2. Plasma Treatment Method

Plasma is a partially or fully ionized gas that can be ignited at low atmospheric conditions and consists of charged species (electrons and negative and positive ions), neutral species (atomic and/or molecular radicals and non-radicals), electric fields, and photons. One of the earliest applications of plasma for treatment of seeds was studied in early 1960s, when the effects of glow discharge on cotton, wheat, alfalfa, red clover, sweet clover, beans, and several varieties of grass seeds were investigated. It was shown that the plasma treatment influences seed germination, moisture adsorption, and apparently reduces hard-seed content in legumes

[24][25][26][27][24,25,26,27]. Since then, studies on plasma treatment of seeds have been expanded by using various kinds of plasma devices, which allow detailed studies on physical, chemical, and biological mechanisms of plasma that can be triggered by analysis of plasma components

[28].

In the past decades, LTP at atmospheric pressure has opened up a new research field in biology and medicine

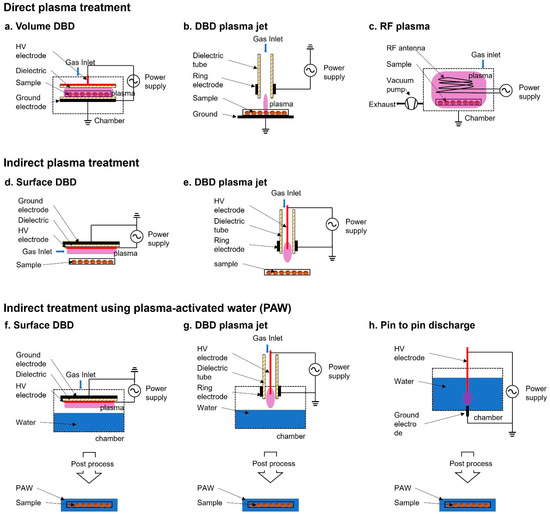

[29][30][29,30]. Plasma treatment of seeds has been divided into two methods—direct and indirect—based on the contact of the plasma with the samples. For plasma treatment, plasma sources, such as dielectric barrier discharge (DBD)

[31][32][33][34][35][36][37][31,32,33,34,35,36,37], radio frequency (RF) plasma

[38][39][40][41][42][43][44][38,39,40,41,42,43,44], and atmospheric pressure plasma jet (APPJ)

[15][45][46][15,45,46], have been used (

Figure 1). The treatment is performed by controlling operating parameters, such as electrode structure, power source (voltage, frequency, and waveform), discharge gas (air, Ar, He, etc.), and other conditions (gas flow, gas pressure, gas temperature, etc.).

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of plasma devices used for seed treatment. (a–c) Direct plasma treatment: (a) volume dielectric barrier discharge (DBD), (b) DBD plasma jet, (c) Radiofrequency (RF) plasma; (d,e) Indirect plasma treatment where the sample is not directly in contact with the plasma discharge: (d) surface DBD, (e) DBD plasma jet; (f–h) Indirect treatment using plasma-activated water (PAW), (f) surface DBD, (g) DBD plasma jet, (h) pin-to-pin discharge.

In direct plasma treatment, the plasma devices usually consist of a place to plant seeds in the container module, where they are exposed to the plasma generated by the generator and electrode. Because the surface area of Surface DBD (SDBD) is relatively wider compared with that of other plasma devices, it has been more commonly used than other plasma devices for biological applications. For example, SDBD plasma device has been widely used in the germination and growth of Arabidopsis, barley, bell pepper, maize, pea, quinoa, and wheat

[33][47][48][49][50][51][33,47,48,49,50,51]. The exposed seeds in the discharge area are directly affected by charged particles, reactive species (such as OH radicals, singlet oxygen, ozone, and hydrogen peroxide), electric fields, and photons (visible/ultraviolet (UV) radiation). A combination of these components is believed to be the main factor that promotes seed germination and growth. During the exposure, the seed surface interacts with the short lived and long-lived radicals, which appear due to secondary reactions.

In indirect treatment, the sample is not exposed to the plasma itself. The plasma does not directly affect the samples, but a gas-phase active species generated by the plasma and PAW affect the sample. Plasma-treated water causes changes in the physicochemical properties and PAW participates in the signaling pathway and eventually promotes seed germination, root and vegetative growth, and plant reproduction

[52][53][52,53].

PAW, especially under atmospheric conditions, is known to change the electrical conductivity, pH, concentration of nitrite (NO

2−), nitrate (NO

3−), ozone (O

3), and hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2)

[54]. These changes in physicochemical properties and components mainly contribute to the benefits of plasma treatment for seed germination and plant growth. Most research on seed treatment has been focused on the inhibition of microbial growth on the seed surface. The application of PAW for inhibition of microorganisms is usually linked to the increasing acidity with the duration of plasma treatment

[55][56][57][55,56,57]. Moreover, the reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) content is increased, which also inhibits microbial growth that later affects seed germination and RONS functions in seed priming

[10].

In addition to seed priming, the high nitrate and nitrite content in PAW is believed to be the major factor contributing to the improvement of plant growth under PAW irrigation because it can act as a substitute for nitrogen source. Hence, the concept of “plasma-fertilizer” was established. This concept is considered important because nitrogen is the backbone of all metabolic processes that directly affect plant growth. In addition, “plasma fertilizer” is one of the eco-friendly alternatives of nitrogen source that reduces the disadvantages associated with the use of chemical fertilizers. Therefore, it is not surprising that this is the major topic for future studies on plasma treatment for plant cultivation

[58][59][60][61][58,59,60,61].

3. Chemical and Physical Effects of Plasma Treatment

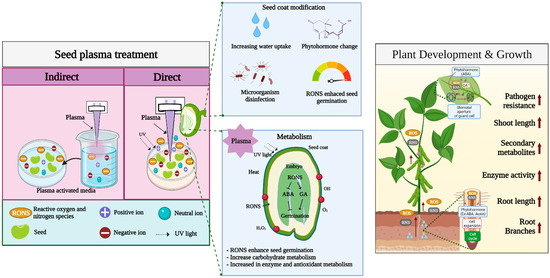

Direct plasma treatment of the seed surface is the most common treatment performed in seed germination studies. When the plasma contacts the seed surface, it changes the seed coat, resulting in reduced germination time and rapid growth and development

[14][62][14,62]. The positive effects of plasma treatment of seeds have been observed in several species of horticultural crops

[15]. Plasma studies in horticultural crops show that atmospheric plasma increases the germination rate and growth rate in radish, pepper, and tomato in correlation with the duration of treatment

[20]. In addition to the germination of tomato seeds, use of helium plasma for seed priming increases its overall growth compared with that in control

[15]. It is well known that plasma treatment of seeds is mainly affected by RONS. The production of RONS from plasma is also regarded as a major factor in enhancing seed germination, seedling growth, and plant defense. In addition, seed surface or seed coat changes are categorized as mechanical changes. Moreover, factors such as seed sterilization, heat, UV irradiation, ionization, and electromagnetic fields generated by plasma devices are also believed to play roles in seed germination induced by plasma treatment.

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Overview of plasma treatment effects on seed germination and plant growth.

3.1. Chemical Effects of Plasma Treatment

Several terms have been used in literature for reactive species to describe the oxygen radicals and non-radicals. Reactive species are also grouped into reactive oxygen species (ROS: O

2−, H

2O

2, O

3, etc.) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS:

•NO,

•NO

2, ONOO

−, etc.). Some common reactive species include ozone (O

3), hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2), superoxide anion, peroxyl, nitric oxide, nitrogen dioxide, and peroxynitrite

[63][64][65][63,64,65]. Reactive species generated from plasma treatment are believed to be the major factors affecting seed germination and plant growth. However, mechanisms underlying the effects of ROS and RNS on seed germination and development are not fully understood. There are few hypotheses about how the external ROS affect seed germination. One hypothesis is that external ROS are detected and perceived by the cells in seeds that induce signal transduction from the outer layer of the seeds. The other hypothesis is that during imbibition, water is the key factor in the absorption of ROS into the cell layers of the seeds. Thus, it increases the respiration of seeds and triggers a chain reaction of sugar oxidation to release metabolic energy in the form of ATP

[47]. Therefore, the involvement of ROS in the respiration pathway is considered a primary and secondary trigger in seeds that causes transition from dormancy to metabolic activity.

A previous study showed the presence of external ROS in certain amounts in water during imbibition and also showed that wet seeds may trigger faster signaling in the intercellular process; however, the effect of ROS on dry seeds is hardly understood. There is a possibility that the effect of ROS on dry seeds is minimized or delayed. During plasma treatment, ROS penetrates the seeds, but no specific mechanism occurs until the start of imbibition

[66]. However, how ROS are stored during the period before imbibition remains unknown. In addition, this theory does not fully explain how long-term storage after plasma treatment still a positive effect on the germination and growth of seeds compared with those of untreated seeds, especially when ROS are known to be mostly short-lived

[67]. Biochemical changes in plasma-treated seeds apparently continue to occur even long after the seeds are treated

[20][68][20,68]. These changes are related to gene expression, the oxidative process, protein concentration and hormones. It is believed that plasma treatment increases the pore size of the seed coat, which increases water imbibition and ROS absorption, leading to genetic regulation of seeds

[69]. Other possible ways by which seeds and plants might absorb RONS generated from plasma treatment could be through the bypassing of protein channels, named aquaporins, which are mainly used for water transport

[70]. It is important to note that, in addition to transport via aquaporins, ozone is absorbed through stomata in the seedlings and mature plants. Therefore, it has been observed that the accumulation of ROS in leaves through stomata and micropores is the main pathway by which ROS can travel further to other plant tissues. It was also shown that excessive absorption of ROS by plants could result in chloroplast damage

[71].

A relatively small amount of H

2O

2 (0.12 ppm) in PAW, generated from a plasma device, increased the seed germination rate in tomato and pepper seeds

[20]. In Arabidopsis, PAW containing 17–25.5 mg/L H

2O

2 had a positive effect on germination and seedling growth

[14]. Among RNS, low nitrate concentration (100 ppm or less) enhances seed germination and seedling growth in plants, but the growth tends to be inhibited above 100 ppm

[20][72][73][74][20,72,73,74]. However, plants apparently have their own nitrate and ROS sensitivity and show a dosage-dependent growth pattern.

One of the prominent members of reactive species, which is abundantly detected in plasma treatment, is hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2). A previous study on the involvement of H

2O

2 in seed germination and seedling growth revealed its role in the absorption mechanism, signaling pathway, regulation of gene expression, protein modification, and other related factors

[75]. The absorption of H

2O

2 into the cells occurs mainly through diffusion and is dependent on the anion channels; inside the cell, it breaks down into singlet oxygen and hydroxyl, thus, allowing easy transfer between cells

[70][76][70,76]. During germination, H

2O

2 mediates the regulation of abscisic acid (ABA) catabolism and gibberellic acid (GA) biosynthesis

[77]. In addition, upon exposure of seeds to external H

2O

2, the endogenous H

2O

2 levels also increase and induce several oxidative pathways, such as carbonylation and lipid peroxidation

[78]. Moreover, the presence of H

2O

2 in cells is regarded as a priming factor that involves complex changes in the proteome, transcriptome, and hormone levels

[78].

Ozone, as one of the major ROS, was shown to be responsible for improved seed germination and induction of protein expression in seeds

[79][80][79,80]. Ozone generated during the presence of UV radiation can eventually generate superoxide and hydroxyl radicals in the seed coat, which could be one of the main reasons for how the combination of external physical damage of the seed coat combined with chemical stimulus of the accumulated radicals works synergistically to increase germination. However, it is important to note that different device configurations produce different concentrations of ozone. Moreover, the purpose of treatment also determines the ozone concentration required. Postharvest treatment with 0.3 ppm ozone in combination with cold storage could inhibit the decay process and reduced severe infection in peach and table grapes

[81][82][81,82]. In strawberry, plasma treatment using different sources of gas has been investigated; it was observed that plasma treatment for 5 min could produce 600–2800 ppm ozone that had a positive effect on microbial disinfection and strawberry freshness

[83]. Similarly, various ozone concentrations were investigated in the plasma treatment of seeds. In Arabidopsis seeds, the effects of treatment with 200 ppm ozone, generated from a plasma device, for 10 min on seed coat modification were studied

[84]. A low concentration of ozone (~1–5 ppm) is effective in plant growth by killing larvae in the soil and in fresh cut green leaf lettuce

[85]. Interestingly, a similar concentration of ozone (~1–4 ppm) generated from surface discharge successfully reduced the number of nematodes and induced plant growth

[86].

The biochemical mechanism underlying the effects of plasma treatment on seeds is very closely related to the metabolism of antioxidant enzymes. The seed coat may contain proteins or enzymes, such as NADPH oxidase, superoxide dismutase (SOD), and peroxidase (POD), which can convert the substrate into signaling molecules such as H

2O

2. Plasma treatment of wheat seedlings resulted in increased isoenzyme activities, such as POD and phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL), which are crucial for the production of polyphenols, which also participate in plant defense

[87][88][87,88].

Another area of focus in plasma treatment is the potential application of RNS produced from plasma–liquid interaction as a liquid fertilizer for plant growth. Various approaches have been explored to obtain the most suitable device and treatment method for the production of high amounts of RNS in the solution. For example, a large volume of glow discharge has been tested as a liquid fertilizer in radish, tomatoes, and marigolds

[89]; bubble discharge has been investigated in the cultivation of spinach, radish,

Brassica rapa, and strawberry

[90][91][92][90,91,92]; a plasma jet has been used for plasma-assisted nitrogen fixation for corn

[93]. Collectively, these reports demonstrate the potential of plasma fertilizers as an alternative and a more eco-friendly approach for nitrogen source for plant cultivation. However, one of the challenges in plasma-assisted nitrogen fixation is the low pH or increased acidity of the solution treated with plasma, which damages the seed and plant exposed to such solutions. Plant growth is limited under acidic environment

[94]. Therefore, studies on controlling the balance and on methods to overcome the acidity of plasma-activated solutions are being considered a priority in the plasma field. Lamichhane et al. recently demonstrated an innovative approach to control the acidity of plasma-treated water using a combination of chemical additives including Mg, Al, or Zn, which could neutralize via the reduction in pH

[93]. Moreover, the presence of these additives increases the rate of reduction of nitrogen to ammonia, which results in the improvement of germination rate and seedling growth

[93].

Inactivation of microbes by plasma treatment has been used as the fundamental technology in medicine and food processing

[95][96][97][95,96,97]. Microbial inactivation, resulting from plasma treatment of seeds, also plays important roles in germination. The seed surface is usually exposed to the environment, which contains many types of particles, contaminants, and microbes that could have negative effects on seed germination. For example, in grain crops, such as rice, wheat, oat, and barley, the growth of

Fusarium on the seed surface affects germination

[98]. It is known that fungal infections on seeds often damage their viability and potentially reduce the yield. Moreover, fungal pathogen on seeds can also lead to a seed-borne infection, which can cause abundant yield loss. The plasma treatment of seeds has been shown to have positive effects on seed sterilization, including removal of fungal spore on the seeds. In rice, direct treatment using micro corona discharge of SDBD can inactivate the microorganisms on the husk, which leads to higher germination compared with that in untreated seeds

[99]. This finding emphasizes the incorporation of Ar and air in plasma that would result in the production of ROS and RNS, which decontaminate and inactivate fungi on the seed surface. Another study using indirect treatment with arch discharge plasma showed successful inactivation of

Fusarium fujikuroi (a fungal pathogen) in a submerged rice seed suspension; however, fungal spores are more effectively inactivated using ultrasonic waves as a source of ozone and shock-wave

[100]. Collectively, these two examples show that both direct and indirect treatments are effective in inhibiting the fungus through the production of ROS and RNS. Moreover, positive results for microbial inactivation or sterilization of seeds were also confirmed in many different seeds, such as wheat, barley, oat, lentils, maize, chickpea, sunflower, and scots pine

[12][101][102][103][104][12,101,102,103,104].

The mechanism underlying the effects of plasma treatment in the inactivation of microorganisms has been well-investigated using different device types, exposure times, power, gas sources, and other factors. Compared with conventional seed sterilization using active chemicals, the mechanism of plasma disinfection is often considered complex due to variations in devices and plasma components

[105]. However, the general agreement for the use of plasma treatment for disinfection is due to the production of reactive species, exposure to which triggers a complex sequence of events in the microbe, resulting in the antimicrobial activity

[106]. For example, exposure to ROS directly triggers molecular damage in cells, including DNA breakage, lipid peroxidation, and carbonylation of proteins

[107][108][107,108]. Moreover, combined action of RNS and ROS is important for antibacterial activity. The effect of plasma with high content of ROS and RNS is more than that of plasma-treated water on the antimicrobial activity

[109]. UV exposure also plays an important role, especially in the inactivation of bacteria using plasma treatment. It is known that mechanism of action of UV exposure may be related to several specific mechanisms, including direct destruction of genetic material, breaking of chemical bonds in organic compounds, and the phenomenon of plasma etching (UV-induced etching)

[110][111][112][110,111,112].

Other applications of plasma treatment include the inactivation of viruses. In the field of plasma biomedicine, the inactivation of coronavirus using plasma devices has recently garnered a lot of attention and proved to be effective in treating viral infection and associated diseases

[113][114][115][113,114,115]. In plants, potential applications of plasma treatment of virus-related diseases have been reported. Potato virus Y (PVY) homogenized in water was successfully inactivated by plasma treatment for 1 min

[116]. A sample of pepper mild mottle virus (PMMoV) in water was also successfully inactivated using 99% argon and 1% oxygen plasma jet in 5 and 3 min

[117]. As for the inactivation of bacteria, the mechanism of virus inactivation is primarily through the production of reactive species (ROS and RNS) with various physical effects, and the treatment could damage the virus particle and degrade viral DNA/RNA

[118][119][118,119].

3.2. Physical Effects of Plasma Treatment

Plasma treatment of seeds, especially direct treatment, is considered to have a similar principle to plasma etching on the seed surface

[120]. It is shown that seed coat modifications are presumably highly dependent on the type of plasma devices, power, and duration of the treatment. For example, treatment of Arabidopsis, wheat, radish, and oat seeds showed no distinct surface modifications based on seed coat morphology

[121][122][123][124][121,122,123,124]. However, other studies revealed seed coat degradation by plasma treatment, which was observed using scanning electron microscope (SEM), in different plant seeds such as Arabidopsis, cotton, wheat, mimosa (

Mimosa caesalpiniaefolia), erythrina (

Erythrina velutina), pea, and onion

[34][35][125][126][127][128][129][34,35,125,126,127,128,129]. Therefore, the effect of plasma treatment on seed germination may be due to the mechanical factors of seed coat modification, especially when treated with appropriate plasma device and configuration.

The seed coat protects the seed from the external environment and regulates the water absorption. Imbibition must occur in the correct ratio; otherwise, seeds may be damaged if imbibition is too slow or too fast

[69]. Plasma treatment affects seed germination differently in different seeds of various species and different plant families, even for different variety and ecotype, and generally, a different setup is needed for optimum treatment condition. The seed coat consists of cuticle, epidermis, hypodermis, and parenchyma cells. The degradation of cuticle layers will allow water to be absorbed further into inner layers. Plasma treatment helps in the removal of lipid layers on the cuticle and epidermis, which accelerate the germination

[130]. In Arabidopsis seeds, modifications in the composition of lipid compounds in the seed coat was detected after plasma treatment

[37]. Interestingly, Arabidopsis seed coat mutants,

gl2 and

gpat5, and Col-0 were examined under plasma treatment; the germination rate was increased in plasma-treated seeds, even under osmotic and saline stress conditions, whereas the germination ratio in

gpat5, with defective cuticle layers on the seeds, was not rescued by plasma treatment due to less permeability and more sensitivity to plasma processing. POD activity in testa and endosperm tissues was detected, where the major POD function occurred in ruptured seeds. This shows that in plasma-treated seeds, the structure and composition of lipid compounds are changed before germination and metabolism changes after germination

[37].

Seed surface modifications are usually investigated using light microscope or SEM. In addition, biochemical analysis is also performed to confirm the differences in seed coat content, such as lignin, cutin, polysaccharides, and other ROS-related proteins. Indirect treatment using plasma-treated water was also performed to determine the seed wettability, which showed possibilities of combined mechanism involving seed perforation and lower water tension that increases the surface area and ability of imbibition. Seed coat modifications are closely related to water permeability and water affinity on seed surface, also known seed wettability

[131]. The increase in seed wettability improves the permeability of seeds to water, and thus, the imbibition process is accelerated. The wettability has been known to be majorly affected by the morphology and chemistry of seeds. Morphologically, plasma treatment causes surface etching or surface erosion that increases the roughness of the seed surface, resulting in the increase in seed volume ratio, and thus, wettability is increased. Chemically, the interaction of plasma and seed coat components affects the organic polymers in seeds, for example, it results in degradation of cutin and wax layers, thus reducing the hydrophobic activity of the seed coat and increasing water permeability

[131][132][133][131,132,133].

The heat effect of plasma treatment was examined by comparing the plasma treatment with the heat plate treatment, which shows different effects on germination

[121]. It was shown that heat is not the main factor contributing to the increase in germination of plasma-treated seeds. Although plasma treatment is regarded as “non thermal plasma or cold plasma”, the slight increase in temperature in plasma-treated seeds cannot be ignored as it may still affect the germination ratio when combined with other factors. Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are one of the important regulators of plant metabolism. They sense temperature changes, perceive signaling, and respond to protect other proteins from stress-induced damage

[134][135][136][134,135,136]. Iranbakhsh et al. confirmed that heat resulted in the induction of HSP expression in plasma-treated wheat seeds

[36]. However, it is difficult to distinguish whether heat increased the scarification of seeds, which led to the induction of germination and indirectly increased the expression of HSPs, or whether the heat generated by plasma treatment directly induced HSPs

[18]. Moreover, in a study on plasma-treated sunflower seeds, no change in the expression of HSPs was evident in proteome profiling and an ambiguous result that the treatment may not induce significant accumulation of pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins or HSPs was obtained

[42]. Remarkably, a recent study on the expression of HSP genes in maize grain treated with diffuse coplanar surface barrier discharge (DCSBD) showed induction of several HSP genes, including

HSP101,

HSP70, and

HSF17, that affected grain vitality and seedling growth

[137].

Ultraviolet light is regarded as one of the main factors in plasma sterilization, especially in the inactivation of surface microbes

[96][138][96,138]. Single spectrum UV lights, such as UV-A, UV-B, and UV-C, have been shown to increase seed germination but act differently during seedling and plant growth. Exposure of

Amberboa ramose seeds to UV-A resulted in increased germination and growth during plant development

[139]. UV-B was shown to increase the germination rate of safflower (

Carthamus tinctorious), radish, cabbage, kale, and agave seeds

[140]. However, prolonged exposure to UV-B inhibits the growth of seedlings

[140][141][140,141]. UV-C treatment in maize and sugar beet was also shown to increase germination rate and seedling growth

[142]. During plasma treatment, the possibility that UV light directly affects seed germination is considered very low due to its short exposure duration and low intensity of irradiation from the plasma sources. In some studies, it was proposed that UV irradiation due to plasma treatment may have indirect effects combined with RONS interaction and not by improvement in seed wettability

[125][143][125,143]. In addition, the nature of UV exposure could induce DNA damage, which could also affect germination and seedling growth. Short-term exposure of seeds and seedlings to UV could induce their growth by regulation of stress response, especially when the irradiation is perceived by the photoreceptor, leading to increased cell metabolism, including cell differentiation, division and elongation

[144].