Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic immune-mediated systemic disease, which affects approximately 1% of the population and is characterized by a symmetrical inflammatory polyarthropathy. It has been demonstrated that drug-free remission (DFR) is possible in a proportion of RA patients achieving clinically defined remission (both on cs and b-DMARDS). Immunological, imaging and clinical associations with/predictors of DFR have all been identified, including the presence of autoantibodies, absence of Power Doppler (PD) signal on ultrasound (US), lower disease activity according to composite scores of disease activity and lower patient-reported outcome scores (PROs) at treatment cessation.

- rheumatoid arthritis

- remission

- drug-free remission

- b-DMARDs

- cs-DMARDs

- tapering

1. Introduction

2. Defining Remission in RA

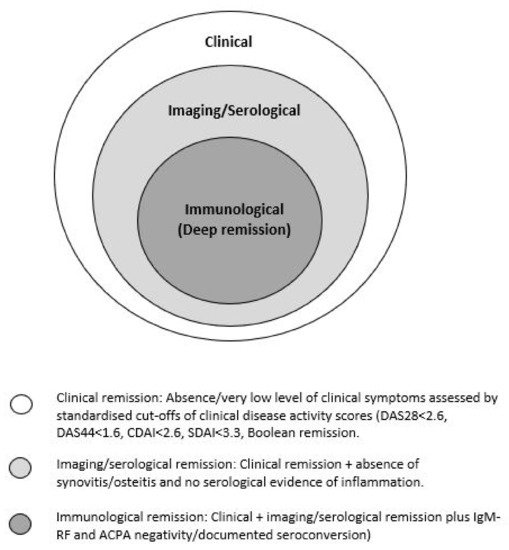

To be able to identify individuals who are more likely to achieve DFR, we first need to be able to define remission accurately. Remission in RA is currently defined clinically using a cut-off of the DAS28 (disease activity score). It incorporates a mathematical formula comprising the number of tender and swollen joints out of 28 (TJC28, SJC28), a serum marker of inflammation (e.g., C-reactive protein, CRP) and an optional measure of patients’ assessment of global health status (PGA) [7][13]. DAS28-remission has been defined as a score of <2.6 [8][9][14,15]. It is the standard measure used in clinical practice; however, it is not a precise assessment of remission. This score and tender joint count assessment may be influenced by physical comorbidities, e.g., osteoarthritis or psychosocial factors. Swollen joint counts may also be inaccurate in remission [10][16], while objective serological inflammatory markers (ESR and CRP) are non-specific to RA. Furthermore, the DAS28 joint count excludes the feet and ankles, therefore missing active disease in these areas [6][11]. It has been shown that some patients in remission do still have evidence of subclinical synovitis on musculoskeletal ultrasound (US) [11][12][13][14][17,18,19,20]. There have been multiple attempts to define clinical remission more stringently, including the ACR/EULAR 2011 Boolean remission criteria (TJC28, SCJ28, CRP and PGA all ≤1) [15][16][21,22], CDAI (TJC + SJC + PGA + Physician GA: remission = 0.0–2.8) [17][23] and SDAI (TJC + SJC + PGA + Physician GA + CRP: remission is ≤5) [18][24] scores (comprehensive and simplified disease activity scores, respectively); however, these still include subjective measures and potentially inaccurate joint counts [15][18][21,24]. The concept of ‘deep’ clinical remission has been considered (DAS28 < 1.98), which is suggested to reflect the absence of biological inflammation; however, longitudinal outcome data relating to this target have not yet been studied prospectively [19][25]. Physical examination is known to have a low sensitivity for the detection of mild synovitis, such as that found in clinical remission; however, musculoskeletal US has proven to be an excellent tool to identify subclinical inflammation that is associated with risk of relapse and structural damage [20][21][22][26,27,28]. Despite this, the definition of what constitutes imaging remission remains challenging [13][22][23][19,28,29]. More recently, immunological status has been shown to predict the likelihood of sustained remission in RA [24][25][30,31]. This adds another potential dimension to consider when defining the remission state in RA. Schett et al. [26][7] have recently introduced the concept of ‘multi-level’ remission aimed to characterize remission more precisely (Figure 1). It involves the achievement of different levels/depths of remission. It suggests that a state of deep remission may be attained if all three categories are achieved; however, this has not yet been used prospectively.

3. DFR Remission in Patients with RA Treated with cs-DMARDs

DMARDs are indicated for the treatment of inflammatory arthritis, e.g., RA; however, they are also used to treat other disorders [27][32]. cs-DMARDs are typically used as first-line agents, alone or in combination. Commonly used cs-DMARDs include methotrexate (MTX), hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), leflunomide (LEF) and sulfasalazine (SSZ). They are mostly oral preparations (except for MTX, which can also be injected subcutaneously) [28][33]. Some of the earliest data on withdrawing cs-DMARDS come from historical observational studies. These studies often focus on older conventional cs-DMARDs, which are no longer used in first-line RA treatment, e.g., gold and d-penicillamine [29][30][34,35]. It has been demonstrated that DFR is possible in a minority of cases. Most of the evidence for discontinuing cs-DMARDs to achieve sustained DFR comes from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for patients with stable RA on a range of monotherapies [29][31][32][33][34][34,36,37,38,39]. Many of the DMARDs studied, however, are now rarely used in practice. Additional evidence comes from RCTs and observational studies in which a step-down approach in treatment was followed (combination DMARDs reduced to monotherapy). These demonstrated sustained clinical response to treatment after tapering in early RA patients [35][36][37][38][40,41,42,43]. Table 1 summarizes the studies discussed.|

Study |

Design |

Authors |

n |

Treatment/Intervention |

RA Disease Duration |

Remission Criteria |

%DFR Remission |

DFR-Predicting Factors |

Follow Up Period |

|---|

5. DFR Remission in Patients with RA Treated with Biological Therapies (b-DMARDs)

|

Study |

Design |

Authors |

n |

Treatment/Intervention Drug Withdrawn in Italics |

RA Disease Duration |

Remission Criteria |

%DFR Remission in Biologic Treatment Arm |

DFR Predicting Factors |

Follow Up Period |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Can disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs be discontinued in long standing rheumatoid arthritis? A 15-year follow-up |

Observational |

Tiippana et al., 2010 |

70 |

Single or combination Cs-DMARDS tapered |

Early RA |

5/6 ARA criteria fulfilled. |

|||||||||

|

IVEA |

Double blind RCT | 16% |

Quinn MQ et al., 2006 |

20 | N/A |

15 years |

|||||||||

1. | Infliximab | + MTX |

2. MTX |

6 months |

DAS28 |

70 |

- |

12 months |

Prevalence and predictive factors for sustained disease-modifying antirheumatic drug-free remission in rheumatoid arthritis: results from two large early arthritis cohorts |

Observational |

|||||

|

BeSt |

RCT |

van der Woude et al., 2009 |

van den Broek M et al., 2011 Leiden EAC cohort: 454 British EAC Cohort: 895 |

128 Single or combination Cs-DMARDS tapered |

4th study arm: Combination with (MTX/SSZ/HcQ) |

infliximab Early RA |

23 months Had to fulfil 3 criteria: (1) No current use of DMARDs/corticosteroids, (2) No swollen joints, and (3) Classification as DMARD-free remission by the patient’s rheumatologist. |

Leiden EAC cohort: 15% British EAC Cohort: 9.4% |

DAS44 |

56 Absence of autoantibodies ((ACPA and IgM-RF) and short symptom duration at presentation |

Lower baseline HAQ Minimum of 1 year after discontinuation of DMARD therapy |

||||

ACPA negative | Lower baseline disease activity | Younger age | Non-smoker |

24 months |

KIMERA |

||||||||||

|

IDEA | Observational |

Double blind RCT Jung et al., 2020 |

Nam JL et al., 2014 234 |

112 Single or combination therapy with cs DMARDs; methotrexate (MTX)/sulfasalazine combined with high-dose glucocorticoid; MTX combined with TNF-inhibitors tapered |

1. Infliximab +MTX 2. MTX + single dose IV methylprednisolone Early RA |

(1) Non-use of cs or bDMARDs and glucocorticoids, (2) DAS28 <2.6, and (3) no swollen joints. |

78 weeks 46.1% |

Early RA and lower disease activity (DAS28 <2.26) at csDMARD withdrawal |

DAS44 |

76% 48 months |

|||||

- | 78 weeks |

Randomized placebo-controlled study of stopping second-line drugs in RA |

RCT |

||||||||||||

|

HONOR |

Open label non randomized |

Ten Wolde et al., 1996 |

Yamaguchi A et al., 2020 285 |

52 Placebo or withdrawal of at least one 2nd line cs-DMARD (chloroquine, HCQ, gold, d-penicillamine, SSZ, AZA or MTX) |

Adalimumab Established RA. Median duration 8–9 years. |

7 years 5/6 ARA criteria fulfilled |

DAS28 62% |

21 Lower maintenance dose of second line drug and absence of RF |

A baseline DAS28 of <2.22 or <1.98 52 weeks |

||||||

Shorter disease duration | 60 months |

D-penicillamine withdrawal in rheumatoid arthritis |

Double blind RCT |

Ahern et al., 1984 |

|||||||||||

|

RRR * |

Observational |

Tanaka Y et al., 2010 |

38 |

114 Tapering of d-penicillamine |

Infliximab Established RA (6–11 years) |

6 years 5/6 ARA criteria fulfilled |

LDA 21% |

None |

12 months |

||||||

55 | A baseline DAS28 of <2.22 or <1.98 | 12 months |

BeST |

Multi center randomized single blind trial |

|||||||||||

|

OPTIMA | Markusse et al., 2015 |

RCT 508 |

Smolen J et al., 2013 MTX/combination cs DMARD/ combination cs-DMARD +prednisolone/combination cs DMARD with MTX and Infliximab |

1032 |

Adalimumab + MTX Early disease (symptom duration < 2 years) |

≤12 months DAS44 <1.6 |

14% |

Absence of ACPA and using MTX rather than SSZ as the last csDMARD before withdrawal |

10 years |

||||||

DAS28 | 66% | Good baseline functional status |

52 weeks |

tREACH |

RCT |

Kuijper et al., 2016 |

Triple cs-DMARD (MTX, SSZ and HCQ) with glucocorticoid bridging or MTX monotherapy with glucocorticoid bridging | ||||||||

|

PRIZE |

Double blind RCT |

Emery P et al., 2014 281 |

TNFi and MTX if the DAS28 was >2.4. |

306 |

1. ½ dose Etanercept + MTX 2. Placebo + MTX 3. Placebo alone Early RA |

≤12 months DAS28 <1.6 |

DAS2 2.4% |

23–40% N/A |

2 year |

||||||

- | 39 weeks |

IMPROVED |

RCT |

Heimans et al., 2016 |

|||||||||||

|

CERTAIN |

Double blind RCT |

Smolen J et al., 2015 |

610 |

194 MTX and prednisolone, then tapered |

Early RA or Undifferentiated arthritis |

DAS44 <1.6 |

21% |

Absence of ACPA |

1. Certolizumab + MTX 2. Placebo |

6 months–10 years |

CDAI |

- 2 year |

|||

18.8% | 52 weeks |

BioRRA |

Interventional cohort study |

Baker et al., 2019 |

44 |

Cessation of cs-DMARDs |

Established RA |

DAS28-CRP < 2.4 |

48% |

Absence of RF, shorter time from diagnosis to starting first DMARD, shorter symptom duration at time of diagnosis, longer disease duration fulfilment of ACR/EULAR Boolean remission criteria and longer time since last DMARD change Absence of genes within peripheral CD4+ T cells; FAM102B and ENSG00000227070 Presence of gene within peripheral CD4+ T cells: ENSG00000228010 |

6 months |

4. Predicting DFR for Patients Receiving Treatment with cs-DMARDs

Patients with RA in remission on TNF blockers: when and in whom can TNF blocker therapy be stopped? | |||||||||

Observational | |||||||||

Saleem et al., 2011 |

47 |

TNFi (Various) + MTX 1. Initial therapy 2. Delayed therapy |

12 months |

DAS28 |

59%15% |

Male gender First line TNFi Shorter disease duration Higher and naïve T-cells and fewer IRCs at baseline |

24 months |

||

|

EMPIRE |

Double blind RCT |

Nam et al., 2013 |

110 |

1. Etanercept + MTX 2. MTX + placebo |

≤3 months |

DAS28 |

28.1% |

Starting TNFi earlier in disease course |

52 weeks |

|

TARA |

Single blind RCT |

Van Mulligen et al., 2020 |

189 94 DMARD 95 TNFi |

TNFi or csDMARD (Various) 1. csDMARD taper first 2. TNFi taper first |

Not stated |

DAS44 |

15% |

- |

24 months |

|

AVERT |

Double blind RCT |

Emery P et al., 2015 |

351 |

Abatacept + MTX |

<1 year |

DAS28 |

15% |

Lower baseline PRO scores |

18 months |

|

DREAM |

Observational |

Nishimoto N et al., 2014 |

187 |

Tocilizumab |

7.8 years |

LDA |

9% |

Lower multi-biomarker assay scores (serological) RF negative |

12 months |

|

ACT RAY |

RCT |

Huizinga TW et al., 2015 |

556 |

Tocilizumab |

8 years |

DAS28 |

6% |

Shorter disease duration, few/absent erosions |

12 months |

|

RETRO |

RCT |

Haschka J et al., 2016 |

101 |

Various |

NK |

DAS28 |

48.1% |

ACPA negative Lower baseline disease activity Male gender Lower multi-biomarker assay scores (serological) RF negative |

12 months |

|

PredictRA |

Double blind RCT |

Emery et al., 2020 |

122 |

Adalimumab taper vs. withdrawal |

Mean 12.9 years |

DAS28 |

55% (withdrawal arm) |

- |

36 weeks |

|

ANSWER |

Cohort |

Hashimoto et al., 2018 |

181 |

Various |

NK |

DAS28 |

21.5% |

Boolean remission at baseline Sustained remission period No glucocorticoid use at time of discontinuation TNFi discontinuation (vs. other b-DMARD) |

12 months |

* NK = not known.