You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Rita Xu and Version 3 by Rita Xu.

Palmoplantar pustulosis (PPP) is a disease that causes recurrent blisters and aseptic pustules on the palms and soles. It has been suggested that both innate and acquired immunity are involved. In particular, based on the tonsils and basic experiments, it has been assumed that T and B cells are involved in its pathogenesis. In addition, the results of clinical trials have suggested that IL-23 is closely related to the pathogenesis.

- palmoplantar pustulosis

- B cells

- T cells

- IL-23

1. Introduction

Palmoplantar pustulosis (PPP) is a disease that causes recurrent blisters and aseptic pustules on the palms and soles. Pustules are caused by the accumulation of neutrophils (a type of white blood cell), which are involved in the inflammatory response, beneath the stratum corneum, the top layer of the skin. The rash begins as small blisters (bullae) that gradually turn into pustules. Later, scabs (crusts) form and the stratum corneum (thin layer on the top surface of the skin) peels off. Later, the rash becomes a mixture of these lesions. At the beginning, the rash often itches. There are no bacteria (germs) or fungi (molds) in the ooze of this skin disease. Therefore, there is no infection from the hands and feet to other parts of the body. Thus far, the cause of PPP is unknown, but rwesearchers will summarize the basic findings known to date.

2. PPP and Molecular Genetic Background

2.1. Familial Onset Is Rare, but Genetic Risk Factors Are Presumed

There are few reports of familial onset of PPP [1][2]. Yanai et al. performed human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing within a family with PPP and reported that 4 out of 6 family members with PPP had haplotypes A2, B46, Cw1, DR8, and DQ1 [1]. Matsuoka et al. reported two families with PPP and psoriasis vulgaris (PsV) in the family [2]. In one family, the grandmother had PPP, and the mother and daughter had PPP and PsV, and both had A2, B35, Cw3 DRw8, and DRw52 haplotypes. In another family, where a mother had PPP and PsV and a son had PPP, both had haplotypes of A26, Bw60, DRw9, and DRw53. PPP has also been reported from Japan with IL36RN (Interleukin 36 Receptor Antagonist) gene mutation [3] and CARD14 (Caspase recruitment domein-containing protein 14) gene mutation [4]. CARD14 mutations are also considered a risk factor in Europe [5]. However, there might be other genetic risk factors that have not yet been identified.2.2. Involvement of Cytokines

Mutations in IL19, IL20, and IL24 have been reported as risk factors for PPP [6][7][8]. Missense mutations in the CARD14 gene have been reported in PPP. Recently, mutations in AP1S3 (Adaptor Related Protein Complex 1 Subunit Sigma 3) were reported. ATG16L1 (Autophagy Related 16-like 1) mutation was also detected in PPP [9]. ATG16L1 is an essential gene for autophagy. These mutations are involved in the production of antimicrobial peptides, IL-18, and IL-1. Loss-of-function mutations in IL-36RN activate the IL-36 signaling pathway, resulting in excessive cytokine production [9], which is also seen in PPP, albeit at a lower frequency [10]. In addition to environmental factors and genetic susceptibility, both innate and acquired immunity are involved in the pathogenesis of PPP. Inflammation of sweat glands within the epidermis forms blisters and pustules [11]. IL-17 expression is increased in eccrine sweat glands, suggesting that this site is important in the pathogenesis [12]. It has been suggested that IL-8 (neutrophil chemoattractant), IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-17A, IL-17C, IL-17D, IL-17F, IL-22, IL-23A, and IL-23 receptor are elevated in the lesions of PPP [13][14][15]. Increased serum levels of TNF-α, IL-17, IL-22, and IFN-γ have been detected in patients with PPP [13][14][15]. Elevated expression of IL-17, IL-8, and IL-36γ has been reported in sweat glands. Tonsil infection triggers PPP [16].3. Factors involved in the Onset and Exacerbation of Disease and Its Relation to the Molecular Mechanism

Smoking, focal infections such as asymptomatic tonsillitis and asymptomatic periodontitis, severe constipation and irritable bowel syndrome, metal allergies, as well as stress are involved in the development of PPP. In treating PPP, it is necessary to be properly informed about its relationship to smoking cessation, to focal infection, and to metal allergy. In this section, the relationship of PPP to smoking, focal infection, and metal allergy will be discussed in detail.3.1. PPP and Smoking

Smoking rates in PPP patients are very high, at about 80%. Smoking cessation tends to reduce symptoms [17] and improve treatment efficacy [18][19]. Possible mechanisms include direct stimulation of the tonsils by smoking which increases the production of inflammatory substances (such as interleukin (IL)-17), induces or aggravates inflammation in the tonsils, aggravates other factors such as periodontitis, alters immune responses to commensal bacteria, and activates cholinergic signaling pathways through the production of Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α from epidermal cells and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.3.2. PPP and Focal Infection (e.g., Lesional Tonsils, Dental Lesions)

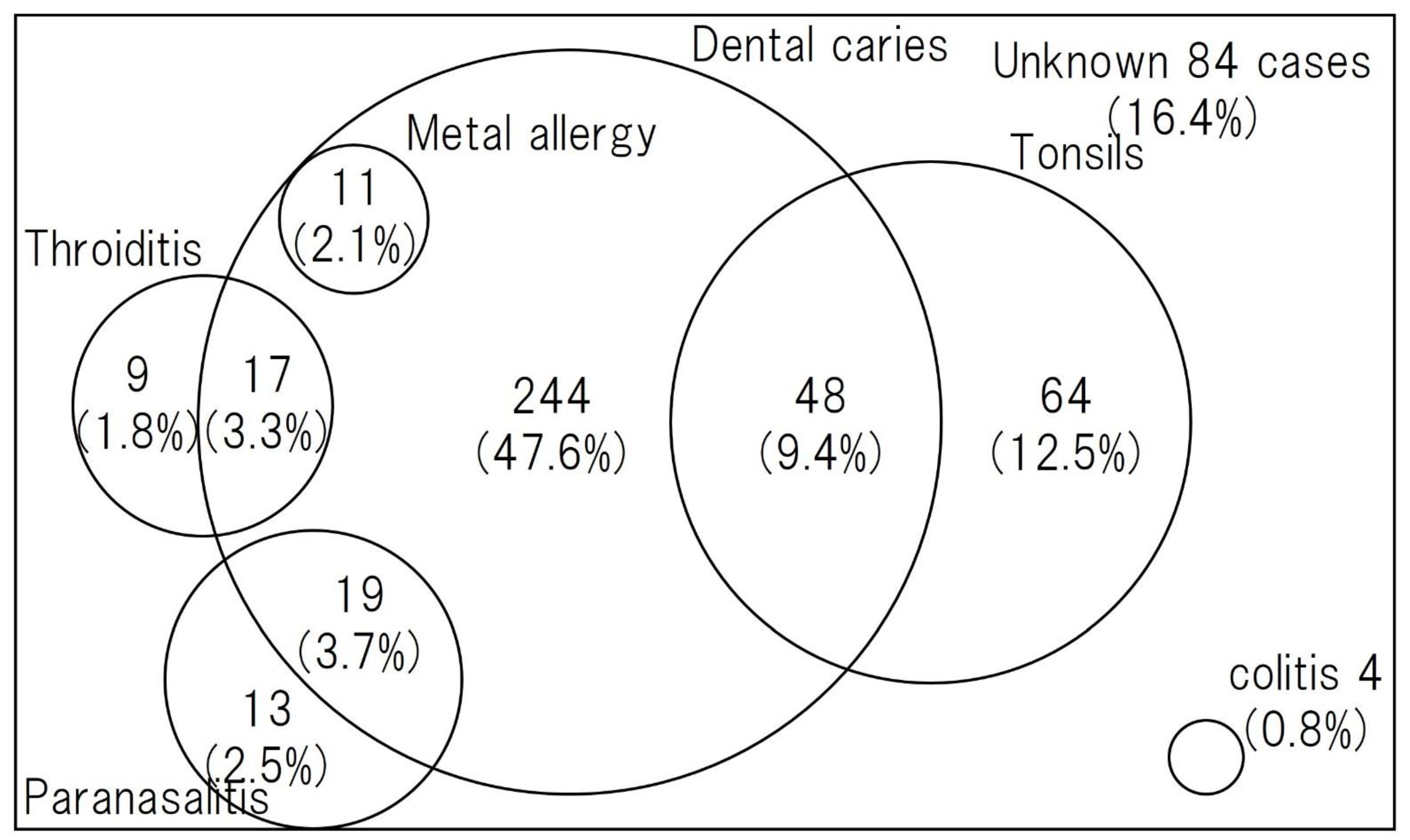

Asymptomatic chronic inflammation somewhere in the body may trigger secondary inflammation in remote organs (skin, joints, kidneys, etc.) such as PPP or glomerulonephritis. This is called “focal infection”. PPP is a typical disease that is closely associated with focal infection, and conditions that usually do not require treatment, such as asymptomatic tonsillitis (focal tonsils) [20], asymptomatic periodontitis (dental foci), chronic sinusitis, nasopharyngitis, otitis media, and cholecystitis, are thought to be involved in the development and persistence of those susceptible to PPP. Due to the high efficacy of tonsillectomy, PPP, sternoclavicular hyperplasia, and IgA nephropathy are recognized as representative diseases of tonsil foci infection. Other skin diseases such as psoriasis vulgaris and allergic purpura, osteoarticular diseases such as some chronic rheumatoid arthritis and nonspecific joint pain, SAPHO syndrome (A syndrome of unexplained bone and joint symptoms and cutaneous manifestations. “SAPHO” is an acronym for Synovitis, Acne, Pustulosis, Hyperostosis, and Osteitis.), RFAPA syndrome (Abbreviation for periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and cervical adenitis. An “autoinflammatory disease” with four main symptoms: periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and cervical lymphadenitis, which develops during infancy.), persistent low-grade fever, and Behcet’s disease have also been reported to be associated with focal infection. More than 3/4 of cases have been reported to have focal infections or other triggers for disease onset [21] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Comorbidity, including focal infection in PPP [22]. Dental caries was the most common focal infection, followed by tonsillitis and sinusitis.

3.3. PPP and Metal Allergies

Although an association with metal allergies to dental and other metals has been reported, the percentage is as low as 5% [22], and many cases do not improve with the mere removal of dental metals [26]. Even when dental treatment is performed first and dental metal removal is performed in invalid cases, the efficacy rate is not very high at 33%, suggesting that priority should be given to dental infections first [25].References

- Matsuoka, Y.; Okada, N.; Yoshikawa, K. Familial Cases of Psoriasis Vulgaris and Pustulosis Palmaris et Plantaris. J. Dermatol. 1993, 20, 308–310.

- Akiyama, M.; Takeichi, T.; McGrath, J.A.; Sugiura, K. Autoinflammatory Keratinization Diseases: An Emerging Concept Encompassing Various Inflammatory Keratinization Disorders of the Skin. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2018, 90, 105–111.

- Takahashi, T.; Fujimoto, N.; Kabuto, M.; Nakanishi, T.; Tanaka, T. Mutation Analysis of IL36RN Gene in Japanese Patients with Palmoplantar Pustulosis. J. Dermatol. 2017, 44, 80–83.

- Tobita, R.; Egusa, C.; Maeda, T.; Abe, N.; Sakai, N.; Suzuki, S.; Kawashima, H.; Hokibara, S.; Ko, J.; Okubo, Y. A Novel CARD14 Variant, Homozygous c.526G>C (p.Asp176His), in an Adolescent Japanese Patient with Palmoplantar Pustulosis. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 44, 694–696.

- Mössner, R.; Frambach, Y.; Wilsmann-Theis, D.; Löhr, S.; Jacobi, A.; Weyergraf, A.; Müller, M.; Philipp, S.; Renner, R.; Traupe, H.; et al. Palmoplantar Pustular Psoriasis Is Associated with Missense Variants in CARD14, but Not with Loss-of-Function Mutations in IL36RN in European Patients. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 135, 2538–2541.

- Twelves, S.; Mostafa, A.; Dand, N.; Burri, E.; Farkas, K.; Wilson, R.; Cooper, H.L.; Irvine, A.D.; Oon, H.H.; Kingo, K.; et al. Clinical and Genetic Differences between Pustular Psoriasis Subtypes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 143, 1021–1026.

- Mössner, R.; Wilsmann-Theis, D.; Oji, V.; Gkogkolou, P.; Löhr, S.; Schulz, P.; Körber, A.; Prinz, J.C.; Renner, R.; Schäkel, K.; et al. The Genetic Basis for Most Patients with Pustular Skin Disease Remains Elusive. Br. J. Dermatol. 2018, 178, 740–748.

- Douroudis, K.; Kingo, K.; Traks, T.; Rätsep, R.; Silm, H.; Vasar, E.; Kõks, S. ATG16L1 Gene Polymorphisms Are Associated with Palmoplantar Pustulosis. Hum. Immunol. 2011, 72, 613–615.

- Freitas, E.; Rodrigues, M.A.; Torres, T. Diagnosis, Screening and Treatment of Patients with Palmoplantar Pustulosis (PPP): A Review of Current Practices and Recommendations. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2020, 13, 561–578.

- Wang, T.S.; Chiu, H.Y.; Hong, J.B.; Chan, C.C.; Lin, S.J.; Tsai, T.F. Correlation of IL36RN Mutation with Different Clinical Features of Pustular Psoriasis in Chinese Patients. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2016, 308, 55–63.

- Hagforsen, E.; Hedstrand, H.; Nyberg, F.; Michaëlsson, G. Novel Findings of Langerhans Cells and Interleukin-17 Expression in Relation to the Acrosyringium and Pustule in Palmoplantar Pustulosis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2010, 163, 572–579.

- Murakami, M.; Ohtake, T.; Horibe, Y.; Ishida-Yamamoto, A.; Morhenn, V.B.; Gallo, R.L.; Iizuka, H. Acrosyringium Is the Main Site of the Vesicle/Pustule Formation in Palmoplantar Pustulosis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2010, 130, 2010–2016.

- Xiaoling, Y.; Chao, W.; Wenming, W.; Feng, L.; Hongzhong, J. Interleukin (IL)-8 and IL-36γ but Not IL-36Ra Are Related to Acrosyringia in Pustule Formation Associated with Palmoplantar Pustulosis. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 44, 52–57.

- Murakami, M.; Kaneko, T.; Nakatsuji, T.; Kameda, K.; Okazaki, H.; Dai, X.; Hanakawa, Y.; Tohyama, M.; Ishida-Yamamoto, A.; Sayama, K. Vesicular LL-37 Contributes to Inflammation of the Lesional Skin of Palmoplantar Pustulosis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110677.

- Misiak-Galazka, M.; Zozula, J.; Rudnicka, L. Palmoplantar Pustulosis: Recent Advances in Etiopathogenesis and Emerging Treatments. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2020, 21, 355–370.

- Harabuchi, Y.; Takahara, M. Pathogenic Role of Palatine Tonsils in Palmoplantar Pustulosis: A Review. J. Dermatol. 2019, 46, 931–939.

- Michaëlsson, G.; Gustafsson, K.; Hagforsen, E. The Psoriasis Variant Palmoplantar Pustulosis Can Be Improved after Cessation of Smoking. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2006, 54, 737–738.

- Kase, T.; Hida, T.; Yoneda, A.; Yanagisawa, K.; Yamashita, T. Analysis of 66 Cases of Pustulosis Palmaris et Plantaris Observed at Sapporo Medical University Hospital. Jpn. J. Dermatol. 2012, 122, 1375–1380.

- Fujishiro, M.; Tsuboi, R.; Ookubo, Y. A Statistical Analysis of 111 Cases of Pustulosis Palmaris et Plantaris during the Past 3 Years. Jpn. J. Dermatol. 2015, 125, 1775–1782.

- Kataura, A. Tonsillar Focal Infection-Present Clinical Situation and Prospects in the Future of Tonsillar Focal Infection. Pract. Otorhinolaryngol. 2002, 95, 763–772.

- Andrews, G.C.; Birkman, F.W.; Kelly, R.J. Recalcitrant Pustular Eruptions Of The Palms And Soles. Arch. Derm. Syphilol. 1934, 29, 548–563.

- Kobayashi, S. Treatment of Conditions That Are Difficult to Treat -Diagnosis and Treatment of Palmoplantar Pustulosis. Rinsho Derma 2018, 60, 1539–1544.

- Takahara, M.; Hirata, Y.; Nagato, T.; Kishibe, K.; Katada, A.; Hayashi, T.; Kishibe, M.; Ishida-Yamamoto, A.; Harabuchi, Y. Treatment Outcome and Prognostic Factors of Tonsillectomy for Palmoplantar Pustulosis and Pustulotic Arthro-Osteitis: A Retrospective Subjective and Objective Quantitative Analysis of 138 Patients. J. Dermatol. 2018, 45, 812–823.

- Yamamoto, Y.; Hashimoto, A.; Togashi, K.; Takatsuka, J.; Ito, A.; Shimura, H.; Ito, M. Efficacy of Treatment of Odontogenic Lesions in Palmoplantar Pustulosis. Jpn. J. Dermatol. 2001, 111, 821–826.

- Kouno, M.; Nishiyama, A.; Minabe, M.; Iguchi, N.; Ukichi, K.; Nomura, T.; Katakura, A.; Takahashi, S. Retrospective Analysis of the Clinical Response of Palmoplantar Pustulosis after Dental Infection Control and Dental Metal Removal. J. Dermatol. 2017, 44, 695–698.

- Masui, Y.; Ito, A.; Akiba, Y.; Uoshima, K.; Abe, R. Dental Metal Allergy Is Not the Main Cause of Palmoplantar Pustulosis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 33, e180–e181.

More