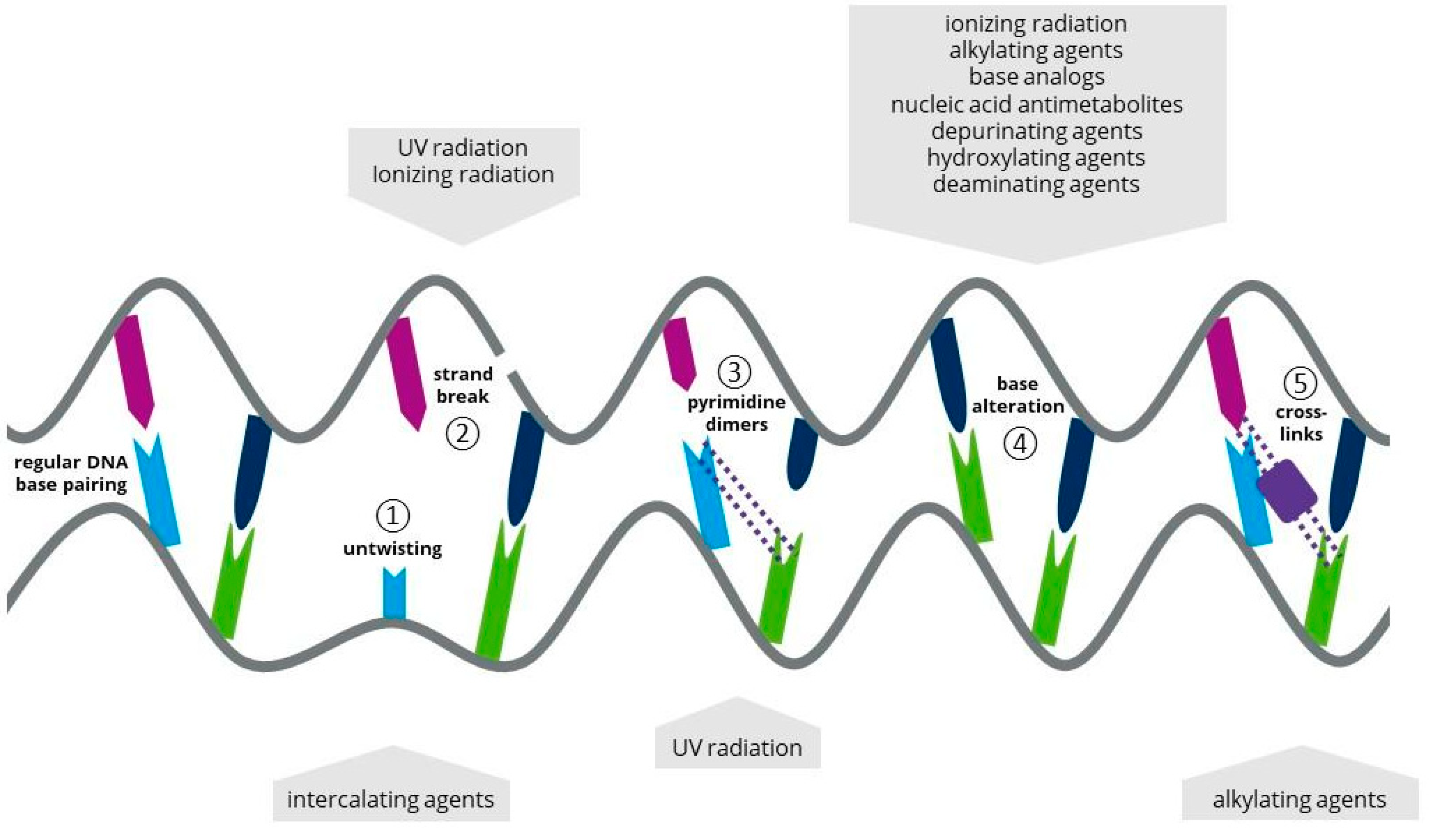

Microalgal biomass and metabolites can be used as a renewable source of nutrition, pharmaceuticals and energy to maintain or improve the quality of human life. Microalgae’s high volumetric productivity and low impact on the environment make them a promising raw material in terms of both ecology and economics. To optimize biotechnological processes with microalgae, improving the productivity and robustness of the cell factories is a major step towards economically viable bioprocesses. The success of a random mutagenesis approach using microalgae is determined by multiple factors involving the treatment of the cells before, during and after the mutagenesis procedure. Using photosynthetic microalgae, the supply of light quality and quantity, as well as the supply of carbon and nitrogen, are the most important factors. Besides the environmental conditions, the type of mutagen, its concentration and exposure time are among the main factors affecting the mutation result.

- random mutagenesis

- algae

- mutagens

- strain development

- microalgal biotechnology

1. Physical Mutagens in Microalgal Biotechnology

1.1. Ultraviolet Light

1.2. Ionizing Radiation

1.3. Atmospheric and Room Temperature Plasma

1.4. Laser Radiation

| Mutagen | Method, Exposure Time, Source, Distance, Recovery Time | Reference Microalgae | Mutation Results | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutated trait |

WT * | M ** | ||||

| UV | UV 18 W, for 13 min, 15 cm, 24 h darkness | Chlorella vulgaris Y-019 |

neutral lipid accumulation [g/g dry wt] |

0.11 | 0.26 | [24][36] |

| UV-C | UV-C 253.7 nm, 30-W, 3–30 min, 9 cm, 24 h darkness | Chlorella sp. | protein content [g/L] | 0.0242 | 0.0688 | [25][37] |

| UV-C 254 nm 1.4 mW/cm2 for 60 s, 15 cm, 16 h darkness | Chlorella vulgaris | fatty acids 16:0;18:0, 20:0 [% of total fatty acids] | 27.9; 3.9; 11.9 | 47.4; 5.9; 19.9 | [26][68] | |

| UV-C 254 nm, 15 W, (Vilber–Lourmat, France), for 30–180 s, 5 cm, 24 h darkness | natural isolates of photosynthetic microorganism | lipid content though Nile red autofluorescence; with fluorescence emission | 35; 1081 | 983; 89,770 | [27][38] | |

| UV-C 40,000 μJ/cm, 254 nm, overnight darkness | Scenedesmus obliquus | trans-fatty acid productivity [g/(L·d)] |

0.095 | 0.112 | [28][69] | |

| UV-C 254 nm 340 mW cm2, for 3–32 min, 13.5 cm, 24 h darkness |

Isochrysis affinis galbana | total fatty acid [g/g dry wt] |

0.262 | 0.409 | [29][40] | |

| UV-C, for 1–10 min, 40 cm, overnight darkness | Chlorella vulgaris | lipid content [g/g] | 0.58 | 0.75 | [30][35] | |

| Gamma irradiation | 10 doses of irradiation 50–7000 kGy, 60Co gamma ray irradiator, room temperature |

Scenedesmus sp. | lipid productivity [g/L·d] |

0.0648 | 0.097 | [31][70] |

| ARTP | He RF power 100 W, plasma temperature 25–35 °C, for 20; 40; 60 and 80 s, 2 mm | Spirulina platensis | Carbohydrates productivity [g/L·d] |

0.0157 | 0.026 | [15][59] |

| He RF power 100 W, plasma temperature 25–35 °C, 20–60 s, 2 mm | Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | H2 production [mL/L] | ~16.1 | 84.1 | [32][71] | |

| He RF power 150 W, for 100 s | Crypthecodinium cohnii | biomass concentration [g dry wt/L] |

3.60 | 4.24 | [33][72] | |

| Heavy ion beam | 12 C6+ ion beam 31 keVµm−1 160 Gy, | Nannochloropsis oceanica | lipid productivity [g/L·d] | 0.211 | 0.295 | [34][73] |

| 12 C6+ ion beam, 90 Gy | Desmodesmus sp. | lipid productivity [g/L·d] | 0.247 | 0.298 | [35][74] | |

| Low-energy ion beam implementation | N+ ion beam chamber pressure 10−2 Pa Dose of implantation 0.3–3.3·1015 ions cm−2 s−1 |

Chlorella pyrenoidosa | lipid productivity [g/ L·d]; Lipid content [g/g dry wt] | 47.7; 0.337 | 64.4; 0.446 | [36][75] |

| laser radiation | He–Ne laser 808 nm, 6 W, 4 min, 24 h darkness | C. pyrenoidesa | lipid content [g/g dry wt] | 0.354 | 0.780 | [22][66] |

| Nd:YAG laser 1064 nm, 40 mW 8 min, 24 h darkness | Chlorella vulgaris | lipid content [g/g dry wt] | 0.315 | 0.525 | [22][66] | |

| Nd:YAG laser 1064 nm, 40 mW 2 min, 24 h darkness | Chlorella pacifica | lipid content [g /L−1]] |

0.033 | 0.088 | [37][76] | |

| semiconductor laser 632 nm, 40 mW, 4 min, 24 h darkness |

Chlorella pacifica | lipid content [g /L−1]] |

0.033 | 0.077 | [37][76] | |

2. Chemical Mutagens in Microalgal Biotechnology

2.1. Alkylating Agents as a Chemical Mutagen

2.2. Base Analogs (BAs) as a Chemical Mutagen

2.3. Antimetabolites (AMs) as a Chemical Mutagen

2.4. Intercalating Agents (IAs) as a Chemical Mutagen

2.5. Other Approaches for Chemical Mutagenesis

Chemical mutagens applied on microalgae.

| Mutagen | Mutagen Concentration, Time of Exposure | Method, Exposure Time, Source, Distance, Recovery Time | Reference Microalgae | Mutation Results | References | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutated trait |

WT * | M ** | |||||||||||

| EMS | EMS 0.1–1.2 Mfor 60 min | Nannochloropsis sp. | Mutated trait | fatty acid methyl esters g/g of dry wt] | WT * | 0.123 | M ** | 0.238 | [101] | ||||

| EMS | EMS 0.4–1 g/Lfor 60–120 min | EMS 0.1–1.2 M for 60 min | Haematococcus pluvialis | Nannochloropsis sp. | total carotenoid; Astaxanthin[g/g of dry wt] | fatty acid methyl esters [g/g of dry wt] | 0.02; 0.005 | 0.123 | 0.02;0.019 | 0.238 | [102] | [65] | |

| EMS 0.4–1 g/L for 60–120 min | EMS 300 mM for 60 min | Haematococcus pluvialis | Chlorella vulgaris | total carotenoid; Astaxanthin [g/g of dry wt] | protein content [g/g of dry wt] | 0.02; 0.005 | 0.353 | 0.02; 0.019 | 0.455 | [66] | [34] | ||

| EMS 300 mM for 60 min | EMS 0.2–0.4 M for 2 h in darkness | Chlorella vulgaris | protein content [g/g of dry wt] | violaxanthin [mg/L culture] | 0.353 | 1.64 | 0.455 | 5.23 | [67] | [103] | |||

| EMS 0.2–0.4 M for 2 h in darkness | EMS 0.1–0.2 M | Chlorella vulgaris | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | violaxanthin [mg/L culture] | total carotenoids [g/g dry wt] | 1.64 | 0.009 | 5.23 | 0.011 | [68] | [104] | ||

| EMS 0.1–0.2 M | EMS 0.2 M for2 h in the dark | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | Dunaliella tertiolecta | total carotenoids [g/g dry wt] | Zeaxanthin [μg/106·cells] | 0.009 | 0.131 | 0.011 | 0.359 | [69] | [105] | ||

| EMS 0.2 M for 2 h in the dark | EMS 20–40 µL/mL for 2 h | Dunaliella tertiolecta | Chlamydomonasreinhardtii | Zeaxanthin [μg/106·cells] | fatty acid methyl esters yield [%] | 0.131 | 6.53 | 0.359 | 7.56 | [70] | [106] | ||

| EMS 20–40 µL/mL for 2 h | EMS 0.2 M for2 h in the dark | Chlamydomonas | Dunaliellasalina | reinhardtii | fatty acid methyl esters yield [%] | carotenoid synthesis [Mol Car/Mol Chl] | 6.53 | 0.99 | 7.56 | 1.24 | [71] | [107] | |

| EMS 0.2 M for 2 h in the dark | EMS 100 μ mol mL−1, for 30 min | Dunaliella | Chlorella | salina | sp. | carotenoid synthesis [Mol Car/Mol Chl] | lipid content (g/g of dry wt]; productivity [g/(L·d)] | 0.99 | 0.247; 0.1536 | 1.24 | 0.356; 0.2487 | [72] | [108] |

| EMS 100 μ mol mL−1, for 30 min | Chlorella sp. | EMS 0.4M, for 60 min | lipid content [g/g of dry wt]; productivity [g/(L·d)] | Coelastrum sp. | 0.247; 0.1536 | Astaxanthin content [g/L] | 0.356; 0.2487 | 0.0145 | [73] | 0.0283 | [109] | ||

| EMS 0.4 M, for 60 min | EMS + UV | Coelastrum sp. | UV + EMS 25 mM for 60 min | Astaxanthin content [g/L] | Chlorella vulgaris | 0.0145 | lipid content [%] | 0.0283 | 100 | [74] | 167 | [85] | |

| EMS + UV | UV 5–240 s, 245 nm + EMS 0.24 mol/L for 30 min | UV + EMS 25 mM for 60 min | Nannochloropsis salina | Chlorella vulgaris | fatty acid methyl ester [g/g of dry wt] | lipid content [%] | 0.175 | 100 | 0.787 | 167 | [110] | [46] | |

| UV 5–240 s, 245 nm + EMS 0.24 mol/L for 30 min | MNNG | Nannochloropsis salina | MNNG 0.1 mM for 60 min | fatty acid methyl ester [g/g of dry wt] | Haematococcus pluvialis | 0.175 | Total carotenoid content [g/L] | 0.787 | ~0.067 | [75] | 0.089 | [80] | |

| MNNG | MNNG 5 µg/mL for 60 min | MNNG 0.1 mM for 60 min | Chlorella sp. | Haematococcus pluvialis | max. growth rate under alkaline conditions [ d−1] | Total carotenoid content [g/L] | 0.064 | ~0.067 | 0.554 | 0.089 | [111] | [41] | |

| MNNG 5 µg/mL for 60 min | MNNG 0.02 mol/Lfor 60 min | Chlorella sp. | Nannochloropsisoceanica | max. growth rate under alkaline conditions [ d−1] | Total lipidcontent [g/g]Lipid productivity [g/(L·d)] | 0.064 | 0.241; 0.0065 | 0.554 | 0.299; 0.0086 | [76] | [33] | ||

| MNNG 0.02 mol/L for 60 min | MNNG 0.1–0.2 M | Nannochloropsis | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | oceanica | Total lipid content [g/g] Lipid productivity [g/(L·d)] | total carotenoids [g/g dry wt] | 0.241; 0.0065 | 0.009 | 0.299; 0.0086 | 0.011 | [50] | [104] | |

| MNNG 0.1–0.2 M | MNNG 0.2 mg/mL | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | Chlorella sorokiniana | total carotenoids [g/g dry wt] | Lutein content [g/L] | 0.009 | 0.025 | 0.011 | 0.042 | [69] | [83] | ||

| MNNG 0.2 mg/mL | Chlorella sorokiniana | MNNG 0.25–0.5 mM | Lutein content [g/L] | Botryosphaerella sp. | 0.025 | lipid[g dry wt/(m2 day)]; biomass productivity [g dry wt/(m2·day)] | 0.042 | 1.0; 3.2 | [44] | 1.9; 5.4 | [84] | ||

| MNNG 0.25–0.5 mM | NMU | Botryosphaerella sp. | NMU 5 mM for60–90 min | lipid [g dry wt/(m2 day)]; biomass productivity [g dry wt/(m2·day)] | Nannochloropsis oculata | 1.0; 3.2 | Total fatty acid [g/g dry wt] | 1.9; 5.4 | 0.0634 | [45] | 0.0762 | [82] | |

| NMU | DES + UV | NMU 5 mM for 60–90 min | UV 7–11 min 254 nm +DES 0.1–1.5% (V/V) 40 min | Nannochloropsis oculata | Haematococcus pluvialis | Total fatty acid [g/g dry wt] | astaxanthin content [mg/L] | 0.0634 | ~0.031 | 0.0762 | ~0.089 | [43] | [81] |

| DES + UV | 5BU | UV 7–11 min 254 nm + DES 0.1–1.5% (V/V) 40 min | 5BU 1 mM for 48 h | Haematococcus pluvialis | Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | astaxanthin content [mg/L] | O2 tolerance [%] | ~0.031 | 100 | ~0.089 | 1400 | [42] | [112] |

| 5BU | 5′FDU | 5BU 1 mM for 48 h | 5′FDU 0.25 and 0.50 mM for 1 week | Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | Chlorella vulgaris | O2 tolerance [%] | fatty acids 16:0; 18:0; 20:0 [% of total fatty acids] | 100 | 27.9; 3.9; 11.9 | 1400 | 46.9; 5.5; 18.5 | [77] | [68] |

| 5′FDU | Acriflavin | 5′FDU 0.25 and 0.50 mM for 1 week | Acriflavin 2–8 μg/mL for 1–3 d in darkness | Chlorella vulgaris | Chlamydomonas reinhardtii zyklo | fatty acids 16:0; 18:0; 20:0 [% of total fatty acids] | Loss of respiratory rate [nmol O2/(min·107 cells)] through loss of mitochondrial DNA | 27.9; 3.9; 11.9 | 23.2 | 46.9; 5.5; 18.5 | 3.7 | [26] | [100] |

| Acriflavin | Acriflavin 2–8 μg/mL for 1–3 d in darkness | Chlamydomonas reinhardtii zyklo | Loss of respiratory rate [nmol O2/(min·107 cells)] through loss of mitochondrial DNA | 23.2 | 3.7 | [64] | |||||||

3. Further Approaches in Random Mutagenesis

Recently, combined mutagenesis approaches have generated high interest as results indicated that they have a higher success rate than individual approaches. For instance, Wang et al. [42][81] applied a two-step random mutagenesis protocol to Haematococcus pluvialis cells using first UV irradiation, then EMS and DES mutagenesis, causing astaxanthin production to increase by a factor of 1.7 compared to the wild strain. Beacham et al. [75][110] used a reverse protocol for Nannochloropsis salina, starting with exposure to EMS, followed by UV irradiation, yielding a three-fold increase in cellular lipid accumulation. Comparable results were achieved by Sivaramakrishnan and Incharoensakdi [78][113], who exposed Scenedesmus sp. to UV irradiation in combination with oxidative stress by H2O2.

Other approaches can be used to select desired microalgal cells if the results obtained by random mutagenesis are insufficient. Among them, Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) is commonly used to adapt the physiology of cells to specific process conditions, such as high temperatures [79][114]. Its principle is based on natural selection, as presented in the Darwinian Theory, on the laboratory bench [80][115], and includes extensive cultivation in a specifically designed lab environment so that enhanced phenotypes can be selected after a long period of time [81][116]. The environmental conditions that can be altered include light irradiation, lack of nutrients, such as nitrogen, osmotic, temperature and oxidative stress [80][82][83][115,117,118]. Connecting the results of ALE with whole genome sequencing and “omics” methods enables gene functions to be discovered easily [81][116]. However, ALE does not prevent gene instability that might occur more often than in randomly mutated cells [79][82][114,117].

Additional environmental factors can be applied on microalgae; for example, Miazek et al. [84][119] reviewed the use of metals, metalloids and metallic nanoparticles to enhance cell characteristics. Moreover, phytohormones or chemicals acting as metabolic precursors have already been applied to microalgae [85][120]. A discussion of the methods used in the latter case exceeds the scope of this resviearchw.

More recently, a new technique was developed, known as Space Mutation Breeding (SMB). This technique may have direct or indirect effects on the growth and metabolic activities of microalgae, due to the unusual environment of space, characterized by high-energy ionic radiation, space’s magnetic field, ultra-high vacuum and microgravity [86][121]. The SMB technique provides some advantages, such as the great improvement in species’' qualities in a short time [87][122]. This was achieved by Chen Zishuo et al. [86][121], with a seawater Arthrospira platensis mutant, yielding a sugar content 62.26% higher than the wild type.

Reference