Breast cancer represents the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the female population, despite continuing advances in treatment options that have significantly accelerated in recent years. Conservative treatments have radically changed the concept of healing, also focusing on the psychological aspect of oncological treatments. In this scenario, radiotherapy plays a key role. Brachytherapy is an extremely versatile radiation technique that can be used in various settings for breast cancer treatment. Although it is invasive, technically complex, and requires a long learning curve, the dosimetric advantages and sparing of organs at risk are unequivocal. Literature data support muticatheter interstitial brachytherapy as the only method with strong scientific evidence to perform partial breast irradiation and reirradiation after previous conservative surgery and external beam radiotherapy, with longer follow-up than new, emerging radiation techniques, whose effectiveness is proven by over 20 years of experience.

- brachytherapy

- muticatheter interstitial brachytherapy

- APBI

- accelerated partial breast irradiation

- breast salvage treatment

- breast cancer

- ipsilateral breast recurrence

- brachytherapy boost

- breast reirradiation

1. Introduction

2. Implant Technique and Treatment Delivery

2.1. Catheter Insertion

The standard procedure for breast catheter insertion consists of a transcutaneous approach. Metallic needles are manually inserted around the open/close cavity created during a lumpectomy, using a plastic guide template with needle holes to achieve geometric dose distribution. The needles are spaced to form equilateral triangles of 12–20 mm, according to the Paris System [12], then inserted in two to four planes, starting from the inferior plane to ensure an acceptable dose coverage to the deep tumor cavity under direct visualization (intraoperative), or guided by ultrasound images (postoperative). The deepest implant plane should be dorsal to the seroma, while the most ventral one should be placed between the skin surface and the seroma. Special care must be taken so that the needles are positioned at a distance of at least 1 cm from the skin surface to avoid late skin toxicity. At the end of the procedure, in the case of an open cavity (seroma), the needles can be replaced by plastic tubes. The number of applicators and tubes varies according to the size of the tumor cavity and breast anatomy (Figure 1) [13,14][13][14]. Once the needle positioning has been completed and the adequacy of the implant has been verified, a computed tomography (CT)-based simulation for target volume delineation and radiotherapy planning will be performed. If no appropriate target volume coverage is detected on the simulation CT scan, a few additional catheters may be inserted freehand without the use of a template.

2.2. Target Definition and Delineation

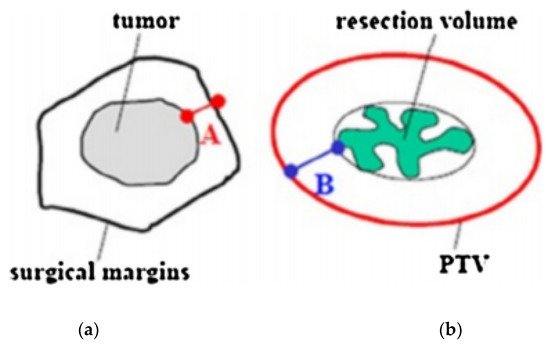

Recently, guidelines for patients’ selection and brachytherapy target volume delineation after breast-conserving surgery with both a closed and an open cavity, as well as dose recommendations according to risk factors, were provided by the GEC-ESTRO Breast Cancer Working Group [15,16,17][15][16][17]. A CT scan with a 2–3 mm slice thickness is required to locate the surgical clips, which are needed to properly outline the target volume. Treatment planning begins with the delineation of an estimated target volume, taking into account preoperative imaging (mammography, breast ultrasound, and breast magnetic resonance if available), the surgical scar, the position of the surgical clips, and surgical margins. The clinical target volume (CTV) is defined with the addition of an isotropic, a total safety margin of 20 mm to the estimated target volume, and subtraction of the surgical margin. The thoracic wall and the skin must not be a part of the CTV. No additional margin to obtain the planning target volume (PTV) is necessary if the tumor bed and surgical clips are clearly visible. In the case of uncertainties ranging from 5 to 10 mm, additional margins can be delineated (Figure 2) [18,19][18][19].

2.3. Dosimetry

The total dose to the target volume is nowadays delivered in the following two different ways: low-intensity pulses repeated every hour for up to a few days (pulse-dose-rate (PDR) brachytherapy); or a few, consecutive, high-dose fractions (HDR), the most used. Various radioisotopes with specific properties in terms of half-life and energy can be used. The most commonly applied in modern brachytherapy are iridium-192, cobalt-60, iodine-125, and palladium-103. In order to select an appropriate isodose, the dose distribution has to be uniquely normalized. The dwell times are calculated on the basis of volumetric dose constraints. In the case of HDR and PDR BCT, geometric optimization for volume implants should keep the dose non-uniformity ratio (V100/V150) below 0.35 (0.30 ideally) [13]. The volume of PTV receiving 100% of the prescribed dose must be greater than 90% (coverage index ≥ 0.9), with a volume of PTV receiving 150% of the prescribed dose (V150%) less than 30%, and a volume receiving 200% of the prescribed dose (V200%) less than 15%, dose non-homogeneity ratio (V150/V100) < 0.35 (ideally 0.30). The maximum acceptable dose to the skin surface should be less than 70% of the prescribed dose. Table 1 summarizes the GEC-ESTRO normal tissue dose constraints [20] (Table 1).| Organs | Constraints |

|---|---|

| Ipsilateral no target breast tissue | V90 < 10% V50 < 40% |

| Skin | D1 cm3 < 90% D0.2 cm3 < 100% |

| Ribs | D0.1 cm3 < 90% D1 cm3 < 80% |

| Heart | MHD < 8% D0.1 cm3 < 50% |

| Ipsilateral lung | MLD < 8% D0.1 cm3 < 60% |

3. Brachytherapy Doses

In 2018, the ESTRO-ACROP expert panel published the following recommendations for breast brachytherapy doses [20]. Recommended radiation schedules for HDR-BCT-based lumpectomy boost are as follows: a biologically equivalent total dose (BED2 for alpha/beta ratio = 4–5 Gy) in the range of 10–20 Gy from 1 to 4 fractions should be selected. The panel of experts preferably recommends 2 × 4–6 Gy, or 3 × 3–5 Gy scheduled 2 times per day, with an interval between fractions of at least 6 h, and a total treatment time of 1–2 days, or a single fraction of 7–10 Gy, depending on the desired total EQD2. Recommended schedules for APBI/accelerated partial breast reirradiation (APBrI) with HDR are as follows: 10 fr 3.4 Gy, or 8 fr 4 Gy, or 7 fr 4.3 Gy. With PDR-Brachytherapy: pulsed-dose 0.5–0.8 Gy/pulse, total dose 50 Gy, scheduled every hour, 24 h per day, total treatment time of 4–5 days. Recommended schedules for lumpectomy boost with PDR-BCT: pulsed-dose 0.5–0.8 Gy/pulse, total dose 10–20 Gy, scheduled every hour, 24 h per day, total treatment time 1–2 days.4. Advantages and Disadvantages of the Technique

The effectiveness of brachytherapy is based on the very high radiation dose directly delivered to the target volume by placing radiation sources in close proximity to or inside the tumor mass/tumor bed. A unique characteristic of this technique is the rapid dose fall-off outside the sources at the end of the implant, thus limiting dose exposure to the surrounding normal tissues. Brachytherapy offers dosimetric advantages with very sharp radiation dose gradients compared to conventional external beam radiation (EBRT) techniques. As the source moves at the same time as the target, an additional margin is not necessary to cover the set-up uncertainties due to the organ motion, with a subsequent reduction of the planning treatment volume (PTV) and a smaller amount of healthy tissue receiving high doses, hence a reduction in side effects [20]. As a result, brachytherapy combines optimal tumor-to-normal tissue gradients while minimizing the integral dose to the remaining patient’s body tissue [21,22,23,24][21][22][23][24]. Brachytherapy is preferred in women with large breast sizes and deep tumor masses because the integral dose delivered with electron beams or EBRT is high, with a high risk of unacceptable lung and/or heart dose. Several studies have shown that, from a dosimetric point of view, brachytherapy boost better protects organs at risk (OARs) from medium to high radiation doses in deeply seated lumpectomy beds, compared to EBRT and high-energy electron beams [24]. Actually, brachytherapy is also the radiation technique with the highest level of scientific evidence regarding APBI and APBrI for ipsilateral breast recurrence after curative treatment [25]. Nevertheless, brachytherapy is also burdened with side effects, which may be minor to intense, depending on the delivered dose, the breast tumor site, and the size of the treated volume. Acute reactions (inflammation and irritation at the treatment site) are frequently in view of the very high doses delivered [25,26][25][26]. However, the significant decrease in the irradiated volume compared to other radiation techniques contributes to the good long-term functional outcome reported in the literature, with the potential for lower rates of normal tissue fibrosis (which is one of the mechanisms underlying organ dysfunction) [25,26][25][26]. Moreover, as it is an invasive treatment, there is a not negligible risk of infection and perioperative pain. The high specialization of the technique, requiring a long learning period to acquire the skills to guarantee the correct positioning of the catheters, may be considered the main limitation of brachytherapy. The Breast BCT procedure also requires specialized equipment able to perform the procedure under aseptic conditions, a dedicated operating room to properly handle the implant, and together with dedicated facilities that meet the radiobiological protection criteria. References1. Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 7–33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

2. Fisher, B.; Bauer, M.; Margolese, R.; Poisson, R.; Pylch, Y.; Redmond, C.; Fisher, E.; Wolmark, N.; Deutsch, M.; Montague, E.; et al.

Five-year results of a randomized clinical trial comparing total mastectomy and segmental mastectomy with or without radiation

in the treatment of breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1985, 312, 665–673. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

3. Fisher, B.; Anderson, S.; Bryant, J.; Margolese, R.; Deutch, M.; Fisher, E.R.; Jeong, J.H.;Wolmark, N. Twenty-year follow-up of a

randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast

cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 1233–1241. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

4. Veronesi, U.; Saccozzi, R.; Del Vecchio, M.; Banfi, A.; Clemente, C.; De Lena, M.; Gallus, G.; Greco, M.; Luini, A.; Marubini, E.;

et al. Comparing radical mastectomy with quadrantectomy, axillary dissection, and radiotherapy in patients with small cancers

of the breast. N. Engl. J. Med. 1981, 305, 6–11. [CrossRef]

5. Veronesi, U.; Cascinelli, N.; Mariani, L.; Greco, M.; Saccozzi, R.; Luini, A.; Aguilar, M.; Marubuni, E. Twenty year follow-up of a

randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002,

347, 1227–1232. [CrossRef]

6. Keynes, G. The place of radium in the treatment of cancer of the breast. Ann. Surg. 1937, 106, 619–630. [CrossRef]

7. Polgar, C.; Fodor, J.; Major, T.; Sulyok, Z.; Kásler, M. Breast-conserving therapy with partial or whole breast irradiation: Ten-year

results of the Budapest randomized trial. Radiother. Oncol. 2013, 108, 197–202. [CrossRef]

8. Ott, O.J.; Hildebrandt, G.; Potter, R.; Hammer, J.; Lotter, M.; Resch, A.; Sauer, R.; Strnad, V. Accelerated partial breast irradiation

with multi-catheter brachytherapy: Local control, side effects and cosmetic outcome for 274 patients. Results of the

GermanAustrian multi-centre trial. Radiother. Oncol. 2007, 82, 281–286. [CrossRef]

9. Strnad, V.; Hildebrandt, G.; Pötter, R.; Hammer, J.; Hindemith, M.; Resch, A.; Spiegl, K.; Lotter, M.; Uter, W.; Bani, M.; et al.

Accelerated partial breast irradiation: 5-year results of the German-ustrian multicenter phase II trial using interstitial multicatheter

brachytherapy alone after breast-conserving surgery. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2011, 80, 17–24. [CrossRef]

10. Polgar, C.; Major, T.; Fodor, J.; Sulyok, Z.; Somogyi, A.; Lovey, K.; Nemeth, G.; Klaser, M. Accelerated partial-breast irradiation

using high-dose-rate interstitial brachytherapy: 12-year update of a prospective clinical study. Radiother. Oncol. 2010, 94, 274–279.

[CrossRef]

11. Hannoun-Levi, J.M.; Resch, A.; Gal, J.; Kauer-Dorner, D.; Strnad, V.; Niehoff, P.; Loessl, K.; Kovács, G.; Van Lim-bergen, E.; Polgár,

C.; et al. Accelerated partial breast irradiation with interstitial brachytherapy as second conservative treatment for ipsilateral

breast tumour recurrence: Multicentric study of the GEC-ESTRO Breast Cancer Working Group. Radiother. Oncol. 2013, 108,

226–231. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

12. Pierquin, B.; Wilson, J.-F.; Chassagne, D. The Paris System. In Modern Brachytherapy; Pierquin, B., Wilson, J.F., Chassagne, D., Eds.;

Masson: Paris, France, 1987.

13. Major, T.; Fröhlich, G.; Lövey, K.; Fodor, J.; Polgár, C. Dosimetric experience with accelerated partial breastirradiation using

image-guided interstitial brachytherapy. Radiother. Oncol. 2009, 90, 48–55. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

14. Polgar, C.; Strnad, V.; Major, T. Brachytherapy for partial breast irradiation: The European experience. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 2005,

15, 116–122. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

15. Polgar, C.; Van Limbergen, E.; Potter, R.; Kovacs, G.; Polo, A.; Lyczek, J.; Hildebrandt, G.; Niehoff, P.; Guinot, J.L.; Guedea, F.; et al.

Patient selection for accelerated partial-breast irradiation (APBI) after breastconserving surgery: Recommendations of the Group

Europeen de Curietherapie-European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (GEC-ESTRO) breast cancer working

group based on clinical evidence (2009). Radiother. Oncol. 2010, 94, 264–273. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

16. Strnad, V.; Hannoun-Lévi, J.-M.; Guinot, J.-L.; Lössl, K.; Kauer-Dorner, D.; Resch, A.; Kovacs, G.; Major, T.; Van Limnergen, E.

Recommendations from GEC ESTRO Breast CancerWorking Group (I): Target definition and target delineation for accelerated

or boost partial breast irradiation using multicatheter interstitial brachytherapy after breast conserving closed cavity surgery.

Radiother. Oncol. 2015, 115, 342–348. [CrossRef]

17. Major, T.; Gutiérrez, C.; Guix, B.; van Limbergen, E.; Strnad, V.; Polgar, C. Recommendations from GEC ESTRO Breast Cancer

Working Group (II): Target definition and target delineation for accelerated or boost partial breast irradiation using multicatheter

interstitial brachytherapy after breast conserving open cavity surgery. Radiother. Oncol. 2016, 118, 199–204. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

18. Strnad, V.; Ott, O.J.; Hildebrandt, G.; Kauer-Dorner, D.; Knauerhase, H.; Major, T.; Lyczek, J.; Guinot, J.L.; Dunst, J.; Gutierrez

whole-breast irradiation with boost after breast-conserving surgery for low-risk invasive and in-situ carcinoma of the female

breast: A randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 229–238. [CrossRef]

19. Sato, K.; Shimo, T.; Fuchikami, H.; Takeda, N.; Kato, M.; Okawa, T. Catheter-based delineation of lumpectomy cavity for accurate

target definition in partial-breast irradiation with multicatheter interstitial brachytherapy. J. Contemp. Brachyther. 2019, 11, 108–115.

[CrossRef]

20. Strnad, V.; Major, T.; Polgar, C.; Lotter, M.; Guinot, J.L. ESTRO-ACROP guideline: Interstitial multi-catheter breast brachytherapy

as Accelerated Partial Breast Irradiation alone or as boost—GEC-ESTRO Breast CancerWorking Group practical recommendations.

Radiother. Oncol. 2018, 128, 411–420. [CrossRef]

21. Chargari, C.; Van Limbergen, E.; Mahantshetty, U.; Deutsch, E.; Haie-Meder, C. Radiobiology of brachytherapy: The historical

view based on linear quadratic model and perspectives for optimization. Cancer Radiother. 2018, 22, 312–318. [CrossRef]

22. Georg, D.; Kirisits, C.; Hillbrand, M.; Dimopoulos, J.; Potter, R. Image-guided radiotherapy for cervix cancer: High-tech external

beam therapy versus high-tech brachytherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2008, 71, 1272–1278. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

23. Yanez, L.; Ciudad, A.M.; Mehta, M.P.; Marisglia, H. What is the evidence for the clinical value of SBRT in cancer of the cervix?

Rep. Pract. Oncol. Radiother. 2018, 23, 574–579. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

24. Otahal, B.; Dolezel, M.; Cvek, J.; Simetka, O.; Klat, J.; Knibel, L.; MOlenda, L.; Skacelikova, E.; Hlavka, A.; Felti, D. Dosimetric

comparison of MRI-based HDR brachytherapy and stereotactic radiotherapy in patients with advanced cervical cancer: A virtual

brachytherapy study. Rep. Pract. Oncol. Radiother. 2014, 19, 399–404. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

25. Chargari, C.; Deutsch, E.; Blanchard, P.; Gouy, S.; Martelli, H.; Guerin, F.; Dumas, I.; Bossi, A.; MOrice, P.; Viswanathan, A.; et al.

Brachytherapy: An overview for clinicians. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 386–401. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

26. Sato, K.; Shimo, T.; Fuchikami, H.; Takeda, N.; Kato, M.; Okawa, T. Predicting adherence of dose-volume constraints for

personalized partial-breast irradiation technique. Brachytherapy 2021, 20, 163–170. [CrossRef]

27. Liljegren, G.; Holmberg, L.; Adami, H.O.; Weatman, G.; Graffman, S.; Bergh, J.; Uppsala-Orebro Breast Cancer Study Group.

Sector resection with or without postoperative radiotherapy for stage I breast cancer: Five-year results of a randomized trial. J.

Natl. Cancer Inst. 1994, 86, 717–722. [CrossRef]

28. Veronesi, U.; Marubini, E.; Mariani, L.; Galimberti, V.; Luini, A.; Verosnesi, P.; Zucali, R. Radiotherapy after breast-conserving

surgery in small breast carcinoma: Long-term results of a randomized trial. Ann. Oncol. 2001, 12, 997–1003. [CrossRef]

29. Bartelink, H.; Horiot, J.C.; Poortmans, P.; Struikmans, H.; Van den Bogaert, W.; Batillot, I.; Fourquet, A.; Borger, J.; Jager, J.;

Hoogenraad, L.; et al. Recurrence rates after treatment of breast cancer with standard radio- therapy with or without additional

radiation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 1378–1387. [CrossRef]

30. Polo, A.; Polgár, C.; Hannoun-Lévi, J.-M.; Guinot, J.-L.; Gutierrez, C.; Galalae, R.; VanLimbergen, E.; Strnad, V. Risk factors and

state-of-the-art indications for boost irradiation in invasive breast carcinoma. Brachytherapy 2017, 16, 552–564. [CrossRef]

31. Bartelink, H.; Maingon, P.; Poortmans, P.; Weltens, C.; Fourquet, A.; Jager, J.; Schinagl, D.; Dei, B.; Rodenhuis, C.; Horiot, J.C.;

et al. Whole-breast irradiation with or without a boost for patients treated with breast-conserving surgery for early breast cancer:

20-year follow-up of a ran- domised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 47–56. [CrossRef]

32. Mansfield, C.M.; Komarnicky, L.T.; Schwartz, G.F.; Rosenberg, A.L.; Krishnan, L.; Jewell,W.R.; Rosato, F.E.; Moses, M.L.; Haghbin,

M.; Taylor, J. Ten-year results in 1070 patients with stages I and II breast cancer treated by conservative surgery and radiation

therapy. Cancer 1995, 75, 2328–2336. [CrossRef]

33. Knauerhase, H.; Strietzel, M.; Gerber, B.; Reimer, T.; Fietkau, R. Tumor location, interval between surgery and radiotherapy, and

boost technique influence local control after breast-conserving surgery and radiation: Retrospective analysis of monoinstitutional

long-term results. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2008, 72, 1048–1055. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

34. Polgár, C.; Jánváry, L.; Major, T.; Somogyi, A.; Takácsi-Nagy, Z.; Fröhlich, G.; Fodor, J. The role of high-dose-rate brachytherapy

boost in breast-conserving therapy: Long-term results of the Hungarian National Institute of Oncology. Rep. Pract. Oncol.

Radiother. 2010, 15, 1–7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

35. Poortmans, P.; Bartelink, H.; Horiot, J.C.; Struikmans, H.; Van den Bogaert, W.; Fourquet, A.; Jager, J.; Hoogenraad, W.; Rodrigus,

P.;Wárlám-Rodenhuis, C.; et al. The influence of the boost technique on local control in breast conserving treatment in the EORTC

’boost versus no boost’ randomised trial. Radiother. Oncol. 2004, 72, 25–33. [CrossRef]

36. Quéro, L.; Guillerm, S.; Taright, N.; Michaud, S.; Teixeira, L.; Cahen-Doidy, L.; Bourstyn, E.; Espié, M.; Hennequin, C. 10-Year

follow-up of 621 patients treated using high-dose rate brachytherapy as ambulatory boost technique in conservative breast cancer

treatment. Radiother. Oncol. 2017, 122, 11–16. [CrossRef]

37. Clark, R.M.; McCulloch, P.B.; Levine, M.N.; Lipa, M.;Wilkinson, R.H.; Mahoney, L.J.; Basrur, V.R.; Nair, B.D.; McDermot, R.S.;

Wong, C.S.; et al. Randomized clinical trial to assess the effectiveness of breast irradiation following lumpectomy and axillary

dissection for node-negative breast cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1996, 84, 683–689. [CrossRef]

38. Liljegren, G.; Holmberg, L.; Bergh, J.; Lindgren, A.; Tabar, L.; Nordgren, H.; Adami, H.O. 10-year results after sector resection with

or without postoperative radiotherapy for stage I breast cancer: A randomized trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 1999, 17, 2326–2333. [CrossRef]

39. Fisher, E.R.; Anderson, S.; Redmond, C.; Fisher, B. Psilateral breast tumor recurrence and survival following lumpectomy and

irradiation: Pathologic findings from NSABP protocol B-06. Semin. Surg. Oncol. 1992, 8, 161–166.

40. Wazer, D.E.; Schmidt-Ullrich, R.K.; Ruthazer, R.; Schmid, C.H.; Graham, r.; Safari, H.; Rothschild, J.; McGrath, J.; Erban, J.K.

Factors determing outcome for breast conserving irradiation with margin-directed dose escalation to the tumor bed. Int. J. Radiat.

Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1998, 40, 851–858. [CrossRef]miguelez, C.; et al. 5-year results of accelerated partial breast irradiation using sole interstitial multicatheter brachytherapy versus Galalae, R.; Hannoun-Lévi, J.M. Accelerated partial breast irradiation by brachytherapy: Present evidence and future developments.

Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 50, 743–752. [CrossRef]

42. Correa, C.; Harris, E.E.; Leonardi, M.C.; Smith, B.D.; Taghian, A.G.; Thompson, A.M.; White, J.; Harris, J.R. Accelerated Partial

Breast Irradiation: Executive summary for the update of an ASTRO Evidence-Based Consensus Statement. Pract. Radiat. Oncol.

2017, 7, 73–79. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

43. Shah, C.; Vicini, F.; Shaitelman, S.F.; Hepel, J.; Keisch, M.; Arthur, D.; Khan, A.J.; Kuske, R.; Patel, R.;Wazer, D.E. The American

Brachytherapy Society consensus statement for accelerated partial-breast irradiation. Brachytherapy 2018, 17, 154–170. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

44. Wazer, D.E.; Berle, L.; Graham, R.; Chung, M.; Rothschild, J.; Graves, T.; Cady, B.; Ulin, K.; Ruthazer, R.; DiPetrillo, T.A.

Preliminary results of a phase I/II study of HDR brachytherapy alone for T1/T2 breast cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys.

2002, 53, 889–897. [CrossRef]

45. Perera, F.; Yu, E.; Engel, J.; Holliday, R.; Scott, L.; Chisela, F.; Venkatesan, V. Patterns of breast recurrence in a pilot study of

brachytherapy confined to the lumpectomy site for early breast cancer with six years’ minimum follow-up. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol.

Biol. Phys. 2003, 57, 1239–1246. [CrossRef]

46. Polgár, C.; Major, T.; Fodor, J.; Németh, G.; Orosz, Z.; Sulyok, Z.; Udvarhelyi, N.; Somogyi, A.; Takacsi-Nagy, Z.; Lovey, K.; et al.

High-dose-rate brachytherapy alone versus whole breast radiotherapy with or without tumor bed boost after breast-conserving

surgery: Seven-year results of a comparative study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2004, 60, 1173–1181. [CrossRef]

47. Kaufman, S.A.; DiPetrillo, T.A.; Price, L.L.; Midle, J.B.;Wazer, D.E. Long-term outcome and toxicity in a Phase I/II trial using

high-dose-rate multicatheter interstitial brachytherapy for T1/T2 breast cancer. Brachytherapy 2007, 6, 286–292. [CrossRef]

48. Wallace, M.; Martinez, A.; Mitchell, C.; Chen, P.Y.; Ghilezan, M.; Benitez, P.; Brown, E.; Vicini, F. Phase I/II study evaluating early

tolerance in breast cancer patients undergoing accelerated partial breast irradiation treated with the mammosite balloon breast

brachytherapy catheter using a 2-day dose schedule. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2010, 77, 531–536. [CrossRef]

49. Shah, C.; Badiyan, S.; Wilkinson, J.B.; Vicini, F.; Beitsch, P.; Keisch, M.; Arthur, D.; Lyden, M. Treatment efficacy with accelerated

partial breast irradiation (APBI): Final analysis of the American Society of Breast Surgeons MammoSite® breast brachytherapy

registry trial. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2013, 20, 3279–3285. [CrossRef]

50. Rabinovitch, R.; Winter, K.; Kuske, R.; Bolton, J.; Arthur, D.; Scroggins, T.; Vicini, F.; McCormick, B.; White, J. RTOG 95-17, a Phase

II trial to evaluate brachytherapy as the sole method of radiation therapy for Stage I and II breast carcinoma-year-5 toxicity and

cosmesis. Brachytherapy 2014, 13, 17–22. [CrossRef]

51. White, J.;Winter, K.; Kuske, R.R.; Bolton, J.S.; Arthur, D.W.; Scroggins, T.; Rabinivitch, R.A.; Kelly, T.; Toonkel, L.M.; Vicini, F.A.;

et al. Long-Term Cancer Outcomes From Study NRG Oncology/RTOG 9517: A Phase 2 Study of Accelerated Partial Breast

Irradiation with Multicatheter Brachytherapy after Lumpectomy for Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys.

2016, 95, 1460–1465. [CrossRef]

52. Wobb, J.L.; Shah, C.; Chen, P.Y.; Wallace, M.; Ye, H.; Jawad, M.S.; Grills, I.S. Brachytherapy-based Accelerated Partial Breast

Irradiation Provides Equivalent 10-Year Outcomes to Whole Breast Irradiation: A Matched-Pair Analysis. Am. J. Clin. Oncol.

2016, 39, 468–472. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

53. Cozzi, S.; Laplana, M.; Najjari, D.; Slocker, A.; Encina, X.; Pera, J.; Guedea, F.; Gutierrez, C. Advantages of intraoperative implant

for interstitial brachytherapy for accelerated partial breast irradiation either frail patients with early-stage disease or in locally

recurrent breast cancer. J. Contemp. Brachyther. 2018, 10, 97–104. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

54. Hepel, J.T.; Yashar, C.; Leonard, K.L.; Einck, J.P.; Sha, S.; DiPetrillo, T.; Wiggins, D.; Graves, T.; Edmonson, D.; Wazer, D.

Five fraction accelerated partial breast irradiation using noninvasive image-guided breast brachytherapy: Feasibility and acute

toxicity. Brachytherapy 2018, 17, 825–830. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

55. Pohanková, D.; Sirák, I.; Jandík, P.; Kašaova, L.; Grepl, J.; Motyˇcka, P.; Asqar, A.; Paluska, P.; Ninger, V.; Bydžovská, I.;

et al. Accelerated partial breast irradiation with perioperative multicatheter interstitial brachytherapy—A feasibility study.

Brachytherapy 2018, 17, 949–955. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

56. Khan, A.J.; Chen, P.Y.; Yashar, C.; Poppe, M.M.; Li, L.; Yehia, Z.A.; Vicini, F.A.; Moore, D.; Dale, R.; Arthur, D.; et al. Three-Fraction

Accelerated Partial Breast Irradiation (APBI) Delivered with Brachytherapy Applicators Is Feasible and Safe: First Results from

the TRIUMPH-T Trial. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2019, 104, 67–74. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

57. Vicini, F.A.; Cecchini, R.S.; White, J.R.; Arthur, D.W.; Julian, T.B.; Rabinovitch, R.A.; Kuske, R.; Ganz, P.; Parda, D.S.; Scheier, M.F.;

et al. Long-term primary results of accelerated partial breast irradiation after breast-conserving surgery for early-stage breast

cancer: A randomised, phase 3, equivalence trial. Lancet 2019, 394, 2155–2164. [CrossRef]

58. Mutter, R.W.; Hepel, J.T. Accelerated Partial Breast Radiation: Information on Dose, Volume, Fractionation, and Efficacy from

Randomized Trials. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2020, 108, 1123–1128. [CrossRef]

59. Vicini, F.A.; Cecchini, R.S.; White, J.R.; Julian, T.B.; Arthur, D.W.; Rabinovitch, R.A. Primary results of NSABP B-39/RTOG 0413

(NRG Oncology): A randomized phase III study of conventional whole breast irradiation versus partial breast irradiation for

women with stage 0, I, or II breast cancer. In Proceedings of the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, San Antonio, TX, USA,

4–8 December 2018.

60. Gaudet, M.; Pharand-Charbonneau, M.; Wright, D.; Nguyen, J.; Trudel-Sabourin, J.; Chelfi, M. Long-term results of multicatheter

interstitial high-dose-rate brachytherapy for accelerated partial-breast irradiation. Brachytherapy 2019, 18, 211–216. [CrossRef] Maranzano, E.; Arcidiacono, F.; Italiani, M.; Anselmo, P.; Casale, M.; Terenzi, S.; Di Marzo, A.; Fabiani, S.; Draghini, L.; Trippa, F.

Accelerated partial-breast irradiation with high-dose-rate brachytherapy: Mature results of a Phase II trial. Brachytherapy 2019, 18,

627–634. [CrossRef]

62. Hannoun-Lévi, J.M.; Cham Kee, D.L.; Gal, J.; Schiappa, R.; Hannoun, A.; Gautier, M.; Boulahssass, R.; Peyrottes, I.; Barranger,

E.; Ferrero, J.M.; et al. Accelerated partial breast irradiation for suitable elderly women using a single fraction of multicatheter

interstitial high-dose-rate brachytherapy: Early results of the Single-Fraction Elderly Breast Irradiation (SiFEBI) Phase I/II trial.

Brachytherapy 2018, 17, 407–414. [CrossRef]

63. Hannoun-Lévi, J.M.; Lam Cham Kee, D.; Gal, J.; Schiappa, R.; Hannoun, A.; Fouche, Y.; Gautier, M.; Boulahssass, R.; Chand, M.E.

Accelerated partial breast irradiation in the elderly: 5-Year results of the single fraction elderly breast irradiation (SiFEBI) phase

I/II trial. Brachytherapy 2020, 19, 90–96. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

64. Rodriguez-Ibarria, N.G.; Pinar, M.B.; García, L.; Cabezón, M.A.; Lloret, M.; Rey-Baltar, M.D.; Rdguez-Melcón, J.I.; Lara, P.C.

Accelerated partial breast irradiation with interstitial multicatheter brachytherapy after breast-conserving surgery for low-risk

early breast cancer. Breast 2020, 52, 45–49. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

65. Laplana, M.; Cozzi, S.; Najjari, D.; Martín, M.I.; Rodriguez, G.; Slocker, E.; Sancho, I.; Pla, M.J.; Garcia, M.; Gracia, R.; et al.

Five-year results of accelerated partial breast irradiation: A single-institution retrospective review of 289 cases. Brachytherapy

2021, 20, 807–817. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

66. Hepel, J.T.; Leonard, K.L.; Rivard, M.; Benda, R.; Pittier, A.; Mastras, D.; Sha, S.; Smith, L.; Kerley, M.; Kocheril, P.G.; et al.

Multi-institutional registry study evaluating the feasibility and toxicity of accelerated partial breast irradiation using noninvasive

image-guided breast brachytherapy. Brachytherapy 2021, 20, 631–637. [CrossRef]

67. Polgár, C.; Major, T.; Takácsi-Nagy, Z.; Fodor, J. Breast-Conserving Surgery Followed by Partial or Whole Breast Irradiation:

Twenty-Year Results of a Phase 3 Clinical Study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2021, 109, 998–1006. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

68. Garduño-Sánchez, S.; Villanego-Beltrán, I.; de Las Peñas-Cabrera, M.D.; Jaén-Olasolo, J. Comparison between Accelerated Partial

Breast Irradiation with multicatheter interstitial brachytherapy and Whole Breast Irradiation, in clinical practice. Clin. Transl.

Oncol. 2022, 24, 24–33. [CrossRef]

69. Polgár, C.; Ott, O.J.; Hildebrandt, G.; Kauer-Dorner, D.; Knauerhase, H.; Major, T.; Lyczek, J.; Guinot, J.L.; Dunst, J.; Gutierrez

Miguelez, C.; et al. Late side-effects and cosmetic results of accelerated partial breast irradiation with interstitial brachytherapy

versus whole-breast irradiation after breast-conserving surgery for low-risk invasive and in-situ carcinoma of the female breast:

5-year results of a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 259–268. [CrossRef]

70. Schäfer, R.; Strnad, V.; Polgár, C.; Uter, W.; Hildebrandt, G.; Ott, O.J.; Kauer-Dornes, D.; Knauerhase, H.; Majir, T.; Lyczek, J.; et al.

Quality-of-life results for accelerated partial breast irradiation with interstitial brachytherapy versus whole-breast irradiation in

early breast cancer after breast-conserving surgery (GEC-ESTRO): 5-year results of a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol.

2018, 19, 834–844. [CrossRef]

71. Perrucci, E.; Lancellotta, V.; Bini, V.; Falcinelli, L.; Farneti, A.; Margaritelli, M.; Capezzali, G.; Palumbo, I.; Aristei, C. Quality of life

and cosmesis after breast cancer: Whole breast radiotherapy vs. partial breast high-dose-rate brachytherapy. Tumori 2015, 101,

161–167. [CrossRef]

72. Wadasadawala, T.; Maitre, P.; Sinha, S.; Parmar, V.; Pathak, R.; Gaikar, M.; Verma, S.; Sarin, R. Patient-reported quality of life with

interstitial partial breast brachytherapy and external beam whole breast radiotherapy: A comparison using propensity-score

matching. J. Contemp. Brachyther. 2021, 13, 387–394. [CrossRef]

73. Wobb, J.L.; Shah, C.; Jawad, M.S.; Wallace, M.; Dilworth, J.T.; Grills, I.S.; Ye, H.; Chen, P.Y. Comparison of chronic toxicities

between brachytherapy-based accelerated partial breast irradiation and whole breast irradiation using intensity modulated

radiotherapy. Breast 2015, 24, 739–744. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

74. Fisher, B.; Daugherty, L.; Shaikh, T.; Reiff, J.; Perlingiero, D.; Alite, F.; Brady, L.; Komarnicky, L. Tumor bed-to-skin distance using

accelerated partial-breast irradiation with the strut-adjusted volume implant device. Brachytherapy 2012, 11, 387–391. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

75. Cuttino, L.W.; Arthur, D.W.; Vicini, F.; Todor, D.; Julian, T.; Mukhopadhyay, M. Long-term results from the Contura multilumen

balloon breast brachytherapy catheter phase 4 registry trial. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2014, 90, 1025–1029. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

76. Gentilini, O.; Botteri, E.; Veronesi, P.; Sangalli, C.; Del Castillo, A.; Ballardini, B.; Galimberti, V.; Rietjens, M.; Colleoni, M.; Luini,

A.; et al. Repeating conservative surgery after ipsilateral breast tumor reappearance: Criteria for selecting the best candidates.

Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 19, 3771–3776. [CrossRef]

77. Walstra, C.J.E.F.; Schipper, R.; Poodt, I.G.M.; van Riet, Y.E.; Voogd, A.C.; van der Sangen, M.; Nieuwenhuijzen, G. European

Journal of Surgical Oncology Repeat breast-conserving therapy for ipsilateral breast cancer recurrence: A systematic review. Eur.

J. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 45, 1317–1327. [CrossRef]

78. Hannoun-Levi, J.-M.; Ihrai, T.; Courdi, A. Local treatment options for ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2013,

39, 737–741. [CrossRef]

79. Hannoun Levi, J.M.; van Limbergen, E.; Gal, J.; Chand, M.E.; Schiappa, R.; Smanyko, V.; Kauer-Domer, D.; Pasqiuier, D.; Lemanski,

C.; Racadot, S.; et al. Salvage mastectomy versus second conservative treatment for second ipsilateral breast tumor event: A

Maulard, C.; Housset, M.; Brunel, P.; Delanian, S.; Taurelle, R.; Baillet, F. Use of perioperative or split-course interstitial

brachytherapy techniques for salvage irradiation of isolated local recurrences after conservative management of breast cancer.

Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 1995, 18, 348–352. [CrossRef]

81. Hannoun-Levi, J.M.; Houvenaeghel, G.; Ellis, S.; Teissier, E.; Alzieu, C.; Lallement, M.; Cowen, D. Partial breast irradiation as

second conservative treatment for local breast cancer recurrence. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2004, 60, 1385–1392. [CrossRef]

82. Niehoff, P.; Dietrich, J.; Ostertag, H.; Niehoff, P.; Dietrich, J.; Ostertag, H.; Schmid, A.; Kohr, P.; Kimmig, B.; Kovacs, G. High-doserate

(HDR) or pulsed-doserate (PDR) perioperative interstitial intensity-modulated brachytherapy (IMBT) for local recurrences of

previously irradiated breast or thoracic wall following breast cancer. Strahlenther. Onkol. 2006, 182, 102–107. [CrossRef]

83. Chadha, M.; Feldman, S.; Boolbol, S.; Wang, L.; Harrison, L. The feasibility of a second lumpectomy and breast brachytherapy for

localized cancer in a breast previously treated with lumpectomy and radiation therapy for breast cancer. Brachytherapy 2008, 7,

22–28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

84. Guix, B.; Lejárcegui, J.A.; Tello, J.I.; Zanon, I.; Henriquez, I.; Finestre, F.; Martinez, A.; Ibiza, J.; Quinzanos, L.; Palombo, P.; et al.

Exeresis and brachytherapy as salvage treatment for local recurrence after conservative treatment for breast cancer: Results of a

ten-year pilot study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2010, 78, 804–810. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

85. Hannoun-Levi, J.M.; Castelli, J.; Plesu, A.; Courdi, A.; Raoust, I.; Lallement, M.; Flipo, B.; Ettore, F.; Chapelier, C.; Follana, P.; et al.

Second conservative treatment for ipsilateral breast cancer recurrence using high-dose rate interstitial brachytherapy: Preliminary

clinical results and evaluation of patient satisfaction. Brachytherapy 2011, 10, 171–177. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

86. Kauer-dorner, D.; Pötter, R.; Resch, A.; Handl-Zeller, L.; Kirchheiner, K.; Schell, M.M.; Dorr,W. Partial breast irradiation for locally

recurrent breast cancer within a second breast conserving treatment: Alternative to mastectomy? Results from a prospective trial.

Radiother. Oncol. 2018, 102, 96–101. [CrossRef]

87. Smanykó, V.; Mészáros, N.; Újhelyi, M.; Fröhlich, G.; Stelczer, G.; Major, T.; Mátrai, Z.; Polgár, C. Second breast-conserving

surgery and interstitial brachytherapy vs. salvage mastectomy for the treatment of local recurrences: 5-year results. Brachytherapy

2019, 18, 411–419. [CrossRef]

88. Montagne, L.; Gal, J.; Chand, M.; Schiappa, R.; Falk, A.; Kinj, R.; Gautier, M.; Hannoun-levi, J.M. GEC-ESTRO APBI classification

as a decision-making tool for the management of 2nd ipsilateral breast tumor event. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 176, 149–157.

[CrossRef]

89. Forster, T.; Akbaba, S.; Schmitt, D.; Krug, D.; El Shafie, R.; Oelmann-Avendano, J.; Lindel, K.; Koning, L.; Arians, N.; Bernhardt,

D.; et al. Second breast conserving therapy after ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence—A 10-year experience of re-irradiation. J.

Contemp. Brachyther. 2019, 11, 312–319. [CrossRef]

90. Cozzi, S.; Jamal, D.N.; Slocker, A.; Tejedor, G.A.; Krengli, M.; Guedea, F.; Gutierrez, C. Second breast-conserving therapy with

interstitial brachytherapy (APBI) as a salvage treatment in ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence: A retrospective study of 40 patients.

J. Contemp. Brachyther. 2019, 11, 101–107. [CrossRef]

91. Vavassori, A.; Riva, G.; Cavallo, I.; Spoto, R.; Dicuonzo, S.; Fodor, C.; Come, S.; Cambria, R.; Cattani, F.; Morra, A.; et al.

High-dose-rate Brachytherapy as Adjuvant Local rEirradiation for Salvage Treatment of Recurrent breAst cancer (BALESTRA): A

retrospective mono-institutional study. J. Contemp. Brachyther. 2020, 12, 207–215. [CrossRef]

92. Chatzikonstantinou, G.; Strouthos, I.; Scherf, C.; Kohn, J.; Solbach, C.; Rodel, C.; Tselis, N. Interstitial multicatheter HDRbrachytherapy

as accelerated partial breast irradiation after second breast-conserving surgery for locally recurrent breast cancer. J.

Radiat. Res. 2021, 62, 465–472. [CrossRef]propensity-score matched cohort analysis. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2018, 102, S80. [CrossRef]

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 7–33.

- Fisher, B.; Bauer, M.; Margolese, R.; Poisson, R.; Pylch, Y.; Redmond, C.; Fisher, E.; Wolmark, N.; Deutsch, M.; Montague, E.; et al. Five-year results of a randomized clinical trial comparing total mastectomy and segmental mastectomy with or without radiation in the treatment of breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1985, 312, 665–673.

- Fisher, B.; Anderson, S.; Bryant, J.; Margolese, R.; Deutch, M.; Fisher, E.R.; Jeong, J.H.; Wolmark, N. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 1233–1241.

- Veronesi, U.; Saccozzi, R.; Del Vecchio, M.; Banfi, A.; Clemente, C.; De Lena, M.; Gallus, G.; Greco, M.; Luini, A.; Marubini, E.; et al. Comparing radical mastectomy with quadrantectomy, axillary dissection, and radiotherapy in patients with small cancers of the breast. N. Engl. J. Med. 1981, 305, 6–11.

- Veronesi, U.; Cascinelli, N.; Mariani, L.; Greco, M.; Saccozzi, R.; Luini, A.; Aguilar, M.; Marubuni, E. Twenty year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 1227–1232.

- Keynes, G. The place of radium in the treatment of cancer of the breast. Ann. Surg. 1937, 106, 619–630.

- Polgar, C.; Fodor, J.; Major, T.; Sulyok, Z.; Kásler, M. Breast-conserving therapy with partial or whole breast irradiation: Ten-year results of the Budapest randomized trial. Radiother. Oncol. 2013, 108, 197–202.

- Ott, O.J.; Hildebrandt, G.; Potter, R.; Hammer, J.; Lotter, M.; Resch, A.; Sauer, R.; Strnad, V. Accelerated partial breast irradiation with multi-catheter brachytherapy: Local control, side effects and cosmetic outcome for 274 patients. Results of the GermanAustrian multi-centre trial. Radiother. Oncol. 2007, 82, 281–286.

- Strnad, V.; Hildebrandt, G.; Pötter, R.; Hammer, J.; Hindemith, M.; Resch, A.; Spiegl, K.; Lotter, M.; Uter, W.; Bani, M.; et al. Accelerated partial breast irradiation: 5-year results of the German-ustrian multicenter phase II trial using interstitial multicatheter brachytherapy alone after breast-conserving surgery. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2011, 80, 17–24.

- Polgar, C.; Major, T.; Fodor, J.; Sulyok, Z.; Somogyi, A.; Lovey, K.; Nemeth, G.; Klaser, M. Accelerated partial-breast irradiation using high-dose-rate interstitial brachytherapy: 12-year update of a prospective clinical study. Radiother. Oncol. 2010, 94, 274–279.

- Hannoun-Levi, J.M.; Resch, A.; Gal, J.; Kauer-Dorner, D.; Strnad, V.; Niehoff, P.; Loessl, K.; Kovács, G.; Van Lim-bergen, E.; Polgár, C.; et al. Accelerated partial breast irradiation with interstitial brachytherapy as second conservative treatment for ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence: Multicentric study of the GEC-ESTRO Breast Cancer Working Group. Radiother. Oncol. 2013, 108, 226–231.

- Pierquin, B.; Wilson, J.-F.; Chassagne, D. The Paris System. In Modern Brachytherapy; Pierquin, B., Wilson, J.F., Chassagne, D., Eds.; Masson: Paris, France, 1987.

- Major, T.; Fröhlich, G.; Lövey, K.; Fodor, J.; Polgár, C. Dosimetric experience with accelerated partial breastirradiation using image-guided interstitial brachytherapy. Radiother. Oncol. 2009, 90, 48–55.

- Polgar, C.; Strnad, V.; Major, T. Brachytherapy for partial breast irradiation: The European experience. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 2005, 15, 116–122.

- Polgar, C.; Van Limbergen, E.; Potter, R.; Kovacs, G.; Polo, A.; Lyczek, J.; Hildebrandt, G.; Niehoff, P.; Guinot, J.L.; Guedea, F.; et al. Patient selection for accelerated partial-breast irradiation (APBI) after breastconserving surgery: Recommendations of the Group Europeen de Curietherapie-European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (GEC-ESTRO) breast cancer working group based on clinical evidence (2009). Radiother. Oncol. 2010, 94, 264–273.

- Strnad, V.; Hannoun-Lévi, J.-M.; Guinot, J.-L.; Lössl, K.; Kauer-Dorner, D.; Resch, A.; Kovacs, G.; Major, T.; Van Limnergen, E. Recommendations from GEC ESTRO Breast Cancer Working Group (I): Target definition and target delineation for accelerated or boost partial breast irradiation using multicatheter interstitial brachytherapy after breast conserving closed cavity surgery. Radiother. Oncol. 2015, 115, 342–348.

- Major, T.; Gutiérrez, C.; Guix, B.; van Limbergen, E.; Strnad, V.; Polgar, C. Recommendations from GEC ESTRO Breast Cancer Working Group (II): Target definition and target delineation for accelerated or boost partial breast irradiation using multicatheter interstitial brachytherapy after breast conserving open cavity surgery. Radiother. Oncol. 2016, 118, 199–204.

- Strnad, V.; Ott, O.J.; Hildebrandt, G.; Kauer-Dorner, D.; Knauerhase, H.; Major, T.; Lyczek, J.; Guinot, J.L.; Dunst, J.; Gutierrez miguelez, C.; et al. 5-year results of accelerated partial breast irradiation using sole interstitial multicatheter brachytherapy versus whole-breast irradiation with boost after breast-conserving surgery for low-risk invasive and in-situ carcinoma of the female breast: A randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 229–238.

- Sato, K.; Shimo, T.; Fuchikami, H.; Takeda, N.; Kato, M.; Okawa, T. Catheter-based delineation of lumpectomy cavity for accurate target definition in partial-breast irradiation with multicatheter interstitial brachytherapy. J. Contemp. Brachyther. 2019, 11, 108–115.

- Strnad, V.; Major, T.; Polgar, C.; Lotter, M.; Guinot, J.L. ESTRO-ACROP guideline: Interstitial multi-catheter breast brachytherapy as Accelerated Partial Breast Irradiation alone or as boost—GEC-ESTRO Breast Cancer Working Group practical recommendations. Radiother. Oncol. 2018, 128, 411–420.

- Chargari, C.; Van Limbergen, E.; Mahantshetty, U.; Deutsch, E.; Haie-Meder, C. Radiobiology of brachytherapy: The historical view based on linear quadratic model and perspectives for optimization. Cancer Radiother. 2018, 22, 312–318.

- Georg, D.; Kirisits, C.; Hillbrand, M.; Dimopoulos, J.; Potter, R. Image-guided radiotherapy for cervix cancer: High-tech external beam therapy versus high-tech brachytherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2008, 71, 1272–1278.

- Yanez, L.; Ciudad, A.M.; Mehta, M.P.; Marisglia, H. What is the evidence for the clinical value of SBRT in cancer of the cervix? Rep. Pract. Oncol. Radiother. 2018, 23, 574–579.

- Otahal, B.; Dolezel, M.; Cvek, J.; Simetka, O.; Klat, J.; Knibel, L.; MOlenda, L.; Skacelikova, E.; Hlavka, A.; Felti, D. Dosimetric comparison of MRI-based HDR brachytherapy and stereotactic radiotherapy in patients with advanced cervical cancer: A virtual brachytherapy study. Rep. Pract. Oncol. Radiother. 2014, 19, 399–404.

- Chargari, C.; Deutsch, E.; Blanchard, P.; Gouy, S.; Martelli, H.; Guerin, F.; Dumas, I.; Bossi, A.; MOrice, P.; Viswanathan, A.; et al. Brachytherapy: An overview for clinicians. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 386–401.

- Sato, K.; Shimo, T.; Fuchikami, H.; Takeda, N.; Kato, M.; Okawa, T. Predicting adherence of dose-volume constraints for personalized partial-breast irradiation technique. Brachytherapy 2021, 20, 163–170.