Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Seng Chuan Tang and Version 2 by Nora Tang.

Super-enhancers (SEs) are clusters of neighboring enhancers spanning over 10 kb with high-fold enhancer activity that drive cell-type specific gene expression. 3D genome organization enables SEs to interact with specific gene promoters and orchestrates their activity as evidenced by the high frequency of chromatin interactions at the genomic loci containing SEs. SEs contain many TF binding sites, and are heavily loaded with enhancer-associated chromatin features, such as master TFs (e.g., Oct4, Sox2, Nanog, and Klf4 in embryonic stem cells), RNA Pol II, MED1, and chromatin modifiers (p300 and BRD4). The recruited factors alter the chromatin structure, leading to interactions with promoters and RNA Pol II, a process mediated by enhancer–promoter looping. Phase separation may facilitate the assembly and function of SEs.

- super-enhancers

- chromatin looping

- phase-separated condensates

1. Super-Enhancers and Chromatin Interactions

The human genome is organized into higher order structures, and such structures are important for transcriptional regulation [1][11]. Individual chromosomes occupy distinct regions of the nucleus, known as chromosome territories, that are themselves spatially segregated in A and B compartments. The A compartment is associated with actively transcribed genes, whereas the B compartment is associated with epigenetically silent genes and gene-poor DNA. Genome-wide Hi-C analysis showed that loci located on the same chromosome interact more frequently than any two loci located on different chromosomes [2][12]. At the sub-megabase scale, chromatin is compartmentalized into smaller structures known as topologically associating domains (TADs). TADs are self-interacting, loop-like domains that contain interacting cis-regulatory elements and target genes [3][13]. The chromatin fiber is organized into a collection of DNA loops which establish chromatin interactions with distant regions and regulate the activity of genes. This is explained by the loop extrusion model in which frequent transient loops are organised by structural maintenance of chromosomes (SMC) complexes that reel in chromatin, forming growing loops that stop at CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) boundaries [4][5][14,15]. TAD borders are demarcated by convergently oriented CTCF binding sites that obstruct loop extrusion and cohesin translocation. CTCF proteins act as loop anchors and insulate TADs from neighboring regions. Insulated neighborhoods are chromosomal loops, which bound by CTCF homodimers, occupy by the cohesin complex, and contain at least one gene [6][7][16,17]. Most of the enhancer–promoter interactions are contained within insulated neighborhoods [8][18].

Several SE-associated factors, such as the CTCF and cohesin complex mediate chromatin interactions within the SEs [8][18]. Integrated Hi-C and ChIP-seq data analysis identified enriched CTCF binding, and a higher frequency of chromatin interactions present at hub enhancers within the hierarchical SEs [9][19]. Thus, CTCFs regulate cell type-specific and cancer-specific SEs [10][20].

The transcriptional activity of SEs is restricted within insulated neighbourhoods enclosed by CTCFs and cohesin complex such that SEs are specifically tethered to their target genes. Cohesin loss leads to the development of myeloid neoplasms [11][21]. Higher occupancy of cohesin and CTCF molecules that mediate long-range chromatin interactions and chromatin looping is noted in SE constituents, suggesting the loops connecting SEs and promoters are strictly controlled [12][22]. In T-lymphoblastic leukemia, SEs targeting the IL7R locus are restricted within the same CTCF-organized neighborhood [13][23]. SEs insulated by strong TAD boundaries are frequently co-duplicated in cancer patients [14][24].

The disruption of the insulated chromatin neighborhood by deletion of the CTCF binding site at one of the borders causes dysregulation of intradomain genes and activation of genes outside the neighborhood [6][16]. Functional CTCF occupancy at the borders of the SE domain was validated in the in vivo mouse model [15][25]. In mammary tissue, mammary-specific Wap SE (comprised of three constituent enhancers) activated neighboring non-mammary gene Ramp3 separated by three CTCF sites. Although CTCF does not completely block SE activity, deletion of CTCF in mice demonstrated the capacity to muffle gene activation. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated deletion of three CTCF sites did not alter Wap expression, but increased Ramp3 expression (seven-fold) in mammary tissue from parous mice by establishing enhanced chromatin interactions between S3 of Wap SE and the first intron of Ramp3 [15][25]. This indicates that CTCF sites are porous borders instead of tight blocks and they muffle SE-mediated activation of secondary target genes present outside of the insulated neighborhood. Thus, proto-oncogenes can be activated in cancer cells upon loss of the insulated boundary through enhancers present outside the neighborhood [16][26].

In cancer models, elevated MYC oncogene levels are associated with aggressive tumors. One of the ways that this dysregulation is achieved is through the acquisition of large tumor-specific SEs present within 2.8 Mb MYC TAD. In tumor cells, SEs at the MYC locus are looped to a common CTCF site within the MYC promoter (Figure 12A) [17][27]. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated perturbation of a MYC promoter-proximal CTCF binding site in tumor cells leads to reduced chromatin interactions between the MYC promoter and distal SEs present downstream of MYC, indicating that the CTCF docking site is necessary in mediating enhancer–promoter looping [17][27]. DNA methylation of these MYC enhancer docking site with dCas9-DNMT3A-3L protein and specific gRNA reduced MYC expression in K562 and HCT-116 cancer cell lines, possibly due to abrogation of CTCF binding upon methylation [17][27].

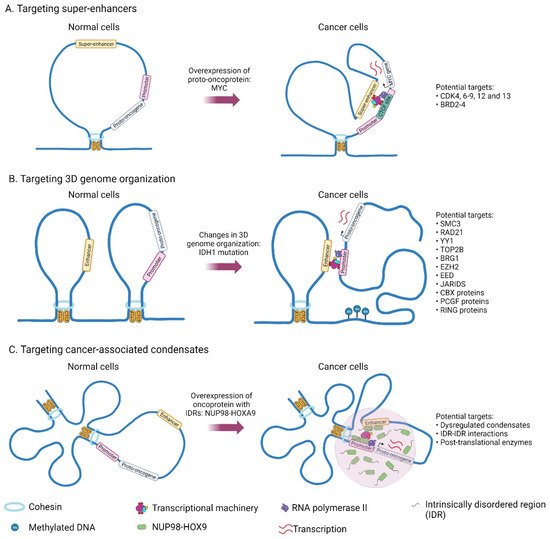

Figure 12.

Genes and structures that are deregulated in cancer and which could potentially be targeted for cancer therapy.

Recently, 3D genome organization in T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-ALL) was characterized, in which TAD fusion was observed in the MYC locus in T-ALL, subjecting its promoter to chromatin interactions with SE [18][28]. TAD fusion in the MYC locus is associated with increased inter-TAD interaction and the absence of CTCF binding. This fusion brings MYC promoter and SE into proximity establishing chromatin interactions that are separated by insulation in normal T cells. Thus CTCF-mediated insulation of TAD determines the accessibility of chromatin looping of the MYC promoter with SE. Also, an increase in CTCF binding downstream of SEs was noted, and this could act as super-anchors that mediate SEs and gene interaction [19][20][29,30].

Various dCas9 systems, such as dCas9-KRAB [21][31], dCas9-DNMT3A [21][31], dCas9-DNMT3A-3L [21][31], dC9Sun-D3A [22][32], and dCas9-MQ1 [23][33], can be used to potentially target methylation of enhancer docking sites and alter CTCF binding to these docking sites. With improvements in the delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 and CRISPR/dCas9 vectors [24][25][34,35], targeting oncogenic enhancer docking sites and super-anchors using these vectors could become potential future cancer therapies.

2. Mechanisms Related to the Acquisition of Super-Enhancers in Cancer

Cancer cells can acquire oncogenic SEs either through chromosomal rearrangements, DNA mutations and indels, 3D chromatin structural changes, or viral oncogenes [26][27][28][36,37,38]. In particular, the disruption of TAD boundaries and dysregulated chromatin interactions can activate oncogene expression. For example, mutations or insertions create a novel binding site for master TFs that recruit other factors and form a strong SE which then activates adjacent oncogenes. Deletion of the CTCF binding site leads to the activation of a silent oncogene by juxtaposed SE. The binding of activation-induced cytidine deaminase triggers genome instability and gene translocation which brings oncogenes near SEs [29][39]. SEs are exceptionally sensitive to perturbations by transcriptional drugs [30][40]. A small change in the concentration of components associated with SE activity, such as transcriptional co-activators, causes drastic changes in SE-associated gene transcription [31][41]. Thus, disruption of the SE-associated gene transcription by targeting these components seems a promising approach for anti-cancer therapy.

3. Targeting Transcriptional Co-Activators and Chromatin Remodelers

2. Targeting Transcriptional Co-Activators and Chromatin Remodelers

Co-activators such as BRDs (BRD2-4, and BRDT) and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK7, and CDK9) may be targeted to disrupt SEs. Several bromodomain and extra-terminal domain (BET) inhibitors, and CDK inhibitors have been reported to target SEs, as shown in Table 1. For example, treatment of MM1.S myeloma cells with JQ1 (BRD4 inhibitor) leads to preferential loss of BRD4 at SEs and selective inhibition of SE-driven MYC transcription [31][41]. Similar effects were seen in other cancer types such as colorectal cancer [32][42], ovarian cancer [33][43], Merkel cell carcinoma [34][44], B-cell lymphoma [35][45], and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma [36][46].

Table 1.

Targets and their potential inhibitors of disrupting SE components.

| Target | Potential Small-Molecule Inhibitors | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| CDK7 | THZ1, SY-1365, SY-5609, and THZ2 | [37][38][39][40][41][42][50,61,62,63,64,65] |

| CDK4 | Ribociclib (LEE011) | [43][44][6,66] |

| CDK6 | Ribociclib (LEE011) | [43][44][6,66] |

| CDK12 | THZ1, THZ531 | [41][45][64,67] |

| CDK13 | THZ1, THZ531 | [41][45][64,67] |

| CDK8 | Cortistatin A, SEL120-34A | [46][47][58,68] |

| CDK9 | NVP-2 | [41][64] |

| BRD2 | I-BET762, OTX015, CPI0610, and BI-89499 |

[48][49][50][69,70,71] |

| BRD3 | I-BET762, OTX015, CPI0610, and BI-89499 |

[48][49][50][69,70,71] |

| BRD4 | JQ1, I-BET151, and I-BET762, OTX015, CPI0610, and BI-89499 |

[31][48][49][50][51][41,69,70,71,72] |

CDK7 and CDK9 are important in the initiation and elongation of transcription mediated by the phosphorylation of RNA Pol II. CDK7 inhibitor (THZ1) alters the H3K27ac mark globally. In Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia, THZ1 disrupted the transcription of SE-associated gene XBP1 and eradicated leukaemia stem cells [52][47]. Several cancer subtypes that are sensitive to CDK7 inhibitor, such as oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma [53][48], triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) [54][49], MYCN-dependent neuroblastoma [37][50], and non-small cell lung cancer [55][51].

The ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers consist of the SWI/SNF, ISWI, INO80, and CHD families. SWI/SNF complex is a major regulator of distal lineage-specific enhancer activity [56][52]. Deletion of this complex in mouse embryonic fibroblasts results in H3K27ac loss and deactivation of the enhancer [56][52]. SWI/SNF ATPase degradation with AU-15330 (PROTAC degrader of SMARCA2 and SMARCA4) led to disruption of 3D loop interactions of SE with the promoter of AR, FOXA1, and MYC oncogenes, and decreased oncogenic expression in prostate cancer cells [57][53].

The INO80 complex occupies SEs and drives oncogenic transcription by regulating Mediator recruitment and nucleosome occupancy [58][54]. Silencing of INO80 results in downregulation of the SE-associated genes and inhibition of melanoma cell growth [58][54]. The NuRD complex subunit CHD4 localizes to SEs and regulates SEs accessibility to which PAX3-FOXO1 fusion protein binds and activates SE-driven gene transcription in fusion-positive rhabdomyosarcoma [59][55].

Anticancer drug Lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1) inhibitor (NCD38) activates GFI1-SE and induces lineage switch from erythroid to myeloid by activating differentiation in leukemic cells [60][61][56,57]. NCD38 evicts the histone repressive modifiers such as LSD1, CoREST, HDAC1, and HDAC2 from GFI1-SE [61][57]. Mediator-associated kinases such as CDK8 act as negative regulators of SE-mediated transcription. Mediator kinase inhibitor cortistatin A (CA) inhibits CDK8 and activates SE associate transcription of tumor suppressors and lineage controllers in AML [46][58]. As both I-BET151 (BET inhibitor) and CA have an opposing effect on SE-associated gene transcription, the authors suggest that cancer cells may depend on the dosage of SE-associated gene expression. The co-treatment did not neutralize the opposing effects but rather inhibited cell growth [46][58].

BET inhibitors such as FT-1101, RO6870810 (TEN-010), I-BET762, BMS-986158, OTX-015 (MK-8628), ABBV-075, AZD5153, BI 894999, ODM-207, ZEN-3694, PLX51107, NUV-868, TQB3617, and CPI-0610 are under clinical trials for haematological and solid tumors (http://clinicaltrials.gov/). Whereas CDK7 inhibitors such as SY-5609, XL102 and CT7001 are under clinical trials for advanced solid tumors (http://clinicaltrials.gov/). These inhibitors are in clinical trials either being tested alone or in combination with other drugs.

Transcription factor IIH (TFIIH) is a 10-subunit complex (core units XPB, XPD, p62, p52, p44, p34, and p8; dissociable units MAT1, CCNH, and CDK7) that regulates RNA Pol II transcription. Triptolide inhibits XPB subunit of the TFIIH complex and disrupts SE interactions and down-regulated SE-associated genes (MYC, BRD4, RNA Pol II, and COL1A2) in pancreatic cancer [62][59]. Minnelide (pro-drug of triptolide) is under phase II clinical trial for refractory pancreatic cancer (NCT03117920) and adenosquamous carcinoma of the pancreas (NCT04896073). Oral therapeutic drug GZ17-6.02 (602) comprises a mixture of curcumin, isovanillin, and harmine, that is known to affect the histone acetylation at SE-related genes in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is under Phase 1 clinical trial for advanced solid tumors and Lymphoma (NCT03775525) [63][60].

4. Drug Resistance to Super-Enhancer Drugs

Although SE drugs seem to be promising therapeutics, resistance to BRD4 inhibitor JQ1 has been reported in breast cancer and AML. SEs are gained in the established JQ1-resistant TNBC cell lines and are associated with enriched BRD4 recruitment to the chromatin in bromodomain independent manner. Increased expression of SE-associated genes such as BCL-xL makes them resistant to apoptosis compared to the parental cell line. The resistant cells are still addicted to BRD4 and are unaffected by JQ1, as JQ1 could not displace BRD4 from the chromatin due to an increase in stable pBRD4 levels binding with MED1 in resistant cells. This hyperphosphorylation could probably by the decrease in PP2A activity. Combined treatment of JQ1 with either BCL-xL inhibitor (ABT737), CK2 inhibitor (CX-4945) or PP2A activator (perphenazine) could overcome this resistance [64][73].

Long-term treatment of JQ1 resulted in the activation of drug-resistant genes in breast cancer cells. BRD4 associates with the repressive complex LSD1/NuRD1 and occupies H3K4me1 defined SEs. BRD4/LSD1/NuRD complex then represses the activation of drug-resistant genes such as WNT4, LRP5, BRAF, GNA13, and PDPK1 in breast cancer cells [65][74]. During long-term treatment with JQ1, the overexpressed PELI1 E3 ligase degrades LSD1, thus decommissioning the BRD4/LSD1/NuRD1 complex. This activates GNA13 and PDPK1 expression leading to drug resistance in breast cancer [65][74]. Combined treatment of BRD4 inhibitor and PELI1 inhibitor (BBT-401) may be effective in treating breast cancer.

By contrast, drug-resistant AML cells show yet another mechanism for acquiring drug resistance, in which MYC is activated in the absence of BRD4, possibly by activation of the Wnt pathway [66][67][75,76]. BET resistance in AML arises from the leukaemia stem cell population with upregulated Wnt signalling [66][75]. Despite the loss of Brd4, sustained oncogenic Myc expression equivalent to the control cells was observed, as β-catenin occupies the sites where Brd4 is decreased. Inhibition of Wnt signaling resensitizes the cells to BET inhibitors [66][75]. Similarly, another study reported that PRC2 complex suppression promotes BET inhibitor resistance in AML by remodeling the regulatory pathways and restoring the transcription of oncogenic Myc [67][76]. In response to BET inhibition, focal enhancer formed in established BET resistant cells drives Myc expression by recruiting activated Wnt machinery to compensate Brd4 loss. Overall, Wnt signaling acts as a driver and biomarker in acquired BET-resistant leukemia.

In the future, strategies will need to be devised to reduce or delay the development of drug resistance, for example, through combinations of cancer therapies where multiple epigenetic drugs are used to target potential avenues of drug resistance.