RNA viruses pose the greatest threat to public health, with the potential to cause global catastrophic biological events, necessitating the identification of attributes of these microorganisms so as to open up new therapeutic and prophylactic avenues. We have come across many viral outbreaks, which put vulnerable individuals at high risk but differ in the vectors of transmission, rates of fatality and transmissibility. Certain viruses such as Dengue and Zika require an intermediate host for their transmission, while diseases such as COVID-19 and Ebola Virus Disease spread directly from human to human. COVID-19, which resulted in the highest number of deaths globally, has triggered a lot of research into the mechanisms of immune responses generated by RNA viruses and also into the various approaches for combating such viral outbreaks. The experiences with the Ebola outbreak in West Africa have provided valuable lessons to the global community in shaping the initial and quick management strategies for COVID-19.

- COVID-19

- Ebola

- immune response

- vaccine

- SARS-CoV-2

1. A Comparative Look at the Pathogenic RNA Viruses—SARS-CoV-2 and Ebola Virus

2. Host Anti-Viral Immune Response in SARS-CoV-2 and EBOV Infections

2.1. Defining Innate Immunity

2.2. Alterations in Adaptive Immune Response

2.2.1. Overview of the Humoral Immune Response

2.2.2. Landscapes in T-Cell-Mediated Immune Response

2.2.3. Long Term Anti-Viral Immunity

2.3. Risk Factors That May Influence the Immune Mechanism

References

- Cascella, M.; Rajnik, M.; Aleem, A.; Dulebohn, S.; Di Napoli, R. Features, Evaluation and Treatment Coronavirus (COVID-19); StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554776/ (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Kimble, J.B.; Malherbe, D.C.; Meyer, M.; Gunn, B.M.; Karim, M.M.; Ilinykh, P.A.; Iampietro, M.; Mohamed, K.S.; Negi, S.; Gilchuk, P.; et al. Antibody-Mediated Protective Mechanisms Induced by a Trivalent Parainfluenza Virus-Vectored Ebolavirus Vaccine. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e01845-18.

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.-L.; Wang, X.-G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.-R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.-L.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273.

- Kamorudeen, R.T.; Adedokun, K.A.; Olarinmoye, A.O. Ebola outbreak in West Africa, 2014–2016: Epidemic timeline, differential diagnoses, determining factors, and lessons for future response. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 956–962.

- Zhou, L.; Ayeh, S.K.; Chidambaram, V.; Karakousis, P.C. Modes of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and evidence for preventive behavioral interventions. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 496.

- Lin, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhong, P.; Hou, B.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J. A clinical staging proposal of the disease course over time in non-severe patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10681.

- Bixler, S.L.; Goff, A.J. The Role of Cytokines and Chemokines in Filovirus Infection. Viruses 2015, 7, 5489–5507.

- Mokhtari, T.; Hassani, F.; Ghaffari, N.; Ebrahimi, B.; Yarahmadi, A.; Hassanzadeh, G. COVID-19 and multiorgan failure: A narrative review on potential mechanisms. Histochem. J. 2020, 51, 613–628.

- Elliott, L.H.; Sanchez, A.; Holloway, B.P.; Kiley, M.P.; McCormick, J.B. Ebola protein analyses for the determination of genetic organization. Arch. Virol. 1993, 133, 423–436.

- Sanchez, A.; Kiley, M.P.; Holloway, B.P.; Auperin, D.D. Sequence analysis of the Ebola virus genome: Organization, genetic elements, and comparison with the genome of Marburg virus. Virus Res. 1993, 29, 215–240.

- Takamatsu, Y.; Kolesnikova, L.; Becker, S. Ebola virus proteins NP, VP35, and VP24 are essential and sufficient to mediate nucleocapsid transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 1075–1080.

- Feldmann, H.; Sprecher, A.; Geisbert, T.W. Ebola. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1832–1842.

- Genomic Characterization of a Novel SARS-CoV-2—PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32300673/ (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Premkumar, L.; Segovia-Chumbez, B.; Jadi, R.; Martinez, D.R.; Raut, R.; Markmann, A.; Cornaby, C.; Bartelt, L.; Weiss, S.; Park, Y.; et al. The receptor binding domain of the viral spike protein is an immunodominant and highly specific target of antibodies in SARS-CoV-2 patients. Sci. Immunol. 2020, 5, eabc8413.

- Shang, J.; Wan, Y.; Luo, C.; Ye, G.; Geng, Q.; Auerbach, A.; Li, F. Cell entry mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 11727–11734.

- Lee, J.E.; Saphire, E.O. Ebolavirus glycoprotein structure and mechanism of entry. Future Virol. 2009, 4, 621–635.

- Mohan, G.S.; Ye, L.; Li, W.; Monteiro, A.; Lin, X.; Sapkota, B.; Pollack, B.P.; Compans, R.W.; Yang, C. Less Is More: Ebola Virus Surface Glycoprotein Expression Levels Regulate Virus Production and Infectivity. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 1205–1217.

- Furuyama, W.; Shifflett, K.; Feldmann, H.; Marzi, A. The Ebola virus soluble glycoprotein contributes to viral pathogenesis by activating the MAP kinase signaling pathway. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009937. Available online: https://journals.plos.org/plospathogens/article?id=10.1371/journal.ppat.1009937 (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Khataby, K.; Kasmi, Y.; Hammou, R.A.; Laasri, F.E.; Boughribi, S.; Ennaji, M.M. Ebola Virus’s Glycoproteins and Entry Mechanism. In Ebola; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2016.

- Li, R.-T.; Qin, C.-F. Expression pattern and function of SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2. Biosaf. Health 2021, 3, 312–318.

- Brunton, B.; Rogers, K.; Phillips, E.K.; Brouillette, R.B.; Bouls, R.; Butler, N.S.; Maury, W. TIM-1 serves as a receptor for Ebola virus in vivo, enhancing viremia and pathogenesis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0006983.

- Kondratowicz, A.S.; Lennemann, N.J.; Sinn, P.L.; Davey, R.A.; Hunt, C.L.; Moller-Tank, S.; Meyerholz, D.K.; Rennert, P.; Mullins, R.F.; Brindley, M.; et al. T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 1 (TIM-1) is a receptor for Zaire Ebolavirus and Lake Victoria Marburgvirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 8426–8431.

- Bohan, D.; Van Ert, H.; Ruggio, N.; Rogers, K.J.; Badreddine, M.; Briseño, J.A.A.; Elliff, J.M.; Chavez, R.A.R.; Gao, B.; Stokowy, T.; et al. Phosphatidylserine receptors enhance SARS-CoV-2 infection. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009743.

- Nanbo, A.; Kawaoka, Y. Molecular Mechanism of Externalization of Phosphatidylserine on the Surface of Ebola Virus Particles. DNA Cell Biol. 2019, 38, 115–120.

- Acciani, M.D.; Mendoza, M.F.L.; Havranek, K.E.; Duncan, A.M.; Iyer, H.; Linn, O.L.; Brindley, M.A. Ebola Virus Requires Phosphatidylserine Scrambling Activity for Efficient Budding and Optimal Infectivity. J. Virol. 2021, 95, JVI0116521.

- Nanbo, A.; Maruyama, J.; Imai, M.; Ujie, M.; Fujioka, Y.; Nishide, S.; Takada, A.; Ohba, Y.; Kawaoka, Y. Ebola virus requires a host scramblase for externalization of phosphatidylserine on the surface of viral particles. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1006848. Available online: https://journals.plos.org/plospathogens/article?id=10.1371/journal.ppat.1006848 (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Younan, P.; Iampietro, M.; Nishida, A.; Ramanathan, P.; Santos, R.I.; Dutta, M.; Lubaki, N.M.; Koup, R.A.; Katze, M.G.; Bukreyev, A. Ebola Virus Binding to Tim-1 on T Lymphocytes Induces a Cytokine Storm. mBio 2017, 8, e00845-17.

- Kennedy, J.R. Phosphatidylserine’s role in Ebola’s inflammatory cytokine storm and hemorrhagic consumptive coagulopathy and the therapeutic potential of annexin V. Med. Hypotheses 2019, 135, 109462.

- Roncato, R.; Angelini, J.; Pani, A.; Talotta, R. Lipid rafts as viral entry routes and immune platforms: A double-edged sword in SARS-CoV-2 infection? Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2022, 1867, 159140.

- Jin, C.; Che, B.; Guo, Z.; Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Wu, W.; Wang, S.; Li, D.; Cui, Z.; Liang, M. Single virus tracking of Ebola virus entry through lipid rafts in living host cells. Biosaf. Health 2020, 2, 25–31.

- Yang, Q.; Shu, H.-B. Chapter One—Deciphering the pathways to antiviral innate immunity and inflammation. In Advances in Immunology; Dong, C., Jiang, Z., Eds.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 145, pp. 1–36.

- Tay, M.Z.; Poh, C.M.; Rénia, L.; Macary, P.A.; Ng, L.F.P. The trinity of COVID-19: Immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 363–374.

- Jain, S.; Khaiboullina, S.F.; Baranwal, M. Immunological Perspective for Ebola Virus Infection and Various Treatment Measures Taken to Fight the Disease. Pathogens 2020, 9, 850.

- Cron, R.Q.; Caricchio, R.; Chatham, W.W. Calming the cytokine storm in COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1674–1675.

- Rubsamen, R.; Burkholz, S.; Massey, C.; Brasel, T.; Hodge, T.; Wang, L.; Herst, C.; Carback, R.; Harris, P. Anti-IL-6 Versus Anti-IL-6R Blocking Antibodies to Treat Acute Ebola Infection in BALB/c Mice: Potential Implications for Treating Cytokine Release Syndrome. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 574703. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fphar.2020.574703 (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Acharya, D.; Liu, G.; Gack, M.U. Dysregulation of type I interferon responses in COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 397–398.

- Zhang, Q.; Bastard, P.; Liu, Z.; Le Pen, J.; Moncada-Velez, M.; Chen, J.; Ogishi, M.; Sabli, I.K.D.; Hodeib, S.; Korol, C.; et al. Inborn errors of type I IFN immunity in patients with life-threatening COVID-19. Science 2020, 370, eabd4570.

- Lubaki, N.M.; Younan, P.; Santos, R.I.; Meyer, M.; Iampietro, M.; Koup, R.A.; Bukreyev, A. The Ebola Interferon Inhibiting Domains Attenuate and Dysregulate Cell-Mediated Immune Responses. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1006031.

- Lever, M.S.; Piercy, T.J.; Steward, J.A.; Eastaugh, L.; Smither, S.J.; Taylor, C.; Salguero, F.J.; Phillpotts, R.J. Lethality and pathogenesis of airborne infection with filoviruses in A129 α/β −/− interferon receptor-deficient mice. J. Med. Microbiol. 2012, 61, 8–15.

- Comer, J.E.; Escaffre, O.; Neef, N.; Brasel, T.; Juelich, T.L.; Smith, J.K.; Smith, J.; Kalveram, B.; Perez, D.D.; Massey, S.; et al. Filovirus Virulence in Interferon α/β and γ Double Knockout Mice, and Treatment with Favipiravir. Viruses 2019, 11, 137.

- Frontiers | Neutrophil Activation in Acute Hemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome Is Mediated by Hantavirus-Infected Microvascular Endothelial Cells | Immunology. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2018.02098/full (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Hasan, A.; Al-Ozairi, E.; Al-Baqsumi, Z.; Ahmad, R.; Al-Mulla, F. Cellular and Humoral Immune Responses in Covid-19 and Immunotherapeutic Approaches. ImmunoTargets Ther. 2021, 10, 63–85.

- Eisfeld, A.J.; Halfmann, P.J.; Wendler, J.P.; Kyle, J.E.; Burnum-Johnson, K.E.; Peralta, Z.; Maemura, T.; Walters, K.B.; Watanabe, T.; Fukuyama, S.; et al. Multi-platform ’Omics Analysis of Human Ebola Virus Disease Pathogenesis. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 22, 817–829.e8.

- Sander, W.J.; O’Neill, H.; Pohl, C.H. Prostaglandin E2 As a Modulator of Viral Infections. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 89.

- Ricke-Hoch, M.; Stelling, E.; Lasswitz, L.; Gunesch, A.P.; Kasten, M.; Zapatero-Belinchón, F.J.; Brogden, G.; Gerold, G.; Pietschmann, T.; Montiel, V.; et al. Impaired immune response mediated by prostaglandin E2 promotes severe COVID-19 disease. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255335.

- Jayaprakash, A.D.; Ronk, A.J.; Prasad, A.N.; Covington, M.F.; Stein, K.R.; Schwarz, T.M.; Hekmaty, S.; Fenton, K.A.; Geisbert, T.W.; Basler, C.F.; et al. Ebola and Marburg virus infection in bats induces a systemic response. bioRxiv 2020.

- Levi, M.; de Jonge, E.; van der Poll, T.; Cate, H.T. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. Thromb Haemost 1999, 82, 695–705.

- Eslamifar, Z.; Behzadifard, M.; Soleimani, M.; Behzadifard, S. Coagulation abnormalities in SARS-CoV-2 infection: Overexpression tissue factor. Thromb. J. 2020, 18, 38.

- Geisbert, T.W.; Young, H.A.; Jahrling, P.B.; Davis, K.J.; Kagan, E.; Hensley, L. Mechanisms Underlying Coagulation Abnormalities in Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever: Overexpression of Tissue Factor in Primate Monocytes/Macrophages Is a Key Event. J. Infect. Dis. 2003, 188, 1618–1629.

- Adaptive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19—PMC. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7803150/ (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Long, Q.-X.; Liu, B.-Z.; Deng, H.-J.; Wu, G.-C.; Deng, K.; Chen, Y.-K.; Liao, P.; Qiu, J.-F.; Lin, Y.; Cai, X.-F.; et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 845–848.

- Colavita, F.; Biava, M.; Castilletti, C.; Lanini, S.; Miccio, R.; Portella, G.; Vairo, F.; Ippolito, G.; Capobianchi, M.R.; Di Caro, A.; et al. Inflammatory and Humoral Immune Response during Ebola Virus Infection in Survivor and Fatal Cases Occurred in Sierra Leone during the 2014–2016 Outbreak in West Africa. Viruses 2019, 11, 373.

- McElroy, A.K.; Akondy, R.S.; Davis, C.W.; Ellebedy, A.H.; Mehta, A.K.; Kraft, C.S.; Lyon, G.M.; Ribner, B.S.; Varkey, J.; Sidney, J.; et al. Human Ebola virus infection results in substantial immune activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 4719–4724.

- Zinkernagel, R.M.; Hengartner, H. Protective ‘immunity’ by pre-existent neutralizing antibody titers and preactivated T cells but not by so-called ‘immunological memory’. Immunol. Rev. 2006, 211, 310–319.

- Flyak, A.I.; Shen, X.; Murin, C.D.; Turner, H.L.; David, J.A.; Fusco, M.L.; Lampley, R.; Kose, N.; Ilinykh, P.A.; Kuzmina, N.; et al. Cross-Reactive and Potent Neutralizing Antibody Responses in Human Survivors of Natural Ebolavirus Infection. Cell 2016, 164, 392–405.

- Wang, X.; Guo, X.; Xin, Q.; Pan, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, J.; Chu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Q. Neutralizing Antibody Responses to Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 in Coronavirus Disease 2019 Inpatients and Convalescent Patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 2688–2694.

- Non-Neutralizing Antibodies from a Marburg Infection Survivor Mediate Protection by Fc-Effector Functions and by Enhancing Efficacy of Other Antibodies—ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S193131282030189X (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Gunn, B.M.; Alter, G. Modulating Antibody Functionality in Infectious Disease and Vaccination. Trends Mol. Med. 2016, 22, 969–982.

- A Fc-Enhanced NTD-binding Non-Neutralizing Antibody Delays Virus Spread and Synergizes with a nAb to Protect Mice from Lethal SARS-CoV-2 Infection—ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211124722000894 (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Ren, L.; Zhang, L.; Chang, D.; Wang, J.; Hu, Y.; Chen, H.; Guo, L.; Wu, C.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; et al. The kinetics of humoral response and its relationship with the disease severity in COVID-19. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 780.

- Aydillo, T.; Rombauts, A.; Stadlbauer, D.; Aslam, S.; Abelenda-Alonso, G.; Escalera, A.; Amanat, F.; Jiang, K.; Krammer, F.; Carratala, J.; et al. Immunological imprinting of the antibody response in COVID-19 patients. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3781.

- Ellebedy, A.H.; Jackson, K.; Kissick, H.T.; Nakaya, H.; Davis, C.W.; Roskin, K.M.; McElroy, A.; Oshansky, C.M.; Elbein, R.; Thomas, S.; et al. Defining antigen-specific plasmablast and memory B cell subsets in human blood after viral infection or vaccination. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 1226–1234.

- Frontiers | Vascular Damage, Thromboinflammation, Plasmablast Activation, T-Cell Dysregulation and Pathological Histiocytic Response in Pulmonary Draining Lymph Nodes of COVID-19 | Immunology. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2021.763098/full (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- De Biasi, S.; Tartaro, D.L.; Meschiari, M.; Gibellini, L.; Bellinazzi, C.; Borella, R.; Fidanza, L.; Mattioli, M.; Paolini, A.; Gozzi, L.; et al. Expansion of plasmablasts and loss of memory B cells in peripheral blood from COVID-19 patients with pneumonia. Eur. J. Immunol. 2020, 50, 1283–1294. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/eji.202048838 (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- McElroy, A.K.; Akondy, R.S.; Mcllwain, D.R.; Chen, H.; Bjornson-Hooper, Z.; Mukherjee, N.; Mehta, A.K.; Nolan, G.; Nichol, S.T.; Spiropoulou, C.F. Immunologic timeline of Ebola virus disease and recovery in humans. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e137260.

- Gaebler, C.; Wang, Z.; Lorenzi, J.C.C.; Muecksch, F.; Finkin, S.; Tokuyama, M.; Cho, A.; Jankovic, M.; Schaefer-Babajew, D.; Oliveira, T.Y.; et al. Evolution of antibody immunity to SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2021, 591, 639–644.

- Dan, J.M.; Mateus, J.; Kato, Y.; Hastie, K.M.; Yu, E.D.; Faliti, C.E.; Grifoni, A.; Ramirez, S.I.; Haupt, S.; Frazier, A.; et al. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science 2021, 371, eabf4063.

- Williamson, L.E.; Flyak, A.I.; Kose, N.; Bombardi, R.; Branchizio, A.; Reddy, S.; Davidson, E.; Doranz, B.J.; Fusco, M.L.; Saphire, E.O.; et al. Early Human B Cell Response to Ebola Virus in Four, U.S. Survivors of Infection. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e01439-18.

- Bebell, L.M.; Oduyebo, T.; Riley, L.E. Ebola virus disease and pregnancy: A review of the current knowledge of Ebola virus pathogenesis, maternal, and neonatal outcomes. Birth Defects Res. 2017, 109, 353–362. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/bdra.23558 (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Corti, D.; Misasi, J.; Mulangu, S.; Stanley, D.A.; Kanekiyo, M.; Wollen, S.; Ploquin, A.; Doria-Rose, N.A.; Staupe, R.P.; Bailey, M.; et al. Protective monotherapy against lethal Ebola virus infection by a potently neutralizing antibody. Science 2016, 351, 1339–1342.

- Natesan, M.; Jensen, S.M.; Keasey, S.L.; Kamata, T.; Kuehne, A.I.; Stonier, S.W.; Lutwama, J.J.; Lobel, L.; Dye, J.M.; Ulrich, R.G. Human Survivors of Disease Outbreaks Caused by Ebola or Marburg Virus Exhibit Cross-Reactive and Long-Lived Antibody Responses. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2016, 23, 717–724.

- Rimoin, A.W.; Lu, K.; Bramble, M.S.; Steffen, I.; Doshi, R.H.; Hoff, N.A.; Mukadi, P.; Nicholson, B.P.; Alfonso, V.H.; Olinger, G.; et al. Ebola Virus Neutralizing Antibodies Detectable in Survivors of the Yambuku, Zaire Outbreak 40 Years after Infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 217, 223–231.

- Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies Persist for up to 13 Months and Reduce Risk of Reinfection | medRxiv. Available online: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.05.07.21256823v3 (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Ebola Virus Antibody Decay–Stimulation in a High Proportion of Survivors | Nature. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-020-03146-y (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Diallo, M.S.K.; Ayouba, A.; Keita, A.K.; Thaurignac, G.; Sow, M.S.; Kpamou, C.; Barry, T.A.; Msellati, P.; Etard, J.-F.; Peeters, M.; et al. Temporal evolution of the humoral antibody response after Ebola virus disease in Guinea: A 60-month observational prospective cohort study. Lancet Microbe 2021, 2, e676–e684.

- Woolsey, C.; Geisbert, T.W. Antibodies periodically wax and wane in survivors of Ebola. Nature 2021, 590, 397–398.

- Klein, S.L.; Flanagan, K.L. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 626–638.

- Tsverava, L.; Chitadze, N.; Chanturia, G.; Kekelidze, M.; Dzneladze, D.; Imnadze, P.; Gamkrelidze, A.; Lagani, V.; Khuchua, Z.; Solomonia, R.; et al. Antibody profiling reveals gender differences in response to SARS-COVID-2 infection. AIMS Allergy Immunol. 2022, 6, 6–13.

- Gallian, P.; Pastorino, B.; Morel, P.; Chiaroni, J.; Ninove, L.; de Lamballerie, X. Lower prevalence of antibodies neutralizing SARS-CoV-2 in group O French blood donors. Antivir. Res. 2020, 181, 104880.

- Binagwaho, A.; Mathewos, K. Infectious disease outbreaks highlight gender inequity. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 361–362.

- Adachi, E.; Saito, M.; Nagai, H.; Ikeuchi, K.; Koga, M.; Tsutsumi, T.; Yotsuyanagi, H. Transient depletion of T cells during COVID-19 and seasonal influenza in people living with HIV. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 1789–1791. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jmv.27543 (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Wauquier, N.; Becquart, P.; Padilla, C.; Baize, S.; Leroy, E.M. Human Fatal Zaire Ebola Virus Infection Is Associated with an Aberrant Innate Immunity and with Massive Lymphocyte Apoptosis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2010, 4, e837. Available online: https://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0000837 (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Shrotri, M.; van Schalkwyk, M.C.I.; Post, N.; Eddy, D.; Huntley, C.; Leeman, D.; Rigby, S.; Williams, S.V.; Bermingham, W.H.; Kellam, P.; et al. T cell response to SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245532.

- Lucas, C.; Wong, P.; Klein, J.; Castro, T.B.R.; Silva, J.; Sundaram, M.; Ellingson, M.K.; Mao, T.; Oh, J.E.; Israelow, B.; et al. Longitudinal analyses reveal immunological misfiring in severe COVID-19. Nature 2020, 584, 463–469.

- André, S.; Picard, M.; Cezar, R.; Roux-Dalvai, F.; Alleaume-Butaux, A.; Soundaramourty, C.; Cruz, A.S.; Mendes-Frias, A.; Gotti, C.; Leclercq, M.; et al. T cell apoptosis characterizes severe Covid-19 disease. Cell Death Differ. 2022, 1–14.

- Iampietro, M.; Younan, P.; Nishida, A.; Dutta, M.; Lubaki, N.M.; Santos, R.I.; Koup, R.A.; Katze, M.G.; Bukreyev, A. Ebola virus glycoprotein directly triggers T lymphocyte death despite of the lack of infection. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006397. Available online: https://journals.plos.org/plospathogens/article?id=10.1371/journal.ppat.1006397 (accessed on 26 May 2022).

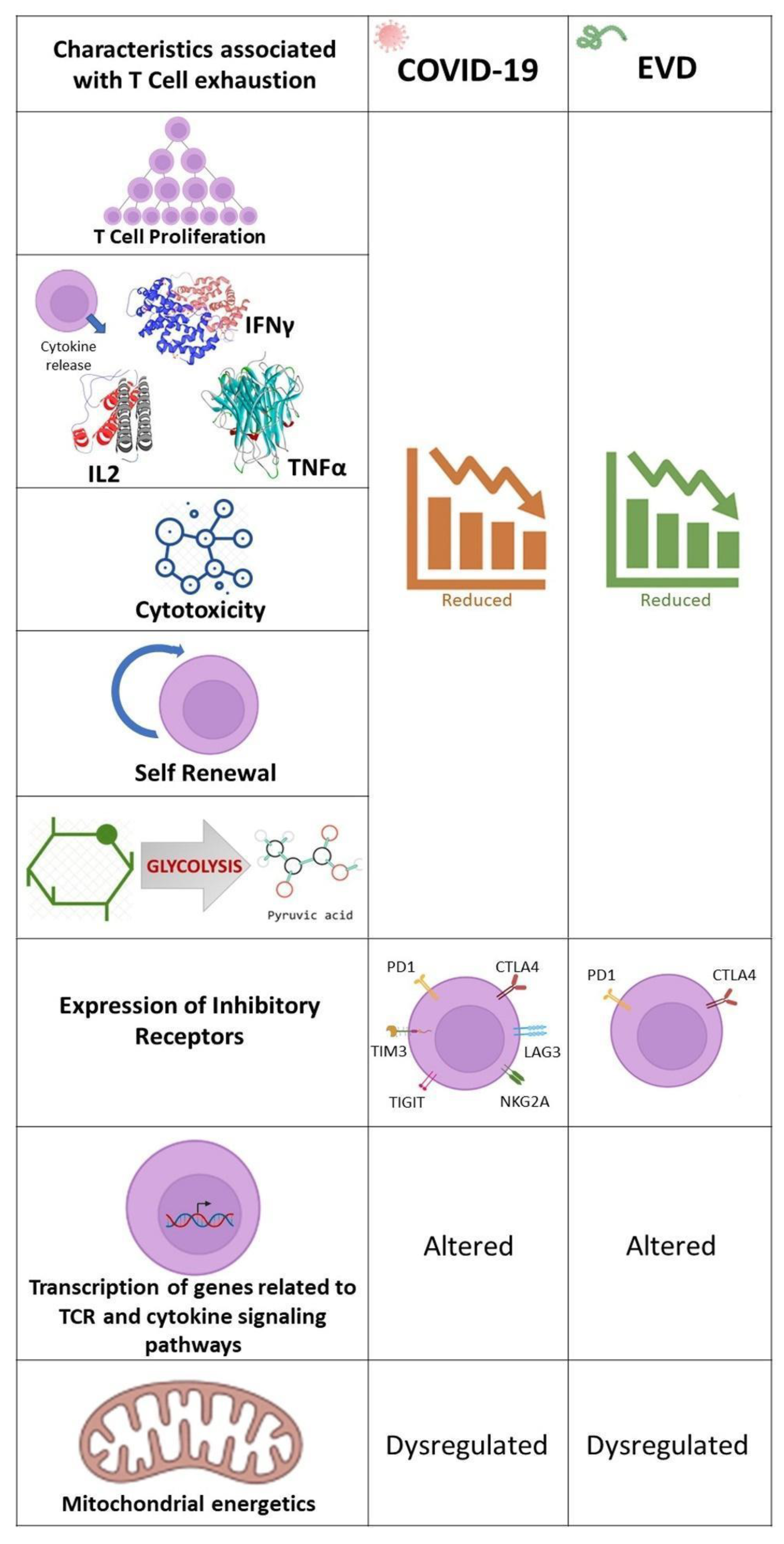

- Tolerance and Exhaustion: Defining Mechanisms of T cell Dysfunction—Science Direct. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1471490613001543?via%3Dihub (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Frontiers | Reduction and Functional Exhaustion of T Cells in Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) | Immunology. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2020.00827/full (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Kusnadi, A.; Ramírez-Suástegui, C.; Fajardo, V.; Chee, S.J.; Meckiff, B.J.; Simon, H.; Pelosi, E.; Seumois, G.; Ay, F.; Vijayanand, P.; et al. Severely ill patients with COVID-19 display impaired exhaustion features in SARS-CoV-2–reactive CD8 + T cells. Sci. Immunol. 2021, 6. Available online: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciimmunol.abe4782 (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Agrati, C.; Castilletti, C.; Casetti, R.; Sacchi, A.; Falasca, L.; Turchi, F.; Tumino, N.; Bordoni, V.; Cimini, E.; Viola, D.; et al. Longitudinal characterization of dysfunctional T cell-activation during human acute Ebola infection. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2164.

- Frontiers | T-Cell Exhaustion in Chronic Infections: Reversing the State of Exhaustion and Reinvigorating Optimal Protective Immune Responses | Immunology. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2018.02569/full (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Ruibal, P.; Oestereich, L.; Lüdtke, A.; Becker-Ziaja, B.; Wozniak, D.M.; Kerber, R.; Korva, M.; Cabeza-Cabrerizo, M.; Bore, J.A.; Koundouno, F.R.; et al. Unique human immune signature of Ebola virus disease in Guinea. Nature 2016, 533, 100–104.

- SARS-CoV-2 Infection: The role of PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 Axis—ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0024320521001090?via%3Dihub (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Yaqinuddin, A.; Kashir, J. Innate immunity in COVID-19 patients mediated by NKG2A receptors, and potential treatment using Monalizumab, Cholroquine, and antiviral agents. Med. Hypotheses 2020, 140, 109777.

- Modabber, Z.; Shahbazi, M.; Akbari, R.; Bagherzadeh, M.; Firouzjahi, A.; Mohammadnia-Afrouzi, M. TIM-3 as a potential exhaustion marker in CD4 + T cells of COVID-19 patients. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2021, 9, 1707–1715.

- Distinctive Features of SARS-CoV-2-Specific T Cells Predict Recovery from Severe COVID-19—ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211124721008275?via%3Dihub (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Frontiers | Analysis of Co-Inhibitory Receptor Expression in COVID-19 Infection Compared to Acute Plasmodium Falciparum Malaria: LAG-3 and TIM-3 Correlate with T Cell Activation and Course of Disease | Immunology. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2020.01870/full (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Deen, G.F.; Broutet, N.; Xu, W.; Knust, B.; Sesay, F.R.; McDonald, S.L.; Ervin, E.; Marrinan, J.E.; Gaillard, P.; Habib, N.; et al. Ebola RNA Persistence in Semen of Ebola Virus Disease Survivors—Final Report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1428–1437.

- Rodriguez, L.L.; De Roo, A.; Guimard, Y.; Trappier, S.G.; Sanchez, A.; Bressler, D.; Williams, A.J.; Rowe, A.K.; Bertolli, J.; Khan, A.S.; et al. Persistence and Genetic Stability of Ebola Virus during the Outbreak in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1995. J. Infect. Dis. 1999, 179, S170–S176.

- Varkey, J.B.; Shantha, J.G.; Crozier, I.; Kraft, C.S.; Lyon, G.M.; Mehta, A.K.; Kumar, G.; Smith, J.R.; Kainulainen, M.H.; Whitmer, S.; et al. Persistence of Ebola Virus in Ocular Fluid during Convalescence. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2423–2427.

- Howlett, P.; Brown, C.; Helderman, T.; Brooks, T.; Lisk, D.; Deen, G.; Solbrig, M.; Lado, M. Ebola Virus Disease Complicated by Late-Onset Encephalitis and Polyarthritis, Sierra Leone. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016, 22, 150–152.

- Assessment of the Risk of Ebola Virus Transmission from Bodily Fluids and Fomites | The Journal of Infectious Diseases | Oxford Academic. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/jid/article/196/Supplement_2/S142/858852 (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- A review on human body fluids for the diagnosis of viral infections: Scope for rapid detection of COVID-19: Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics: Vol 21, No 1. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14737159.2021.1874355?journalCode=iero20 (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Kutti-Sridharan, G.; Vegunta, R.; Vegunta, R.; Mohan, B.P.; Rokkam, V.R.P. SARS-CoV2 in Different Body Fluids, Risks of Transmission, and Preventing COVID-19: A Comprehensive Evidence-Based Review. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 11, 97.

- Keita, A.K.; Koundouno, F.R.; Faye, M.; Düx, A.; Hinzmann, J.; Diallo, H.; Ayouba, A.; Le Marcis, F.; Soropogui, B.; Ifono, K.; et al. Resurgence of Ebola virus in 2021 in Guinea suggests a new paradigm for outbreaks. Nature 2021, 597, 539–543.

- Christie, A.; Davies-Wayne, G.J.; Cordier-Lasalle, T.; Blackley, D.J.; Laney, A.S.; Williams, D.E.; Shinde, S.A.; Badio, M.; Lo, T.; Mate, S.E.; et al. Possible Sexual Transmission of Ebola Virus—Liberia, 2015. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2015, 64, 479–481.

- Mate, S.E.; Kugelman, J.R.; Nyenswah, T.G.; Ladner, J.T.; Wiley, M.R.; Cordier-Lassalle, T.; Christie, A.; Schroth, G.P.; Gross, S.M.; Davies-Wayne, G.J.; et al. Molecular Evidence of Sexual Transmission of Ebola Virus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2448–2454.

- Diallo, B.; Sissoko, D.; Loman, N.; Bah, H.A.; Bah, H.; Worrell, M.C.; Conde, L.S.; Sacko, R.; Mesfin, S.; Loua, A.; et al. Resurgence of Ebola Virus Disease in Guinea Linked to a Survivor with Virus Persistence in Seminal Fluid for More Than 500 Days. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 63, 1353–1356.

- Townsend, J.P.; Hassler, H.B.; Wang, Z.; Miura, S.; Singh, J.; Kumar, S.; Ruddle, N.H.; Galvani, A.P.; Dornburg, A. The durability of immunity against reinfection by SARS-CoV-2: A comparative evolutionary study. Lancet Microbe 2021, 2, e666–e675.

- IQureshi, A.I.; Baskett, W.I.; Huang, W.; Lobanova, I.; Naqvi, S.H.; Shyu, C.-R. Reinfection with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in Patients Undergoing Serial Laboratory Testing. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 74, 294–300.

- Mallapaty, S. COVID reinfections surge during Omicron onslaught. Nature 2022.

- Recurrence and Reinfection—A New Paradigm for the Management of Ebola Virus Disease—ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1201971215002921#bib0310 (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Gupta, M.; Mahanty, S.; Greer, P.; Towner, J.S.; Shieh, W.-J.; Zaki, S.R.; Ahmed, R.; Rollin, P.E. Persistent Infection with Ebola Virus under Conditions of Partial Immunity. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 958–967.

- Qiu, X.; Audet, J.; Wong, G.; Fernando, L.; Bello, A.; Pillet, S.; Alimonti, J.B.; Kobinger, G.P. Sustained protection against Ebola virus infection following treatment of infected nonhuman primates with ZMAb. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 3365.

- Kaech, S.M.; Ahmed, R. Memory CD8+ T cell differentiation: Initial antigen encounter triggers a developmental program in naïve cells. Nat. Immunol. 2001, 2, 415–422.

- Tipton, T.R.W.; Hall, Y.; Bore, J.A.; White, A.; Sibley, L.S.; Sarfas, C.; Yuki, Y.; Martin, M.; Longet, S.; Mellors, J.; et al. Characterisation of the T-cell response to Ebola virus glycoprotein amongst survivors of the 2013–16 West Africa epidemic. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1153.

- SARS-CoV-2-Specific T Cell Memory is Sustained in COVID-19 Convalescent Patients for 10 Months with Successful Development of Stem Cell-Like Memory T Cells | Nature Communications. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-24377-1 (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Eggenhuizen, P.J.; Ng, B.H.; Chang, J.; Cheong, R.M.; Yellapragada, A.; Wong, W.Y.; Ting, Y.T.; Monk, J.A.; Gan, P.-Y.; Holdsworth, S.R.; et al. Heterologous Immunity Between SARS-CoV-2 and Pathogenic Bacteria. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 821595.

- Kundu, R.; Narean, J.S.; Wang, L.; Fenn, J.; Pillay, T.; Fernandez, N.D.; Conibear, E.; Koycheva, A.; Davies, M.; Tolosa-Wright, M.; et al. Cross-reactive memory T cells associate with protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection in COVID-19 contacts. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 80.

- Gattinoni, L.; Speiser, D.E.; Lichterfeld, M.; Bonini, C. T memory stem cells in health and disease. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 18–27.

- Longitudinal Antibody and T Cell Responses in Ebola Virus Disease Survivors and Contacts: An Observational Cohort Study—ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1473309920307362?via%3Dihub (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Wendo, C. Caring for the survivors of Uganda’s Ebola epidemic one year on. Lancet 2001, 358, 1350.

- Scott, J.T.; Sesay, F.R.; Massaquoi, T.A.; Idriss, B.R.; Sahr, F.; Semple, M.G. Post-Ebola Syndrome, Sierra Leone. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016, 22, 641–646.

- Nalbandian, A.; Sehgal, K.; Gupta, A.; Madhavan, M.V.; McGroder, C.; Stevens, J.S.; Cook, J.R.; Nordvig, A.S.; Shalev, D.; Sehrawat, T.S.; et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 601–615.

- Fausther-Bovendo, H.; Qiu, X.; McCorrister, S.; Westmacott, G.; Sandstrom, P.; Castilletti, C.; Di Caro, A.; Ippolito, G.; Kobinger, G.P. Ebola virus infection induces autoimmunity against dsDNA and HSP60. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, srep42147.

- Rojas, M.; Rodríguez, Y.; Acosta-Ampudia, Y.; Monsalve, D.M.; Zhu, C.; Li, Q.-Z.; Ramírez-Santana, C.; Anaya, J.-M. Autoimmunity is a hallmark of post-COVID syndrome. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 129.

- Chang, S.E.; Feng, A.; Meng, W.; Apostolidis, S.A.; Mack, E.; Artandi, M.; Barman, L.; Bennett, K.; Chakraborty, S.; Chang, I.; et al. New-onset IgG autoantibodies in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5417.

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506.

- Gazzaz, Z.J. Diabetes and COVID-19. Open Life Sci. 2021, 16, 297–302.

- Simpson-Yap, S.; De Brouwer, E.; Kalincik, T.; Rijke, N.; Hillert, J.A.; Walton, C.; Edan, G.; Moreau, Y.; Spelman, T.; Geys, L.; et al. Associations of Disease-Modifying Therapies With COVID-19 Severity in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurology 2021, 97, e1870–e1885.

- Frontiers | Effect of Different Disease-Modifying Therapies on Humoral Response to BNT162b2 Vaccine in Sardinian Multiple Sclerosis Patients | Immunology. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2021.781843/full (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Brodin, P. Immune determinants of COVID-19 disease presentation and severity. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 28–33.

- Francesconi, P.; Yoti, Z.; Declich, S.; Onek, P.A.; Fabiani, M.; Olango, J.; Andraghetti, R.; Rollin, P.; Opira, C.; Greco, D.; et al. Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever Transmission and Risk Factors of Contacts, Uganda. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2003, 9, 1430–1437.

- Dietz, P.M.; Jambai, A.; Paweska, J.T.; Yoti, Z.; Ksaizek, T.G. Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Ebola Virus Disease in Sierra Leone—23 May 2014 to 31 January 2015. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 61, 1648–1654.

- Rogers, K.J.; Shtanko, O.; Vijay, R.; Mallinger, L.N.; Joyner, C.J.; Galinski, M.R.; Butler, N.S.; Maury, W. Acute Plasmodium Infection Promotes Interferon-Gamma-Dependent Resistance to Ebola Virus Infection. Cell Rep. 2020, 30, 4041–4051.e4.

- Edwards, H.M.; Counihan, H.; Bonnington, C.; Achan, J.; Hamade, P.; Tibenderana, J.K. The impact of malaria coinfection on Ebola virus disease outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251101.

- Rosenke, K.; Mercado-Hernandez, R.; Cronin, J.; Conteh, S.; Duffy, P.; Feldmann, H.; De Wit, E. The Effect of Plasmodium on the Outcome of Ebola Virus Infection in a Mouse Model. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 218, S434–S437.