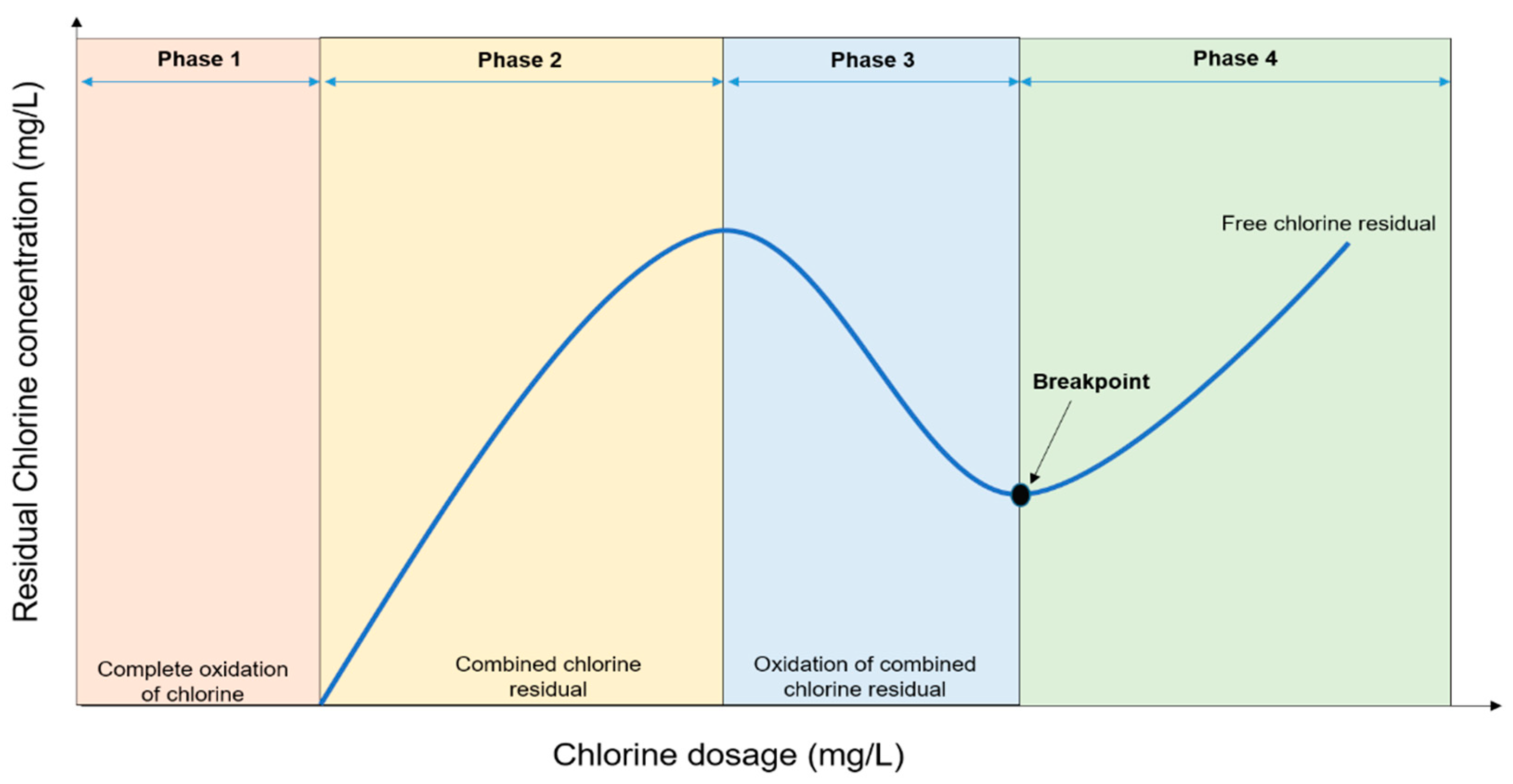

Chlorine first reacts with organic and inorganic matters before pathogens inactivation. The amount of chlorine consumed in this process is termed chlorine demand. The combined chlorine that forms together with any free available chlorine in the water is called the chlorine residual. This is the component of the added chlorine that disinfects the water. Free available chlorine is formed by differences in the concentrations of hypochlorous and hypochlorite ions, a process that depends on the pH of the water. Even though the chlorination procedure is well-researched, establishing an appropriate chlorine dose remains a difficult task for many field applications. Nevertheless, the effective chlorine dose should be sufficient to destroy pathogens and oxidize the organic contaminants as well as maintain sufficient free available chlorine in the water distribution system, post-chlorination.

- waterborne pathogens

- antimicrobial resistance (AMR)

- chlorination

- mutant selection window (MSW)

1. Breakpoint Chlorination and Factors Influencing Disinfection

2. Mechanisms of Chlorine Disinfection

3. Incidences of Chlorine Tolerant Microorganisms from Treated Water Sources

| Source | Microorganism | Disinfectant Concentration/Time | Mechanism(s) of Resistance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drinking water | P. aeruginosa | ≤0.5 mg/L Cl− | Natural resistance due to the permeability barrier caused by outer membrane lipopolysaccharides; biofilm formation | [41][22] |

| Experimental isolates | Acinetobacter baumannii |

0.2–4 mg/L | Increased expression of efflux pumps other antibiotic resistance genes | [42][23] |

| Drinking water reservoir | Acinetobater species, Serratia species | 2 mg/L | Not determined | [35][15] |

| Sewage | Bacillus species | 0.1 mg/L NaOCl | Probable spore formation | [43][24] |

| Secondary effluent | Citrobacter species | 0.5 mg/L Ca(OCl)2 for 30 min | Not determined | [44][25] |

| Drinking water | Bacillus species, Actinomycete | 10 mg/L NaOCl for 2 min | Cellular aggregation or adhesion to suspended particulate. Production of extracellular slime or capsular material | [45][26] |

| Drinking water and experimental isolates | Heterotrophic bacteria, faecal coliforms, E. coli, Salmonella typhimurium, Yersinia enterocolitica, Shigella sonnie | 2.0 mg/L free chlorine for 1 h | Bacterial attachment to surface and production of extracellular slime layer | [46][27] |

| Chlorine-demand–free buffer solution | Coliform isolated from drinking water systems and Enteric bacterial from culture collections cocultured with protozoa (Ciliates and amoebae). | 2–4 mg/L free chlorine for 1–2 h | Shielding of bacteria from chlorine by ingesting protozoans (cysts) and, thus, enhancing resistance | [47][28] |

| Treated drinking water | S. aureus, Micrococcus varians, Aeromonas hydrophila | 1–100 mg/L Ca(OCl)2 solution for 30 min | Possible synthesis of unique proteins or aggregation of bacteria or encapsulation | [33][13] |

| Environmental isolates (Wastewater clarifier effluent) suspended in phosphate buffer saline | Enterococcus species | 0.5 mg/L Ca(OCl)2 for 30 min | Not determined | [48][29] |

| Environmental strains cultured in sterile phosphate buffer solution | Legionella pneumophila from environmental water cocultured with Acanthamoeba species | 2–3 mg/L Cl2 for 1 h with a residual Cl2 of 1 mg/L after 1 h | Possible phenotypic modification of Legionella pneumophila due to intra-cellular growth with Acanthamoeba sp. | [49][30] |

| Environmental isolates from wastewater treatment plants suspended in saline | Bacillus species, Citrobacter freundii, Enterobacter species, Kluyvera cryocrescens, Kluyvera intermedia | 0.5 mg/L NaOCl for 30 min | Authors suggested the possible expression of certain stress factor genes which may reduce bacterial metabolism or change the permeability of cell membranes | [50][31] |

| Environmental isolates (Wastewater clarifier effluent) suspended in phosphate buffer saline | E. coli | 0.5 mg/L NaOCl for 30 min | Not determined | [34][14] |

References

- Musz-Pomorska, A.; Widomski, M.K. Variant analysis of the chlorination efficiency of water in a selected water supply network. Proc. ECOpole 2020, 14, 19–28.

- Jin, M.; Liu, L.; Wang, D.N.; Yang, D.; Liu, W.L.; Yin, J.; Yang, Z.W.; Wang, H.R.; Qiu, Z.G.; Shen, Z.Q.; et al. Chlorine disinfection promotes the exchange of antibiotic resistance genes across bacterial genera by natural transformation. ISME J. 2020, 114, 1847–1856.

- Calomiris, J.; Christman, K. How Does Chlorine Added to Drinking Water Kill Bacteria and Other Harmful Organisms? Why Doesn’t It Harm Us? Scientific American. Available online: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-does-chlorine-added-t/ (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Venkobachar, C.; Iyengar, L.; Rao, A.P. Mechanism of disinfection: Effect of chlorine on cell membrane functions. Water Res. 1977, 11, 727–729.

- Haas, C.N. Mechanisms of Inactivation of New Indicators of Disinfection Efficiency by Free Available Chlorine. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Civil Engineering, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, IL, USA, 1978; p. 158.

- Chang, S.L. Modern concept of disinfection. JSEDA 1971, 97, 689–707.

- Mizozoe, M.; Otaki, M.; Aikawa, K. The mechanism of chlorine damage using enhanced green fluorescent protein-expressing Escherichia coli. Water 2019, 11, 2156.

- Bridges, D.F.; Lacombe, A.; Wu, V.C. Integrity of the Escherichia coli O157: H7 cell wall and membranes after chlorine dioxide treatment. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 888.

- Reed, B.; Shaw, R.; Chatterton, K. Technical Notes on Drinking-Water, Sanitation and Hygiene in Emergencies; WHO, Water, Engineering and Development Centre: Loughborough, UK, 2013.

- Adefisoye, M.A.; Okoh, A.I. Ecological and public health implications of the discharge of multidrug-resistant bacteria and physicochemical contaminants from treated wastewater effluents in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Water 2017, 9, 562.

- National Water Act. Revision of General Authorization in Terms of Section 39 of the National Water Act, 1998 (Act No. 36 of 1998) (The Act); Gazette No. 19182, Notice No. 1091; National Water Act: 1998; South African Government Gazette: Pretoria, South Africa, 1998; Volume 26187.

- Yang, L.; Chen, X.; She, Q.; Cao, G.; Liu, Y.; Chang, V.W.C.; Tang, C.Y. Regulation, formation, exposure, and treatment of disinfection by-products (DBPs) in swimming pool waters: A critical review. Environ. Int. 2018, 121, 1039–1057.

- Al-Berfkani, M.I.; Zubair, A.I.; Bayazed, H. Assessment of chlorine resistant bacteria and their susceptibility to antibiotic from water distribution system in Duhok province. J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol. 2014, 2, 010–013.

- Owoseni, M.C.; Olaniran, A.O.; Okoh, A.I. Chlorine tolerance and inactivation of Escherichia coli recovered from wastewater treatment plants in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 810.

- Jathar, S.; Shinde, D.; Dakhni, S.; Fernandes, A.; Jha, P.; Desai, N.; Jobby, R. Identification and characterization of chlorine-resistant bacteria from water distribution sites of Mumbai. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 5241–5248.

- Martin, D.J.; Wesgate, R.L.; Denyer, S.P.; McDonnell, G.; Maillard, J.Y. Bacillus subtilis vegetative isolate surviving chlorine dioxide exposure: An elusive mechanism of resistance. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 119, 1541–1551.

- Momba, M.N.B.; Kfir, R.; Venter, S.N.; Cloete, T.E. An overview of biofilm formation in distribution systems and its impact on the deterioration of water quality. Water SA 2000, 26, 59–66.

- Bridier, A.; Briandet, R.; Thomas, V.; Dubois-Brissonnet, F. Resistance of bacterial biofilms to disinfectants: A review. Biofouling 2011, 27, 1017–1032.

- Khan, S.; Beattie, T.K.; Knapp, C.W. Relationship between antibiotic-and disinfectant-resistance profiles in bacteria harvested from tap water. Chemosphere 2016, 152, 132–141.

- Du, Z.; Nandakumar, R.; Nickerson, K.W.; Li, X. Proteomic adaptations to starvation prepare Escherichia coli for disinfection tolerance. Water Res. 2015, 69, 110–119.

- Falkinham, J.O.; Pruden, A.; Edwards, M. Opportunistic premise plumbing pathogens: Increasingly important pathogens in drinking water. Pathogens 2015, 4, 373–386.

- Shrivastava, R.; Upreti, R.K.; Jain, S.R.; Prasad, K.N.; Seth, P.K.; Chaturvedi, U.C. Suboptimal chlorine treatment of drinking water leads to selection of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2004, 58, 277–283.

- Karumathil, D.P.; Yin, H.B.; Kollanoor-Johny, A.; Venkitanarayanan, K. Effect of chlorine exposure on the survival and antibiotic gene expression of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in water. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 1844–1854.

- Martins, S.C.S.; Júnior, G.D.S.F.; de Melo Machado, B.; Martins, C.M. Chlorine and antibiotic-resistant bacilli isolated from an effluent treatment plant. Acta Sci. Technol. 2013, 35, 3–9.

- Owoseni, M.; Okoh, A. Assessment of chlorine tolerance profile of Citrobacter species recovered from wastewater treatment plants in Eastern Cape, South Africa. EMA 2017, 189, 201.

- Ridgway, H.F.; Olson, B.H. Chlorine resistance patterns of bacteria from two drinking water distribution systems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1982, 44, 972–987.

- LeChevallier, M.W.; Hassenauer, T.S.; Camper, A.K.; McFETERS, G.A. Disinfection of bacteria attached to granular activated carbon. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1984, 48, 918–923.

- King, C.H.; Shotts, E.B.; Wooley, R.E.; Porter, K.G. Survival of coliforms and bacterial pathogens within protozoa during chlorination. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1988, 54, 3023–3033.

- Owoseni, M.; Okoh, A. Evidence of emerging challenge of chlorine tolerance of Enterococcus species recovered from wastewater treatment plants. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2017, 120, 216–223.

- Dupuy, M.; Mazoua, S.; Berne, F.; Bodet, C.; Garrec, N.; Herbelin, P.; Ménard-Szczebara, F.; Oberti, S.; Rodier, M.H.; Soreau, S.; et al. Efficiency of water disinfectants against Legionella pneumophila and Acanthamoeba. Water Res. 2011, 45, 1087–1094.

- Martínez-Hernández, S.; Vázquez-Rodríguez, G.A.; Beltrán-Hernández, R.I.; Prieto-García, F.; Miranda-López, J.M.; Franco-Abuín, C.M.; Álvarez-Hernández, A.; Iturbe, U.; Coronel-Olivares, C. Resistance and inactivation kinetics of bacterial strains isolated from the non-chlorinated and chlorinated effluents of a WWTP. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 3363–3383.