Multiple myeloma (MM) accounts for about 10% of hematological malignancies. It is a plasma cell malignancy that originates from the post-germinal lymphoid B-cell lineage, and is characterized by an uncontrolled clonal growth of plasma cells. The discovery of non-coding RNAs as key actors in multiple myeloma has broadened the molecular landscape of this disease, together with classical epigenetic factors such as methylation and acetylation. microRNAs and long non-coding RNAs comprise the majority of the described non-coding RNAs dysregulated in multiple myeloma, while circular RNAs are recently emerging as promising molecular targets.

- CRISPR-Cas

- long non-coding RNA

- microRNA

- multiple myeloma

- non-coding RNA

1. Introduction

2. Methylation

DNA methylation is a central epigenetic modification in cancer. It plays an important regulatory role in transcription, chromatin structure and genomic stability, X chromosome inactivation, genomic imprinting, and carcinogenesis [3]. Global hypomethylation in cancer cells was one of the first epigenetic alterations found in carcinogenesis. Moreover, certain genes are inactivated due to hypermethylation of CpG islands in regulatory regions. This process is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMT) and involves the addition of a methyl group to the carbon 5 position of the cytosine ring in the CpG dinucleotide, generating a 5-methylcytosine (5mC) [4]. The opposite process of demethylation is mainly catalyzed by TET enzymes, which can oxidize 5mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), 5-formylcytosine (5fC), and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC). These oxidized products can then be removed by base excision repair and substituted by cytosine in a locus-specific manner [5]. However, despite the finding of TET2 loss-of-function mutations in some hematological malignancies, there is very few knowledge about their role in MM [6]. Methylation patterns have been shown to be different depending on the stage of MM progression. In non-malignant stages and MGUS, demethylation occurs mainly in CpG islands. At the transition from MGUS to MM, the key feature is a strong loss of methylation, associated with genome instability. In malignant stages, changes in methylation are widespread in the genome, outside of CpG islands, and affect various pathways, such as cell cycle and transcriptional activity regulators [7]. DNMT3A is hypermethylated and underexpressed in MM, leading to a global hypomethylation. Interestingly, DNA hypermethylation in B-cell specific enhancers seems to be a key feature of MM-staged cells. These hypermethylated regions are located in binding sites of B-cell specific transcription factors, thus leading to an impaired expression of those and, consequently, a more non-differentiated cell profile in MM cells. This hypermethylation in B-cell-specific enhancers has been found in stem cells; it is progressively eliminated in non-malignant B cells and reacquired again in MM cells [8]. Genomic studies have been performed to explain the role of promoter hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes. Preliminary studies revealed that in MM patients, there was aberrant methylation in genes such as SOCS-1, p16, CDH1, DAPK1, and p73. Hypermethylation of crucial tumor modulating genes, such as GPX3, RBP1, SPARC, and TGFBI has been associated with a significantly shorter overall survival, independently of age, International Staging System (ISS) score, and adverse cytogenetics [9][10][9,10]. Moreover, several signaling pathways were found to be dysregulated in MM. STAT3 overexpression due to promoter hypermethylation was associated with an adverse prognosis and was mainly induced by IL-6 signaling [11]. DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (DNMTi), such as 5-azacytidine, were shown to revert hypermethylation and exerted synergistic anti-MM effects with bortezomib [12]. Therefore, several clinical trials have been conducted to assess DNMTi efficacy in combination with anti-MM agents, such as lenalidomide or dexamethasone [13].3. Acetylation

Acetylation is one of the major reversible post-translational modifications that introduces an acetyl group on histone lysine residues, thus modifying the gene expression pattern. It involves a dynamic process, consisting of a balance between the activity of histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs). This balance serves as a key regulator that influences many cellular processes such as cell cycle, chromatin structure, and gene expression [4]. HATs catalyze the attachment of acetyl groups, resulting in a less condensed chromatin structure. CREB-binding protein CBP/p300 family is a HAT type A enzyme, whose mutations are often related to cancer development. It is located in the nucleus and involved in the acetylation of histones. CBP/p300 is dysregulated in hematological malignancies [14][21] and, in the case of MM, inhibition of CBP/p300 has been shown to induce cell death via the reduction of IRF4 expression [15][22]. This could open a promising therapeutic strategy but however, the majority of studies are focused on HDACs, which catalyze the amide hydrolysis of acetylated lysines. HDACs constitute a family of 18 proteins subdivided into four classes based on homology to yeast HDACs: class I (HDAC1-3, HDAC8), class IIa (HDAC4-5, HDAC7, HDAC9), class IIb (HDAC6, HDAC10), class III (SIRT1-7), and class IV (HDAC11). Alterations in their activity have been discovered in a broad range of tumors, including MM. Their targets include histones but also non-histone proteins such as p53, Hsp90, and p65 NF-κB [16][23]. The essential role played by HDACs in cancer and MM progression has led to the development of HDAC inhibition strategies. Pan-HDAC inhibitors seem to show stronger clinical inhibition of HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3, and HDAC6 than other HDACs. This suggests that their anti-tumor activity may focus on class I and class IIb HDAC inhibition [17][24]. Several HDAC inhibitors, such as romidespin (class I HDAC inhibitor) or panobinostat (pan-HDAC inhibitor) induce high cytotoxicity against MM cells, especially in combination with proteasome inhibitors such as bortezomib. Nevertheless, due to the wide range of targets, they also showed unfavorable side effects in clinical trials [18][25]. To avoid these problems, the development of selective HDAC inhibitors has become critical in MM research. To date, HDAC6 inhibitors (i.e., ricolinostat) are the ones showing encouraging results in MM treatment. HDAC6 is essential for aggresome formation, an alternative clearance pathway that is activated in response to proteasome inhibition to eliminate misfolded proteins [18][25]. The synergistic inhibition of proteasome and aggresome pathways leads to the accumulation of misfolded proteins, resulting in cell death [19][26], therefore, unveiling a promising strategy involving the combination of HDAC6 and proteasome inhibitors to tackle resistance in MM.4. Non-Coding RNAs

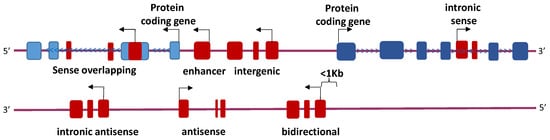

Efforts in the study of the genome have classically focused on protein-coding genes that include only a small percentage of the mammalian genome. In the last years, a special emphasis has been placed on the non-protein-coding genome. The development of genomic and transcriptomic technologies has highlighted that 70% of the transcribed human genome corresponds to ncRNAs [20][27]. ncRNAs are divided in two groups: structural and regulatory ncRNAs. Structural ncRNAs include transfer RNAs (tRNAs), ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs), small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs), and small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs). These ncRNAs are part of the machinery involved in protein synthesis. Regulatory ncRNAs are divided depending on their size: microRNAs (miRNAs) and PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) are less than 200 nucleotides long, while long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) comprise the biggest. Another type of ncRNAs are circular RNAs (circRNAs), which mainly function as miRNA sponges [21][28].4.1. microRNAs

miRNAs are 19 to 25 base-pair-long ncRNA molecules that trigger the translational repression, and sometimes degradation, of target messenger RNAs (mRNAs) with complementary sequences. Alterations in miRNAs have raised special interest in cancer research, including MM (Table 1). miRNAs constitute one of the central and most-studied post-transcriptional regulator components affecting myelomagenesis, MM progression, development, and prognosis. miRNAs can be classified into tumor-suppressive miRNAs, when they target an oncogenic gene, or oncogenic miRNAs, when they target a tumor suppressor gene, and they are tissue-specific.|

Activity/Pathway Affected |

miRNA |

Status 1 |

Target |

References |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Enhances PI3K/Akt pathway |

miR-20a |

|

] | ||||||

|

ANGPLT1-3 |

miR-30a-3p | EGR2 | , PTEN |

[59] |

|||||

MAF | |||||||||

|

miR-21 |

|

PIAS3 |

|||||||

|

miR-25-3p |

|

PTEN |

|||||||

|

BM742401 |

|||||||||

|

CRNDE | |

Not described |

miR-451 Inhibit myeloma cell migration, biomarker |

IL6R |

|||||

|

CRNDE |

|||||||||

|

H19 |

|

miR-451 |

miR-29b |

HDAC4 and MCL1 ceRNA |

miR-221/222 | ||||

|

DARS-AS1

|

| ||||||||

|

MALAT1 |

|

|

miR-509-5p PUMA, PTEN, CDKN1B RBM39 |

, p27 |

|||||

Enhances mTOR pathway, hypoxia phenotype | |||||||||

FOXP1 |

miR-410 |

H19 |

KLF10 |

miR-29b |

|||||

ceRNA, biomarker | |||||||||

|

HOTAIR |

| ||||||||

|

miR-1271-5p |

SOX13 |

Enhances mTOR pathway |

miR-19b |

|

Not described TSC1 |

||||

Enhances JAK/STAT pathway | |||||||||

|

MEG3 |

miR-181a |

BCL2L11 |

miR-135b, miR-642a |

MALAT1 |

DEPTOR |

HMGB1, miR-509-5p, miR-1271 |

|||

Contributes to genomic stability, ceRNA, biomarker | |||||||||

|

MEG3 |

|

miR-181a | ] | [95] |

|||||

|

OPI5-AS1 | |||||||||

|

MIAT |

miR-29b |

HDAC4 and MCL1 |

Related to a hypoxia phenotype |

miR-210 |

|||||

|

NEAT1 |

miR-214 |

|

CD276 DIMT1 |

Promotes osteogenic differentiation, biomarker, ceRNA [31] |

|||||

] | [ | ][91] |

miR-1305 |

||||||

|

MIAT |

|

MDM2 | |||||||

|

miR-193a | | , IGF1, FGF2 |

|||||||

|

MCL1 | miR-29b |

[59 Inducible by bortezomib, ceRNA, biomarker |

][66] |

Disrupts PRC2 activity |

miR-124 |

|

|||

|

NEAT1 |

|

miR-214, miR-193a | EZH2 |

||||||

Downregulates genes involved in DNA repair, enhances Wnt/β-catenin pathway, ceRNA |

|

||||||||

|

OPI5-AS1 |

miR-410 |

KLF10 |

Modulates microenvironment |

miR-146a |

|

Not described |

|||

|

miR-155 |

|

Not described |

|||||||

|

Promotes proliferation, circulating miRNAs |

miR-17-92 |

|

BIM |

||||||

|

miR-221/222 |

|

||||||||

|

Circulating miRNA |

miR-1 |

|

Not described |

||||||

|

miR-133a/b |

|

Not described |

|||||||

|

miR-135b |

|

HIF1A |

|||||||

|

miR-146b |

|

Not described |

|||||||

|

miR-181a |

|

BCL2L11 |

|||||||

|

NR_046683 |

|

Not described |

|||||||

|

PRAL |

miR-210 |

DIMT1 |

Biomarker |

[84 |

miR-410 |

||||

|

SNHG16 |

miR-342 | ceRNA |

RUNX2 |

||||||

|

PDIA3P |

|

||||||||

|

UCA1 |

miR-331-3p |

c-Myc |

IL6R Regulates proliferation |

||||||

|

RUNX2-AS1 |

|||||||||

|

|

miR-1271-5p |

SOX13 and HGF RUNX2 pre-mRNA |

Promotes osteogenesis |

||||||

|

SMILO |

|

Not described |

Regulates proliferation |

||||||

|

SNHG16 |

|

miR-342 |

ceRNA |

||||||

|

UCA1 |

|

miR-1271-5p, miR-331-3p |

ceRNA |

||||||

|

XLOC_013703 |

|

IKKA |

Represses NF-κB pathway |

miR-214 |

|

CD276 |

|||

|

Represses JAK/STAT pathway |

miR-125b |

|

IL6R, STAT3, MALAT1 |

||||||

|

miR-331-3p |

|

IL6R |

|||||||

|

miR-375 |

|

PDPK1 |

|||||||

|

miR-451 |

|

IL6R |

|||||||

|

let-7b-5p |

|

IGF1R |

|||||||

|

Regulates cyclin activity |

miR-26a |

|

CDK6 |

||||||

|

miR-28-5p |

|

CCND1 |

|||||||

|

miR-30a-3p |

|

MAF |

|||||||

|

miR-338-3p |

|

CDK4 |

|||||||

|

miR-340-5p |

|

CCND1, NRAS |

|||||||

|

miR-196a/b |

|

CCND2 |

|||||||

|

Regulates proliferation |

miR-22 |

|

c-Myc |

||||||

|

miR-29a |

|

c-Myc |

|||||||

|

miR-34a |

|

BCL2, CDK6, NOTCH1, c-Myc, MET, IL6R |

|||||||

|

miR-193a |

|

MCL1 |

|||||||

|

miR-497 |

|

BCL2 |

|||||||

|

miR-767-5p |

|

MAPK4 |

|||||||

|

miR-874-3p |

|

HDAC1 |

|||||||

|

miR-1180 |

|

YAP |

|||||||

|

Prevents angiogenesis |

miR-15a/16 |

|

BCL2, VEGF, IL17 |

||||||

|

Regulates acetylation |

miR-29b |

|

HDAC4, MCL1 |

||||||

|

Regulates transcriptional activity |

miR-509-5p |

|

FOXP1 |

||||||

|

miR-1271-5p |

|

SOX13, HGF |

|||||||

|

Prevents hypoxia phenotype |

miR-199a-5p |

|

HIF1A, VEGFA |

||||||

|

Prevents osteolytic activity |

miR-342 |

|

RUNX2 |

||||||

|

miR-363 |

|

RUNX2 |

1 Arrow up indicates overexpression of the miRNA, and arrow down indicates underexpression of the miRNA.

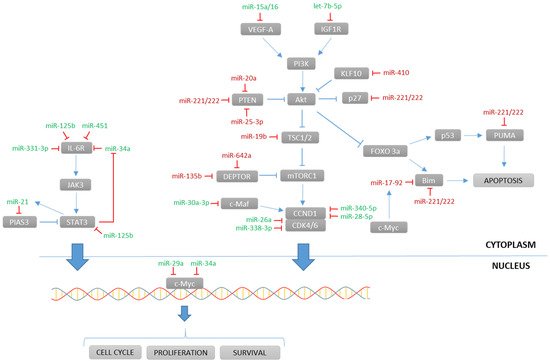

miRNAs may act in clusters, where a group of miRNAs have their expression regulated concomitantly. One of the largest clusters involved in MM is miR-17-92, a six-member polycistronic cluster encoding for six individual miRNAs: miR-17, miR-18a, miR-19a, miR-19b, miR-20a, and miR-92a. Some of these miRNAs are known for regulating the PTEN/PI3K/Akt pathway (Figure 1). This cluster was demonstrated to take part in controlling cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, as it was positively regulated by c-Myc, which conferred to this cluster a key role in MM tumorigenesis [28][35]. Several studies have empirically proven, using functional assays, that BIM is the direct target of miR-17-92. This was confirmed in MM cells with upregulated miR-17-92 that showed an increased expression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 [28][71][35,78]. Despite their coordinated role, some of the miRNAs belonging to this cluster also had specific functions. Interestingly, miR-20a was highly expressed in bone marrow samples of MM patients when compared to healthy donors. The introduction of a synthetic substitutive miR-20a (mimic-based approach) showed an increased growth rate and decreased apoptosis in the U266 MM cell line, and a promoted tumor growth in a SCID/NOD mouse xenograft model [22][29]. PTEN was shown to be a downstream target of miR-20a, pointing out the PTEN/PI3K/Akt pathway as altered by miR-20a [23][30]. miR-19b specifically targeted the tumor-suppressive co-chaperone TSC1 and activated the mTOR pathway, which promoted cancer stem cell (CSC) proliferation [29][36].

4.2. Long Non-Coding RNAs

|

lncRNA |

Status 1 |

Target |

Activity/Pathway Affected |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

lncRNA |

miRNA |

Gene |

References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ANGPLT1-3 |

|

miR-30a-3p |

ceRNA |

[52 |