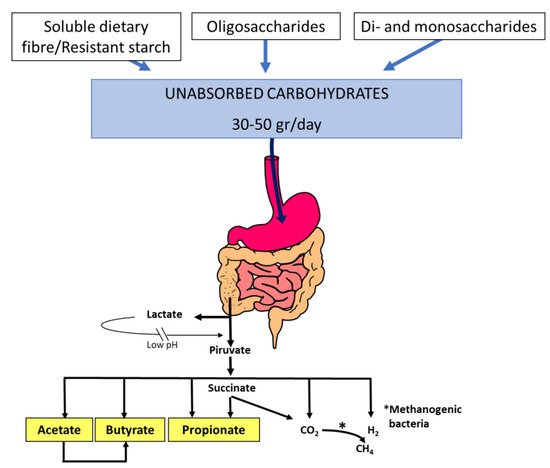

When malabsorbed carbohydrates reach the colon, they are fermented by colonic bacteria, with the production of short-chain fatty acids and gas lowering colonic pH. The appearance of diarrhoea or symptoms of flatulence depends in part on the balance between the production and elimination of these fermentation products. Different studies have shown that there are no differences in the frequency of sugar malabsorption between patients with irritable bowel disease (IBS) and healthy controls; however, the severity of symptoms after a sugar challenge is higher in patients than in controls.

- sugar malabsorption

- lactose

- fructose

- sorbitol

- sucrose

- FODMAP

- Irritable bowel syndrome

1. Introduction

2. Lactose Malabsorption and Intolerance

LM is typically caused by lactase downregulation after infancy due to lactase non-persistence, which, in Caucasians, is mediated by the LCT−13910:C/C genotype [4][7]. LM refers to an inefficient digestion of lactose in the small intestine. There are primary and secondary causes (such as viral gastroenteritis, giardiasis, and celiac disease). Lactose intolerance is the occurrence of gastrointestinal symptoms such as bloating, borborygmi, flatulence, abdominal pain, and diarrhoea in patients with LM after ingestion of lactose. The difference between LM and lactose intolerance is important since a lactose-restricted diet is only indicated in patients with both malabsorption and intolerance [5][9].

Symptoms of lactose intolerance characteristically do not arise until there is less than 50% of lactase activity. However, since adults with lactase deficiency often maintain between 10% and 30% of intestinal lactase activity, symptoms only develop when they eat enough lactose to overcome the compensatory mechanisms of the colon. There appears to be a dose-dependent effect.

HBT is the test of choice to assess LM and symptoms of intolerance [6][7][8][14,15,16]. Lactose HBT measures hydrogen produced by intestinal bacteria in the end-expiratory air after an oral challenge with a standard dose of lactose. In clinical practice, an intermediate lactose dose of 20–25 g in a 10% water solution is recommended [6][7][8][9][10,14,15,16].

3. Sucrase-Isomaltase Deficiency

4. Fructose Malabsorption

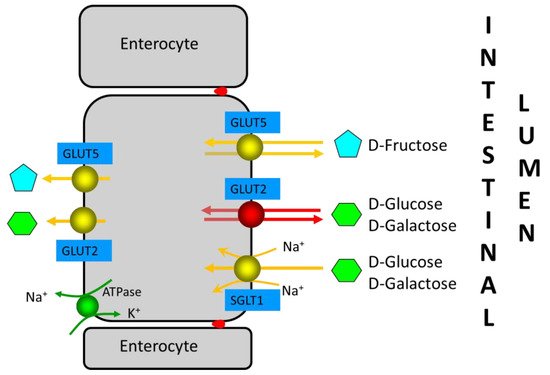

Fructose is commonly obtained from sugar beets, sugar cane, and maize and is the sweetest of all natural sugars [12][34]. Fructose can be present as a monosaccharide or as disaccharide sucrose in a one-to-one molecular ratio with glucose. In recent decades, the solubility and sweetness of fructose have been exploited by the food industry in the form of sweetener blends derived from the enzymatic conversion of starches, with the increasing popularity of the use of high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), a mixture of glucose and fructose in monosaccharide form, which may be of concern if it contains more fructose than glucose. In addition, use of fructose enhances the flavour and physical appeal of many foods and beverages. Thus, fructose is used in place of sucrose and other carbohydrates to reduce the caloric content of dietetic products while conserving high-quality sweetening profiles [13][35]. Fructose is mainly absorbed in the proximal small intestine. The absorption of monosaccharides is mainly mediated by the Na+-glucose cotransporter SGLT1 and the facilitative transporters GLUT2 and GLUT5 [14](reviewed in [1]) (Figure 2). In brief, SGLT1 and GLUT2 are important for the absorption of glucose and galactose, while the GLUT5 transporter is related to fructose absorption. SGLT1 and GLUT5 are continuously localized in the apical brush-border membrane of enterocytes, whereas GLUT2 is localized in the basolateral membrane at low luminal glucose concentrations or in both the apical brush-border membrane and the basolateral membrane at high luminal glucose concentrations. Fructose monosaccharide is transported across the apical intestinal brush-border membrane via a Na+-independent facilitated diffusion mechanism via the GLUT5 transporter. GLUT5 expression is induced by fructose, which exerts a fast and strong upregulation of GLUT5 mRNA expression, leading to an increase in GLUT5 protein and activity levels. Approximately 90% of the fructose entering the enterocyte is metabolized, increasing the intracellular pool of glucose. The remaining fructose subsequently exits the enterocytes to enter the blood via the GLUT2 and GLUT5 transporters present at the basolateral membrane. GLUT2 may be recruited transiently in the apical brush-border membrane in response to high luminal glucose concentrations to assist in the absorption of excess luminal fructose. GLUT2 is a high-capacity, low-affinity glucose/galactose transporter that can co-transport fructose in a one-to-one ratio. GLUT2 is unable to transport fructose without the presence of glucose, although the mechanism for this is currently unknown.