2. Svaneti as a Special Cultural Area in Georgia

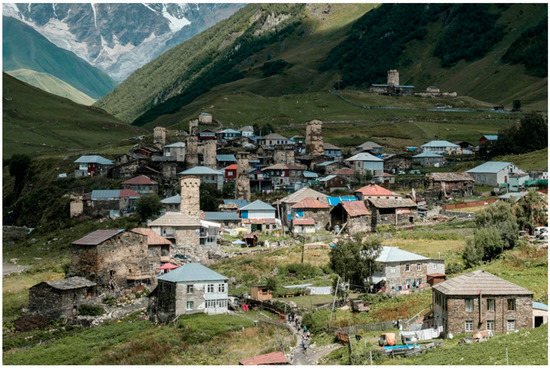

Ushguli’s value as a tourist destination lies in its defensive tower houses (see

Figure 2) and the remarkably extensive retention of its landscape’s medieval-era appearance (

Figure 3)

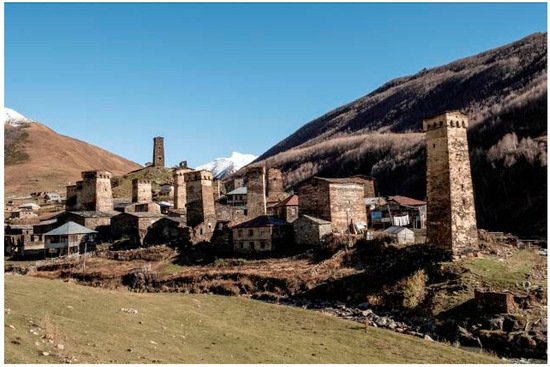

[13][14][15][15,16,17]. The area has held UNESCO World Heritage status since 1996. The settlement Chazhashi (see

Figure 3) is one of three places in Georgia to be listed as a World Heritage site. The UNESCO World Heritage List additionally names the whole of Upper Svaneti as an “exceptional” cultural landscape, but only Chazhashi holds the status itself.

Figure 2. The upper villages of Ushguli with Mount Shkhara in the background (Applis 2019).

Figure 3. View of Chazhashi, the current World Heritage site in Ushguli, which in the Soviet era was known as the Ushguli–Chazhashi Museum Reserve and has held protected status since 1971 (Applis 2018).

However, within the last years, uncoordinated building works in response to the tourist impact/influence on Ushguli have changed the community’s architectural character and the surrounding cultural landscape, producing discrepancies between UNESCO’s justification for awarding World Heritage status and the current situation in the region (

Figure 4)

[16][17][18,19]. It is possible that UNESCO could, as it has in other cases, diminish the geographical extent of Georgia’s World Heritage sites or remove the status from an entire architectural ensemble. In the meantime, this risk is also under discussion in Georgia

[18][19][20,21]. Observers and the local population fear that a withdrawal of the World Heritage status could decrease the number of tourists and the chances of the mountain region catching up with its development

[20][21][22,23].

Figure 4. Different ways of constructing tourist space: (a) newly built hotel in European Alpine style (Applis 2019); (b) simple garden café in front of a 1950s Soviet-era building (Applis 2015).

Even in the Soviet era, Svaneti was known for the substantial ethnic homogeneity of its population and distinct conceptions of community and legal precepts, as is typical of some of the mountainous regions of the Caucasus

[22][23][24][24,25,26]. This homogeneity derives from the population’s subsistence from agriculture at an altitude of 1500–2500 m and the resulting need for a collective lifeworld and long-term maintenance of strong identification with a shared origin and heritage. A concomitant issue is that the population has a clearly defined idea of their own identity and a distinct delimitation from neighboring groups

[25][27].

From the early Soviet-era onwards, the region found itself the target of specific cultural interventions, typical for Soviet policy around nationality and national identities

[26][28] (pp. 90ff.) about the relationship between the state and traditional law in Soviet times. However, Svaneti remained an exemplary region for limitations of measures that were intended to bring about cultural transformation. The Soviet authorities finally failed in their endeavors to break up local notions and institutions of law, such as councils of elders. Even in Soviet times, these councils intermediated in the arrangement of marriage, issues relating to the distribution of land and attempts to quell vendettas

[22][24]. Even current studies suggest a continued high acceptance of such practices. They also indicate that non-Svan ethnic Georgians regard the country’s mountain people as possessing an authentic core of ethnonational “Georgianness”, inextricably linked to Georgian Orthodox Christianity

[27][29].

3. General Challenges for Tourism Development in the Svaneti Region as Exemplified by the Village Community of Ushguli

There are numerous recent publications on Ushguli that have engaged with the region’s challenges. Most

resea

rcheuthors emphasize the necessity of economically and socially sustainable approaches and highlight the risk to the location’s architectural heritage by human activity and natural events such as avalanches and land- and mudslides

[28][29][30][31][32][33][34][30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. However, almost all these studies emerged from relatively brief stays by the relevant research groups, recording primarily quantitative data or collecting fairly straightforward qualitative material, such as short interviews. Consequently, they tend to focus on the general information of factors common to sustainable agritourism activities. However, there is an overall consensus that the specific social conditions that characterize Ushguli would prevent the success of any management plan imposed from outside. It would take years for stakeholders to gain awareness of the developments and shifts that ensue when numbers of tourists swell. Mosedalee

[35][37] (p. 60) emphasized that “more in-depth research is necessary that analyses (a) the meanings of hospitality in a neoliberal political economy and changes to local cultures (in particular values of ‘giving’ hospitality), (b) the distinct entrepreneurial cultures emerging from new institutional and political-economic constellations and (c) the ‘new landscape of governance’, particularly as different actors and levels of scale become involved.”

Svaneti was more or less closed to researchers from parts of the world that were not part of the Soviet system until well into the 1990s. The region was also closed to tourists from Eastern Europe. Georgia’s accession to Europe and the USA after the civil war turmoil of the 1990s quickly opened Georgia to English-speaking researchers, as evidenced by the literature cited above. However, both Georgian and Russian as lingua franca are mostly not widely spoken by these researchers. Therefore, these studies rather test general theses on the development of peripheral regions using the example of Georgia’s mountain regions and present correspondingly general results.

However, Svaneti is a special case for various reasons explained in this

resear

chticle, which is why no meaningful qualitative data can be collected without appropriate language skills and without research designed for a longer period of time with long stays in the field. The qualitative data collected are accordingly not quantifiable. It is also questionable whether the social practices and phenomena described here are transferable to other peripheral regions on which several contributions are available (e.g.,

[36][37][38][39][40][38,39,40,41,42]). This is because traditionally shaped livelihoods unfold in culturally specific ways in the regions studied, where tourism is seen as a way of overcoming poverty. Comparing the available results would be a research goal in itself. This transfer cannot be undertaken here in a scientifically serious manner without visiting the corresponding regions.

Svaneti had only poorly developed mountaineering tourism during the Soviet era. This focused on the high peaks of the Great Caucasus and attracted mainly Soviet athletes. The Svans as an ethnic group thus had hardly any contact with tourists until well into the 2000s. During the Soviet period, Svaneti was considered a difficult region to control as explained above, despite intensive attempts to Sovietize it. The patriarchal structures of the communities there persisted, and collectivization was carried out only superficially. In fact, even Soviet law was only partially implemented there; de facto law continued to be pronounced in the communities by so-called councils of elders

[22][26][24,28]. After the civil war in Georgia, Svaneti was a de facto lawless area for a long time; only in the early 2000s, the government there succeeded in defeating clan criminality and establishing security for the population.

The society of Svaneti has been confronted with multiple processes of globalization in the context of tourism development for about ten years now, of which the digitalization of travel in the form of online bookings and comments on stays is only one. Serious qualitative research in the mountain regions of Georgia must therefore overcome the following challenges: it must master linguistic thresholds and build long-term trust within fragile social communities in order to obtain reliable statements about the very specific challenges of the respective communities. Implementing these demands is the goal of the approach presented here. Therefore, in the following, reference is made to contributions by researchers from Georgia; the limitations of the older contributions to Svaneti, briefly outlined above, have been discussed elsewhere

[16][18].

4. Effects of Over-Shaping the Livelihoods of Mountain Populations in Georgia

In recent years, Georgian researchers have pointed out that tourism in the previously relatively remote regions of the country also has adverse effects on social and economic livelihoods

[2][28][41][2,30,43]. So far, only one study has been published that explicitly addressed the change in mountain livelihoods under the influence of tourism and examined the types of change. The

resea

rcheuthors, like other researchers, set the preservation of the mountain farming cultural landscape as the norm. They used the examples of Mestia in Svaneti and Kazbegi in the Mtskheta-Mtianeti region to investigate why exactly tourism in the mountains of Georgia is causing a decline in agriculture. The

researcheauthors identified “4 types of tourism-led livelihood change: (1) expanding non-agricultural activities; (2) reducing agricultural activities; (3) developing agritourism activities and (4) increasing agricultural activities.”

[42][44] (p. 27). Types 1 and 2 dominate and cause a massive decline in agricultural activities. This is because permanent residents of the mountain regions are too short of human, financial, technical and time resources to serve agriculture and tourism, and tourism work is less arduous. In contrast, the people who only stay in the region during the summer for the tourist season have less experience with agriculture and are more accustomed to urban lifestyles. In general, tourism causes intense competition between village communities because those who switch partly to accommodating guests soon depend on the income from overnight stays. Therefore, many

resea

rcheuthors recommend integrating tourism and community development practices, developing specific guidelines for community-based tourism projects and filling the knowledge gap of community development facilitators on tourism practices

[28][43][44][30,45,46]. In the case of the South Caucasus, the following definition of CBT is proposed: “CBT in the South Caucasus is a community development practice for nonurban and remote mountain villages. It is a joint effort of a group of people living in a certain geographical area, in which local culture, environment, and hospitality are the main advantages. CBT focuses on the benefits for the local people, capacity building, and empowerment and should constitute a core component of tourism activities in rural mountain regions”

[44][46] (p. 20).

Great hopes for sustainable tourism are intimately connected with accommodation in permanently inhabited family houses, a kind of mixture of farm holidays and hiking as well as ecotourism. This is because the inhabitants who live in Ushguli all year round guarantee the preservation of the cultural landscape. Without them, there would be no horses, cows or pigs on-site, the pastures would not be mown, and there would not be the typical food that visitors can enjoy. The old stone buildings could hardly be preserved, and within a short time, there would be even more waste because the small farms would fall into disrepair, and no one would produce the food consumed locally (

[19][21], p. 118, with reference to

[17][21][19,23]).

If the hopes for development through tourism are to be fulfilled, especially in peripheral regions, strong and independent institutional support is needed for regional communities in which their own resources for regulating processes are not or no longer available. In Ushguli, the crisis experiences of the 1980s and 1990s can be considered the cause of the lack of these self-regulatory capacities.