Serendipity is defined as the ability to recognize and evaluate unexpected information and generate unintended value from itan ability to notice, evaluate, and take advantage of unexpected information for survival purposes (both natural and social). The concept has been discussed for centuries. Still, it has only caught the attention of academia quite recently due to its strategic advantage in all aspects of life, such as daily life activities, science and technology, business and entrepreneurship, politics and economics, education administration, career choice and development, etc.

- serendipity

- serendipity as a strategic advantage

- innovation

- creativity

- typology

1. Concept

Serendipity has been acknowledged as one of the crucial factors behind many inventions or discoveries. Serendipitous moments can appear and become a strategic advantage [1] in all aspects of life, including daily life activities [2], business and entrepreneurship [3][4], science and technology [5], politics and economics [6], education administration [7], career choice and development [8], etc.

The earliest discussion of “serendipity” might be traced back to some versions of the story of Walpole [9]. Despite appearing centuries ago, the concept of serendipity has only been systematically studied quite recently. Serendipity can be defined as the abilityan ability to notice, evaluate, and take advantage of unexpected information for survival purposes (both natural and social) to recognize and evaluate unexpected information, and eventually create value from it [110]. More specifically, the scholars suggest that there are three typical characteristics of serendipity:

- Serendipity derives from unsought, unexpected, unanticipated, and unintentional events or information [1011];

- The information or event is out-of-the-ordinary, anomalous, surprising, and inconsistent with existing thoughts, findings, or theories [1112];

- The individual has to have the capacity and capability to recognize and capitalize the unexpected and anomalous events or information for solving a problem or finding an opportunity [1213].

2. Typology

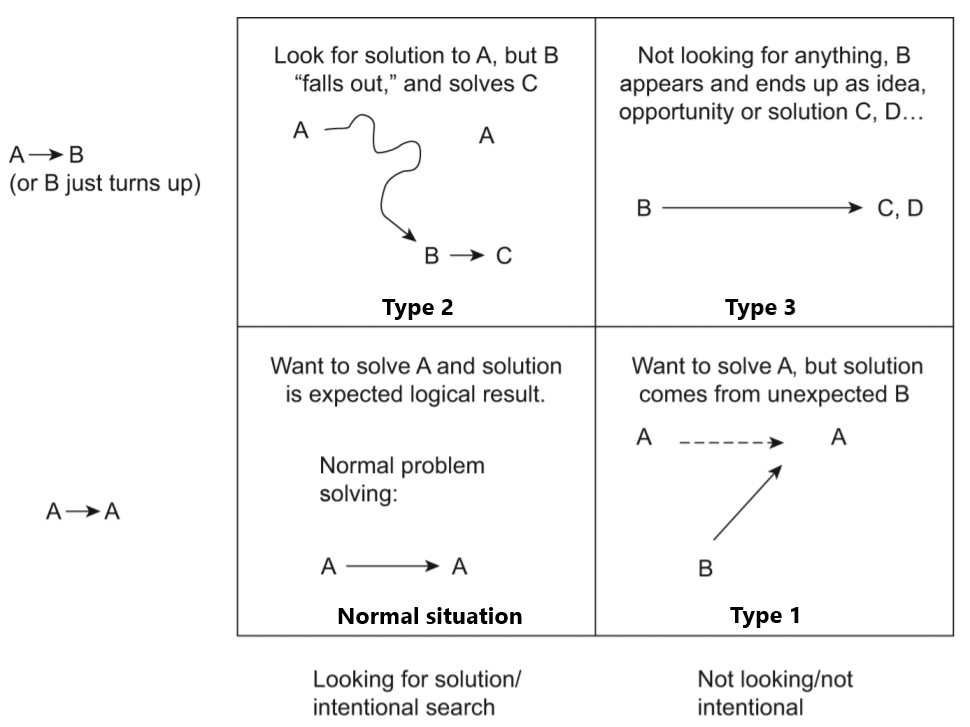

De Rond [1213] identified three types of serendipity for better studying and using the serendipity concept in innovation. The classification results from a 2x2 matrix between two categories: (1) the individual’s intention to search for information for solving a problem or finding an opportunity, and (2) the relation between the targeted problem and the solved problem. Nancy K. Napier and Vuong Quan Hoang [1] later demonstrated the matrix more explicitly with some additional symbols (see Figure 1). It should be noted that even though the matrix indicates four scenarios, there are only three types of serendipity because scenario ‘A → A’ is a normal problem-solving situation.

- Type 1: when an individual seeks solutions for problem A, they do not come from the expected sources ‘A’ but arise from unexpected sources ‘B’.

- Type 2: when an individual seeks solutions for problem A, the search reveals the unexpected and unsought information ‘B’. Information ‘B’ might be the solution for problem ‘C’.

- Type 3: when an individual does not seek solutions for any problems, information ‘B’ appears and lead to solutions or opportunities ‘C’.

Figure 1: Three types of serendipity. Modified based on [1].

3. Influential conditions

Context is critical for achieving serendipity. Scholars have identified factors influencing the possibility of a serendipitous moment happening at two levels:

- Organizational level

- Individual level

At the organizational level, both physical and cultural infrastructures are essential to encourage encounters of serendipity. Cunha et al. [1011] suggest that the “free flow of information” through different types of social networks, such as different units and hierarchical levels, might provide individuals with opportunities to reach out to new kinds of information and consequently face unexpected details. An organizational culture that promotes risk-taking, withholding of blame, and openness to a range of ideas can also improve the chances of encountering serendipity [1314]. In contrast, an organization with no openness and trust might thwart the individuals’ opportunities to face unexpected information or events.

An organization with a certain degree of tolerance to autonomy for experiments [1415], “controlled sloppiness” [1213], and minimal structure [1314] might create a more suitable environment for unintentional events to occur. The proactiveness of looking for serendipity is also another important organizational culture that facilitates the encounter of serendipity [1].

At the individual level, the factors that influence the possibility of encountering serendipity are the individual’s capabilities to notice and capitalize on unexpected information or events. These factors can be categorized into three groups: The first group consists of general characteristics that can help individuals be more capable of seeing and pursuing serendipity, such as motivation to work hard and perform well [7], a social network used effectively [1415], willingness to take risks [1516], and a good “grip on reality” in terms of feasibility [1617]. The second group consists of those involved in openness [1718] and curiosity [1819], while the third group includes those related to preparedness [1920] and alertness [1011].

References

- Napier NK, Vuong QH. (2013). Serendipity as a strategic advantage? In T Wilkinson & VR Kannan (Eds.), Strategic Management in the 21st Century (Vol. 1). Santa Barbara, California: Praeger.

- Van Andel P. (1992). Serendipity: “Expect also the unexpected”. Creativity and Innovation Management, 1(1), 20-32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8691.1992.tb00018.x

- Vuong, QH, Napier NK. (2015). Acculturation and global mindsponge: an emerging market perspective. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 49, 354-367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.06.003

- Vuong QH, Napier NK. (2014). Making creativity: the value of multiple filters in the innovation process. International Journal of Transitions and Innovation Systems, 3(4), 294-327. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTIS.2014.068306

- Barber B, Fox RC. (1958). The case of the floppy-eared rabbits: An instance of serendipity gained and serendipity lost. American Journal of Sociology, 64(2), 128-136. https://doi.org/10.1086/222420

- Taleb NN. (2007). The black swan: The impact of the highly improbable (Vol. 2). New York: Random house.

- Delcourt MA. (2003). Five ingredients for success: Two case studies of advocacy at the state level. Gifted Child Quarterly, 47(1), 26-37. https://doi.org/10.1177/001698620304700104

- Betsworth DG, Hansen JIC. (1996). The categorization of serendipitous career development events. Journal of Career Assessment, 4(1), 91-98. https://doi.org/10.1177/106907279600400106

- Merton RK, Barber E. (2011). The travels and adventures of serendipity. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Cunha MPE, Clegg SR, Mendonça S. (2010). On serendipity and organizing. European Management Journal, 28(5), 319-330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2010.07.001Quan-Hoang Vuong. (2022). A New Theory of Serendipity: Nature, Emergence and Mechanism. Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter.

- van Andel P, Bourcier D. (2002). Serendipity and abduction in proofs, presumptions and emerging laws. In M Mac & C Tillers (Eds.), The Dynamics of Judicial Proof (pp. 273-286). New York: Springer.Cunha MPE, Clegg SR, Mendonça S. (2010). On serendipity and organizing. European Management Journal, 28(5), 319-330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2010.07.001

- De Rond M. (2014). The structure of serendipity. Culture and Organization, 20(5), 342-358. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759551.2014.967451van Andel P, Bourcier D. (2002). Serendipity and abduction in proofs, presumptions and emerging laws. In M Mac & C Tillers (Eds.), The Dynamics of Judicial Proof (pp. 273-286). New York: Springer.

- Mendonça S, Cunha M, Clegg SR. (2008). Unsought innovation: serendipity in organizations. Paper presented at the Entrepreneurship and Innovation—Organizations, Institutions, Systems and Regions Conference, Copenhagen.De Rond M. (2014). The structure of serendipity. Culture and Organization, 20(5), 342-358. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759551.2014.967451

- Dew N. (2009). Serendipity in entrepreneurship. Organization Studies, 30(7), 735-753. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840609104815Mendonça S, Cunha M, Clegg SR. (2008). Unsought innovation: serendipity in organizations. Paper presented at the Entrepreneurship and Innovation—Organizations, Institutions, Systems and Regions Conference, Copenhagen.

- Diaz de Chumaceiro CL. (2004). Serendipity and pseudoserendipity in career paths of successful women: Orchestra conductors. Creativity Research Journal, 16(2-3), 345-356. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2004.9651464Dew N. (2009). Serendipity in entrepreneurship. Organization Studies, 30(7), 735-753. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840609104815

- Gaglio CM, Katz JA. (2001). The psychological basis of opportunity identification: Entrepreneurial alertness. Small Business Economics, 16(2), 95-111. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011132102464Diaz de Chumaceiro CL. (2004). Serendipity and pseudoserendipity in career paths of successful women: Orchestra conductors. Creativity Research Journal, 16(2-3), 345-356. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2004.9651464

- Williams EN, Soeprapto E, Like K, Touradji P, Hess S, Hill CE. (1998). Perceptions of serendipity: Career paths of prominent academic women in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 45(4), 379. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.45.4.379Gaglio CM, Katz JA. (2001). The psychological basis of opportunity identification: Entrepreneurial alertness. Small Business Economics, 16(2), 95-111. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011132102464

- Roberts RM. (1989). Serendipity: Accidental discoveries in science. New York: Wiley.Williams EN, Soeprapto E, Like K, Touradji P, Hess S, Hill CE. (1998). Perceptions of serendipity: Career paths of prominent academic women in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 45(4), 379. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.45.4.379

- Carter B. (2006). ‘One expertise among many’—working appreciatively to make miracles instead of finding problems: using appreciative inquiry as a way of reframing research. Journal of Research in Nursing, 11(1), 48-63. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987106056488Roberts RM. (1989). Serendipity: Accidental discoveries in science. New York: Wiley.

- Carter B. (2006). ‘One expertise among many’—working appreciatively to make miracles instead of finding problems: using appreciative inquiry as a way of reframing research. Journal of Research in Nursing, 11(1), 48-63. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987106056488