:8) | Antioxidant | [75] | [100] |

The examples of EPS obtained from marine bacteria in the last decade are shown in Table 1. The marine microbial EPS are complex, and large polymers, usually composed of more than one monosaccharide, including pentoses, hexoses, amino sugars, and uronic acids. More commonly, they attach to proteins, lipids, or non-carbohydrate metabolites, such as pyruvate, sulphate, acetate, phosphates, and succinate, as their additional structural components, which increased their structural diversity and complexity [76][13]. Some of the monosaccharides, such as fucose, ribose, uronic acid and aminosaccharides, which are not common in plant polysaccharides, are widely found in the marine bacterial EPS. These special monosaccharides present are also closely related to the biological functions of these marine bacterial EPS. For instance, the structure of a novel EPS isolated from Colwellia psychrerythraea 34H was fullly characterized to have a repeating unit, composed of a N-acetyl-quinovosamine (QuiN) unit and two galacturonic acid residues both decorated with alanine amino acids, which had a significant cryoprotective effect. By NMR and computational analysis, the pseudo-helicoidal structure of this EPS may block the local tetrahedral order of the water molecules in the first hydration shell, and could inhibit the ice recrystallization [23][26]. A novel anionic EPS, named as FSW-25, was produced by marine Microbacterium aurantiacum. FSW-25 was a high molecular-weight heteropolysaccharide with a high uronic acid content. It had good antioxidant potential when compared with xanthan, which might be due to the presence of sulphate and its higher uronic content [17][50]. In addition, the monosaccharide composition of the EPS and other residues could play an essential role in thermostability. For example, the high thermal stability of EPS1-T14 produced by Bacillus licheniformis was mainly attributed to the fucose content [42][77][28,29]. The role of the monosaccharides’ composition in the thermal stability of the marine bacteria EPS has to be further investigated.

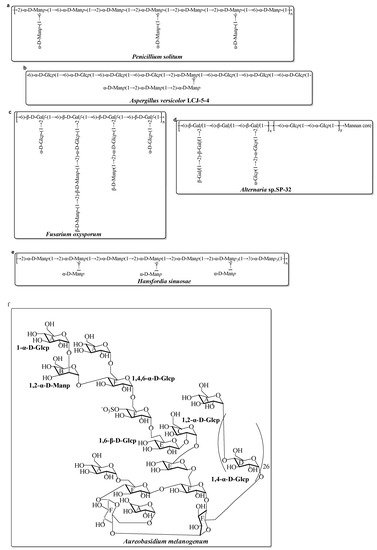

Compared with the diversity and complexity of the marine bacteria EPS, these EPS isolated from marine fungi exhibit less significant diversity in the monosaccharide composition (Table 2). The monosaccharide compositions show that these marine fungal EPS are mainly composed of neutral monosaccharide, including Glc, Man, and Gal with a different molar ratio. Generally, these EPS have antioxidant activity. Mao et al. completed relatively systematic studies on the structure and activity screening of marine fungal EPS. Several of the EPS are isolated and fullly characterized from Aspergillus versicolor, Aspergillus Terreus, Fusarium oxysporum, and Hansfordia sinuosae (Table 2). Recently, a novel EPS (AUM-1) with immunomodulatory activity was obtained from the marine Aureobasidium melanogenum SCAU-266. The AUM-1 with a molecular weight of 8000 Da had a main monosaccharide of Glc (97.30%), whose structure possessed a potential backbone of α-D-Glcp-(1→2)-α-D-Manp-(1→4)-α-D-Glcp-(1→6)-(-(SO3−)-4-α-D-Glcp-(1→6)-1-β-D-Glcp-1→2)-α-D-Glcp-(1→6)-β-D-Glcp-1→6)-α-D-Glcp-1→4)-α-D-Glcp-6→1)-[α-D-Glcp-4]26→1)-α-D-Glcp [49][74]. The possible structure of these marine fungal EPS mentioned in Table 2 are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Structures of several EPS, isolated from marine fungi in the last decade [49][61][62][63][64][65][66][74,83,84,85,86,87,88]. (a) EPS from Penicillium solitum; (b) EPS from Aspergillus versicolor; (c) EPS from Fusarium oxysporum; (d) EPS from Alternaria sp.; (e) EPS from Hansfordia sinuosae; (f) EPS from Aureobasidium melanogenum.

Besides the marine bacteria and fungi, marine microalgae and cyanobacteria are other important resources to produce EPS. Information of some of the EPS obtained from marine microalgae and cyanobacteria in the last decade are shown in Table 3. These EPS usually have a complex monosaccharide composition with uronic acid and sulfate groups, with various biological activities such as antioxidant, antiviral, antifungal, antibacterial, anti-ageing, anticancer, and immunomodulatory activities [78][79][89,90]. Recently, Esqueda et al. systematically explored the diversity of 11 microalgae strains belonging to the proteorhodophytina subphylum for EPS production. Regarding the compositions, some of the common features were highlighted, such as the presence of Xyl, Gal, Glc, and GlcA in all of the compositions, but with different amounts depending on the samples. In addition, the existence of sulfate groups in EPS from those microalgae strains were much more different [80][91]. The EPS from Chlorella sorokiniana had anticoagulant and antioxidant activities. The sulfate content and their binding site, monosaccharide composition, and glycoside bond were involved in its bioactivity [81][92]. Cyanoflan, a cyanobacterial-sulfated EPS, was characterized in terms of its morphology, structural composition, and rheological and emulsifying properties. The glycosidic linkage analysis revealed that this EPS had a highly branched complex structure with a large number of sugar residues, including Man, Glc, uronic acids, Gal, Rha, Xyl, Fuc, and Ara with a molar ratio of 20:20:18:10:9:9:8:6. The high molecular weight (>1 MDa) and entangled structure was consistent with its high apparent viscosity in aqueous solutions and high emulsifying activity [50][75]. The EPS from the cyanobacterium Nostoc carneum was a type of polyanionic polysaccharide that contained uronic acid and sulfate groups [71][93]. Another EPS from Tetraselmis suecica (Kylin) with antioxidant and anticancer activities also had a high amount of uronic acid [74][94]. The acid groups played important roles in the antioxidant activity of the marine EPS.