Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Amina Yu and Version 1 by Rong Peng.

Although China launched long-term care insurance (LTCI) pilot program in 2016, there are great challenges associated with developing a sustainable LTCI system due to limited financial resources and a rapid increase in the aging population. It is needed to evaluate the impact of LTCI policy development from diverse perspectives and using various evaluation methods.

- long-term care insurance

- policy strength

- pilot scheme

1. Introduction

With the rapid growth of the aging population, the corresponding increase in long-term care (LTC) needs has posed great challenges to the sustainability of providing and financing care [1]. While the long-term care expenditure has kept growing over recent years, a large number of older adults with a disability lack general long-term care and financial support [2]. For example, the expenditure of LTC services reached 1.5% of gross domestic product (GDP) across OECD countries in 2019, 30–50% of older people with a disability reported that they did not receive sufficient LTC support [2]. In order to finance long-term care, some countries, such as Germany, Japan and South Korea, have introduced public long-term care insurance (LTCI) during recent decades. In China, the proportion of the population aged 65 or above rose to 13.5% in 2020 [3], and 52.71 million older adults have at least one limitation on daily life activity [4]. Since the majority of older adults with a disability are cared for by family members, they are accompanied by heavy family burden [5] and unmet long-term care [6].

To explore different methods of setting up a long-term care insurance (LTCI) system, China launched an LTCI pilot program in 15 cities in June 2016 [7]. Although China has become the second largest economy in the world in terms of GDP (USD 14.73 trillion in 2020, equivalent to 70% of that of the United States and accounting for 17.42% of the world), China’s GDP per capita was USD 11,300 in 2020, which is much lower than that of Germany in 1995 (USD 25,100), Japan in 2000 (USD 26,900), and Korea in 2008 (USD 27,464), when their respective LTCI systems were established. From the perspective of population aging trends, 13.5% of the population were over 65 years old in China according to the data of the seventh census in 2020. The proportion of the population over 65 years old was higher than that of Korea in 2008 (10.3%), close to that of Germany in 1995 (15.5%), and slightly lower than that of Japan in 2000 (17.4%) at the time of the establishment of their LTCI systems. Thus, the establishment of the LTCI system reflects the Chinese government’s willingness to actively deal with population aging.

It was reported that the LTCI pilot program in China had some impact after its implementation [8,9,10][8][9][10]. Using some pilot sites as examples, 752.8 thousand people in Chengdu received LTCI benefits amounting to yuan 843 million (equivalent to USD 132 million), which reduced the financial burden of families with disabled members by 44.31% [8]. The medical expenses of families with disabled members in Nantong were reduced from yuan 162 million (USD 25.5 million) to yuan 99.7 million (USD 15.7 million; about 38.5%) since the launch of the LTCI pilot [9]. Shanghai promoted the development of a long-term care industry by formulating action plans to encourage employment in this industry and trained 68 thousand nursing staff [10]. However, the Chinese central government has yet to establish a nationwide LTCI system but rather decided to expand the LTCI pilot sites to 14 other cities in China in 2020 [11]. At the current stage, China’s LTCI demonstration in the first 15 pilot cities has not accumulated sufficient evidence to formulate an appropriate policy scheme in line with the actual situation of the entire nation [12].

The major factors for the Chinese government to consider when establishing the LTCI are the economic development level and population aging [7,11][7][11]. There exists a complex interaction between LTCI policy, economic development, and population aging. On the one hand, the launch of LTCI increases the labor supply and stimulates the development of related industries. For instance, up to the end of 2020, the pilot city of Shanghai built up its LTC service supply market to include 750 nursing homes and 436 family-based care institutions [10]. The LTCI provides financial reimbursement to the persons receiving care in elder care institutions and residential care facilities. On the other hand, the economic development level determines the ability to finance the LTCI, which is related to the feasibility of the system [5,12][5][12]. Population aging is the main determinant of demand for LTCI and is related to the necessity of the system [7,11][7][11]. The interaction between the LTCI policy, economic development, and population aging trigger dynamic interactions in the internal structure, which is regarded as a coupling coordination mechanism.

Coupling refers to the measure by which two or more entities depend on each other, which originates from the testing and study of the interaction and correlation of multiple systems in physics [13]. Coordination can be used to describe the interaction between two or more systems that are not simply linearly correlated with each other [14]. The coupling coordination degree is a term that can be used to measure the coordination relationship [15]; it is a suitable instrument for analyzing the mutual effects between LTCI policy, economic development, and population aging. ThisIt studywas examined the coupling coordination between LTCI policy, economic development, and population aging to assess the sustainability of China’s LTCI system.

Compared with those of developed countries, China’s current social pension security system, pension service system, pension service facilities, and human and capital reserves are not well prepared to deal with the problem of rapid population aging under the condition of “getting old before getting rich” [16]. It was announced that an LTCI policy framework adapted to China’s economic development level and aging trend will be formed during the 14th Five Year Plan Period (2021–2025) [11]. One of the challenges now faced by China’s health care system is to determine the policy framework of an LTCI in the context of its current population aging and economic development levels. After all, there are huge differences between different regions in terms of economic development and population aging [17]. The central government has put forward guidelines with a large number of policy options to encourage local governments to carry out LTCI pilot programs. Assessing the sustainability of the LTCI system can not only help to develop a nationwide LTCI system but also provide insights for other countries facing similar challenges.

2. LPriterature Reviewmary Concerns Associated with an LTCI System

The primary concerns associated with an LTCI system are related to the future sustainability and affordability of long-term care financing and the equality of the current funding mechanism [1,2][1][2]. Government funding is increasingly burdened by the financing of long-term care, especially for the countries with a social LTCI system, such as in Germany and Japan [18,19][18][19]. Currently, some countries have carried out reforms on their LTCI systems to make them sustainable by increasing the individual payment or reducing the reimbursement rate to mitigate the government’s burden [18]. Generally speaking, how to keep the LTCI system sustainable in the context of population aging is a common problem worldwide [20,21][20][21].

Since China launched the LTCI pilot program, many studies have been compared the policy documents issued by local governments to assess the implementation schemes of LTCI in pilot cities. They have found that the insurance coverage, eligibility, financing source, care service, benefits, and payments have much in common as well as some differences [22,23][22][23]. Several researchers have conducted empirical studiones to evaluate the performance of the LTCI implementation in China. Zhang and Yu (2019) examined the willingness of the population to formally implement the LTCI policy in China [24]. Lei et al. (2022) found that older adults were less likely to report unmet activities of daily living needs in terms of care and that the intensity of informal care in pilot cities was reduced after the implementation of LTCI [25]. Feng et al. (2020) used medical insurance data to assess the effect of Shanghai’s LTCI pilot system on the residents’ medical expenses. It was found that China’s LTCI system had significantly reduced residents’ medical expenses [26]. Peng et al. (2021) used the system dynamics (SD) methodology to examine the impact of current and future LTC policies on the family care burden in China [27].

However, there are few quantitative evaluations on the strengths and weaknesses of the LTCI policy modeling of pilot cities in China. It is unclear which pilot city’s LTCI policy model is more valuable as a reference for China to establish a nationwide LTCI system that adapts to the current level of economic development and population aging. Since the purpose of the LTCI pilot is to establish a unique LTCI system suitable for China’s economic development and population aging trend, it is worthwhile evaluating the degree of coupling and coordination of the current LTCI policy model with economic development and population aging to identify key factors affecting the demographic and economic adaptability of the LTCI policy model.

The coupling coordination model has been widely used to evaluate the coordination between different systems. The major topic in the related research focuses on the coupling coordination between the economic, social, and environmental systems [28,29,30][28][29][30]. A few studies have ebeen explored that the coupling coordination between health care institutions and citizens’ living standards [31], and between populations and urbanization settings [32]. To ourthe knowledge, there is no research investigating LTCI policy strength and coupling coordination between LTCI policy, population aging, and economic development in China.

3. Characteristics of China’s LTCI Pilot Scheme

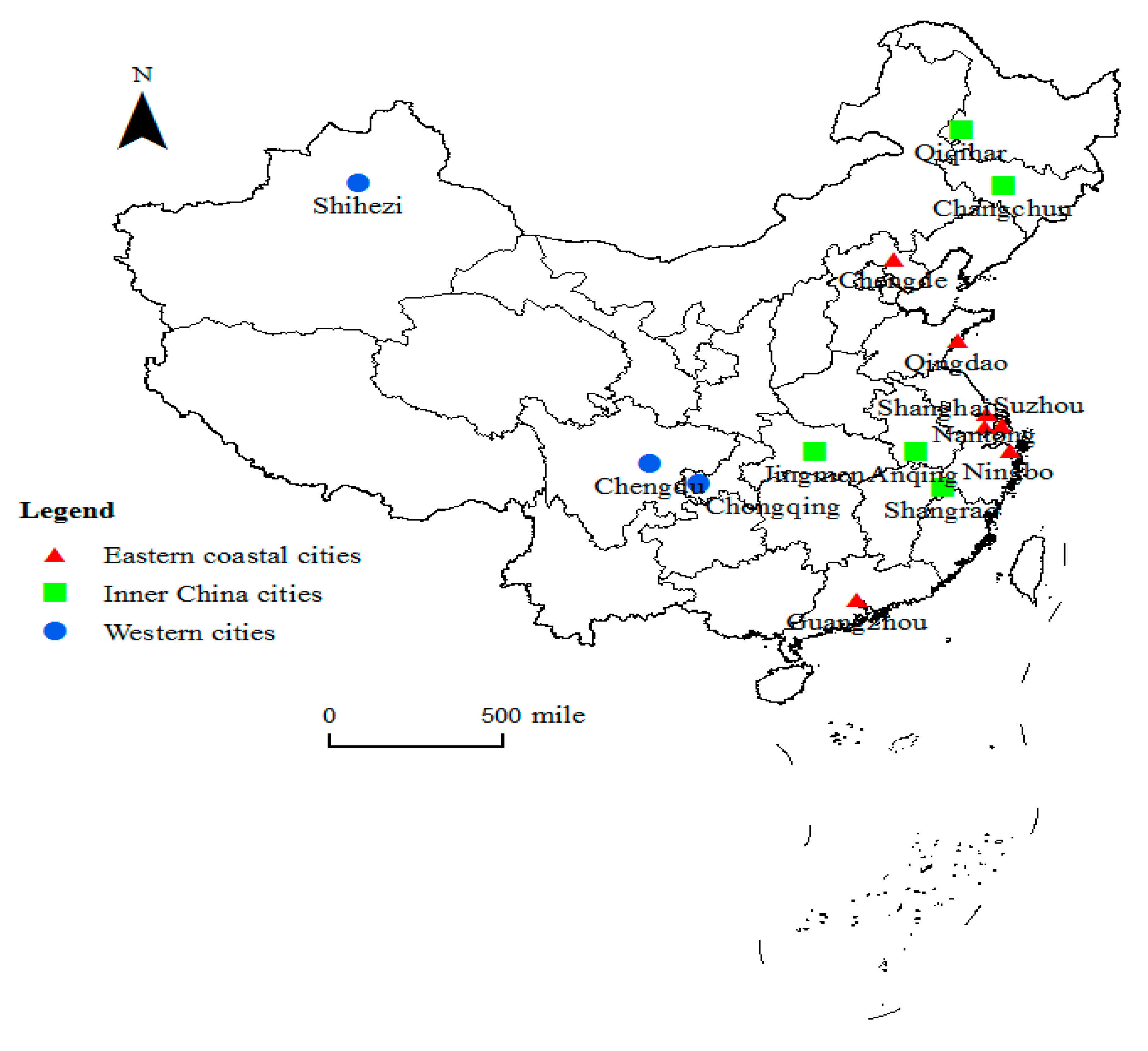

The first 15 pilot cities are distributed in three regions of China: eastern coastal cities (Chengde, Shanghai, Nantong, Suzhou, Ningbo, Qingdao, and Guangzhou), inner China cities (Changchun, Qiqihar, Jingmen, Anqing, and Shangrao), and western cities (Chongqing, Chengdu, and Shihezi) (Figure 1). It can be seen that the pilot cities are mainly located in central and eastern China.

Figure 1.

Locations of the first 15 pilot cities of the LTCI in China.

The pilot LTCI scheme mainly stipulates the coverage, financing mechanisms, and benefits packages. All the pilot LTCI programs cover participants who are participants of the Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance. Some LTCI cities have expanded the insurance to cover participants who are participants of the Urban–Rural Resident Basic Medical Insurance. These cities are Nantong, Shangrao, Shihezi, Suzhou, Qingdao, Jingmen, and Shanghai. The main source of LTCI funding is medical insurance funds, followed by government subsidies, individual contributions, and employer contributions. Among them, Changchun, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Ningbo rely entirely on medical insurance funds.

The benefit package, including care services and expense reimbursement, varies from city to city. The beneficiaries of all pilot cities include persons with severe disabilities, and they are extended to people with dementia in some cities (Shanghai, Nantong, Ningbo, Qingdao, and Chengdu). Most cities cover institutional care and home care (Changchun and Ningbo only cover institutional care). It is usually preferred to be reimbursed home care at a higher rate or a higher payment proportion. For example, the reimbursement rate of home care services is 90% in Shanghai, higher than that of institutional care services (85%). The services of all pilot cities include daily living care, and some cities also include preventive care, rehabilitation nursing, psychological counseling, medical care, and hospice care. All cities reimburse a fixed amount on a daily or monthly basis, with a maximum limit on the total number of hours or days.

References

- Oliveira Hashiguchi, T.; Llena-Nozal, A. The Effectiveness of Social Protection for Long-Term Care in Old Age: Is Social Protection Reducing the Risk of Poverty Associated with Care Needs? OECD Health Working Papers 2020, No. 117; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020.

- OECD. Health at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021.

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Statistical Yearbook 2021; Statistical Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Luo, Y.; Su, B.; Zheng, X. Trends and challenges for population and health during population aging—China, 2015–2050. China CDC Wkly. 2021, 3, 593–598.

- Wiener, J.M.; Feng, Z.; Zheng, N.T.; Song, J. Long-term care financing: Issues, options, and implications for China. In Options for Aged Care in China: Building an Efficient and Sustainable Aged Care System; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 191–213.

- Peng, R.; Wu, B.; Ling, L. Undermet needs for assistance in personal activities of daily living among community-dwelling oldest old in China from 2005 to 2008. Res. Aging 2015, 37, 148–170.

- Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security. Guiding Opinions on Initiating the Long-Term Care Insurance Pilots; Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Li, H.; Wang, M.; Shen, S. Long-Term Care Insurance, Promoting the Development of the Aged-Care Industry. In the People’s Daily. China. 2021. Available online: http://paper.people.com.cn/rmrb/html/2021-08/13/nw.D110000renmrb_20210813_1-19.htm (accessed on 6 February 2022).

- Xu, C.; Fan, R.; Chen, K. Speeding Up Completion of a Comprehensive Well-Off Society, Nantong Medical Insurance Bravely Bears Responsibilities. In Xinhua Daily; Xinhua Daily Press Group: Jiangsu, China, 2019; Available online: http://xhv5.xhby.net/mp3/pc/c/201910/08/c693168.html (accessed on 6 February 2022).

- Huang, Z.; Jin, H.; Li, C. Pilot path and effect of long-term care insurance in Shanghai. China Health Insur. 2021, 3, 48–51.

- National Health Security Administration. Guidelines of the National Health Insurance Administration and the Ministry of Finance on Expanding the Pilot Long-Term Care Insurance System; Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Feng, Z.; Glinskaya, E.; Chen, H.; Gong, S.; Qiu, Y.; Xu, J.; Yip, W. Long-term care system for older adults in China: Policy landscape, challenges, and future prospects. Lancet 2020, 396, 1362–1372.

- Gai, M.; Wang, Y.; Ma, G.; Hao, H. Evaluation of the coupling coordination development between water use efficiency and economy in Liaoning coastal economic belt. J. Nat. Resour. 2013, 28, 2081–2094.

- Fang, C.; Liu, H.; Li, G. International progress and evaluation on interactive coupling effects between urbanization and the eco-environment. J. Geogr. Sci. 2016, 26, 1081–1116.

- Liu, L.; Caloz, C.; Chang, C.-C.; Itoh, T. Forward coupling phenomena between artificial left-handed transmission lines. J. Appl. Phys. 2002, 92, 5560–5565.

- Johnston, L.A. “Getting old before getting rich”: Origins and policy responses in China. China Int. J. 2021, 19, 91–111.

- Dong, X.; Simon, M.A. Health and aging in a Chinese population: Urban and rural disparities. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2010, 10, 85–93.

- Wang, Q.; Tang, M.; Cao, H. Comparative study on the long-term nursing insurance pilot service projects in China. Health Econ. Res. 2018, 11, 38–42.

- Blank, F. The state of the German social insurance state: Reform and resilience. Soc. Policy Adm. 2020, 54, 505–524.

- Olivares-Tirado, P.; Tamiya, N. Trends and Factors in Japan’s Long-Term Care Insurance System: Japan’s 10-Year Experience; Springer Science and Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014.

- Costa-Font, J.; Courbage, C.; Zweifel, P. Policy dilemmas in financing long-term care in Europe. Glob. Policy 2017, 8, 38–45.

- Galiana, J.; Haseltine, W.A. Aging Well: Solutions to the Most Pressing Global Challenges of Aging; Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2019.

- Yang, W.; Chang, S.; Zhang, W.; Wang, R.; Mossialos, E.; Wu, X.; Cui, D.; Li, H.; Mi, H. An Initial analysis of the effects of a long-term care insurance on equity and efficiency: A case study of Qingdao city in China. Res. Aging 2021, 43, 156–165.

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, X. Evaluation of long-term care insurance policy in Chinese pilot cities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3826.

- Lei, X.; Bai, C.; Hong, J.; Liu, H. Long-term care insurance and the well-being of older adults and their families: Evidence from China. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 296, 114745.

- Feng, J.; Wang, Z.; Yu, Y. Does long-term care insurance reduce hospital utilization and medical expenditures? Evid. China. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 258, 113081.

- Peng, R.; Wu, B. The impact of long-term care policy on the percentage of older adults with disabilities cared for by family members in China: A system dynamics simulation. Res. Aging 2021, 43, 147–155.

- Cui, D.; Chen, X.; Xue, Y.; Li, R.; Zeng, W. An integrated approach to investigate the relationship of coupling coordination between social economy and water environment on urban scale—A case study of Kunming. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 234, 189–199.

- Zhang, L.; Wu, M.; Bai, W.; Jin, Y.; Yu, M.; Ren, J. Measuring coupling coordination between urban economic development and air quality based on the Fuzzy BWM and improved CCD model. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 75, 103283.

- Ma, L.; Chen, M.; Fang, F.; Che, X. Research on the spatiotemporal variation of rural-urban transformation and its driving mechanisms in underdeveloped regions: Gansu Province in western China as an example. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 50, 101675.

- Ren, W.; Tarimo, C.S.; Sun, L.; Mu, Z.; Ma, Q.; Wu, J.; Miao, Y. The degree of equity and coupling coordination of staff in primary medical and health care institutions in China 2013–2019. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 236.

- Gan, L.; Shi, H.; Hu, Y.; Lev, B.; Lan, H. Coupling coordination degree for urbanization city-industry integration level: Sichuan case. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 58, 102136.

More