Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Sirius Huang and Version 1 by Yolanda Olmos.

The endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) machinery is an evolutionarily conserved membrane remodeling complex that is used by the cell to perform reverse membrane scission in essential processes like protein degradation, cell division, and release of enveloped retroviruses. ESCRT-III, together with the AAA ATPase VPS4, harbors the main remodeling and scission function of the ESCRT machinery, whereas early-acting ESCRTs mainly contribute to protein sorting and ESCRT-III recruitment through association with upstream targeting factors.

- ESCRT

- membrane scission

- reverse topology

1. Introduction

Eukaryotic cellular membranes are highly dynamic entities that undergo continuous remodeling, fusion, budding, and fission events that are essential to cell and tissue viability. The endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) machinery has been identified as a key player in an increasing number of these membrane-remodeling events. ESCRTs have the unique ability to catalyze membrane fission from within membrane necks, in opposition to the well-characterized formation of coated vesicles, where fission occurs from the vesicle neck exterior [1]. This ‘reverse’-topology membrane scission constitutes the primary biochemical function of ESCRTs and allows the constriction and scission of membrane necks and the repair of membrane fenestrations; for example, when the plasma membrane is punctured or damaged. Over the past recent years, a myriad of cellular functions for the ESCRT machinery have been described. Functions range from the formation of multivesicular bodies (MVBs) in the endosomal sorting pathway [2], virus budding [3], and cytokinetic abscission [4], to nuclear envelope surveillance and reformation [5,6[5][6][7],7], autophagosome closure [8], and plasma-membrane [9] and lysosome membrane repair [10,11][10][11]. ESCRT biology and functions are described in detail in comprehensive reviews [12,13,14,15][12][13][14][15].

2. Membrane Remodeling by ESCRTs

Found in Archaea [16[16][17][18],17,18], ESCRTs are highly conserved through evolution. Here the main focus is on mammalian cells and yeast, where the ESCRT machinery comprises four multimeric protein core complexes termed ESCRT-0, ESCRT-I, ESCRT-II, and ESCRT-III, plus the AAA ATPase VPS4 and additional accessory proteins (Table 1). Bacteria and Archaea express ESCRT-III proteins but lack ESCRT-0, -I, and -II components [19,20][19][20]; HRS and STAM (ESCRT-0) are not found in plants, but ESCRT-I to -III are conserved [21,22,23][21][22][23].

Table 1.

ESCRT complexes and their protein subunits in yeast and humans.

| Complex | S. cerevisiae | H. sapiens |

|---|---|---|

| ESCRT-0 | Vps27 | HGS (HRS) |

| Hse1 | STAM1, STAM2 | |

| ESCRT-I | Vps23 (Stp22) | TSG101 |

| Vps28 | VPS28 | |

| Vps37 (Srn2) | VPS37A/B/C/D | |

| Mvb12 | MVB12A/B, UBAP1, UBA1L, UMAD1 | |

| ESCRT-II | Vps22 (Snf8) | EAP30 (SNF8) |

| Vps25 | EAP20 (VPS25) | |

| Vps36 | EAP45 (VPS36) | |

| ESCRT-III | Did2 (Vps46, Chm1) | CHMP1A/B |

| Did4 (Vps2, Chm2) | CHMP2A/B | |

| Vps24 (did3) | CHMP3 | |

| Snf7 (Vps32, Did1) | CHMP4A/B/C | |

| Vps60 (Chm5) | CHMP5 | |

| Vps20 (Chm6) | CHMP6 | |

| Chm7 | CHMP7 | |

| Ist1 | IST1 | |

| ESCRT-associated | Vps4 | VPS4A/B (SKD1) |

| Vta1 | VTA1 (LIP5, DRG-1) | |

| Bro1 (Vps31) | ALIX (PDCD6IP), HD-PTP (PTPN23) | |

| Doa4 | UBPY, STAMBP |

Alternative protein symbols are shown in parentheses.

Most ESCRT-mediated functions require a topologically equivalent reverse membrane remodeling for their completion. In addition, ESCRTs can carry out normal topology scission, from the outside of membrane necks [24,25,26][24][25][26]. ESCRTs constitute, therefore, a highly versatile remodeling machinery, and their mechanism of action has attracted a great deal of research efforts over the past years.

Normally localized in the cytoplasm, ESCRT subunits are sequentially recruited by site-specific adaptor proteins to different membranes. For instance, ESCRT-0 is essential for consecutive recruitment of other ESCRT components to the endosomal membrane in multivesicular body biogenesis [27,28][27][28]; CEP55, SEPT9, and additional pathways recruit ESCRT-I to intercellular bridges to facilitate cytokinetic abscission [4,29,30,31][4][29][30][31]; and viral Gag proteins recruit ESCRT-I in retroviral egression from the plasma membrane [32,33][32][33]. Recruited early-acting ESCRT factors initiate membrane bending and nucleate the assembly of the downstream ESCRT-III components. ESCRT-III forms a membrane-interacting oligomeric filament that is thought to mediate the membrane remodeling event, eventually resulting in scission [1,34][1][34]. Not all ESCRT-mediated biological processes require all complexes, but ESCRT-III and VPS4 appear to be universally required.

2.1. ESCRT-III Structure and Assembly

There are eight ESCRT-III proteins in yeast, and twelve in humans, named charged multivesicular body proteins (CHMPs) (Table 1). CHMP4/Snf7, CHMP3/Vps24, and CHMP2/Vps2, together with VPS4/Vps4, were shown to be indispensable components of the filaments that mediate membrane remodeling [35,36,37,38][35][36][37][38]. CHMP7 performs specialized functions in nuclear envelope reformation and repair [39], whereas CHMP5 remains poorly characterized. Structural work revealed that all CHMP proteins share a core structure that is thought to adopt two different conformations, known as open or closed [40]. In their closed state, they form a four-helix bundle, with α1 and α2 helices forming a long hairpin, the shorter helices α3 and α4 packed against the hairpin, and helix 5 folding back and packing against the closed end of the helical hairpin, as shown by the crystal structures of CHMP3 [41,42][41][42] and IST1 [43,44][43][44]. In their open state, helices α2 and α3 merge, disrupting the interaction between helix α4 and the hairpin, as shown for CHMP1B [43,44][43][44] and truncated forms of CHMP4 [45,46][45][46]. An intermediate, semi-open conformation, has also been described for yeast Vps24 [47]. Importantly, ESCRT-III proteins in all three conformations seem to be able to assemble into filaments [40,43,44,47][40][43][44][47]. However, these filaments might show different abilities in membrane binding and flexibility [40]. Whereas the closed conformation does not display membrane binding interfaces [41,48,49][41][48][49] and is thought to result in more rigid filaments, the more extended open conformation displays extended membrane-binding interfaces, appears to be in the polymerization-competent state [12,41[12][41][50],50], and forms highly flexible filaments [46[46][51],51], which would potentially allow the binding to membranes of a wide range of curvatures.

In general, ESCRT-III polymers are curved and flexible, and most possess a membrane-binding interface [40]. They often form copolymers with other ESCRT-III subunits and can take a variety of shapes on membranes in vitro and in vivo, including rings, spirals, helices, and cones [14,44,52,53][14][44][52][53]. These morphologies have been well characterized in recent years through structural biology approaches, cryo-electron microscopy, and atomic-force microscopy [43,45,46][43][45][46]. Interestingly, recent data have shown that the ESCRT-I complex can also form helical filaments [54], suggesting that early -acting ESCRT factors might not merely be bridging adaptors, but can also be involved in membrane deformation and ESCRT polymerization.

2.2. The Role of VPS4

ESCRT-III-mediated processes crucially rely on the activity of the AAA ATPase VPS4, the only known ATP-consuming factor in the membrane-scission reaction mediated by ESCRT [36]. VPS4 is recruited to membranes in order to translocate and unfold ESCRT-III components [55]; this process is mediated through the binding of microtubule interacting and trafficking (MIT) domains to MIT-interacting motifs (MIMs) in ESCRT-III proteins [56,57][56][57]. VPS4 function is essential to recycle ESCRT-III filaments and ensure high cytosolic levels of ESCRT-III monomers. Importantly, it also allows the remodeling of the ESCRT-III filament during pre-scission stages ([58,59][58][59] and Section 2.3 Section 2.3 below) and increasing evidence suggests that VPS4 can additionally play a more active and mechanical role in membrane constriction and scission [14,34,60][14][34][60].

2.3. Mechanism of ESCRT-III Membrane Remodeling

In the last few years, a great deal of research work has been performed in order to understand how membrane constriction and scission is mediated by the ESCRT-III machinery (reviewed in [40,61,62][40][61][62]). Important advances in the field were achieved by using in vitro reconstitution studies using purified ESCRT subunits [44,47,59,63,64,65][44][47][59][63][64][65]. These allowed investigation of the structures, molecular properties, and interplay of various ESCRT-III filaments. Models for ESCRT-III-mediated membrane scission have been divided into three main categories [1,62][1][62]: in the classic ‘dome’ models ESCRT-III polymerizes forming a spiraling membrane-bound filament with consecutively narrower rings, and opposing membranes are brought together by fusion on top of a constricted cone or dome, with the narrow end of the cone either pointing towards the vesicle or towards the cytoplasm [66,67][66][67]; in the ‘buckling/unbuckling’ models mechanical forces provided by tension-driven transitions between planar and helical ESCRT-III filament configurations allow tubule extrusion [52] or vesicle release [34]; finally, in the ‘protomer conversion’ models, filament constriction occurs in response to Vps4-mediated subunit turnover [53] or incorporation into the filament of additional ESCRT-III subunits with different properties [44]; this can change filament’s curvature and rigidity, leading to a rapid structural change and subsequent membrane neck constriction. The proposed models are not mutually exclusive and, in fact, recent studies have culminated in a unifying model that combines all these mechanisms to explain constriction and scission of membrane necks by ESCRTs [59].

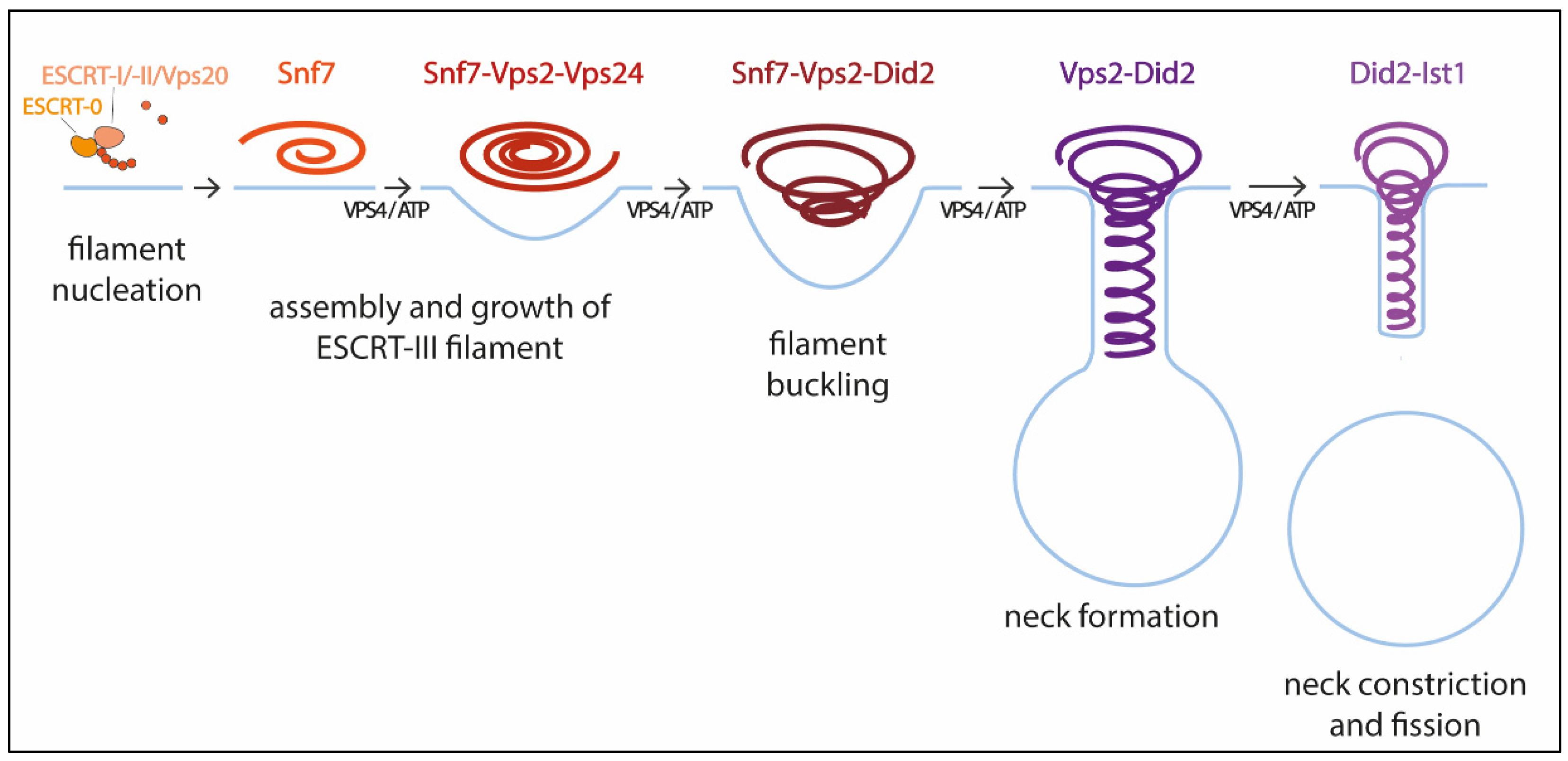

Pfitzner et al. reconstituted ESCRT-III-Vps4 assembly on supported bilayers, liposomes, and within membrane tubules, and analyzed ESCRT-III subunit binding and release, membrane deformation, changes in ESCRT-III filament orientation, and ESCRT-induced membrane fission [59]. As a result, they proposed a mechanism of stepwise changes in ESCRT-III filament structure and mechanical properties via exchange of the filament subunits to catalyze ESCRT-III activity (Figure 1). In this model, the upstream ESCRT machinery nucleates Snf7, which polymerizes forming a single-stranded filament. This filament is thought to form first because it binds well to flat membranes and can be nucleated by early-acting ESCRT complexes in vivo [54,59,63][54][59][63]. The Snf7 filament then recruits a second filament containing the Vps2-Vps24 pair, which together recruit a third filament comprising Vps2 and Did2; Vps2-Did2 in turn recruits and is finally replaced by the Did2-Ist1 pair. The different biophysical properties of each ESCRT-III subunit results in heteropolymers that differ in their assembly, disassembly, recruiting, and membrane deformation properties. Vps2-Vps4 filaments have higher affinity for Snf7 filaments, whereas Vps2-Did2 filaments bind best when Snf7 and Vps2–Vps24 filaments are already present, explaining the recruitment order. Conversely, Vps2–Did2 filaments recruit Vps4 depolymerization activity better, which favors ESCRT-III disassembly. As mentioned above, Vps4 binds most ESCRT-III subunits and mediates their extraction and exchange, which is necessary for successful narrowing of the neck [36,60][36][60]. Moreover, Vps4 disassembles ESCRT-III filaments with different efficiencies, in the order Vps2-Vps24 > Snf7 > Vps2-Did2 > Did2-Ist1. This results in a unidirectional reaction pathway (Figure 1). Interestingly, the different filaments also show distinct membrane deformation activities. The exchange of Vps24 for Did2 bends the polymer-membrane interface, triggering the transition from flat spiral polymers to helical filaments and driving the formation of membrane protrusions. This ends with the formation of a tight Did2-Ist1 helix that constricts the tubule and is shown to be able to promote fission when bound on the inside of membrane necks. Vps4 activity is required not only for constriction but also to complete scission, probably playing a role in fission beyond the establishment of the Did2/Ist1 polymer.

Figure 1. Model for membrane constriction and fission driven by ESCRT-III filament assembly and disassembly. The figure illustrates the sequential recruitment of ESCRT-III components, polymerization, and replacement of different filament subunits driven by Vps4, resulting in constriction and final scission of the membrane (adapted from [59]).

With this model Pfitzner et al. established the common principles of a general mechanism by which ESCRT-III remodels membranes: a sequence of subunit exchanges that switches the architecture and mechanical properties of ESCRT-III filaments. The ESCRT field seems now to be converging on this consensus mechanistic model. Additional recent work has provided for the first time direct evidence of spontaneous Snf7 spiral buckling using HS-AFM approaches [68]. However, further investigations will be necessary to answer some of the key questions that still remain open. For instance, cryo-EM of scission-capable complexes in the reverse topology process is needed to fully understand the ESCRT mechanism. It is also essential to clarify how the same complex (Did-Ist1) can induce fission in different orientations, assembling around or inside membrane necks [24,43][24][43]. Studies using high spatial resolution to address the directionality of filament growth will also be of interest. It is also worth considering that, like in dynamin-mediated membrane fission [69], additional external forces, including cargo crowding, might also be required to finalize the progression from highly constricted membrane structures towards fission.

References

- Schöneberg, J.; Lee, I.-H.; Iwasa, J.H.; Hurley, J.H. Reverse-Topology Membrane Scission by the ESCRT Proteins. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 5–17.

- Katzmann, D.J.; Babst, M.; Emr, S.D. Ubiquitin-Dependent Sorting into the Multivesicular Body Pathway Requires the Function of a Conserved Endosomal Protein Sorting Complex, ESCRT-I. Cell 2001, 106, 145–155.

- Sundquist, W.I.; Kräusslich, H.-G. HIV-1 Assembly, Budding, and Maturation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a006924.

- Carlton, J.G.; Martin-Serrano, J. Parallels Between Cytokinesis and Retroviral Budding: A Role for the ESCRT Machinery. Science 2007, 316, 1908–1912.

- Webster, B.M.; Colombi, P.; Jäger, J.; Lusk, C.P. Surveillance of Nuclear Pore Complex Assembly by ESCRT-III/Vps4. Cell 2014, 159, 388–401.

- Olmos, Y.; Hodgson, L.; Mantell, J.; Verkade, P.; Carlton, J.G. ESCRT-III Controls Nuclear Envelope Reformation. Nature 2015, 522, 236–239.

- Vietri, M.; Schink, K.O.; Campsteijn, C.; Wegner, C.S.; Schultz, S.W.; Christ, L.; Thoresen, S.B.; Brech, A.; Raiborg, C.; Stenmark, H. Spastin and ESCRT-III Coordinate Mitotic Spindle Disassembly and Nuclear Envelope Sealing. Nature 2015, 522, 231–235.

- Takahashi, Y.; He, H.; Tang, Z.; Hattori, T.; Liu, Y.; Young, M.M.; Serfass, J.M.; Chen, L.; Gebru, M.; Chen, C.; et al. An Autophagy Assay Reveals the ESCRT-III Component CHMP2A as a Regulator of Phagophore Closure. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2855.

- Jimenez, A.J.; Maiuri, P.; Lafaurie-Janvore, J.; Divoux, S.; Piel, M.; Perez, F. ESCRT Machinery Is Required for Plasma Membrane Repair. Science 2014, 343, 1247136.

- Skowyra, M.L.; Schlesinger, P.H.; Naismith, T.V.; Hanson, P.I. Triggered Recruitment of ESCRT Machinery Promotes Endolysosomal Repair. Science 2018, 360, eaar5078.

- Radulovic, M.; Schink, K.O.; Wenzel, E.M.; Nähse, V.; Bongiovanni, A.; Lafont, F.; Stenmark, H. ESCRT-Mediated Lysosome Repair Precedes Lysophagy and Promotes Cell Survival. EMBO J. 2018, 37, e99753.

- Hurley, J.H. ESCRTs Are Everywhere. EMBO J. 2015, 34, 2398–2407.

- Vietri, M.; Radulovic, M.; Stenmark, H. The Many Functions of ESCRTs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 25–42.

- McCullough, J.; Frost, A.; Sundquist, W.I. Structures, Functions, and Dynamics of ESCRT-III/Vps4 Membrane Remodeling and Fission Complexes. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 34, 85–109.

- Migliano, S.M.; Wenzel, E.M.; Stenmark, H. Biophysical and Molecular Mechanisms of ESCRT Functions, and Their Implications for Disease. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2022, 75, 102062.

- Samson, R.Y.; Obita, T.; Freund, S.M.; Williams, R.L.; Bell, S.D. A Role for the ESCRT System in Cell Division in Archaea. Science 2008, 322, 1710–1713.

- Tarrason Risa, G.; Hurtig, F.; Bray, S.; Hafner, A.E.; Harker-Kirschneck, L.; Faull, P.; Davis, C.; Papatziamou, D.; Mutavchiev, D.R.; Fan, C.; et al. The Proteasome Controls ESCRT-III–Mediated Cell Division in an Archaeon. Science 2020, 369, eaaz2532.

- Hatano, T.; Palani, S.; Papatziamou, D.; Salzer, R.; Souza, D.P.; Tamarit, D.; Makwana, M.; Potter, A.; Haig, A.; Xu, W.; et al. Asgard Archaea Shed Light on the Evolutionary Origins of the Eukaryotic Ubiquitin-ESCRT Machinery. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3398.

- Liu, J.; Tassinari, M.; Souza, D.P.; Naskar, S.; Noel, J.K.; Bohuszewicz, O.; Buck, M.; Williams, T.A.; Baum, B.; Low, H.H. Bacterial Vipp1 and PspA Are Members of the Ancient ESCRT-III Membrane-Remodeling Superfamily. Cell 2021, 184, 3660–3673.e18.

- Junglas, B.; Huber, S.T.; Heidler, T.; Schlösser, L.; Mann, D.; Hennig, R.; Clarke, M.; Hellmann, N.; Schneider, D.; Sachse, C. PspA Adopts an ESCRT-III-like Fold and Remodels Bacterial Membranes. Cell 2021, 184, 3674–3688.e18.

- Mosesso, N.; Nagel, M.-K.; Isono, E. Ubiquitin Recognition in Endocytic Trafficking–with or without ESCRT-0. Journal of Cell Science 2019, 132, jcs232868.

- Gao, C.; Luo, M.; Zhao, Q.; Yang, R.; Cui, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Xia, J.; Jiang, L. A Unique Plant ESCRT Component, FREE1, Regulates Multivesicular Body Protein Sorting and Plant Growth. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, 2556–2563.

- González Solís, A.; Berryman, E.; Otegui, M.S. Plant Endosomes as Protein Sorting Hubs. FEBS Lett. 2022; accepted.

- Allison, R.; Lumb, J.H.; Fassier, C.; Connell, J.W.; Ten Martin, D.; Seaman, M.N.J.; Hazan, J.; Reid, E. An ESCRT–Spastin Interaction Promotes Fission of Recycling Tubules from the Endosome. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 202, 527–543.

- Chang, C.-L.; Weigel, A.V.; Ioannou, M.S.; Pasolli, H.A.; Xu, C.S.; Peale, D.R.; Shtengel, G.; Freeman, M.; Hess, H.F.; Blackstone, C.; et al. Spastin Tethers Lipid Droplets to Peroxisomes and Directs Fatty Acid Trafficking through ESCRT-III. J. Cell Biol. 2019, 218, 2583–2599.

- Mast, F.D.; Herricks, T.; Strehler, K.M.; Miller, L.R.; Saleem, R.A.; Rachubinski, R.A.; Aitchison, J.D. ESCRT-III Is Required for Scissioning New Peroxisomes from the Endoplasmic Reticulum. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 2087–2102.

- Raiborg, C.; Bache, K.G.; Gillooly, D.J.; Madshus, I.H.; Stang, E.; Stenmark, H. Hrs Sorts Ubiquitinated Proteins into Clathrin-Coated Microdomains of Early Endosomes. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002, 4, 394–398.

- Banjade, S.; Zhu, L.; Jorgensen, J.R.; Suzuki, S.W.; Emr, S.D. Recruitment and Organization of ESCRT-0 and Ubiquitinated Cargo via Condensation. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabm5149.

- Karasmanis, E.P.; Hwang, D.; Nakos, K.; Bowen, J.R.; Angelis, D.; Spiliotis, E.T. A Septin Double Ring Controls the Spatiotemporal Organization of the ESCRT Machinery in Cytokinetic Abscission. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, 2174–2182.e7.

- Merigliano, C.; Burla, R.; La Torre, M.; Del Giudice, S.; Teo, H.; Liew, C.W.; Chojnowski, A.; Goh, W.I.; Olmos, Y.; Maccaroni, K.; et al. AKTIP Interacts with ESCRT I and Is Needed for the Recruitment of ESCRT III Subunits to the Midbody. PLoS Genet. 2021, 17, e1009757.

- Addi, C.; Presle, A.; Frémont, S.; Cuvelier, F.; Rocancourt, M.; Milin, F.; Schmutz, S.; Chamot-Rooke, J.; Douché, T.; Duchateau, M.; et al. The Flemmingsome Reveals an ESCRT-to-Membrane Coupling via ALIX/Syntenin/Syndecan-4 Required for Completion of Cytokinesis. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1941.

- Martin-Serrano, J.; Zang, T.; Bieniasz, P.D. HIV-1 and Ebola Virus Encode Small Peptide Motifs That Recruit Tsg101 to Sites of Particle Assembly to Facilitate Egress. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 1313–1319.

- Meusser, B.; Purfuerst, B.; Luft, F.C. HIV-1 Gag Release from Yeast Reveals ESCRT Interaction with the Gag N-Terminal Protein Region. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 17950–17972.

- Schöneberg, J.; Pavlin, M.R.; Yan, S.; Righini, M.; Lee, I.-H.; Carlson, L.-A.; Bahrami, A.H.; Goldman, D.H.; Ren, X.; Hummer, G.; et al. ATP-Dependent Force Generation and Membrane Scission by ESCRT-III and Vps4. Science 2018, 362, 1423–1428.

- Teis, D.; Saksena, S.; Emr, S.D. Ordered Assembly of the ESCRT-III Complex on Endosomes Is Required to Sequester Cargo during MVB Formation. Dev. Cell 2008, 15, 578–589.

- Alonso, Y.; Adell, M.; Migliano, S.M.; Teis, D. ESCRT-III and Vps4: A Dynamic Multipurpose Tool for Membrane Budding and Scission. FEBS J. 2016, 283, 3288–3302.

- Morita, E.; Sandrin, V.; McCullough, J.; Katsuyama, A.; Baci Hamilton, I.; Sundquist, W.I. ESCRT-III Protein Requirements for HIV-1 Budding. Cell Host Microbe 2011, 9, 235–242.

- Banjade, S.; Shah, Y.H.; Tang, S.; Emr, S.D. Design Principles of the ESCRT-III Vps24-Vps2 Module. eLife 2021, 10, e67709.

- Olmos, Y.; Perdrix-Rosell, A.; Carlton, J.G. Membrane Binding by CHMP7 Coordinates ESCRT-III-Dependent Nuclear Envelope Reformation. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 2635–2641.

- Pfitzner, A.-K.; Moser von Filseck, J.; Roux, A. Principles of Membrane Remodeling by Dynamic ESCRT-III Polymers. Trends Cell Biol. 2021, 31, 856–868.

- Bajorek, M.; Schubert, H.L.; McCullough, J.; Langelier, C.; Eckert, D.M.; Stubblefield, W.-M.B.; Uter, N.T.; Myszka, D.G.; Hill, C.P.; Sundquist, W.I. Structural Basis for ESCRT-III Protein Autoinhibition. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009, 16, 754–762.

- Muzioł, T.; Pineda-Molina, E.; Ravelli, R.B.; Zamborlini, A.; Usami, Y.; Göttlinger, H.; Weissenhorn, W. Structural Basis for Budding by the ESCRT-III Factor CHMP3. Dev. Cell 2006, 10, 821–830.

- McCullough, J.; Clippinger, A.K.; Talledge, N.; Skowyra, M.L.; Saunders, M.G.; Naismith, T.V.; Colf, L.A.; Afonine, P.; Arthur, C.; Sundquist, W.I.; et al. Structure and Membrane Remodeling Activity of ESCRT-III Helical Polymers. Science 2015, 350, 1548–1551.

- Nguyen, H.C.; Talledge, N.; McCullough, J.; Sharma, A.; Moss, F.R.; Iwasa, J.H.; Vershinin, M.D.; Sundquist, W.I.; Frost, A. Membrane Constriction and Thinning by Sequential ESCRT-III Polymerization. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 392–399.

- McMillan, B.J.; Tibbe, C.; Jeon, H.; Drabek, A.A.; Klein, T.; Blacklow, S.C. Electrostatic Interactions between Elongated Monomers Drive Filamentation of Drosophila Shrub, a Metazoan ESCRT-III Protein. Cell Rep. 2016, 16, 1211–1217.

- Tang, S.; Henne, W.M.; Borbat, P.P.; Buchkovich, N.J.; Freed, J.H.; Mao, Y.; Fromme, J.C.; Emr, S.D. Structural Basis for Activation, Assembly and Membrane Binding of ESCRT-III Snf7 Filaments. eLife 2015, 4, e12548.

- Huber, S.T.; Mostafavi, S.; Mortensen, S.A.; Sachse, C. Structure and Assembly of ESCRT-III Helical Vps24 Filaments. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba4897.

- Lin, Y.; Kimpler, L.A.; Naismith, T.V.; Lauer, J.M.; Hanson, P.I. Interaction of the Mammalian Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport (ESCRT) III Protein HSnf7-1 with Itself, Membranes, and the AAA+ ATPase SKD1. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 12799–12809.

- Lata, S.; Roessle, M.; Solomons, J.; Jamin, M.; Gőttlinger, H.G.; Svergun, D.I.; Weissenhorn, W. Structural Basis for Autoinhibition of ESCRT-III CHMP3. J. Mol. Biol. 2008, 378, 818–827.

- McCullough, J.; Colf, L.A.; Sundquist, W.I. Membrane Fission Reactions of the Mammalian ESCRT Pathway. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2013, 82, 663–692.

- Banjade, S.; Tang, S.; Shah, Y.H.; Emr, S.D. Electrostatic Lateral Interactions Drive ESCRT-III Heteropolymer Assembly. eLife 2019, 8, e46207.

- Chiaruttini, N.; Redondo-Morata, L.; Colom, A.; Humbert, F.; Lenz, M.; Scheuring, S.; Roux, A. Relaxation of Loaded ESCRT-III Spiral Springs Drives Membrane Deformation. Cell 2015, 163, 866–879.

- Mierzwa, B.E.; Chiaruttini, N.; Redondo-Morata, L.; Moser von Filseck, J.; König, J.; Larios, J.; Poser, I.; Müller-Reichert, T.; Scheuring, S.; Roux, A.; et al. Dynamic Subunit Turnover in ESCRT-III Assemblies Is Regulated by Vps4 to Mediate Membrane Remodelling during Cytokinesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 787–798.

- Flower, T.G.; Takahashi, Y.; Hudait, A.; Rose, K.; Tjahjono, N.; Pak, A.J.; Yokom, A.L.; Liang, X.; Wang, H.-G.; Bouamr, F.; et al. A Helical Assembly of Human ESCRT-I Scaffolds Reverse-Topology Membrane Scission. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 570–580.

- Yang, B.; Stjepanovic, G.; Shen, Q.; Martin, A.; Hurley, J.H. Vps4 Disassembles an ESCRT-III Filament by Global Unfolding and Processive Translocation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015, 22, 492–498.

- Obita, T.; Saksena, S.; Ghazi-Tabatabai, S.; Gill, D.J.; Perisic, O.; Emr, S.D.; Williams, R.L. Structural Basis for Selective Recognition of ESCRT-III by the AAA ATPase Vps4. Nature 2007, 449, 735–739.

- Stuchell-Brereton, M.D.; Skalicky, J.J.; Kieffer, C.; Karren, M.A.; Ghaffarian, S.; Sundquist, W.I. ESCRT-III Recognition by VPS4 ATPases. Nature 2007, 449, 740–744.

- Adell, M.A.Y.; Vogel, G.F.; Pakdel, M.; Müller, M.; Lindner, H.; Hess, M.W.; Teis, D. Coordinated Binding of Vps4 to ESCRT-III Drives Membrane Neck Constriction during MVB Vesicle Formation. J. Cell Biol. 2014, 205, 33–49.

- Pfitzner, A.-K.; Mercier, V.; Jiang, X.; Moser von Filseck, J.; Baum, B.; Šarić, A.; Roux, A. An ESCRT-III Polymerization Sequence Drives Membrane Deformation and Fission. Cell 2020, 182, 1140–1155.e18.

- Maity, S.; Caillat, C.; Miguet, N.; Sulbaran, G.; Effantin, G.; Schoehn, G.; Roos, W.H.; Weissenhorn, W. VPS4 Triggers Constriction and Cleavage of ESCRT-III Helical Filaments. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau7198.

- Remec Pavlin, M.; Hurley, J.H. The ESCRTs–Converging on Mechanism. J. Cell Sci. 2020, 133, jcs240333.

- McCullough, J.; Sundquist, W.I. Membrane Remodeling: ESCRT-III Filaments as Molecular Garrotes. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, R1425–R1428.

- Bertin, A.; de Franceschi, N.; de la Mora, E.; Maity, S.; Alqabandi, M.; Miguet, N.; di Cicco, A.; Roos, W.H.; Mangenot, S.; Weissenhorn, W.; et al. Human ESCRT-III Polymers Assemble on Positively Curved Membranes and Induce Helical Membrane Tube Formation. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2663.

- Alqabandi, M.; de Franceschi, N.; Maity, S.; Miguet, N.; Bally, M.; Roos, W.H.; Weissenhorn, W.; Bassereau, P.; Mangenot, S. The ESCRT-III Isoforms CHMP2A and CHMP2B Display Different Effects on Membranes upon Polymerization. BMC Biol. 2021, 19, 66.

- Moser von Filseck, J.; Barberi, L.; Talledge, N.; Johnson, I.E.; Frost, A.; Lenz, M.; Roux, A. Anisotropic ESCRT-III Architecture Governs Helical Membrane Tube Formation. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1516.

- Fabrikant, G.; Lata, S.; Riches, J.D.; Briggs, J.A.G.; Weissenhorn, W.; Kozlov, M.M. Computational Model of Membrane Fission Catalyzed by ESCRT-III. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009, 5, e1000575.

- Henne, W.M.; Buchkovich, N.J.; Emr, S.D. The ESCRT Pathway. Dev. Cell 2011, 21, 77–91.

- Jukic, N.; Perrino, A.P.; Humbert, F.; Roux, A.; Scheuring, S. Snf7 Spirals Sense and Alter Membrane Curvature. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2174.

- Roux, A.; Uyhazi, K.; Frost, A.; De Camilli, P. GTP-Dependent Twisting of Dynamin Implicates Constriction and Tension in Membrane Fission. Nature 2006, 441, 528–531.

More