The Golgi apparatus is at the center of protein processing and trafficking in normal cells. Under pathological conditions, such as in cancer, aberrant Golgi dynamics alter the tumor microenvironment and the immune landscape, which enhances the invasive and metastatic potential of cancer cells. Among these changes in the Golgi in cancer include altered Golgi orientation and morphology that contribute to atypical Golgi function in protein trafficking, post-translational modification, and exocytosis. Golgi-associated gene mutations are ubiquitous across most cancers and are responsible for modifying Golgi function to become pro-metastatic. The pharmacological targeting of the Golgi or its associated genes has been difficult in the clinic; thus, studying the Golgi and its role in cancer is critical to developing novel therapeutic agents that limit cancer progression and metastasis.

- Golgi

- secretion

- cancer secretome

- Metastasis

- Therapeutics and biomarkers

1. Golgi-Mediated Vesicular Trafficking and Exocytosis

2. Golgi Orientation Governs Cell Polarity and Directional Migration

3. Morphology of the Golgi Apparatus

References

- Goldenring, J.R. A central role for vesicle trafficking in epithelial neoplasia: Intracellular highways to carcinogenesis. Nat. Reviews. Cancer 2013, 13, 813–820.

- Bhuin, T.; Roy, J.K. Rab proteins: The key regulators of intracellular vesicle transport. Exp. Cell Res. 2014, 328, 1–19.

- Mughees, M.; Chugh, H.; Wajid, S. Vesicular trafficking-related proteins as the potential therapeutic target for breast cancer. Protoplasma 2020, 257, 345–352.

- Tzeng, H.-T.; Wang, Y.-C. Rab-mediated vesicle trafficking in cancer. J. Biomed. Sci. 2016, 23, 70.

- Acob, A.; Jing, J.; Lee, J.; Schedin, P.; Gilbert, S.M.; Peden, A.A.; Junutula, J.R.; Prekeris, R. Rab40b regulates trafficking of MMP2 and MMP9 during invadopodia formation and invasion of breast cancer cells. J. Cell Sci. 2013, 126 Pt 20, 4647–4658.

- Hendrix, A.; Maynard, D.; Pauwels, P.; Braems, G.; Denys, H.; Van den Broecke, R.; Lambert, J.; Van Belle, S.; Cocquyt, V.; Gespach, C.; et al. Effect of the secretory small GTPase Rab27B on breast cancer growth, invasion, and metastasis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2010, 102, 866–880.

- Lapierre, L.A.; Kumar, R.; Hales, C.M.; Navarre, J.; Bhartur, S.G.; Burnette, J.O.; Provance, D.W., Jr.; Mercer, J.A.; Bähler, M.; Goldenring, J.R. Myosin vb is associated with plasma membrane recycling systems. Mol. Biol. Cell 2001, 12, 1843–1857.

- Welz, T.; Kerkhoff, E. Exploring the iceberg: Prospects of coordinated myosin V and actin assembly functions in transport processes. Small GTPases 2019, 10, 111–121.

- Howe, E.N.; Burnette, M.D.; Justice, M.E.; Schnepp, P.M.; Hedrick, V.; Clancy, J.W.; Guldner, I.H.; Lamere, A.T.; Li, J.; Aryal, U.K.; et al. Rab11b-mediated integrin recycling promotes brain metastatic adaptation and outgrowth. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3017.

- Ferro, E.; Bosia, C.; Campa, C.C. RAB11-mediated trafficking and human cancers: An updated review. Biology 2020, 10, 26.

- Miserey-Lenkei, S.; Bousquet, H.; Pylypenko, O.; Bardin, S.; Dimitrov, A.; Bressanelli, G.; Bonifay, R.; Fraisier, V.; Guillou, C.; Bougeret, C.; et al. Coupling fission and exit of RAB6 vesicles at Golgi hotspots through kinesin-myosin interactions. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1254.

- Ioannou, M.S.; McPherson, P.S. Regulation of Cancer Cell Behavior by the Small GTPase Rab13. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 9929–9937.

- Neary, C.L.; Nesterova, M.; Cho, Y.S.; Cheadle, C.; Becker, K.G.; Cho-Chung, Y.S. Protein kinase A isozyme switching: Eliciting differential cAMP signaling and tumor reversion. Oncogene 2004, 23, 8847–8856.

- Casalou, C.; Faustino, A.; Barral, D.C. Arf proteins in cancer cell migration. Small GTPases 2016, 7, 270–282.

- Casalou, C.; Ferreira, A.; Barral, D.C. The Role of ARF Family Proteins and Their Regulators and Effectors in Cancer Progression: A Therapeutic Perspective. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 217.

- Schlienger, S.; Campbell, S.; Claing, A. ARF1 regulates the Rho/MLC pathway to control EGF-dependent breast cancer cell invasion. Mol. Biol. Cell 2014, 25, 17–29.

- Xie, X.; Tang, S.; Cai, Y.; Pi, W.; Deng, L.; Wu, G.; Chavanieu, A.; Teng, Y. Suppression of breast cancer metastasis through the inactivation of ADP-ribosylation factor 1. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 58111–58120.

- Howley, B.V.; Link, L.A.; Grelet, S.; El-Sabban, M.; Howe, P.H. A CREB3-regulated ER-Golgi trafficking signature promotes metastatic progression in breast cancer. Oncogene 2018, 37, 1308–1325.

- Howley, B.V.; Howe, P.H. Metastasis-associated upregulation of ER-Golgi trafficking kinetics: Regulation of cancer progression via the Golgi apparatus. Oncoscience 2018, 5, 142–143.

- Ruggiero, C.; Grossi, M.; Fragassi, G.; Di Campli, A.; Di Ilio, C.; Luini, A.; Sallese, M. The KDEL receptor signalling cascade targets focal adhesion kinase on focal adhesions and invadopodia. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 10228–10246.

- Bajaj, R.; Kundu, S.T.; Grzeskowiak, C.L.; Fradette, J.J.; Scott, K.L.; Creighton, C.J.; Gibbons, D.L. IMPAD1 and KDELR2 drive invasion and metastasis by enhancing Golgi-mediated secretion. Oncogene 2020, 39, 5979–5994.

- Malsam, J.; Söllner, T.H. Organization of SNAREs within the Golgi stack. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, a005249.

- Sehgal, P.B.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Xu, F.; Patel, K.; Shah, M. Dysfunction of Golgi tethers, SNAREs, and SNAPs in monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2007, 292, L1526–L1542.

- Miyagawa, T.; Hasegawa, K.; Aoki, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Otagiri, Y.; Arasaki, K.; Wakana, Y.; Asano, K.; Tanaka, M.; Yamaguchi, H.; et al. MT1-MMP recruits the ER-Golgi SNARE Bet1 for efficient MT1-MMP transport to the plasma membrane. Cancer Cell Biol. 2019, 218, 3355–3371.

- Steffen, A.; Le Dez, G.; Poincloux, R.; Recchi, C.; Nassoy, P.; Rottner, K.; Galli, T.; Chavrier, P. MT1-MMP-Dependent Invasion Is Regulated by TI-VAMP/VAMP7. Curr. Biol. 2008, 18, 926–931.

- Meng, J.; Wang, J. Role of SNARE proteins in tumourigenesis and their potential as targets for novel anti-cancer therapeutics. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA) Rev. Cancer 2015, 1856, 1–12.

- Peak, T.C.; Su, Y.; Chapple, A.G.; Chyr, J.; Deep, G. Syntaxin 6: A novel predictive and prognostic biomarker in papillary renal cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3146.

- Du, Y.; Shen, J.; Hsu, J.L.; Han, Z.; Hsu, M.C.; Yang, C.C.; Kuo, H.P.; Wang, Y.N.; Yamaguchi, H.; Miller, S.A.; et al. Syntaxin 6-mediated Golgi translocation plays an important role in nuclear functions of EGFR through microtubule-dependent trafficking. Oncogene 2014, 33, 756–770.

- Moreno-Smith, M.; Halder, J.B.; Meltzer, P.S.; Gonda, T.A.; Mangala, L.S.; Rupaimoole, R.; Lu, C.; Nagaraja, A.S.; Gharpure, K.M.; Kang, Y.; et al. ATP11B mediates platinum resistance in ovarian cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 2119–2130.

- Boddul, S.V.; Meng, J.; Dolly, J.O.; Wang, J. SNAP-23 and VAMP-3 contribute to the release of IL-6 and TNFα from a human synovial sarcoma cell line. FEBS J. 2014, 281, 750–765.

- Wang, L.; Brautigan, D.L. α-SNAP inhibits AMPK signaling to reduce mitochondrial biogenesis and dephosphorylates Thr172 in AMPKα in vitro. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1559.

- Naydenov, N.G.; Brown, B.; Harris, G.; Dohn, M.R.; Morales, V.M.; Baranwal, S.; Reynolds, A.B.; Ivanov, A.I. A membrane fusion protein αSNAP is a novel regulator of epithelial apical junctions. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34320.

- Song, J.W.; Zhu, J.; Wu, X.X.; Tu, T.; Huang, J.Q.; Chen, G.Z.; Liang, L.Y.; Zhou, C.H.; Xu, X.; Gong, L.Y. GOLPH3/CKAP4 promotes metastasis and tumorigenicity by enhancing the secretion of exosomal WNT3A in non-small-cell lung cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 976.

- Ravichandran, Y.; Goud, B.; Manneville, J.B. The Golgi apparatus and cell polarity: Roles of the cytoskeleton, the Golgi matrix, and Golgi membranes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2020, 62, 104–113.

- Rizzo, R.; Russo, D.; Kurokawa, K.; Sahu, P.; Lombardi, B.; Supino, D.; Zhukovsky, M.A.; Vocat, A.; Pothukuchi, P.; Kunnathully, V.; et al. Golgi maturation-dependent glycoenzyme recycling controls glycosphingolipid biosynthesis and cell growth via GOLPH3. EMBO J. 2021, 40, e107238.

- Kellokumpu, S. Golgi pH, Ion and Redox Homeostasis: How Much Do They Really Matter? Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 93.

- Mennerich, D.; Kellokumpu, S.; Kietzmann, T. Hypoxia and Reactive Oxygen Species as Modulators of Endoplasmic Reticulum and Golgi Homeostasis. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2019, 30, 113–137.

- Rankin, E.B.; Nam, J.M.; Giaccia, A.J. Hypoxia: Signaling the Metastatic Cascade. Trends Cancer 2016, 2, 295–304.

- Arsenault, D.; Lucien, F.; Dubois, C.M. Hypoxia enhances cancer cell invasion through relocalization of the proprotein convertase furin from the trans-Golgi network to the cell surface. J. Cell. Physiol. 2012, 227, 789–800.

- Bensellam, M.; Maxwell, E.L.; Chan, J.Y.; Luzuriaga, J.; West, P.K.; Jonas, J.-C.; Gunton, J.E.; Laybutt, D.R. Hypoxia reduces ER-to-Golgi protein trafficking and increases cell death by inhibiting the adaptive unfolded protein response in mouse beta cells. Diabetologia 2016, 59, 1492–1502.

- Cheng, H.; Wang, L.; Mollica, M.; Re, A.T.; Wu, S.; Zuo, L. Nitric oxide in cancer metastasis. Cancer lett. 2014, 353, 1–7.

- Iwakiri, Y.; Satoh, A.; Chatterjee, S.; Toomre, D.K.; Chalouni, C.M.; Fulton, D.; Groszmann, R.J.; Shah, V.H.; Sessa, W.C. Nitric oxide synthase generates nitric oxide locally to regulate compartmentalized protein S-nitrosylation and protein trafficking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 19777–19782.

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674.

- Wilson, B.J.; Allen, J.L.; Caswell, P.T. Vesicle trafficking pathways that direct cell migration in 3D matrices and in vivo. Traffic 2018, 19, 899–909.

- Kupfer, A.; Louvard, D.; Singer, S.J. Polarization of the Golgi apparatus and the microtubule-organizing center in cultured fibroblasts at the edge of an experimental wound. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1982, 79, 2603–2607.

- Mu, G.; Ding, Q.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; He, K.; Wu, L.; Deng, Y.; Yang, D.; Wu, L.; et al. Gastrin stimulates pancreatic cancer cell directional migration by activating the Gz12/13-RhoA-ROCK signaling pathway. Exp. Mol. Med. 2018, 50, 1–14.

- Zhang, S.; Schafer-Hales, K.; Khuri, F.R.; Zhou, W.; Vertino, P.M.; Marcus, A.I. The tumor suppressor LKB1 regulates lung cancer cell polarity by mediating cdc42 recruitment and activity. Cell Tumor Stem. Cell Biol. 2008, 68, 740–748.

- Xing, M.; Peterman, M.C.; Davis, R.L.; Oegema, K.; Shiau, A.K.; Field, S.J. GOLPH3 drives cell migration by promoting Golgi reorientation and directional trafficking to the leading edge. Mol. Biol. Cell 2016, 27, 3828–3840.

- Baschieri, F.; Confalonieri, S.; Bertalot, G.; Di Fiore, P.P.; Dietmaier, W.; Leist, M.; Crespo, P.; Macara, I.G.; Farhan, H. Spatial control of Cdc42 signalling by a GM130-RasGRF complex regulates polarity and tumorigenesis. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4839.

- Baschieri, F.; Farhan, H. Endomembrane control of cell polarity: Relevance to cancer. Small GTPases 2015, 6, 104–107.

- Baschieri, F.; Uetz-von Allmen, E.; Legler, D.F.; Farhan, H. Loss of GM130 in breast cancer cells and its effects on cell migration, invasion and polarity. Cell Cycle 2015, 14, 1139–1147.

- Dubois, F.; Alpha, K.; Turner, C.E. Paxillin regulates cell polarization and anterograde vesicle trafficking during cell migration. Mol. Biol. Cell 2017, 28, 3815–3831.

- Mousson, A.; Legrand, M.; Steffan, T.; Vauchelles, R.; Carl, P.; Gies, J.P.; Lehmann, M.; Zuber, G.; De Mey, J.; Dujardin, D.; et al. Inhibiting FAK-Paxillin Interaction Reduces Migration and Invadopodia-Mediated Matrix Degradation in Metastatic Melanoma Cells. Cancers 2021, 13, 1871.

- Yadav, S.; Puri, S.; Linstedt, A.D. A primary role for Golgi positioning in directed secretion, cell polarity and wound healing. Mol. Biol. Cell 2009, 20, 1728–1736.

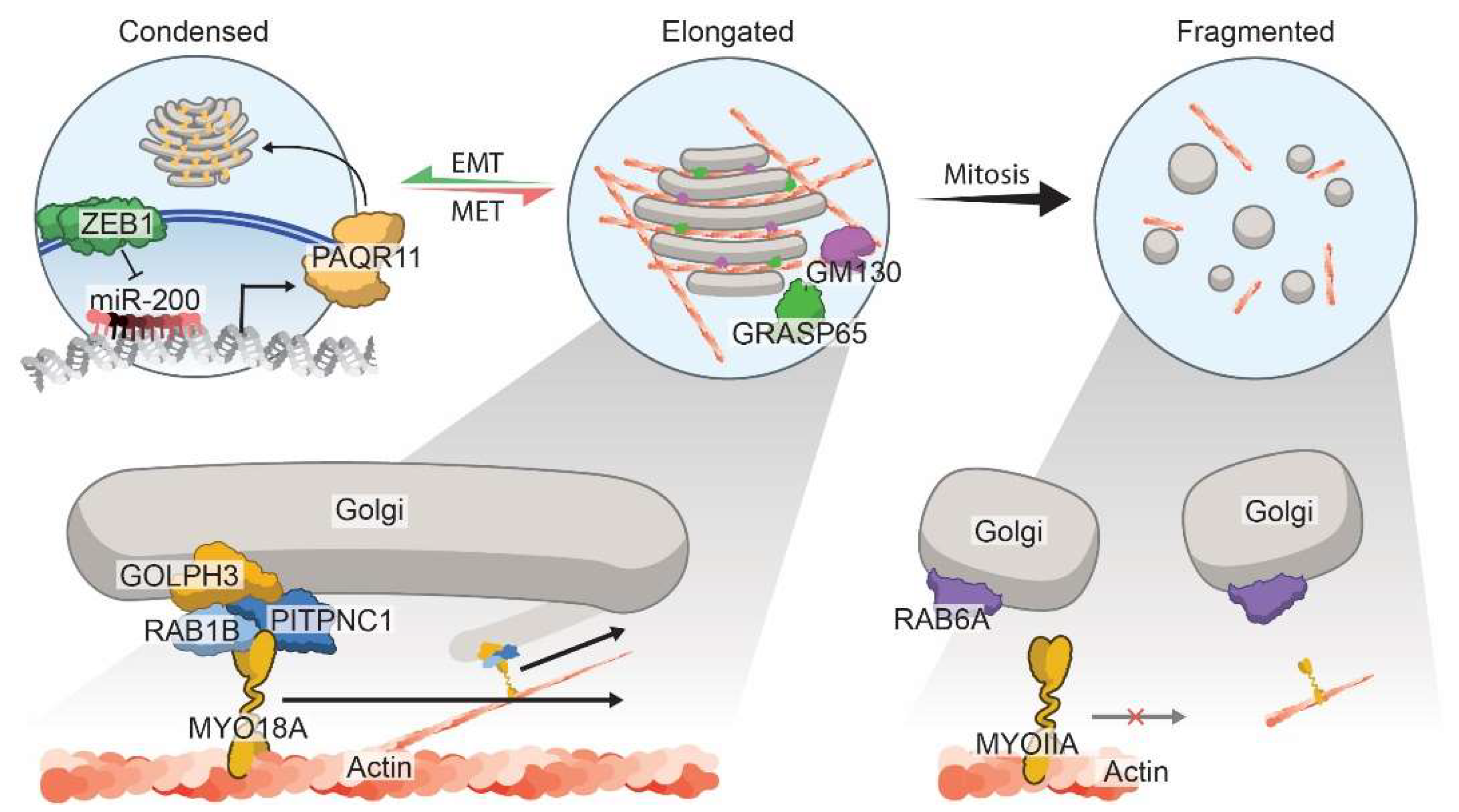

- Tan, X.; Banerjee, P.; Guo, H.F.; Ireland, S.; Pankova, D.; Ahn, Y.H.; Nikolaidis, I.M.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Xue, Y.; et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition drives a pro-metastatic Golgi compaction process through scaffolding protein PAQR11. J. Clin. investig. 2017, 127, 117–131.

- Kalluri, R.; Weinberg, R.A. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 1420–1428.

- Peng, D.H.; Ungewiss, C.; Tong, P.; Byers, L.A.; Wang, J.; Canales, J.R.; Villalobos, P.A.; Uraoka, N.; Mino, B.; Behrens, C.; et al. ZEB1 induces LOXL2-mediated collagen stabilization and deposition in the extracellular matrix to drive lung cancer invasion and metastasis. Oncogene 2017, 36, 1925–1938.

- Gibbons, D.L.; Lin, W.; Creighton, C.J.; Rizvi, Z.H.; Gregory, P.A.; Goodall, G.J.; Thilaganathan, N.; Du, L.; Zhang, Y.; Pertsemlidis, A.; et al. Contextual extracellular cues promote tumor cell EMT and metastasis by regulating miR-200 family expression. Genes Dev. 2009, 23, 2140–2151.

- Gregory, P.A.; Bert, A.G.; Paterson, E.L.; Barry, S.C.; Tsykin, A.; Farshid, G.; Vadas, M.A.; Khew-Goodall, Y.; Goodall, G.J. The miR-200 family and miR-205 regulate epithelial to mesenchymal transition by targeting ZEB1 and SIP1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008, 10, 593–601.

- Ungewiss, C.; Rizvi, Z.H.; Roybal, J.D.; Peng, D.H.; Gold, K.A.; Shin, D.-H.; Creighton, C.J.; Gibbons, D.L. The microRNA-200/Zeb1 axis regulates ECM-dependent β1-integrin/FAK signaling, cancer cell invasion and metastasis through CRKL. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 18652.

- Guo, H.-F.; Bota-Rabassedas, N.; Terajima, M.; Leticia Rodriguez, B.; Gibbons, D.L.; Chen, Y.; Banerjee, P.; Tsai, C.-L.; Tan, X.; Liu, X.; et al. A collagen glucosyltransferase drives lung adenocarcinoma progression in mice. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 482.

- Peng, D.H.; Rodriguez, B.L.; Diao, L.; Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Byers, L.A.; Wei, Y.; Chapman, H.A.; Yamauchi, M.; Behrens, C.; et al. Collagen promotes anti-PD-1/PD-L1 resistance in cancer through LAIR1-dependent CD8(+) T cell exhaustion. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4520.

- Sechi, S.; Frappaolo, A.; Karimpour-Ghahnavieh, A.; Piergentili, R.; Giansanti, M.G. Oncogenic Roles of GOLPH3 in the Physiopathology of Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 933.

- Rahajeng, J.; Kuna, R.S.; Makowski, S.L.; Tran, T.T.T.; Buschman, M.D.; Li, S.; Cheng, N.; Ng, M.M.; Field, S.J. Efficient Golgi Forward Trafficking Requires GOLPH3-Driven, PI4P-Dependent Membrane Curvature. Dev. Cell 2019, 50, 573–585.e575.

- Scott, K.L.; Kabbarah, O.; Liang, M.C.; Ivanova, E.; Anagnostou, V.; Wu, J.; Dhakal, S.; Wu, M.; Chen, S.; Feinberg, T.; et al. GOLPH3 modulates mTOR signalling and rapamycin sensitivity in cancer. Nature 2009, 459, 1085–1090.

- Kuna, R.S.; Field, S.J. GOLPH3: A Golgi phosphatidylinositol(4)phosphate effector that directs vesicle trafficking and drives cancer. J. Lipid Res. 2019, 60, 269–275.

- Makhoul, C.; Gosavi, P.; Gleeson, P.A. Golgi Dynamics: The Morphology of the Mammalian Golgi Apparatus in Health and Disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 112.

- Halberg, N.; Sengelaub, C.A.; Navrazhina, K.; Molina, H.; Uryu, K.; Tavazoie, S.F. PITPNC1 Recruits RAB1B to the Golgi Network to Drive Malignant Secretion. Cancer Cell 2016, 29, 339–353.

- Saraste, J.; Prydz, K. A New Look at the Functional Organization of the Golgi Ribbon. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 171.

- Stow, J.L.; Murray, R.Z. Intracellular trafficking and secretion of inflammatory cytokines. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2013, 24, 227–239.

- Robbins, E.; Gonatas, N.K. The Ultrastructure of a Mammalian Cell during the Mitotic Cycle. J. Cell Biol. 1964, 21, 429–463.

- Valente, C.; Colanzi, A. Mechanisms and Regulation of the Mitotic Inheritance of the Golgi Complex. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 3, 79.

- Petrosyan, A. Unlocking Golgi: Why Does Morphology Matter? Biochemistry 2019, 84, 1490–1501.

- Petrosyan, A. Onco-Golgi: Is Fragmentation a Gate to Cancer Progression? Biochem. Mol. Biol. J. 2015, 1, 16.

- Chia, J.; Goh, G.; Racine, V.; Ng, S.; Kumar, P.; Bard, F. RNAi screening reveals a large signaling network controlling the Golgi apparatus in human cells. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2012, 8, 629.

- Lin, S.C.; Chien, C.W.; Lee, J.C.; Yeh, Y.C.; Hsu, K.F.; Lai, Y.Y.; Lin, S.C.; Tsai, S.J. Suppression of dual-specificity phosphatase-2 by hypoxia increases chemoresistance and malignancy in human cancer cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 1905–1916.

- Lee, J.E.; Patel, K.; Almodóvar, S.; Tuder, R.M.; Flores, S.C.; Sehgal, P.B. Dependence of Golgi apparatus integrity on nitric oxide in vascular cells: Implications in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Physiology. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011, 300, H1141–H1158.

- Lee, J.E.; Yuan, H.; Liang, F.X.; Sehgal, P.B. Nitric oxide scavenging causes remodeling of the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus and mitochondria in pulmonary arterial endothelial cells. Nitric Oxide Biol. Chem. 2013, 33, 64–73.