Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Aspasia Pachiou and Version 2 by Lindsay Dong.

Dental eruption refers to the vertical displacement of a tooth from its initial non-functional towards its functional position. Tooth eruption disorders may be expressed in various clinical conditions, which may be grouped as “primary retention” and “secondary retention”. Tooth eruption disorders can be manifested in several clinical conditions where the oral location, the number of the affected teeth, and the etiology of the disorders vary considerably. Eruption failure is often attributed to genetic factors.

- primary failure of eruption

- PFE

- ankylosis

- tooth eruption disorders

1. Introduction

Dental eruption constitutes the physiologic process where a tooth is vertically displaced from its initial non-functional, developmental position towards its functional position, emerging through the bone of the alveolar process and the mouth epithelium, in order to occlude with its antagonist. This process is triggered by the formation of the periodontal ligament [1].

The physiological eruption procedure of one or more teeth is likely to be disrupted by local or genetic factors. Due to the slow rate of the tooth eruption and the fact that access to this ongoing process is deemed challenging, the exact procedure remains unclear [1]. A variety of syndromes involving eruption failure have been mentioned, among which cleidocranial dysplasia, Gardner syndrome, osteoglophonic dwarfism, regional odontodysplasia, oculodental syndrome, Rutherfurd type, Nance–Horan syndrome, Cherubism, Albers-Schönberg osteopetrosis, McCune–Albright syndrome, hypodontia–dysplasia of nails syndrome, osteopetrosis, mucopolysaccharidosis, and GAPO syndrome [2]. In cleidocranial dysplasia patients, a combination of delayed tooth eruption and a high bone width of the upper and the lower arches was observed. In these patients, the paracrine signal for bone remodeling could account for the incomplete tooth eruption [3].

2. Eruption Failure

A non-normal tooth eruption path may occur from the presence of a given mechanical obstacle (with idiopathic or pathological origin) or as a result of the disruption of the tooth eruption mechanism itself [4]. The tooth eruption process involves a synchronized procedure where consecutive signaling events take place between the tooth pocket and the osteoblast and osteoclast cells of the alveolar process [5]. A disorder caused or not by a syndrome (of genetic or otherwise origin) might lead to the disruption of the aforementioned process, manifested either as a delayed eruption [6] or a complete eruption failure [7]. Eruption failure has been detected in either a single tooth or multiple teeth in both the primary and the permanent dentition and may also be partial or complete [8]. Apart from these factors, the eruption process of a permanent tooth could also be affected by genetic factors since numerous syndromes are found to give rise to similar clinical conditions where any genes responsible have already been discovered. Tooth eruption failure may be referred to as either primary retention or as secondary retention [4]. Diagnosis of the initial eruption discontinuation concerns the local failure of a tooth to erupt without necessitating the coexistence of any other local or systematic factor. There has been an association between initial tooth eruption failure and idiopathic eruption failure [7]. Secondary retention refers to teeth that, although existing in the oral cavity, have manifested as an incomplete eruption [4][8][4,8].3. Primary Retention

The phenomenon where molars cease to erupt before they emerge, without a physical barrier in the eruption path or as a consequence of an atypical location, is defined as primary retention. The alveolar support of a primarily retained molar, which does not resorb occlusally, is considered a normal barrier to the eruption path. Primary retention is similar to “unerupted” and “embedded” teeth [9]. In the event that the eruption of a permanent tooth is at least 2 years delayed compared to what is normally expected, primary retention should be a clinical entity to take into account. A radiographical follow-up of a minimum of 6 months is suggested as an initial control to determine whether the tooth is showing any eruptive movement or not [10]. The suggested radiographic methods include a periapical or even panoramic X-ray. Primary retention is the possible result of a disturbance in the dental follicle that does not succeed in initiating the metabolic events responsible for bone resorption in the eruption traject [11] (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

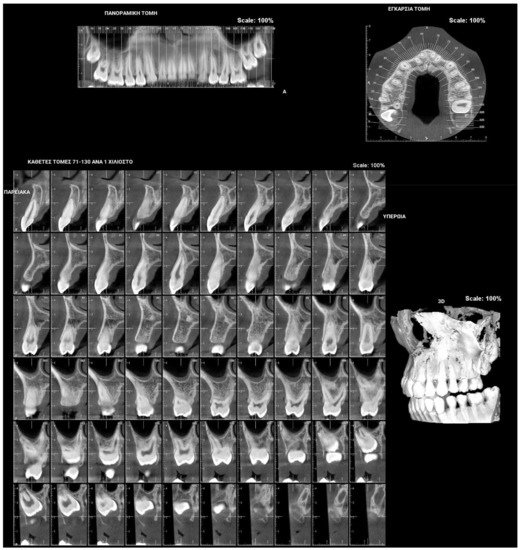

Figure 1.

Patient presenting eruption failure of the upper left second molar due to primary retention.

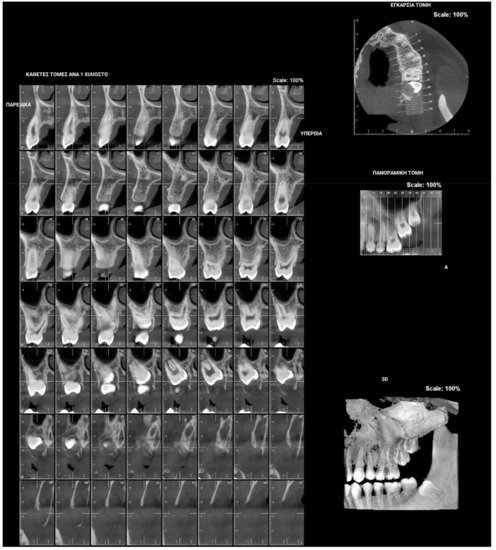

Figure 2.

Patient presenting eruption failure of the upper left second molar due to primary retention.

4. Secondary Retention

Secondary retention is the phenomenon where the eruption process stalls after the tooth has emerged without the evidence of a physical barrier in the eruption path or as a result of an abnormal position [12][13][12,13]. The etiology of secondary retention still remains unclear. It takes place when the tooth is still submerged or during the eruption process and always involves the first 2 mm of the radicular neck or the molar furcation region, i.e., the area that separates the attachment cord from the follicular sac and the anatomic neck, a region approximately 2 mm wide. As soon as ankylosis between the tooth and osseous support has taken place, not only the eruption but also the growth of the alveolar process in the influenced area is inhibited. The adjacent teeth carry on erupting and, as a consequence, the affected tooth is infraoccluded. This might lead to malocclusion, particularly after the inclination of the adjacent teeth towards the space [4].

Clinically secondary retention is often assumed when a molar is in infraocclusion at a time period when the tooth should typically be in occlusion. The probability of ankylosis can be recognized via a percussion test and radiographic examination of the periodontal ligament obliteration. Nevertheless, such diagnostic means do not always prove reliable due to the fact that the ankylosed area in secondary retention is usually difficult to observe [12] (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Patient after finishing the orthodontic treatment, presenting secondary retention due to fusion of the upper left second and third molars.

5. Primary Failure of Eruption (PFE)

“Primary Failure of Eruption” (PFE) is the clinical condition that is associated with failure during the tooth eruption process. Primary Failure of Eruption may present a number of the following characteristics: (1) a higher frequency of appearance in the posterior teeth area rather than in the anterior region, (2) the teeth may begin to erupt towards occlusion and stop erupting halfway through the process, (3) both primary and permanent molars may exhibit such a clinical condition, (4) this clinical condition may be spotted on either one side or both sides in the mouth, (5) permanent teeth with such a condition are likely to be ankylosed, (6) the application of any orthodontic force may result in tooth ankylosis, and (7) this clinical condition may be present without any relevant family history [7].

PFE attributes combine elements that resemble both primary and secondary retention (Figure 4). The diagnosis of PFE is impeded to a great extent by the complexity of this clinical picture (Figure 5 and Figure 6). It appears that this clinical condition has two different mechanisms or two different aspects of the same mechanism since the tooth may erupt in its initial position and thereafter stop its further eruption (a clinical condition known as secondary retention) [7][8][14][7,8,14], or the tooth may not be able to erupt at all [11]. In this context, a definitive diagnosis of PFE cannot easily be decided, as it is possible that PFE presents two separate mechanisms [11] or two independent manifestations of the same mechanism. Only if scholarswe were to examine an environment where genetic, pathological, and environmental factors—all factors potentially responsible for the discontinuation of the tooth’s eruption—are absent would a PFE diagnosis through a retrospective examination be possible.

Figure 4.

Patient’s orthopantomography presenting Primary Failure of Eruption in all four dental quadrants.

Figure 5.

Right photo of the female patient with PFE in bite relationship.

Figure 6.

Left photo of the same female patient depicted in

Figure 5

.