You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Conner Chen and Version 4 by Conner Chen.

Transient global amnesia (TGA) is a clinical syndrome characterized by the sudden onset of a temporary memory disorder with profound anterograde amnesia and a variable impairment of the past memory. Usually, the attacks are preceded by a precipitating event, last up to 24 h and are not associated with other neurological deficits. Diagnosis can be challenging because the identification of TGA requires the exclusion of some acute amnestic syndromes that occur in emergency situations and share structural or functional alterations of memory circuits.

- transient global amnesia

- amnesia

- hippocampus

1. Introduction

Transient global amnesia (TGA) is a clinical syndrome characterized by the sudden onset of profound anterograde amnesia and a less prominent retrograde memory impairment, lasting up to 24 h and not otherwise associated with other neurological deficits [1][2][3][4][1,2,3,4]. Headache, dizziness, and nausea are the most common accompanying complaints [4]. Even if the symptoms of TGA are quite characteristic, the differential diagnosis includes some acute amnestic syndromes, transient and totally reversible, that occur in emergency situations and share structural or functional alteration of memory circuits [5].

In recent years, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies have proven useful in confirming the diagnosis by identifying diffusion-weighted (DWI) lesions in the CA1 field of the hippocampal cornu ammonis [6]. However, the level of detection of the hippocampal DWI lesions in patients with TGA is highly time-dependent, so the maximum diagnostic yield of DWI lesions occurs 24 to 96 h after the onset of symptoms [7][8][9][7,8,9].

The annual incidence of TGA is on average at 3.4–10.4/100,000 and increases to 23.5/100,000 in subjects over 50 years of age [1][3][4][10][11][1,3,4,10,11]. The age at onset ranges from 61 to 67.3 years and the gender distribution is estimated at 50.7% females and 49.3% males [12][13][14][15][16][12,13,14,15,16].

2. TGA Roadmap

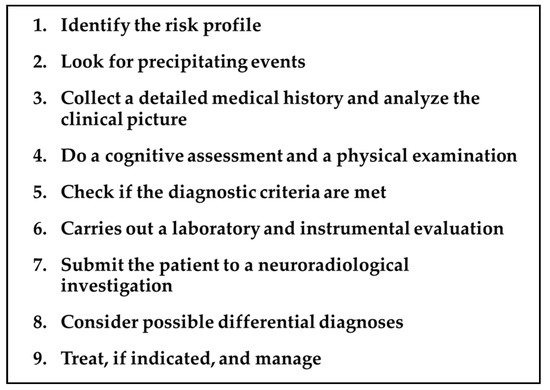

Addressing a patient with a suspected TGA requires a precise and detailed roadmap by the neurologist, keeping in mind the diagnostic criteria, the differential diagnosis, the mandatory and optional investigations, and the timing of each of these issues. The main steps of this proposed roadmap are summarized in Figure 1 and detailed in the following paragraphs.

Figure 1. TGA roadmap.

2.1. Risk Profile

Over the years, epidemiological studies have shown the association of TGA with some risk factors.-

Migraine history. In 2014 a large nationwide, population-based cohort study, enrolling 158.301 migraine patients and 158.301 healthy controls (HC), demonstrated that migraines are associated with an increased risk of TGA (incidence rate ratio =2.48, p = 0.002), particularly in female patients aged 40–60 years [17]. Noteworthy, in the same study, the subjects with a history of migraines had a significantly younger age of TGA onset (56.6 years) compared to the control group (61.4 years), suggesting that migraines could lead to an earlier age of disease onset [17]. In a recent analysis of the data obtained from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, which represents 20% of the US community hospitals for the years 1999–2008, patients with a diagnosis of migraines had 5.98 times greater odds of having TGA compared with patients without migraines [18]. In a more recent systematic review and meta-analysis, it was confirmed that there is a higher relative risk (RR) of TGA for migraine vs. non-migraine individuals [RR = 2.48, 95% confidence-interval (95% CI) = (1.32, 4.87)] [19].

-

Psychiatric comorbidity. Epidemiological studies suggest that some personality traits might be relevant to the etiology of the disease

Table 1. Diagnostic criteria for transient global amnesia (data from Hodges JR and Warlow CP 1990) [1][2][1,2].

| Main Diagnostic Features of TGA |

|---|

| Attack must be witnessed |

| There must be anterograde amnesia during the attack |

| Cognitive impairment limited to amnesia |

| No clouding of consciousness or loss of personal identity |

| No focal neurological signs/symptoms |

| No epileptic features |

| Attack must resolve within 24 h |

| No recent head injury or active epilepsy |

- [

- Emotional stress, (i.e., triggered by medical procedures, interpersonal conflict, birth/death announcement, and difficult/exhausting workday);

- Physical effort, (i.e., gardening, housework, and sawing wood);

- Acute pain;

- Water contact/temperature change, (i.e., hot bath/shower and cold swim);

- Reduction of executive function

2.4.2. Preserved Cognitive Functions in TGA

- Short-term memory

-

Semantic memory

-

Implicit and procedural memory

2.5. Diagnostic Criteria

The clinical diagnosis of TGA is confirmed by applying the criteria provided by Hodges and Warlow [2] (Table 1). Although these criteria still remain valid in clinical practice, some additions are necessary. The possibility of associated retrograde amnesia is not included in the criteria, but it is well recognized that patients with TGA can have some degree of retrograde amnesia during the episode [3][49][3,49]. As mentioned earlier, several studies show the involvement of other cognitive functions, such as executive functions or visuo-perceptual abilities [3][44][3,44]. Furthermore, the criteria currently adopted do not allow people to exclude some acute amnestic syndromes that occur in emergency situations, such as ischemic or hypoxic events, migraines, toxic amnesia, etc.2.6. Laboratory Tests and Instrumental Evaluation

No laboratory investigations can actually confirm the diagnosis of TGA. However, a laboratory diagnostic workup should include at least glucose and electrolyte dosage. Hypoglycemia can result in an amnestic deficit and might be considered a differential diagnosis if the patient is diabetic. Alcohol level and a toxicology screen should also be reviewed (see Section 2.8).2.6.1. Electroencephalography (EEG)

During and after typical TGA episodes, EEG findings have been reported to be normal [11][50][51][11,50,51]. EEG should be considered if there are features suggestive of repetitive or seizure-like etiology. Temporal lobe or complex partial seizures might present in fact as transient epileptic amnesia (TEA), particularly when repetitive episodes of transient amnesia occur [52][52] (see Section 2.8).2.6.2. Transthoracic Echocardiography

Echocardiography may be indicated to evaluate left ventricular ejection fraction and septal hypertrophy in TGA patients with elevated blood pressure on admission. In fact, septal hypertrophy, defined as the presence of an increase in the thickness of the septum (women >9 mm, men >10 mm), is considered a possible indicator of chronic hypertension [25]. Therefore, transthoracic echocardiography can help differentiate chronic hypertension from acute hypertension and support the indication of antihypertensive drugs in patients with previously unknown hypertension.2.7. Neuroimaging

Although the diagnosis of TGA is largely clinical and of exclusion, neuroimaging can provide an important diagnostic contribution.2.7.1. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

In 1998, Strupp et al. first described high-signal hippocampal lesions using DWI MRI [53]. Since then, the role of MRI in the diagnosis of TGA has been largely confirmed and clarified [6][8][54][55][56][57][6,8,54,55,56,57]. It has been demonstrated, in fact, that the detection rate of hippocampal lesions in TGA can be improved by up to 85% with optimized MRI parameters and by acknowledging the time course of the lesion [7]. The following are the main MRI findings in patients with TGA (Table 2):Table 2.

MRI findings and parameters in TGA.

| Main MRI Issues in TGA |

|---|

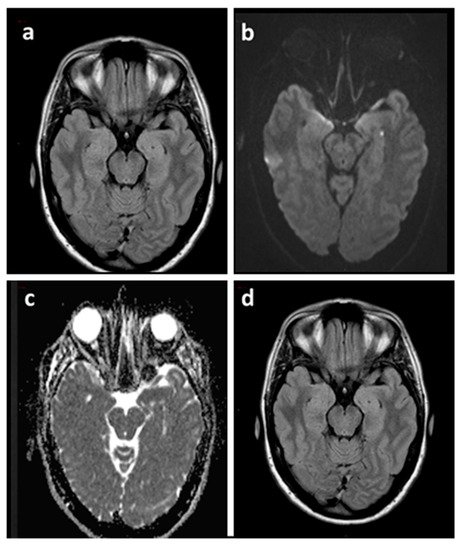

- Almost all lesions can be selectively found in the area corresponding to the CA1 sector (Sommer sector) of the hippocampal cornu ammonis [6][7][8][6,7,8] (Figure 2).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

DWI: Diffusion Weighted Imaging; MR: Magnetic Resonance; T: Tesla; TGA: Transient Global Amnesia; FLAIR: Fluid Attenuated Inversion Recovery.

- Lesions can be single or multiple and vary in size from 1 to 5 mm

- [7].

- In a recent meta-analysis of 1732 patients with TGA the pooled incidence of right, left, and bilateral hippocampal lesions were 37% (95% CI, 29–44%), 42% (95% CI, 39–46%), and 25% (95% CI, 20–30%), respectively [9].

- In the same study, DWI with a slice thickness ≤3 mm showed a higher diagnostic yield than DWI with a slice thickness >3 mm [63% (95% CI, 53–72%) vs. 26% (95% CI, 16–40%), p < 0.01] and there was no significant difference in the diagnostic yield between 3 T and 1.5 T imaging [pooled diagnostic yield, 31% (95% CI, 25–38%) vs. 24% (95% CI, 14–37%), p = 0.31)] [9].

- Neuroimaging data have shown that the level of detection of hippocampal DWI lesions in patients with TGA is highly time-dependent: DWI performed at an interval between 24 and 96 h after symptom onset has a higher diagnostic yield than DWI performed within 24 h or later than 96 h [7][8][7[9],8,9].

- Focal hippocampal DWI lesions generally resolve 7–10 days after onset of TGA, with no long-term structural changes [58]. This complete reversibility of DWI hippocampal hyperintensity without structural sequelae, as confirmed by the lack of persistent signal change on T2-weighted or FLAIR sequences, does not conform to the time course of classic ischemic lesions [9]

- 28][6,7,10,12,20,26,27,28].

- ,

- ,

- ]. Pantoni et al. found that TGA patients had a significantly higher percentage of depression or anxiety disorder, as well as phobic traits in comparison with patients who have had a transient ischemic attack (TIA) or with HC [13]. Additionally, a significantly higher percentage of TGA subjects (33.3%) reported a family history of psychiatric disease as compared with TIA subjects (13.7%) [13]. Other authors have found an increased frequency of psychological or emotional instability and a tendency to feel guilty among patients experiencing TGA events [12][22][12,22].

-

Vascular risk profile. A retrospective case–control study comparing 293 TGA patients to 632 patients with TIA and 293 age- and sex-matched HC showed a significantly higher prevalence of hyperlipidemia and ischemic heart disease in TGA patients when compared to TIA patients or HC [23]. Conversely, diabetes mellitus was associated with a significantly reduced occurrence of TGA [23]. In a systematic review of observational studies examining the relationship between the conventional cardiovascular risk factors and TGA, there was evidence of a potential association between severe hypertension (defined according to a 160/95 mmHg cut-off) and TGA [24]. Diabetes mellitus (stronger evidence) and current smoking (limited evidence) were found to exert a protective effect [24]. Furthermore, the role of hypertension in TGA was extensively evaluated in a recent analysis that compared the cardiovascular risk profile of 277 patients with TGA to 216 patients with acute ischemic stroke [25]. In theirs study, patients with TGA had significantly higher systolic and diastolic blood pressure at admission than stroke patients, but lower signs of chronic hypertension, as measured by the extent of cerebral microangiopathy and degree of septal hypertrophy in transthoracic echocardiography [25].

2.2. Precipitating Events

In a retrospective cohort study of 203 TGA cases from a single center in Buenos Aires, 66% of patients referred to a precipitating event for TGA; most often a Valsalva maneuver (41%) [29]. Quinette et al. found a different profile of precipitating events between the sexes: in men, the TGA episode occurred more frequently after a strenuous physical event, whereas, in women, TGA was often precipitated by an emotional event [12]. The same sex-related differences in the precipitating event profile were found in a recent retrospective observational analysis of 389 patients with TGA [28]. In theirs study, emotional triggers were experienced more often by women (37.2% vs. 22.8%, p = 0.003), while physical stressors were more frequent in men (30.7% vs. 41.1%), p = 0.035). In the same study, the emotional trigger was often classified as interpersonal conflict (42.7%) [28]. However, emotional and psychological distress are frequent precipitating events in patients with TGA and are often associated with phobic personality traits [4][12][24][27][30][4,12,24,27,30].2.3. Clinical Picture

The clinical presentation of the TGA is characterized by the sudden onset of temporary memory impairment with a prominent inability to form new memories (anterograde amnesia) and a variable impairment of the past memory (retrograde amnesia) [1][2][3][4][1,2,3,4]. Typically, patients do not fix any novel information, e.g., the treating physician or why they were brought to the hospital, so they repeatedly ask questions, such as, “Why are we here?”, “What time is it?”, or “How did I get here?” [3][31][3,31]. Patients remain alert, fully communicative, and keep intact higher cortical functions such as language, calculations, visuospatial skills, reasoning and abstract thinking [32]. Thus, during the episode, they maintain personal and family members’ knowledge, preserve remote memories, and perform previously learned activities, (e.g., driving without impairment) [3][33][3,33]. Mild vegetative symptoms, such as headache, nausea, and dizziness may occur during the attack [31]. Chills or hot flushes, fear of dying, cold extremities, paraesthesia, emotionalism, trembling, chest pain, and sweating have also been reported in the literature [4][12][4,12]. A recent study on 665 patients determining a chronological pattern of TGA occurrence identified a significant circadian rhythm with a major peak in the morning between 10 and 11 am and a secondary peak between 4 and 5 pm [34]. TGA typically lasts a few hours, often 4 to 6 h, and always less than 24 h [3][12][35][3,12,35]. Short-duration TGA episodes (<1 h) are not uncommon, ranging between 9–32% of cases [1][3][36][1,3,36]. Many studies have shown complete recovery of memory functioning several months after an episode of TGA [6][30][37][38][39][40][41][6,30,37,38,39,40,41]. However, some authors have reported the persistence of a subclinical impairment of memory functions for months after the acute episode [7][42][43][44][45][46][7,42,43,44,45,46]. Because patients cannot store new memories during the episode, they will have a permanent memory gap for the duration of the attack.2.4. Cognitive Evaluation and Physical Examination during TGA

2.4.1. Main Cognitive Alterations

- .

- T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences allow people to identify and evaluate the extent of cerebral microangiopathy in order to provide a measure of the presence and degree of chronic hypertension

- [

- 25

- ]

- . In this way, these sequences can provide useful indications for a more rigorous antihypertensive drug treatment in patients with chronic hypertension and can help to calculate the risk of subsequent TGA recurrence in patients without microangiopathic alterations

- (for details see paragraph 3.1 of this review).

-

Reduction in anterograde episodic long-term memory

- Complementary imaging studies combining MRI and focal MR spectroscopy (MRS) of CA1 DWI/T2 lesions revealed a transient lactate peak without changes of N-acetyl-aspartate (NAA) and creatine (Cr), indicating acute metabolic stress of CA-1 neurons during TGA

- [

- 58

- ]

- . The lactate peak was detected only in the DWI lesion and not in the perifocal tissue, suggesting that the metabolic changes in CA1 neurons were highly focal and not suggestive of a globally altered metabolic status in the hippocampus

- [

- 58

- ][58] (see Part I of this review for the pathogenetic implications of these neuroradiological findings).

-

Partial loss of retrograde episodic long-term memory

Figure 2. Brain MRI of a TGA patient acquired 48 h after the episode (a–c) and at three months (d). Axial FLAIR sequence (a) showing both hippocampi without signal abnormalities corresponding to the punctate DWI hyperintensity (b) with ADC hypointensity (c) in the left hippocampus. Axial FLAIR sequence at three months (d) confirmed the absence of signal abnormalities. ADC: Apparent Diffusion Coefficient.

2.7.2. Positron Emission Tomography (PET) and Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT)

Many studies have investigated quantitative changes in regional cerebral glucose, oxygen metabolism, or cerebrovascular blood flow during TGA attacks by the use of PET or SPECT. However, these studies have provided controversial results regarding the type and site of the findings.- Most of the studies showed mesiotemporal alterations of perfusion or metabolism during the acute or post-acute phase of TGA [7][47][59][60][61],60[62]66,61[63,62][64],63][67,64[65][][68,65][69][70][7,47,59,66,67,68,69,70].

- Many studies noted concomitant (decreased or increased) changes in cerebral blood flow in other anatomical structures, such as unilateral or bilateral thalamic, prefrontal, frontal, amygdalin, striatal, cerebellar, occipital, precentral, and postcentral areas [7][47][59][60][61][62][71][76][77][78][7,4772],59[73],60[,61,62,71,72,7374],74[75],75[,76,77,78].

- Several studies reported mono or bilateral hypoperfusion in the anatomical structures above mentioned [60][65][78][79]][60,65[,7880],79[81],80[,8182,82].

- On the other hand, some studies showed increased perfusion in various limbic regions such as the hippocampus, amygdala, and thalamus [72][74][83][84][72,74,83,84].

- In some patients, hypoperfusion or hyperperfusion has been reported in the hippocampus, amygdala, and thalamus only of the left cerebral hemisphere [74][83][84][85][74,83,84,85].

- Finally, in some studies, no mesiotemporal or cerebral changes were detected [7][85][86][7,85,86].