Delivering therapeutics to the central nervous system (CNS) is difficult because of the blood–brain barrier (BBB). Therapeutic delivery across the tight junctions of the BBB can be achieved through various endogenous transportation mechanisms. Receptor-mediated transcytosis (RMT) is one of the most widely investigated and used methods. Drugs can hijack RMT by expressing specific ligands that bind to receptors mediating transcytosis, such as the transferrin receptor (TfR), low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR), and insulin receptor (INSR). Cell-penetrating peptides and viral components originating from neurotropic viruses can also be utilized for the efficient BBB crossing of therapeutics. Exosomes, or small extracellular vesicles, have gained attention as natural nanoparticles for treating CNS diseases, owing to their potential for natural BBB crossing and broad surface engineering capability. RMT-mediated transport of exosomes expressing ligands such as LDLR-targeting apolipoprotein B has shown promising results.

- exosome

- brain delivery

- BBB crossing

- transcytosis

1. Introduction

2. Current Strategies for Delivering Therapeutics across the BBB

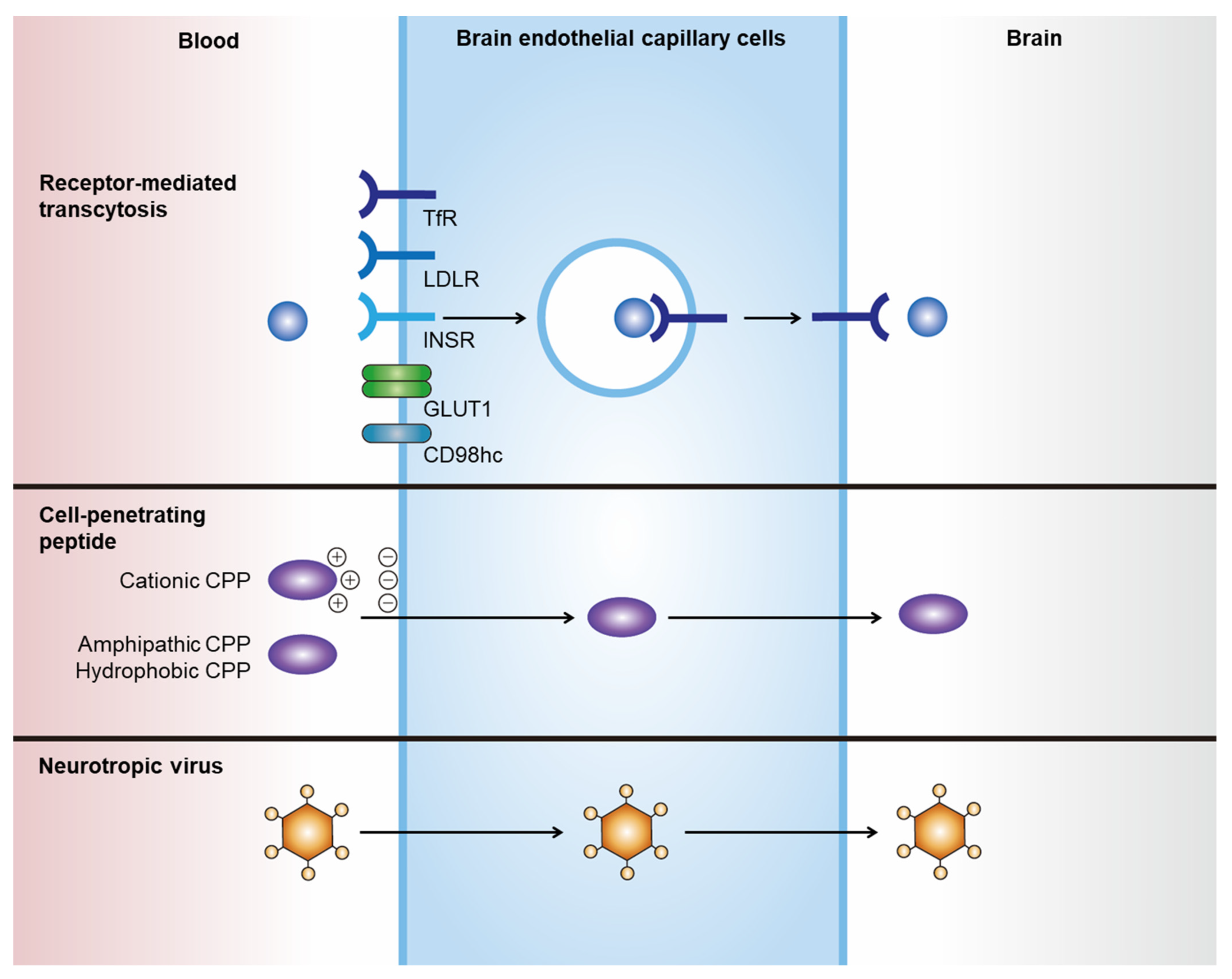

Noninvasive delivery of therapeutics to the CNS can be achieved by hijacking endogenous transport pathways, such as receptor-mediated transcytosis (RMT) and adsorptive-mediated transcytosis (Figure 1, Table 1) [11,12][11][12]. Among these, RMT has been the most investigated and applied route for the transportation of drugs through endothelial cells of the BBB [13]. Various therapeutics, including chemicals, antibodies, polymeric nanoparticles, and exosomes, can incorporate these strategies. Their efficacy in brain delivery has been actively tested in numerous preclinical studies and clinical trials [11].

| BBB Crossing Strategies | Summary |

|---|---|

| Receptor-mediated transcytosis |

|

| Cell-penetrating peptides |

|

| Neurotropic virus |

|

2.1. Receptor-Mediated Transcytosis

Transcytosis is the vesicular crossing of macromolecules from one side of the cell membrane to another [14]. RMT is mediated by the binding of a ligand to a specific receptor, which subsequently induces receptor-mediated endocytosis and further transports invaginated endosomal compartments to the other side of the membrane. Drugs can hijack RMT by expressing specific ligands that bind to receptors that mediate transcytosis. The optimal receptors to be utilized for RMT-mediated BBB crossing are highly and locally expressed on the membrane of brain capillary endothelial cells (BCECs), with low expression on peripheral endothelial cells. However, to date, no ideal receptor has been identified. Nevertheless, highly and ubiquitously expressed receptors on BCECs have shown promising results in RMT-mediated brain delivery in preclinical studies and several clinical trials.2.2. Cell-Penetrating Peptides

Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs), or protein transduction domains, are a family of short peptides (<30 amino acids) that can induce the translocation of biologically active macromolecules across cell membranes without interacting with specific receptors [15,16][15][16]. Although no consensus has been reached regarding the taxonomy of CPPs, they can generally be categorized into three classes based on their physicochemical properties: cationic, amphipathic, and hydrophobic [15]. The cationic class is mainly composed of peptides with positive charges, such as arginine and lysine, that can interact with negatively charged plasma membranes. The transactivator of transcription (TAT) protein of HIV-1 was the first CPP observed to be internalized into cells in vitro in 1988 [67[17][18],68], and it has since been widely investigated as an inducer of intracellular delivery of therapeutics. Amphipathic CPPs are the most commonly found CPPs in nature, and they contain polar and nonpolar amino acid regions [16]. Hydrophobic CPPs contain nonpolar hydrophobic residues that induce cell penetration by interacting with the hydrophobic domains of plasma membranes. The apical surface of cerebral capillaries is densely covered with a negatively charged glycocalyx, which renders positively charged CPPs an efficient transporter of drugs through the BBB [69][19]. However, several issues must be addressed when using CPPs for brain delivery, such as their low tissue specificity and cellular toxicity. CPP-conjugated drugs show widespread biodistribution owing to their lack of tissue specificity. In addition, the cytotoxicity of CPPs is a major concern [70][20], as shown in the case of amphipathic CPP model amphipathic peptide, which induces damage to the cellular membrane, resulting in the leakage of cellular components and subsequent cell death [71][21].2.3. Neurotropic Virus

Neurotropic viruses can cross the BBB and invade the brain parenchyma, which prompted the investigation of viruses or viral components as transporters for the brain delivery of therapeutics. For instance, peptides derived from rabies virus glycoprotein (RVG) exhibit efficient penetration through the BBB and target neurons [72][22]. Although the exact BBB crossing mechanism is unknown, it is expected to occur via neuronal acetylcholine receptor-mediated RMT [72][22]. RVG has been utilized for the delivery of various nanoparticles through the BBB, including liposomes [73][23], layered double hydroxide [74][24], porous silicon nanoparticles [75][25], and exosomes [76][26]. However, its biological safety and efficacy should be investigated in preclinical studies for clinical translation.3. Targeted Delivery of Exosomes to the Brain

3.1. Natural Brain Delivery of Exosomes to the Brain

Unmodified exosomes from various cell types show <1% delivery to the brain after systemic injection [77[27][28],78], implying that exosomes have a natural tendency to bypass the BBB. Although the exact mechanism by which naïve exosomes cross the BBB is unknown. Recent studies have shown that exosomes originating from different parental cells have different organ and tissue tropisms [77,79,80,81][27][29][30][31]. Moreover, the specific membrane proteins or molecules of exosomes responsible for the inclination towards specific organs are not fully known. Transport across the BBB is enhanced under specific pathological conditions. In mice exhibiting brain inflammation, macrophage-derived exosomes showed over three-fold increased delivery to the brain compared to those in normal mice [84][32]. Enhanced brain delivery is achieved through the interaction of lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1, intercellular adhesion molecule 1, and C-type lectin receptors expressed on macrophage exosomes with BCECs [84][32]. In an in vitro transwell assay, unmodified naïve exosomes demonstrated enhanced endocytosis and subsequent crossing through BCECs in a tumor necrosis factor-α-induced stroke-like inflammation model [85][33]. As unmodified exosomes exhibit potential for brain delivery without additional modifications, their efficacy for BBB crossing should be further validated in preclinical studies.3.2. Brain Delivery of Engineered Exosomes by Receptor-Mediated Transcytosis

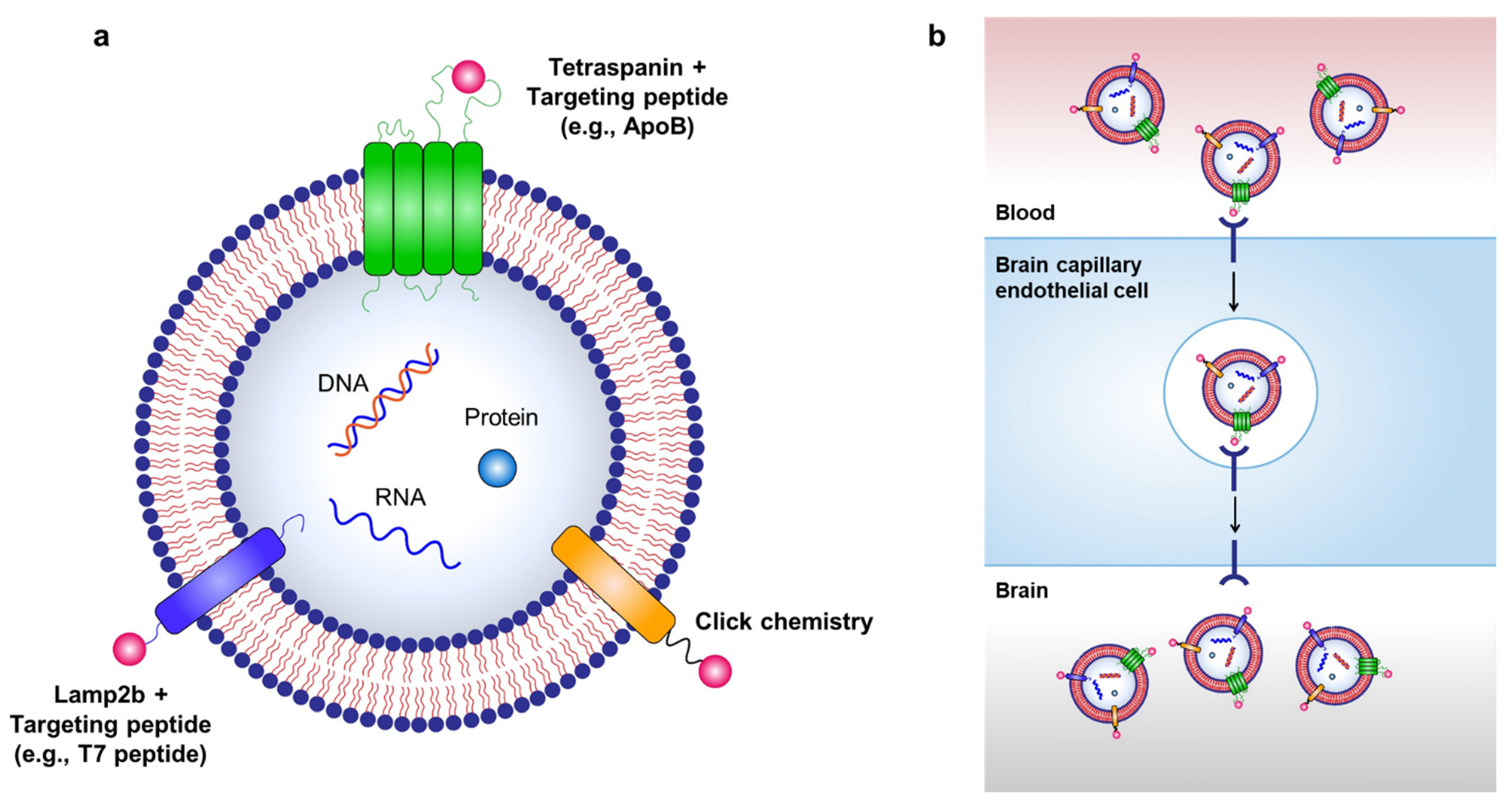

Targeted delivery of exosomes to the brain can be achieved through various exosome surface modifications (Figure 2). As hijacking RMT is a widely used strategy for delivering therapeutics across the BBB, it can also be used for transporting exosomes to the brain via labeling of targeting peptides on the surface of exosomes. For example, Kim et al. used a T7 peptide for the delivery of exosomes (T7-exo) [86][34]. T7 peptide is a TfR-binding peptide with the sequence HAIYPRH, which does not disturb the binding of transferrin to TfR [87,88][35][36]. By conjugating T7 peptide to Lamp2b, T7-exo demonstrated superior targeting of intracranial glioblastoma in rat models after intravenous injection compared to unmodified exosomes or RVG-labeled exosomes [86][34].3.3. Other Strategies for Brain Delivery

Targeted delivery of exosomes to the brain can be achieved through various exosome surface modifications (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Strategies for targeted delivery of therapeutic exosomes to the brain. (a) Targeted delivery of exosomes to the brain can be achieved by labeling various targeting moieties on the surface of exosomes. Therapeutic exosomes can be engineered to express various targeting moieties via chemical modifications, such as click chemistry, or via genetic modification of exosome-producing cells to express targeting peptides fused with exosomal membrane-associated components, such as Lamp2b and tetraspanins. (b) RMT can be used to transport exosomes to the brain via labeling of targeting peptides on the surface of exosomes.

Neurotropic virus-derived peptides, such as RVG, have been used to induce brain-targeting of exosomes in several preclinical studies. In one study, brain delivery of siRNA-loaded exosomes was achieved by expressing RVG at the exosomal membrane and fusing it with Lamp2b, an exosomal membrane protein [76][26]. The exact BBB crossing pathway has not been shown; however, modified exosomes demonstrated efficient delivery of siRNA to neurons, microglia, and oligodendrocytes in mouse brain [76][26]. In another study, the same group used a similar approach to deliver siRNA for α-synuclein (α-Syn) to the brain of α-syn transgenic mice [92][37]. Further studies are needed to identify safety issues associated with the use of virus-derived peptides as therapeutic agents. Peptides that bind to specific membrane proteins can also be used for exosome modification. For example, c(RGDyK) peptide, which binds to integrin αvβ3 that is highly expressed in BCECs under ischemic conditions, was labeled on the surface of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes through click chemistry [93][38]. Click chemistry, also known as copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition, is an efficient covalent reaction of an alkyne and an azide residue to form a stable triazole linkage, and can be applied to attach various targeting moieties to the surface of exosomes [94,95,96,97,98][39][40][41][42][43]. c(RGDyK) peptide-labeled exosomes exhibited 11-fold enhanced delivery to the ischemic region of the brain compared with scrambled peptide-labeled exosomes in a mouse stroke model [93][38].4. Conclusions

Exosomes are gaining attention because of their potential as next-generation nanoparticles for treating CNS diseases owing to their potential for natural BBB crossing and broad surface-engineering capability. Various technologies to efficiently incorporate drugs and active pharmaceutical ingredients into exosomes are being actively developed [4,99,100][4][44][45]. In addition, various preclinical studies have investigated engineering strategies for targeted delivery of exosomes to specific organs and tissues [101][46]. Exosomes carry various membrane proteins (e.g., CD9 [102][47], CD63 [103][48], PTGFRN [104][49], and Lamp2b [76][26]) and lipids (e.g., phosphatidylserine [105][50]) that can be utilized for the surface engineering of various targeting moieties. Engineered exosomes possessing targetability to the brain have shown promising results for CNS delivery in preclinical studies; however, they also require intense evaluation through well-designed clinical trials. For the successful development of clinically approved exosome therapeutics for CNS diseases, the establishment of imaging methods for quantitative/qualitative monitoring of exosomal delivery to the brain parenchyma in vivo and uncovering the detailed BBB crossing mechanisms of exosomes is needed.References

- Lipinski, C.A.; Lombardo, F.; Dominy, B.W.; Feeney, P.J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 46, 3–26.

- Pegtel, D.M.; Gould, S.J. Exosomes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2019, 88, 487–514.

- Yang, D.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, F.; Chen, L.; Ma, L.; Larcher, L.M.; Chen, S.; Liu, N.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Progress, opportunity, and perspective on exosome isolation—efforts for efficient exosome-based theranostics. Theranostics 2020, 10, 3684–3707.

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020, 367, eaau6977.

- Escudier, B.; Dorval, T.; Chaput, N.; Andre, F.; Caby, M.P.; Novault, S.; Flament, C.; Leboulaire, C.; Borg, C.; Amigorena, S.; et al. Vaccination of metastatic melanoma patients with autologous dendritic cell (DC) derived-exosomes: Results of thefirst phase I clinical trial. J. Transl. Med. 2005, 3, 10.

- Lai, R.C.; Arslan, F.; Lee, M.M.; Sze, N.S.; Choo, A.; Chen, T.S.; Salto-Tellez, M.; Timmers, L.; Lee, C.N.; El Oakley, R.M.; et al. Exosome secreted by MSC reduces myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Stem Cell Res. 2010, 4, 214–222.

- Nikfarjam, S.; Rezaie, J.; Kashanchi, F.; Jafari, R. Dexosomes as a cell-free vaccine for cancer immunotherapy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 39, 258.

- Babaei, M.; Rezaie, J. Application of stem cell-derived exosomes in ischemic diseases: Opportunity and limitations. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 196.

- Ahmadi, M.; Rezaie, J. Ageing and mesenchymal stem cells derived exosomes: Molecular insight and challenges. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2021, 39, 60–66.

- Nam, G.H.; Choi, Y.; Kim, G.B.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.A.; Kim, I.S. Emerging Prospects of Exosomes for Cancer Treatment: From Conventional Therapy to Immunotherapy. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e2002440.

- Terstappen, G.C.; Meyer, A.H.; Bell, R.D.; Zhang, W. Strategies for delivering therapeutics across the blood-brain barrier. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 362–383.

- Azarmi, M.; Maleki, H.; Nikkam, N.; Malekinejad, H. Transcellular brain drug delivery: A review on recent advancements. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 586, 119582.

- Pulgar, V.M. Transcytosis to Cross the Blood Brain Barrier, New Advancements and Challenges. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 1019.

- Tuma, P.; Hubbard, A.L. Transcytosis: Crossing cellular barriers. Physiol. Rev. 2003, 83, 871–932.

- Guidotti, G.; Brambilla, L.; Rossi, D. Cell-Penetrating Peptides: From Basic Research to Clinics. Trends Pharmcol. Sci. 2017, 38, 406–424.

- Xie, J.; Bi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Dong, S.; Teng, L.; Lee, R.J.; Yang, Z. Cell-Penetrating Peptides in Diagnosis and Treatment of Human Diseases: From Preclinical Research to Clinical Application. Front. Pharmcol. 2020, 11, 697.

- Frankel, A.D.; Pabo, C.O. Cellular uptake of the tat protein from human immunodeficiency virus. Cell 1988, 55, 1189–1193.

- Green, M.; Loewenstein, P.M. Autonomous functional domains of chemically synthesized human immunodeficiency virus tat trans-activator protein. Cell 1988, 55, 1179–1188.

- Ando, Y.; Okada, H.; Takemura, G.; Suzuki, K.; Takada, C.; Tomita, H.; Zaikokuji, R.; Hotta, Y.; Miyazaki, N.; Yano, H.; et al. Brain-Specific Ultrastructure of Capillary Endothelial Glycocalyx and Its Possible Contribution for Blood Brain Barrier. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17523.

- Saar, K.; Lindgren, M.; Hansen, M.; Eiriksdottir, E.; Jiang, Y.; Rosenthal-Aizman, K.; Sassian, M.; Langel, U. Cell-penetrating peptides: A comparative membrane toxicity study. Anal. Biochem. 2005, 345, 55–65.

- Moutal, A.; Francois-Moutal, L.; Brittain, J.M.; Khanna, M.; Khanna, R. Differential neuroprotective potential of CRMP2 peptide aptamers conjugated to cationic, hydrophobic, and amphipathic cell penetrating peptides. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2014, 8, 471.

- Wang, Q.; Cheng, S.; Qin, F.; Fu, A.; Fu, C. Application progress of RVG peptides to facilitate the delivery of therapeutic agents into the central nervous system. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 8505–8515.

- Dos Santos Rodrigues, B.; Arora, S.; Kanekiyo, T.; Singh, J. Efficient neuronal targeting and transfection using RVG and transferrin-conjugated liposomes. Brain Res. 2020, 1734, 146738.

- Chen, W.; Zuo, H.; Zhang, E.; Li, L.; Henrich-Noack, P.; Cooper, H.; Qian, Y.; Xu, Z.P. Brain Targeting Delivery Facilitated by Ligand-Functionalized Layered Double Hydroxide Nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 20326–20333.

- Kang, J.; Joo, J.; Kwon, E.J.; Skalak, M.; Hussain, S.; She, Z.G.; Ruoslahti, E.; Bhatia, S.N.; Sailor, M.J. Self-Sealing Porous Silicon-Calcium Silicate Core-Shell Nanoparticles for Targeted siRNA Delivery to the Injured Brain. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 7962–7969.

- Alvarez-Erviti, L.; Seow, Y.; Yin, H.; Betts, C.; Lakhal, S.; Wood, M.J. Delivery of siRNA to the mouse brain by systemic injection of targeted exosomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 341–345.

- Wiklander, O.P.; Nordin, J.Z.; O’Loughlin, A.; Gustafsson, Y.; Corso, G.; Mager, I.; Vader, P.; Lee, Y.; Sork, H.; Seow, Y.; et al. Extracellular vesicle in vivo biodistribution is determined by cell source, route of administration and targeting. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 26316.

- Mirzaaghasi, A.; Han, Y.; Ahn, S.H.; Choi, C.; Park, J.H. Biodistribution and Pharmacokinectics of Liposomes and Exosomes in a Mouse Model of Sepsis. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 427.

- Sancho-Albero, M.; Navascues, N.; Mendoza, G.; Sebastian, V.; Arruebo, M.; Martin-Duque, P.; Santamaria, J. Exosome origin determines cell targeting and the transfer of therapeutic nanoparticles towards target cells. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2019, 17, 16.

- Qiao, L.; Hu, S.; Huang, K.; Su, T.; Li, Z.; Vandergriff, A.; Cores, J.; Dinh, P.U.; Allen, T.; Shen, D.; et al. Tumor cell-derived exosomes home to their cells of origin and can be used as Trojan horses to deliver cancer drugs. Theranostics 2020, 10, 3474–3487.

- Smyth, T.; Kullberg, M.; Malik, N.; Smith-Jones, P.; Graner, M.W.; Anchordoquy, T.J. Biodistribution and delivery efficiency of unmodified tumor-derived exosomes. J. Control. Release 2015, 199, 145–155.

- Yuan, D.; Zhao, Y.; Banks, W.A.; Bullock, K.M.; Haney, M.; Batrakova, E.; Kabanov, A.V. Macrophage exosomes as natural nanocarriers for protein delivery to inflamed brain. Biomaterials 2017, 142, 1–12.

- Chen, C.C.; Liu, L.N.; Ma, F.X.; Wong, C.W.; Guo, X.N.E.; Chacko, J.V.; Farhoodi, H.P.; Zhang, S.X.; Zimak, J.; Segaliny, A.; et al. Elucidation of Exosome Migration Across the Blood-Brain Barrier Model In Vitro. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 2016, 9, 509–529.

- Kim, G.; Kim, M.; Lee, Y.; Byun, J.W.; Hwang, D.W.; Lee, M. Systemic delivery of microRNA-21 antisense oligonucleotides to the brain using T7-peptide decorated exosomes. J. Control. Release 2020, 317, 273–281.

- Lee, J.H.; Engler, J.A.; Collawn, J.F.; Moore, B.A. Receptor mediated uptake of peptides that bind the human transferrin receptor. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001, 268, 2004–2012.

- Han, L.; Huang, R.; Liu, S.; Huang, S.; Jiang, C. Peptide-conjugated PAMAM for targeted doxorubicin delivery to transferrin receptor overexpressed tumors. Mol. Pharm. 2010, 7, 2156–2165.

- Cooper, J.M.; Wiklander, P.B.; Nordin, J.Z.; Al-Shawi, R.; Wood, M.J.; Vithlani, M.; Schapira, A.H.; Simons, J.P.; El-Andaloussi, S.; Alvarez-Erviti, L. Systemic exosomal siRNA delivery reduced alpha-synuclein aggregates in brains of transgenic mice. Mov. Disord. 2014, 29, 1476–1485.

- Tian, T.; Zhang, H.X.; He, C.P.; Fan, S.; Zhu, Y.L.; Qi, C.; Huang, N.P.; Xiao, Z.D.; Lu, Z.H.; Tannous, B.A.; et al. Surface functionalized exosomes as targeted drug delivery vehicles for cerebral ischemia therapy. Biomaterials 2018, 150, 137–149.

- Smyth, T.; Petrova, K.; Payton, N.M.; Persaud, I.; Redzic, J.S.; Graner, M.W.; Smith-Jones, P.; Anchordoquy, T.J. Surface functionalization of exosomes using click chemistry. Bioconjug. Chem. 2014, 25, 1777–1784.

- Ramasubramanian, L.; Kumar, P.; Wang, A. Engineering Extracellular Vesicles as Nanotherapeutics for Regenerative Medicine. Biomolecules 2019, 10, 48.

- Algar, W.R.; Prasuhn, D.E.; Stewart, M.H.; Jennings, T.L.; Blanco-Canosa, J.B.; Dawson, P.E.; Medintz, I.L. The controlled display of biomolecules on nanoparticles: A challenge suited to bioorthogonal chemistry. Bioconjug. Chem. 2011, 22, 825–858.

- Villata, S.; Canta, M.; Cauda, V. EVs and Bioengineering: From Cellular Products to Engineered Nanomachines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6048.

- Nwe, K.; Brechbiel, M.W. Growing applications of “click chemistry” for bioconjugation in contemporary biomedical research. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2009, 24, 289–302.

- Song, Y.; Kim, Y.; Ha, S.; Sheller-Miller, S.; Yoo, J.; Choi, C.; Park, C.H. The emerging role of exosomes as novel therapeutics: Biology, technologies, clinical applications, and the next. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2021, 85, e13329.

- Herrmann, I.K.; Wood, M.J.A.; Fuhrmann, G. Extracellular vesicles as a next-generation drug delivery platform. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 748–759.

- Choi, H.; Choi, Y.; Yim, H.Y.; Mirzaaghasi, A.; Yoo, J.K.; Choi, C. Biodistribution of Exosomes and Engineering Strategies for Targeted Delivery of Therapeutic Exosomes. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2021, 18, 499–511.

- Yim, N.; Ryu, S.W.; Choi, K.; Lee, K.R.; Lee, S.; Choi, H.; Kim, J.; Shaker, M.R.; Sun, W.; Park, J.H.; et al. Exosome engineering for efficient intracellular delivery of soluble proteins using optically reversible protein-protein interaction module. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12277.

- Stickney, Z.; Losacco, J.; McDevitt, S.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, B. Development of exosome surface display technology in living human cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 472, 53–59.

- Dooley, K.; McConnell, R.E.; Xu, K.; Lewis, N.D.; Haupt, S.; Youniss, M.R.; Martin, S.; Sia, C.L.; McCoy, C.; Moniz, R.J.; et al. A versatile platform for generating engineered extracellular vesicles with defined therapeutic properties. Mol. Ther. 2021, 29, 1729–1743.

- Skotland, T.; Hessvik, N.P.; Sandvig, K.; Llorente, A. Exosomal lipid composition and the role of ether lipids and phosphoinositides in exosome biology. J. Lipid Res. 2019, 60, 9–18.