Pluchea indica (L.) Less. (Asteraceae) commonly-known as Indian camphorweed, pluchea, or marsh fleabane has gained great importance in various traditional medicines for its nutritional and medicinal benefits. It is utilized to cure several illnesses such as lumbago, kidney stones, leucorrhea, inflammation, gangrenous and atonic ulcer, hemorrhoids, dysentery, eye diseases, itchy skin, acid stomach, dysuria, abdominal pain, scabies, fever, sore muscles, dysentery, diabetes, rheumatism, etc. The plant or its leaves in the form of tea are commonly used for treating diabetes and rheumatism.

- Pluchea indica

- Asteraceae

- traditional uses

- phytoconstituents

- bioactivities

- nutritional value

1. Introduction

The Asteraceae (Compositae) family is one of the largest plant families, which includes about 24,000–30,000 species and 1600–1700 genera [1][12]. Its plants are shrubs and herbs, which have been commonly used since ancient times as herbal medicines and diets all over the world [2][13]. It contains well-known species, such as sunflower, chicory, coreopsis, lettuce, daisy, and dahlias, as well as several significant medicinal plants, such as chamomile, wormwood, and dandelion [3][14].

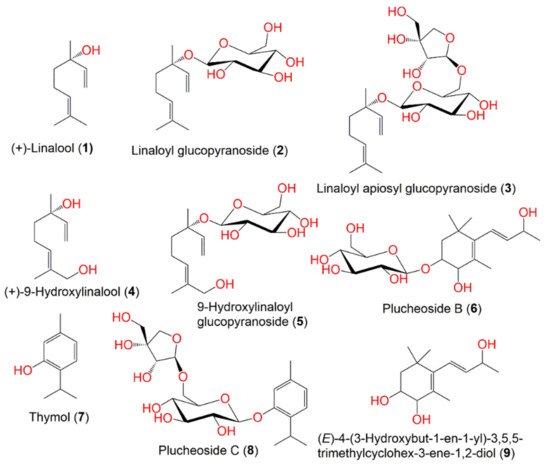

Pluchea is a flowering plants genus of the Asteraceae family, comprising about 80 species [4][15]. Its members are known as plucheas, camphorweeds, or fleabanes, and some are called sour bushes [5][16]. Pluchea indica (L.) Less. is an evergreen shrub found abundantly in salt marshes and mangrove swamps with a 1 to 2 m height that has an important role in maintaining the ecological balance in the coastal areas [6][17]. It is known as Indian camphorweed, pluchea, or marsh fleabane, Khlu (Thai), Kukrakonda, Kakronda, or Munjhu rukha (Bengali), Kuo bao ju (Chinese), luntas (Javanese), Beluntas (Malaysia, Indonesia, Bahasa), and kalapini (Philippines) [7][18]. This plant is mainly found in the subtropical and tropical zones of Asia, Africa, Australia, and America and in warm temperature regions of countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Taiwan, Australia, Mexico, and India [6][7][8][5,17,18]. A chemical investigation of this plant revealed the existence of various phytoconstituents: thiophenes, sesquiterpenes, quinic acids, sterols, lignans, and flavonoids. Additionally, this plant has wide folk uses and diverse bioactivities: anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, antioxidant, anti-microbial, and insecticidal activities. The current review summarizes the reported literature on the traditional uses, phytoconstituents, and bioactivities of this plant and isolated metabolites to highlight its positive influences on human health.

2. Phytochemistry

3. Ethnomedicinal Uses

All parts of P. indica can be used medicinally, and it has a long tradition in alternative medicine for a wide variety of ailments. In Indochina, the roots’ decoction is prescribed for fever as a diaphoretic, and its leaves’ infusion is taken internally in lumbago. The leaves and roots are utilized as an astringent and antipyretic in Patna [13][26]. It was reported that the overconsumption of the leaves for long periods of time may cause health problems, especially for individuals suffering from cardiovascular disease and hypertension due to its high contents of chloride and sodium [14][27]. In Indonesia, leave infusion/decoction is utilized as an appetite stimulant, antipyretic, digestive aid, deodorant, diarrhea solution, antitussive, and emollient [15][16][28,29]. The root decoction is utilized as an astringent and antipyretic [17][30]. In Thailand, bark and stem decoctions are utilized to treat kidney stones and hemorrhoids, respectively, and leaves are used to cure leucorrhea, inflammation, and lumbago [18][31]. Leaf tea is widely consumed in Thailand as a health-promoting drink; however, drinking this tea in large amounts increases the feeling of needing to urinate due to its diuretic effect [13][26]. Additionally, a poultice of the fresh leaf is used for a gangrenous and atonic ulcer [19][32]. Arial parts are used as an ointment to treat eye diseases and itchy skin. The plant is used for treating acid stomach, dysuria, hemorrhoids, abdominal pain, stomach cramps, scabies, fever, sore muscles, dysentery, menstruation, and rheumatism [20][21][22][23][33,34,35,36]. In Malaysia, the leaves are prescribed for leucorrhea, dysentery, rheumatism, bad body odor and breath, boils, and ulcers, while roots are used to treat lumbago, fever, headache, and indigestion [24][37]. The chopped stem bark cigarettes are smoked to relieve sinusitis pain [25][38]. Indochina, the young shoots and leaves are crushed, mixed with alcohol, and applied in baths to treat scabies, as well as to the back for lumbago and to relieve rheumatic pains [25][38]. Currently, dried leaves and their extracts have been commercially available in Thailand as herbal tea due to their blood glucose-lowering potential [26][39]. In Yogyakarta, Indonesia, the leaves are used as a galactagogue to maintain, induce, and augment maternal milk production [27][40]. It is used orally as anti-fertility for men [28][29][20,21]. In Peninsular Malaysia, it is cultivated in gardens for its young shoots, which can be eaten raw. Its leaf decoction is used to counteract fever, and the sap expressed from leaves is used for dysentery [30][41]. In Dayak Pesaguan tribes, P. indica leaves are utilized to eliminate bad body odor, increase appetite, and overcome digestive disorders [31][42].

4. Biological Activities

4.1. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

4.2. Anti-Obesity and Anti-Hyperlipidemic Activities

The leaf H2O extract (concentrations of 750 to 1000 µg/mL) markedly reduced the accumulation of lipids, suppressed adipogenesis, and modified protein, carbohydrate, glycogen, and nucleic acid concentrations in the 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Additionally, it possessed lipase inhibitory potential (concentration 250 to 1000 µg/mL) [32][69]. In another study, the leaf extract was found to prohibit pancreatic lipase with % inhibition ranging from 11.7% to 18.4% at a concentration ranging from 625 to 1000 ppm compared to orlistat (% inhibition from 26.6 to 36.6%) and epicatechin (% inhibition from 10.7 to 18.6%) at the same concentrations [33][73]. Therefore, it could be further developed into an herbal supplement for managing obesity or overweight [32][69]. P. indica tea (herb, 400 and 600 mg/kg, orally) ameliorated hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and obesity in high-fat diet-induced (HFD) mice. Moreover, it significantly lowered TG, TC, LDL-C, and perigonadal fat weight in HFD-treated mice; however, it increased HDL-C. This was related to its total phenolic and flavonoid contents (TFC), caffeoylquinic acid derivatives, betacaryophyllene, and gamma-gurjunene [34][70].

4.3. Antidiabetic Activity

Nopparat et al. reported that the pretreatment with the leaf EtOH extract (dose 100 mg/kg for 2 weeks) effectively alleviated β-cell injury produced by cytokine in STZ (streptozotocin) mice as it minimized the levels of inflammatory markers IFN-γ (interferon-γ), TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor-α), and IL-1β (interlukin1-β), along with prohibiting caspases; 3, 8, and 9, pSTAT1 phosphorylation (signal transducer and activator of transcription 1), NF-κBp65 (nuclear factor-κBp65), and iNOS. Further, it protected β-cells by boosting cell proliferation and suppressing apoptosis. The blood glucose-lowering potential of the leaf extract was attributed to the antioxidant capacities of the extract’s constituents, particularly resveratrol derivative and quercetin [11][45].

α-Glucosidase inhibitory assay-directed fractionation of the leaves’ EtOAc fraction yielded caffeoylquinic acid derivatives, 38 and 40–43, which were isolated using SiO2, RP-18 CC, and HPLC and elucidated by MS and NMR analyses. Compound 42 had the highest α-glucosidase inhibitory effectiveness among the separated caffeoylquinic acid derivatives (IC50 2.0 µM) compared to acarbose (IC50 0.5 µM), while the other compounds displayed moderate to weak activity compared to the activity of acarbose. It was found that increasing numbers of caffeoyl groups attached to the quinic acid moiety and methyl esterification of the carboxylic group in quinic acid promoted the α-glucosidase inhibitory capacity [35][57].

4.4. Insecticidal and Herbicidal Activity

Yuliani and Rahayu reported that biopesticides derived from P. indica leaf extract caused optimal mortality (81.90% at concentration 12%) of Spodoptera litura larva with LC80 9.88% and LC50 4.00%. It also markedly prohibited the seed germination of the plant weed, Amaranthus spinosus [36][88]. Therefore, the leaf extract could be a potential bioinsecticide and bioherbicide.4.5. Cytotoxicity Activity

It was found that the root EtOH extract markedly prohibited NPC (nasopharyngeal carcinoma)-TW04 and NPC-TW01 cell viability and migrations, whereas the NPC-TW04 cells had more susceptibility [37][92]. It noticeably increased NPC apoptosis that was triggered by up-regulation of pro-apoptotic protein Bax and suppression of anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 expression. Therefore, it induced the NPC cells’ apoptosis by activating p53 and regulating apoptosis-related proteins. Hence, it could be further assessed as an alternative chemotherapeutic agent for NPC [37][38][66,92]. It also prohibited K562 (human leukemia cells) proliferation, induced cell cycle arrests in the G2/M phase, and caused apoptosis [39][93]. The leaf and root aqueous extracts demonstrated prominent anti-migratory and anti-proliferative potential on HeLa and GBM8401 cells. They induced critical tumor suppressor molecules: phosphorylated-p53 and p21 and down-regulated phosphorylated-AKT. This effect was attributed to tannins, flavonoids, and the total phenolic contents of these extracts [40][91]. Moreover, the root hexane fraction exhibited a potent suppressive potential versus GBM cell growth, apparently by inducing G0/G1-phase cell cycle arrest. Further, it enhanced autophagy by increasing the formation of AVOs (acidic vesicular organelles), LC3-II expression (microtubule-associated light chain 3-II), and p38 and JNK phosphorylation [41][94].4.6. Venom Neutralizing Activity

P. indica root methanolic extract was reported to have the potential to neutralize viper venom and counter venom-induced hemorrhagic and lethality influences [42][97]. Further, 29 and 31 purified from the root extract were able to neutralize cobra and viper venom and antagonize cobra venom-induced cardiotoxicity, lethality, respiratory changes, and neurotoxicity, as well as potentiating the action of equine polyvalent snake venom antiserum in mice [43][96].4.7. Hepatoprotective and Neurological Activities

Some reported findings validated the ethnomedicinal uses of P. indica for managing diabetic liver injury. P. indica leaf EtOH extract (doses 50 and 100 mg/kg for 2 weeks) ameliorated hyperglycemia-induced liver damage in STZ mice through the modulation of inflammatory responses and oxidative stress by inhibiting IL-6, TNF-α, TGF-β1, NF-κB p65, and PKC (protein kinase C), resulting in a reduction in hepatic apoptosis and improvement of hepatic architecture [44][101].

Another study reported that the root extract (doses 50–100 mg/kg, p.o.) remarkably prolonged pentobarbital sleep and reduced locomotor activity in isolated mice but not in group-housed mice. However, at high doses (dose 400 mg/kg, p.o.), it reduced locomotor activity and prolonged pentobarbital sleep in group-housed mice in comparison to diazepam (doses 0.1 and 0.5 mg/kg), which noticeably prolonged pentobarbital sleep in both isolated and group-housed mice. The effect of root extract and diazepam on pentobarbital sleep was significantly attenuated by flumazenil (1 mg/kg, i.v.). It suppressed the isolated mice’s aggressive behavior induced by social isolation. It was suggested that the GABAergic system was partly implicated in pentobarbital-caused sleep [21][34].

4.8. Antifertility Activity

Interestingly, P. indica has been used orally in men as an antifertility alternative medicine [28][29][45][20,21,106]. Spermiogenesis is the last phase of spermatogenesis in which spermatids are converted to spermatozoa, which play a substantial function in the fertilization process [46][107].4.9. Wound-Healing Activity

In Thai traditional medicines, P. indica leaf was used as stringent to heal wounds and ulcers [47][112]. Fibroblasts represent the major type of connective tissue cells that produce an extracellular matrix accountable for maintaining tissue structural integrity [48][49][113,114]. They have a substantial function in the wound-healing proliferative phase, causing deposition of extracellular matrix [50][115]. Over proliferation of fibroblast during wound healing leads to the production of abnormally large amounts of collagens and extracellular matrix, resulting in scar formation and functional impairment that may further trigger permanent fibrosis [51][116]. The EtOH extract of leaves that was rich in flavonoids (19.44 mg/gram) exhibited remarkable antioxidant potential (IC50 21.53 μg/mL) and had no effect on fibroblast 3T3 BALB C viability (IC50 311.776 μg/mL) in the prestoblue cytotoxicity test. This supported the use of leaf extract as a nutrient to accelerate wound healing in the oral cavity injury [47][112].

4.10. Anti-Hemorrhoidal Activity

The leaves of P. indica are traditionally utilized for treating hemorrhoids. This was supported by a study performed by Senvorasinh et al. They reported that the oral administration of hot P. indica tea H2O extract remarkably attenuated (dose 50 mg/kg/day) the rectal damage and hemorrhoids induced by croton oil in rats, as evident by no noticeable reduction in rectum and spleen weights. Conversely, it had no effect on gastrointestinal movement in mice, indicating it did not reduce constipation [52][119].

4.11. Antimicrobial Activity and Pharmaceutical Preparations

The leaf extract prohibited the growth of Streptococcus mutans, the causative organism of dental caries (MIC 10%), in the disk diffusion assay [53][54][120,121]. Further, the leaf extract toothpaste prevented dental caries in rats based on Rontgen examination results. Additionally, it reduced the virulence of mouth bacteria that initiated dental caries. Therefore, P. indica herbal toothpaste could treat caries in rat teeth [55][122]. P. indica leaf EtOH extract had inhibitory effects on C. albicans (MIC 100 mg/mL) [56][123]. Further, Alvionida et al. prepared different gel formulae using HPMC (hydroxypropyl methylcellulose) and carbopol 940. It was found that the gel formula with 1% carbopol 940 and 1.5% HPMC possessed antibacterial potential toward P. aeruginosa and S. aureus in the cup-plate diffusion assay [57][124]. Komala et al. stated that the deodorant rolls with 3 to 5% P. indica leaf extracts exhibited antibacterial potential towards S. epidermidis without causing skin irritation in both women and men. The 3% extract deodorant roll was most effective against S. epidermidis than the other formulae for removing the bad body odor [58][125], which proved its traditional use to eliminate bad odor. The leaf extract was evaluated for antibacterial potential (concentration 2.5 to 6.5%) towards E. faecalis, P. gingivalis, F. nucleatum, and S. mutans, which are accountable for root canal infections, periodontal disease, and caries. It showed significant growth inhibition towards E. faecalis (inhibition zone diameter (IZD) 12.6 mm), followed by S. mutans (IZD 12.2 mm) and P. gingivalis (IZD 12.2 mm) at a concentration of 6.5%, compared to chlorhexidine (IZDs 10.9, 11.4, and 10.6 mm, conc 2%) [59][126]. It also prohibited biofilm formation and decreased adhesion of E. faecalis and F. nucleatum in the micro-titter plate and auto-aggregation assays, respectively [60][127]. Hence, it could be utilized as an alternative to root canal sterilization dressing [60][127]. It had activity versus S. epidermidis (IZD 21.73 mm) and P. aeruginosa (IZD 21.44 mm) at 1 mg/mL [61][128]. Sittiwet suggested the possible urinary tract infection treatment potential of the aerial parts aqueous extract through its inhibitory effect on E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae [62][129]. Further, the root MeOH extract of P. indica (doses 0.5 and 1.0 mg/kg body weight) remarkably alleviated S. typhimurium caused typhoid fever in mice in vivo [63][130]. Fresh stems, roots, and twigs prohibited the growth of S. aureus, P. fluorescens, B. cereus, S. typhimurium, and E. coli, whereas fresh samples had more potent inhibitory potential than dried samples [64][131].

4.12. Antioxidant Activity

P. indica fresh leaves are used in many kinds of foods, including soups, salads, and side dishes. Additionally, leaf extracts and dried leaves are commonly consumed as food supplements and tea in Thailand. Several studies confirmed the significant antioxidant potential of various extracts of P. indica that is highly correlated to its high total phenols and flavonoids contents.