Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Hossam S. El-Beltagi and Version 2 by Catherine Yang.

Seaweeds have been employed as source of highly bioactive secondary metabolites that could act as key medicinal components. Seaweeds have many uses: they are consumed as fodder, and have been used in medicines, cosmetics, energy, fertilizers, and industrial agar and alginate biosynthesis. The beneficial effects of seaweed are mostly due to the presence of minerals, vitamins, phenols, polysaccharides, and sterols, as well as several other bioactive compounds. These compounds seem to have antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, antimicrobial, and anti-diabetic activities.

- antioxidant activity

- functional foods

- health benefits

- seaweeds

1. Introduction

Seaweeds have received lot of attention in recent years because of their incredible potential. Seaweeds are essential nutritional sources and traditional medicine components [1]. Marine macroalgae, sometimes known as seaweeds, are microscopic, multicellular, photosynthetic eukaryotic creatures. Based on their coloration and depending on their taxonomic classification, they can be classified into three groups: Rhodophyta (red), Phaeophyceae (brown), and Chlorophyta (green). The global variety of all algae (micro and macro) is estimated to consist of over 164,000 species with roughly 9800 of them being seaweeds, just 0.17% of which have been domesticated for commercial exploitation [2]. In recent years, seaweed has gained in popularity, making it a more versatile food item that may be used directly or indirectly in preparation of dishes or beverages [3]. Many types of seaweed are edible, they provide the body with a different variety of vitamins and critical minerals (including iodine) when consumed as food, and some are also high in protein and polysaccharides [4].

Seaweeds are now used in several industrial products as raw materials such as agar, algin, and carrageenan, but they are still widely consumed as food in several nations [5]. Seaweeds are frequently subjected to harsh environmental conditions with no visible damage; as a result, the seaweed generates a wide variety of metabolites (xanthophylls, tocopherols, and polysaccharides) to defend itself from biotic and abiotic factors such as herbivory or mechanical aggression at sea [6]. Please note that the content and diversity of seaweed metabolites are influenced by abiotic and biotic factors such as species, life stage, nutrient enrichment, reproductive status, light intensity exposure, salinity, phylogenetic diversity, herbivory intensity, and time of collection; thus, fully exploiting algal diversity and complexity necessitates knowledge of environmental impacts as well as a thorough understanding of biological and biochemical variability [7][8][7,8].

Seaweeds and their products are particularly low in calories but high in vitamins A, B, B2, and C, minerals, and chelated micro-minerals (selenium, chromium, nickel, and arsenic), as well as polyunsaturated fatty acids, bioactive metabolites, and amino acids [9]. Although current research revealed that the amount of specific secondary metabolites dictates the effective bioactive potential of seaweeds, phenolic molecules are prevalent among these secondary metabolites [10]. Furthermore, integrating seaweed into one’s daily diet has been linked to a lower risk of a range of disorders, including digestive health and chronic diseases such as diabetes, cancer, or cardiovascular disease, according to research mentioned by [11]. As a result, incorporating seaweed components into the production of novel natural drugs is one of the goals of marine pharmaceuticals, a new discipline of pharmacology that has evolved in recent decades.

2. Seaweed Resources

The word “seaweed” has no taxonomic importance; rather, it is a popular term for the common large marine algae.2.1. Brown Seaweeds

Phaeophyceae have not been well investigated, despite the fact that they have been shown to offer several health benefits. Fucoxanthin (Fuco), the principal marine carotenoid (Car), is a commercially important component of brown seaweeds, in addition to sodium alginate. Fuco contains anti-inflammatory properties. The presence of the xanthophyll pigment fucoxanthin, which is higher than chlorophyll-a, chlorophyll-c, -carotene, and other xanthophylls, gives these seaweeds their brown color [12][23]. Because of its bigger size and ease of collecting, brown seaweed is used in animal feed more often than other algae species. Brown algae are the largest seaweeds, with some species reaching up to 35–45 m in length and a wide range of shapes. Ascophyllum, Laminaria, Saccharina, Macrocystis, Nereocystis, and Sargassum are the most prevalent genera. Sargassum as a member of brown seaweeds is low in protein, but high in carbs and easily accessible minerals. They are high in beta-carotene and vitamins, and they are free of anti-nutrients [13][24].2.2. Red Seaweeds

These algae are red because of the pigments phycoerythrin and phycocyanin. The walls are made of carrageenan and cellulose agar. Both of these polysaccharides with a lengthy chain are commonly employed in the industry. Coralline algae, which secrete calcium carbonate on the surface of their cells, are an important category of red algae. Chondrus, Porphyra, Pyropia, and Palmaria are some of the most common red algae genera. The antioxidant activity of Phaeophyta (brown seaweeds) is higher than that of green and red algae [14][25].2.3. Green Seaweeds

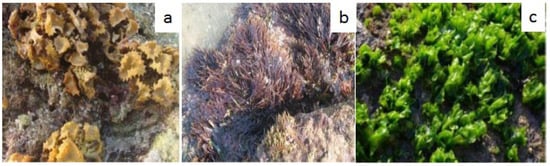

The majority of the species are aquatic, living in both freshwater and marine habitats. The green color of these algae is due to chlorophyll-a or chlorophyll-b. Some of them are terrestrial, meaning they grow in soil, trees, or rocks. Ulva is one of the most common green seaweeds. Ulva, Cladophora, Enteromorpha, and Chaetomorpha are the most common genera. Green algae thrive in regions with lots of light, including shallow waterways and tide pools. Ulva sp. has a high protein content (typically > 15%) and a low energy content and is abundant in both soluble and insoluble dietary fiber (glucans) [15][26]. The main types of seaweeds are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Three example species of brown (

a

) red (

b

) and green (

3. Bioactive Compounds

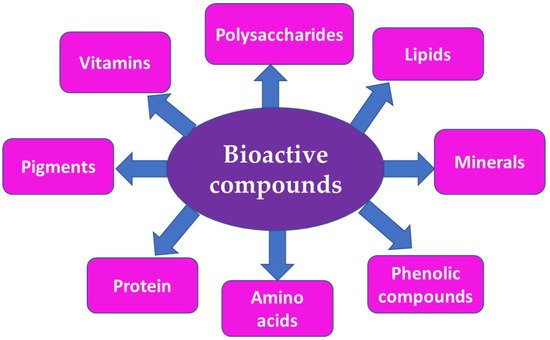

The chemical composition of algae varies depending on the species, cultivation location, meteorological conditions, and harvesting period. Because of the broad diversity of compounds produced by seaweeds, they are currently considered to be prospective organisms for contributing new physiologically active chemicals for the production of novel food (nutraceutical), cosmetic (cosmeceutical), and medical compounds. Polyphenolic compounds, carotenoids, minerals, vitamins, phlorotannins, peptides, tocotrienols, proteins, tocopherols, and carbohydrates (polysaccharides) are considered to be a great variety of bioactive compounds (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Main bioactive compounds from marine seaweeds.

3. Biological Activities

3.1. Antioxidant Activity

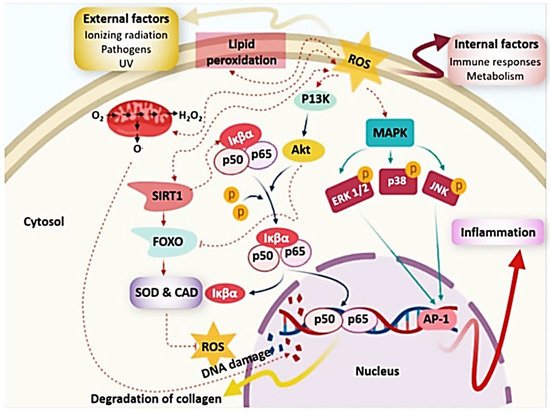

An imbalance in the creation and neutralization of free radicals causes oxidative stress, which leads to a variety of degenerative illnesses [17][229]. Several free radicals, particularly reactive oxygen species (ROS), were created in living organisms as a result of metabolic activity, and hence have an impact on health (Figure 37). ROS were formed in form of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), superoxide radical (O2−), hydroxyl radical (·OH), or nitric oxide (NO). Oxidative stress causes unconscious or prominent enzyme activation, as well as oxidative damage for cellular systems [18][230]. ROS attack or damage important macromolecules including lipids membrane, proteins, or DNA, resulting in a variety of conditions include inflammatory or neurodegenerative diseases, diabetes mellitus, cancer, or severe tissue injuries [19][20][231,232] (Figure 37).

Figure 37. Damage caused via reactive oxygen species (ROS). Adapted from ref. [21] obtained from mdpi journals.

Damage caused via reactive oxygen species (ROS). Adapted from ref. [233] obtained from mdpi journals.

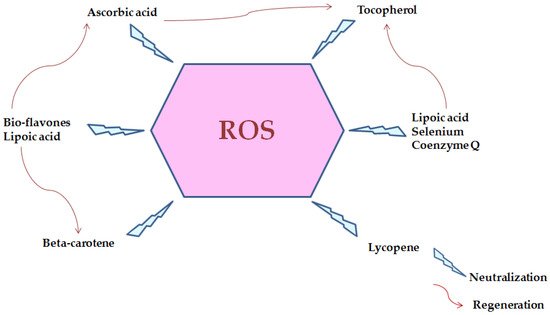

Figure 48.

Reactive oxygen species and neutralization by several biomolecules.

3.2. Antimicrobial Activity

Susceptibility testing of harmful microorganisms (e.g., bacteria and fungi) in the presence of possible compounds of interest is the focus of antimicrobial activity assays. Microbial infections can cause life-threatening illnesses, resulting in millions of deaths each year. Despite the fact that the discovery of penicillin pushed many aggressive pathogenic bacteria back, many strains evolved and developed remarkable resistance mechanisms to most antibiotics [26][238]. Variable solvents have different antibacterial action depending on their solubility and polarity. As a result, chemical compounds isolated from various seaweeds should be optimized for antibacterial activity by selecting the optimal solvent system [27][239]. Micro-algal cell-free extracts are already being studied as food and feed additives in an attempt to replace synthetic antibacterial chemicals currently in use. According to Tuney et al. [28][240], the antibacterial action of the extract is attributable to various chemical agents found in the extract, such as flavonoids, triterpenoids, and other phenolic compounds or free hydroxyl groups. Extraction procedures, solvents used, and the time window in which samples were collected all have the potential to alter antibacterial activity [29][241]. A variety of organic solvents had previously been recommended for screening algae for antibacterial activity.3.3. Anticancer Activity

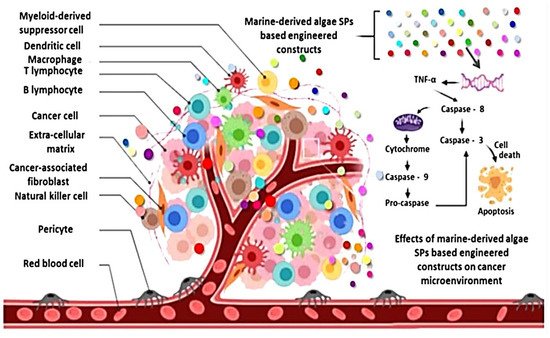

Cancers are life-threatening diseases that are considered to be a major public health issue around the world [30][31][246,247]. Uncontrolled cell development spreads into the surrounding tissues, resulting in the formation of a tumor mass [32][248]. Much research has looked into the anticancer potential of natural compounds derived from seaweeds, as well as the signaling pathways involved in anticancer activity [33][249]. Because those secondary metabolites have no hazardous effects, they have seen a lot of progress in the treatment of numerous diseases, including cancer. Thymoquinone (TQ) is one of the most important bioactive elements of black seeds, and it has been found to have numerous health advantages, including cancer prevention and treatment. Following on this, Algotiml et al. [34][250] studied the effect of biosynthesized Red Sea marine algal silver nanoparticles AgNPs on anticancer and antibacterial properties and the authors stated that due to their relatively moderate side effects, marine resources are currently being increasingly examined for antibacterial and anticancer medication prospects. In addition, kappa-carrageenan extracted from Hypnea musciformis (Hm-SP) decreased proliferation of MCF-7 or SH-SY5Y cancer cell lines [35][255]. Additionally, polysaccharides derived from Sargassum fusiforme (SFPS) reduced SPC-A-1 cell proliferation in vitro and tumor formation in vivo [36][256]. Additionally, Ji and Ji [37][257] found that commercial laminaran (400–1600 g/mL) inhibited the growth of human colon cancer LoVo cells through stimulating mitochondrial or DR pathways. Additionally, Fucoidans isolated from Undaria pinnatifida have anticancer potential comparable to commercial fucoidans in cell lines Hela (human cervical), PC-3 (human prostate), HepG2 (human hepatocellular liver carcinoma), or A549 (carcinomic human alveolar basal epithelial) [38][258]. Moreover, previous study reported that fucoidan isolated from Sargassum hemiphyllum may increase miR-29b expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells, which aids in the lowering of DNA methyltransferase 3B expression [39][259]. Moreover, Fucoidans from Fucus vesiculosus were revealed to have anticancer potential, inducing apoptosis in MC3 human mucoepidermoid carcinoma cells via caspase-dependent apoptosis signaling cascade [40][260] (Figure 59).

3.4. Antidiabetics Activity

As a result of an unhealthy lifestyle, obesity, and stress, diabetes is becoming a global illness. Additionally, obesity has been on the rise in Saudi Arabia as a result of changing lifestyles and socioeconomic status [40][41][260,261]. There is a close association between obesity and type 2 diabetes. Drugs that suppress the enzymes α-glucosidase and α-amylase, which break down starch into glucose before it is absorbed into the bloodstream, could be used to treat diabetes [42][262]. It is necessary to look for effective therapeutic natural medications with less side effects. Garcimartn et al. [43][263] showed that a α-glucosidase inhibitory effect on restructured pork treated with seaweeds such as Undaria pinnatifida, Himanthalia elongata, and Porphyra umbilicalis caused a reduction in the blood glucose absorption. Padina tetrastromatica phenolic extracts inhibited both α-glucosidase and α-amylase, with higher inhibition linked with a higher phenolic concentration in the extracts. The extracts inhibited α-glucosidase (IC50 value of 28.8 g mL−1) and -amylase (IC50 value of 47.2 g mL−1) by 38.9 and 26.8%, respectively [44][264]. Similarly, α-glucosidase inhibitory action was observed in methanol, ethanol, and acetone extracts of Durvillea antarctica, methanol extracts of Ulva sp., and acetone extracts of Lessonia spicata [45][265]. Methanol extracts of Padina tenuis (400 µg mL−1) and ethanol extract of Eucheuma denticulatum (10 mg mL−1) and Sargassum polycystum (10 mg mL−1) significantly inhibited α-amylase by 60%, 67%, and 46%, respectively [46][266]. Recently, the acetone extract (80%) of brown seaweed Turbinaria decurrens was studied for its antihyperglycemic effects in alloxan induced diabetic wistar male rats [47][267]. The results showed a significant reduction in postprandial blood glucose levels of seaweed extracts treated rats to 180.33 mg dL−1 and 225.33 mg dL−1 at the dose of 300 mg/kg body weight and 150 mg/kg body weight, respectively, compared to diabetic control (565.0 mg dL−1) and positive control (115.33 mg dL−1).4. Seaweeds in Bio-Manufacturing Applications

Modern consumers are well aware of the nutritional value of food and the negative impact that synthetic preservatives may have worse effect on their health, so it is unsurprising that they prefer fresh and lightly preserved foods that are free of chemical preservatives, but contain natural compounds that may benefit their health [48][306].4.1. Fertilizer and Soil Conditioners

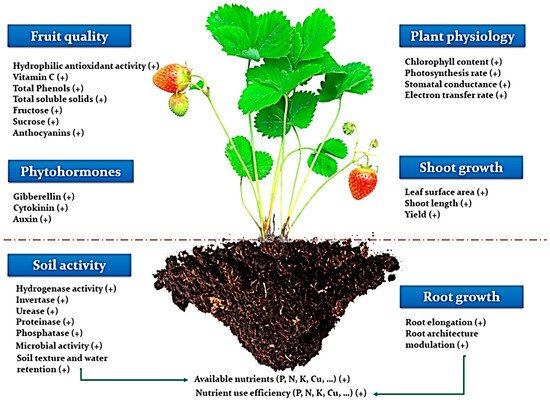

Seaweed extracts have been frequently employed in agriculture in recent years to increase crop yield. This improvement is achieved by stimulating various physiological processes involved in plant growth and development, as well as improving final product quality (Figure 610). The use of traditional chemical fertilizers has expanded dramatically as result of world’s fast-growing population or ever-increasing food demand [49][307]. The usage of these chemical fertilizers, as well as their impacts, notably on environment, has become major source of worry [50][308]. As a result, farmers began to switch to organic farming rather than using synthetic agricultural fertilizers. Seaweeds are abundant or long-lasting resources discovered along the world’s coastlines, and they are important sources of food, feed, biofuels, cosmetics, fertilizers, nutraceuticals, and pharmaceuticals [51][52][309,310]. Due to their commercial importance or potential applications, seaweeds are used as fodder, cosmetics, human food, or biofertilizers [53][311]. Because of availability of various trace elements, vitamins, growth regulators, or amino acids, macroalgae extracts are currently being used as foliar sprays or presoaking for boosting growth or production of variety of plants, particularly crops [54][312]. Each year, more than 15 million tons of seaweed is produced, with much of it used as biofertilizers in agriculture or horticulture industries [55][56][313,314].

Figure 610. Illustration demonstrating beneficial effects of seaweed extracts on the entire soil-plant system. Such impacts include increased fruit quality and phytohormone content in plants, increased soil enzymatic activity, improved roots system, and overall physiological properties of plants. Adapted from ref. [57][315] obtained from mdpi journals.

4.2. Medical and Pharmaceutical Use

5.2.1. Biomedical Applications of Seaweeds

Bioactive chemicals found in seaweeds have features that make them appealing for biomedical applications. Many species of seaweeds have been employed in traditional medicine for a long time, notably in Asian nations, against goiter, nephritic disorders, anthelmintic, catarrh, and a few other ailments as medicaments or pharmaceutical auxiliaries, long before scientific study information [58][316]. Fucus vesiculosus has been used as a medicinal drug, primarily due to its iodine content, for obesity defects and goiters [58][316], for the treatment of sore knees [59][317], healing wounds [60][318], and also as herbal teas for their laxative effects [61][319]. Chondrus crispus (Rhodophyta) carrageens have been used as mucilage against diarrhea, dysentery, gastric ulcers, and as a component of several health teas, such as for colds, for a long time. Gelidium cartilagineum (Rhodophyta) has been used in pediatric medicine in Japan for colds and scrofula [62][284]. Ulva lactuca (Chlorophyta) has been used for gout and as an astringent in folk medicine [62][284]. Rhodophyta extracts are very promising natural chemicals that could be used in biomedicine. Many species of Asian seaweeds are employed in traditional medicine, including Gracilaria spp. (Rhodophyta), which is used as a laxative, Sargassum spp. (Phaeophyceae), which is used to treat Chinese influence, and Caloglossa spp., Codium spp., Dermonema spp., and Hypnea spp. (Rhodophyta) [63][327]. Carrageenans’ biological actions make them attractive candidates for future antitumoral therapeutics since they activate antitumor immunity [64][328]. Kappaphycus species (Rhodophyta), for example, are used to treat ulcers, headaches, and tumors [63][327]. Antitumoral efficacy of carrageenans derived from Kappaphycus striatum against human nasopharyngeal carcinoma, human gastric carcinoma, and cervical cancer cell lines [65][329]. The bioactivity of chemicals from various Laurencia species (Rhodophyta) was investigated. In vitro, certain halogenated metabolites of Laurencia papillosa showed action against Jurkat (acute lymphoblastic leukemia) human tumor cells [66][330]. Laurencia obtuse extracts, specifically three sesquiterpenes, have been extracted and tested against Ehrlich ascites cancer cells. The sesquiterpenes were found to have antitumoral action against Ehrlich ascites cells [67][331]. Gracilaria edulis ethanol extracts showed antitumor efficacy in mice with ascites tumors [68][332]. Undaria pinnatifida (Phaeophyceae) has anti-inflammatory qualities and can be used to treat postpartum depression in women. This alga can also be used to treat edema and as a diuretic. Celikler et al. [69][333] investigated the antigenotoxic effect of Ulva rigida extracts in human cells in vitro (Chlorophyta). Seaweeds have been suggested as a way to avoid neurogen-erative illnesses in investigations over the last decade [70][334]. Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), Huntington’s disease (HD), and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) are the most frequent [70][334]. According to Bauer et al., several studies highlighted the use of algal polysaccharides for the treatment of neurodegenerative illnesses [71][335]. Park et al. [72][336] found that mice treated with fucoidan extracts from Ecklonia cava had better memory and learning; consequently, the study implies favorable results in future human trials. In comparison to the control group, mice treated with polysaccharide isolated from Sargassum fusiforme demonstrated enhanced memory and cognition [73][337]. Dieckol and phlorofucofuroeckol, two phlorotannins from Ecklonia cava, are linked to an increase in the main central neurotransmitters in the brain, particularly Acetylcholine (ACh) [74][338]. Ahn et al. [75][339] investigated Eisenia bicyclis phlorotannins and found that 7-phloroeckol and phlorofucofuroeckol A were powerful neuroprotective agents against induced cytotoxicity, while eckol had a weaker impact.4.2.2. Pharmaceutical Applications of Seaweeds

Bioactive chemicals from seaweeds are used in the pharmaceutical industry to help develop new formulations for revolutionary treatments and to replace synthetic components with natural ones. Bioactive chemicals found in seaweeds have important pharmacological properties, including anticoagulant, antioxidant, antiproliferative, antititumoral, anti-inflammatory, and antiviral effects [76][340].Table 11.

The potential pharmacological activity of brown, red and green seaweeds.

| Component | Properties/Activities | Seaweed | Doses | Models | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fucoxanthins | Antitumoral activity on lung cancer cells |

Laminaria japonica | 12.5–100 μM | Female and male (1:1 ratio) BALB/c nude mice (18–20 g; 6–8 weeks of age) | [77][341] |

| Antitumoral activity on MCF-7, HepG-2, HCT-116 cells | Colpomenia sinuosa, Sargassum prismaticum | 100 and 200 mg/kg | Paracetamol-administered rats (one dose of 1 g/kg) | [78][342] | |

| Antitumoral activity on SiHa, Malme-3M cells | Undaria pinnatifida | 1.5625, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 80, 100 µM | Human cell lines | [79][343] | |

| Antimicrobial activity | Cladosiphon okamuranus | 2–2000 µg/mL. | Helicobacter pylori | [80][344] | |

| Antimicrobial activity | Laminaria japonica | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 7.5 mg/mL | Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli | [81][345] | |

| Antimicrobial activity | Fucus vesiculosus | 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 mg/mL | Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus licheniformis, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus epidermidis |

[82][346] | |

| Antiviral activity against ECHO-1, HIV-1, HSV-1, HSV-2 | Fucus evanescens | 200 μg/mL | Female outbred mice (16–20 g) | [83][347] | |

| Sulfate polysaccharide | Antiviral activity against HSV-1, HVS-2 |

Sargassum patens | 0.78–12.5 μg/mL | Vero cells (African green monkey kidney cell line) | [84][348] |

| Anti-obesity, antidiabetic activities | Gracilaria lemaneiformis | 5–10% Seaweed powder | Dawley laboratory rats (4 to 5 months old, 250–300 g) | [85][349] | |

| Phloroglucinol | Anti-inflammatory activity | Ecklonia cava | 1, 5, 10, 50 100 µM |

HT1080 and RAW264.7 cells |

[86][350] |