Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) is one of the most frequently-found mycotoxins in contaminated food. As the content of mycotoxins is particularly low in food, the development of probes to detect AFB1 in foods with high sensitivity and selectivity is an urgent social need for the evaluation of food quality. Numerous techniques have been developed to monitor AFB1. Nevertheless, most of them require cumbersome, labor-consuming, and sophisticated instruments, which have limited their application. An aptamer is a single, short nucleic acid sequence that is capable of recognizing different targets. Owing to their unique properties, aptamers have been considered as alternatives to antibodies. Aptasensors are considered to be an emerging strategy for the quantification of aflatoxin B1 with high selectivity and sensitivity.

- Aflatoxin B1

- Aptamer

- Detection

Please note: Below is an entry draft based on your previous paper, which is wrirren tightly around the entry title. Since it may not be very comprehensive, we kindly invite you to modify it (both title and content can be replaced) according to your extensive expertise. We believe this entry would be beneficial to generate more views for your work. In addition, no worry about the entry format, we will correct it and add references after the entry is online (you can also send a word file to us, and we will help you with submitting).

Definition

Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) is one of the most frequently-found mycotoxins in contaminated food. As the content of mycotoxins is particularly low in food, the development of probes to detect AFB1 in foods with high sensitivity and selectivity is an urgent social need for the evaluation of food quality. Numerous techniques have been developed to monitor AFB1. Nevertheless, most of them require cumbersome, labor-consuming, and sophisticated instruments, which have limited their application. An aptamer is a single, short nucleic acid sequence that is capable of recognizing different targets. Owing to their unique properties, aptamers have been considered as alternatives to antibodies. Aptasensors are considered to be an emerging strategy for the quantification of aflatoxin B1 with high selectivity and sensitivity.

1. Introduction

Mycotoxins are a class of secondary metabolites produced by molds that are widely distributed in nature and are highly common in food contamination [1]. When humans and animals take in mycotoxins through food, they can cause a decline in body function, which can lead to illness or death [2]. Common mycotoxins are ochratoxins, fumonisins, aflatoxins, citrinin (CTN), and zeallenone (ZEN) [3]. Among them, aflatoxin (AF) is a kind of highly-toxic secondary metabolite produced by the fungi Aspergillus flavus, as well as Aspergillus parasiticus. It has been reported that aflatoxin is a highly stable natural mycotoxin [4]. Aflatoxins show strong heap-toxicity after entering human or animal bodies, which can cause liver hemorrhage, steatosis, bile duct hyperplasia, and liver cancer [5]. People and animals mainly ingest aflatoxins through dietary channels. With the occurrence of aflatoxin contamination, the pollution of aflatoxin in food has gained attention in countries all over the world. The detection of aflatoxin in food has become a hot subject for scholars at home and abroad. Among various aflatoxins, AFB1 is the most common and toxic, owing to its capacity to forbid the RNA synthesis of cells, which can largely increase the risk of liver cirrhosis, necrosis, and carcinoma in human beings and animals. The cancer research organization of the World Health Organization has classified it as a Class I carcinogen.

A large number of technologies have been developed for the quantification of AFB1, such as high-performance liquid chromatography [6[6][7],7], liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry [8,9][8][9], and thin-layer chromatography [10]. Although these methods are very mature, they are hindered by cumbersome operations, long detection cycles, complicated sample pre-processing, rapid screening for large numbers of samples, expensive instruments, and inconvenient portability, which limit their detection ability in practical applications [11]. In recent years, methods for detecting aflatoxins based on antibody-linked immunosorbent assays have been developed, to some extent. However, these methods, which use antibodies as recognition molecules, are expensive, unstable, and prone to false-positive detection results [12]. Therefore, it is particularly urgent and important to develop low-cost, high-sensitivity methods for the detection of aflatoxins in actual samples, such as foods and related products.

With the recent developments in biotechnology, a biomolecule—called a nucleic acid aptamer (aptamer)—has been widely used in biosensors. Aptamer is a nucleic acid ligand and, furthermore, it is an index-enriched ligand. Aptamer is a nucleic acid ligand that was exponentially enriched by the phylogenetic technique. The phylogenetic technique SELEX screens a single-stranded oligonucleotide in vitro to specifically bind small molecules, proteins, bacteria, viruses, cells, and the like [12,13][12][13]. In the field of analysis and diagnosis, nucleic acid aptamers have many advantages (compared with traditional antibodies), including convenient preparation, specificity, stability, ease of modification, strong affinity, and wide range of target molecules [14,15][14][15]. As an emerging biomarker probe and recognition molecule, it is widely used in the construction of biosensors, and its application in disease diagnosis and treatment, proteomics research, biosensing and toxin sensing, microbial detection, and other fields [16,17][16][17]. With the continuous improvement and combination of nucleic acid aptamers, rapid biotoxin detection technologies will be more portable, more stable, and more efficient, giving great advantages.

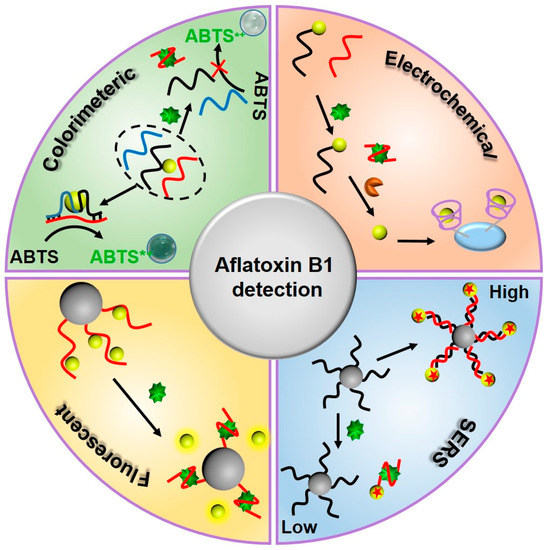

As an oligonucleotide fragment, a nucleic acid aptamer does not have a signal transduction function. Its recognition and binding process, specific to a target molecule, does not produce a detectable physicochemical signal. Therefore, there is a need for a process to convert the specific recognition-binding process of a nucleic acid aptamer to a target substance into a readily-detectable optical signal change. As shown in Figure 1, this review focuses on the application of nucleic acid aptamer sensors in AFB1 detection, based on colorimetric, electrochemical, fluorescent, and surface-enhanced Raman scattering aptamer sensors, in recent decades.

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of detection strategies for aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) by utilizing AFB1 aptamer sensors.

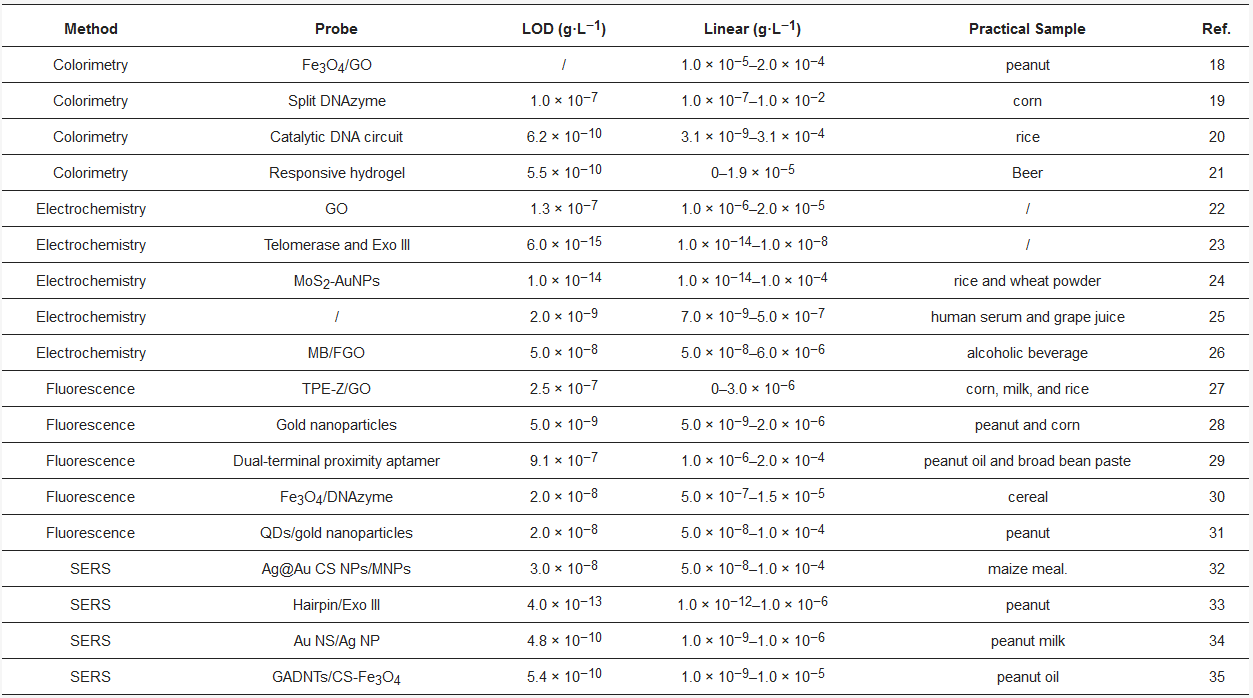

2. Summary

A variety of classical strategies have been employed for the detection of AFB1; however, their drawbacks, including time consumption, expensive equipment, and low portability, have limited their further use. On account of the high selectivity of aptamers toward specific targets, aptamers can be used to replace antibodies for the quantification of analytes. In this review, we described various aptamer probes for the detection of AFB1. As listed in Table 1, the probes consist of colorimetric, electrochemical, and fluorescent methods. The probes utilize colorimetric, electrochemical, and fluorescent methods. Although great breakthroughs have been made, the stability of aptamer probes should be improved by the modification of DNA. Moreover, aptamer probes associated with signal amplification strategies can be employed to improve the sensitivity of the probe.

Table 1. Comparison of different strategies for AFB1 detection. Reference: [18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35]

References

- Robbins, C.A.; Swenson, L.J.; Nealley, M.L.; Kelman, B.J.; Gots, R.E. Health effects of mycotoxins in indoor air: A critical review. Appl. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2000, 15, 773–784.

- Hussein, H.S.; Brasel, J.M. Toxicity, metabolism, and impact of mycotoxins on humans and animals. Toxicology 2001, 167, 101–134.

- Chauhan, R.; Singh, J.; Sachdev, T.; Basu, T.; Malhotra, B. Recent advances in mycotoxins detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 81, 532–545.

- Pietri, A.; Fortunati, P.; Mulazzi, A.; Bertuzzi, T. Enzyme-assisted extraction for the HPLC determination of aflatoxin M1 in cheese. Food Chem. 2016, 192, 235–241.

- Mishra, N.; TandonnVL, D.K.; Khandia, R.; Munjal, A. Does Bougainvillea spectabilis protect swiss albino mice from aflatoxin-induced hepa-totoxicity. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2016, 4, 250–257.

- Huertas-Pérez, J.F.; Arroyo-Manzanares, N.; Hitzler, D.; Castro-Guerrero, F.G.; Gámiz-Gracia, L.; García-Campaña, A.M. Simple determination of aflatoxins in rice by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography coupled to chemical post-column derivatization and fluorescence detection. Food Chem. 2018, 245, 189–195.

- Zhao, J.; Zhu, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Ning, J.; Yang, Y. Ionic-liquid-based dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction combined with magnetic solid-phase extraction for the determination of aflatoxins B1, B2, G1, and G2 in animal feeds by high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection. J. Sep. Sci. 2016, 39, 3789–3797.

- Di Gregorio, M.C.; Jager, A.V.; Costa, A.A.; Bordin, K.; Rottinhghaus, G.E.; Petta, T.; Souto, P.C.; Budiño, F.E.; Oliveira, C.A. Determination of aflatoxin B1-lysine in pig serum and plasma by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2017, 41, 236–241.

- Miró-Abella, E.; Herrero, P.; Canela, N.; Arola, L.; Borrull, F.; Ras, R.; Fontanals, N. Determination of mycotoxins in plant-based beverages using QuEChERS and liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 2017, 229, 366–372.

- Qu, L.-L.; Jia, Q.; Liu, C.; Wang, W.; Duan, L.; Yang, G.; Han, C.-Q.; Li, H. Thin layer chromatography combined with surface-enhanced raman spectroscopy for rapid sensing aflatoxins. J. Chromatogr. A 2018, 1579, 115–120.

- Raeisossadati, M.J.; Danesh, N.M.; Borna, F.; Gholamzad, M.; Ramezani, M.; Abnous, K.; Taghdisi, S.M. Lateral flow based immunobiosensors for detection of food contaminants. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 86, 235–246.

- Tuerk, C.; Gold, L. Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science 1990, 249, 505–510.

- Ellington, A.D.; Szostak, J.W. Invitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands I. Nature 1990, 346, 818–822.

- Sefah, K.; Phillips, J.A.; Xiong, X.; Meng, L.; Van Simaeys, D.; Chen, H.; Martin, J.; Tan, W. Nucleic acid aptamers for biosensors and bio-analytical applications. Analyst 2009, 134, 1765–1775.

- Qiu, L.; Wimmers, F.; Weiden, J.; Heus, H.A.; Tel, J.; Figdor, C.G. A membrane-anchored aptamer sensor for probing IFNγ secretion by single cells. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 8066–8069.

- Kikuchi, N.; Reed, A.; Gerasimova, Y.V.; Kolpashchikov, D.M. Split Dapoxyl Aptamer for Sequence-Selective Analysis of Nucleic Acid Sequence Based Amplification Amplicons. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 2667–2671.

- Niu, J.X.; Hu, X.M.; Ouyang, W.; Chen, Y.; Liu, S.W.; Han, J.; Liu, L.H. Femtomolar detection of lipopolysaccharide in injectables and serum samples using aptamer-coupled reduced graphene oxide in a continuous injection-electrostacking biochip. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 2360–2367.

- Hao, N.; Lu, J.; Zhou, Z.; Hua, R.; Wang, K. A pH-resolved colorimetric biosensor for simultaneous multiple target detection. ACS Sens. 2018, 3, 2159–2165.

- Seok, Y.; Byun, J.-Y.; Shim, W.-B.; Kim, M.-G. A structure-switchable aptasensor for aflatoxin B1 detection based on assembly of an aptamer/split DNAzyme. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 886, 182–187.

- Chen, J.; Wen, J.; Zhuang, L.; Zhou, S. An enzyme-free catalytic DNA circuit for amplified detection of aflatoxin B1 using gold nanoparticles as colorimetric indicators. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 9791–9797.

- Ma, Y.; Mao, Y.; Huang, D.; He, Z.; Yan, J.; Tian, T.; Shi, Y.; Song, Y.; Li, X.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Portable visual quantitative detection of aflatoxin B-1 using a target-responsive hydrogel and a distance-readout microfluidic chip. Lab Chip 2016, 16, 3097–3104.

- Mo, R.; He, L.; Yan, X.; Su, T.; Zhou, C.; Wang, Z.; Hong, P.; Sun, S.; Li, C. A novel aflatoxin B1 biosensor based on a porous anodized alumina membrane modified with graphene oxide and an aflatoxin B1 aptamer. Electrochem. Commun. 2018, 95, 9–13.

- Zheng, W.; Teng, J.; Cheng, L.; Ye, Y.; Pan, D.; Wu, J.; Xue, F.; Liu, G.; Chen, W. Hetero-enzyme-based two-round signal amplification strategy for trace detection of aflatoxin B1 using an electrochemical aptasensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 80, 574–581.

- Peng, G.; Li, X.; Cui, F.; Qiu, Q.; Chen, X.; Huang, H. Aflatoxin B1 electrochemical aptasensor based on tetrahedral DNA nanostructures functionalized three dimensionally ordered macroporous MoS2–AuNPs film. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 17551–17559.

- Abnous, K.; Danesh, N.M.; Alibolandi, M.; Ramezani, M.; Emrani, A.S.; Zolfaghari, R.; Taghdisi, S.M. A new amplified π-shape electrochemical aptasensor for ultrasensitive detection of aflatoxin B1. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 94, 374–379.

- Goud, K.Y.; Hayat, A.; Catanante, G.; Satyanarayana, M.; Gobi, K.V.; Marty, J.L. An electrochemical aptasensor based on functionalized graphene oxide assisted electrocatalytic signal amplification of methylene blue for aflatoxin B1 detection. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 244, 96–103.

- Jia, Y.; Wu, F.; Liu, P.; Zhou, G.; Yu, B.; Lou, X.; Xia, F. A label-free fluorescent aptasensor for the detection of Aflatoxin B1 in food samples using AIEgens and graphene oxide. Talanta 2019, 198, 71–77.

- Wang, B.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Weng, B.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Z.; Li, C.M.; Yu, C. Aptamer induced assembly of fluorescent nitrogen-doped carbon dots on gold nanoparticles for sensitive detection of AFB1. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 78, 23–30.

- Xia, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, H.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, K.; Lu, Y.; Deng, R.; He, Q. Enzyme-free amplified and ultrafast detection of aflatoxin B1 using dual-terminal proximity aptamer probes. Food Chem. 2019, 283, 32–38.

- Wang, L.; Zhu, F.; Chen, M.; Zhu, Y.; Xiao, J.; Yang, H.; Chen, X. Rapid and visual detection of aflatoxin B1 in foodstuffs using aptamer/G-quadruplex DNAzyme probe with low background noise. Food Chem. 2019, 271, 581–587.

- Lu, X.; Wang, C.; Qian, J.; Ren, C.; An, K.; Wang, K. Target-driven switch-on fluorescence aptasensor for trace aflatoxin B1 determination based on highly fluorescent ternary CdZnTe quantum dots. Anal. Chim. Acta 2019, 1047, 163–171.

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, M.; Song, Q. Double detection of mycotoxins based on SERS labels embedded Ag@ Au core–shell nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interface 2015, 7, 21780–21786.

- Li, Q.; Lu, Z.; Tan, X.; Xiao, X.; Wang, P.; Wu, L.; Shao, K.; Yin, W.; Han, H. Ultrasensitive detection of aflatoxin B1 by SERS aptasensor based on exonuclease-assisted recycling amplification. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 97, 59–64.

- Li, A.; Tang, L.; Song, D.; Song, S.; Ma, W.; Xu, L.; Kuang, H.; Wu, X.; Liu, L.; Chen, X. A SERS-active sensor based on heterogeneous gold nanostar core–silver nanoparticle satellite assemblies for ultrasensitive detection of aflatoxinB1. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 1873–1878.

- Yang, M.; Liu, G.; Mehedi, H.M.; Ouyang, Q.; Chen, Q. A universal sers aptasensor based on DTNB labeled GNTs/Ag core-shell nanotriangle and CS-Fe3O4 magnetic-bead trace detection of Aflatoxin B1. Anal. Chim. Acta 2017, 986, 122–130.