1. Introduction

Strategic innovation and process optimization form changes in various aspects of organizations

[1]. Business management is experiencing growing demand in dealing with human or social sustainability for human resource preservation, support, and professional development. Companies need to take more care of organizational identity, dematerialization, and collaboration

[2] which would allow employees to commit to innovative cultures

[3]. Organizational transformations affect personal motivation, self-realization, and identity perception

[4][5]; therefore, concentration on otherwise-oriented work values creates increased engagement in change

[6] and maintains long-term loyalty.

Whenever there is a level or degree of organizational change, for some employees or employers, the change becomes a success or failure

[1]. The COVID-19 pandemic was an example of an unexpected critical issue

[6][7][8] that organizations faced, and which required them to transform usual work standards into digital environments ensuring health, safety, and business contingency. Such transitions affected the psychological resistance of some workers, as well as had other negative impacts on their social environments, professional relationships, and job satisfaction

[8][9]. Such transformations were emotionally charged by inner experiences, which led to misunderstandings, conflicts, and damaged feelings including spiritual pain

[9][10][11]. Tensions and insecurities were particularly exacerbated by the increased risk of redundancies

[11][12][13], and this forced managers to be more sensitive to employee experiences and behavior

[14]. However, the literature shows that when performing reorganizations, the problems stem from a lack of managers’ adequate knowledge, competence in the field of change management, and communication with employees, including the limited flexibility of the human factor

[15]. One of the main challenges is bridging the gap between employees and management for workplace innovation

[3], reconsidering practices, and acquiring new capabilities for the efficient facilitation of change

[16][17].

There are studies on the development of executive leadership in change management

[2][18][19][20], but notably, the phenomenon of middle management growth during organizational change is not addressed in the existing research. This research gap appears in terms of the professional development of middle managers, not as key decision makers

[16], but rather as mediators coordinating strategic initiatives and navigating employee activities towards their transformations

[17]. This research should help to understand the phenomenon of managerial growth in the context of organizational change by answering the following question: In the challenging transitional environment and within the directions of self-development, what is the role of middle managers in helping themselves and their subordinates to meet strategic organizational requirements, maintain healthy workplaces, and sustain individual wellbeing?

The novelty of this research is in its intention to explore organizational change as an incentive for personal and professional growth, emphasizing not only management but also psychological and educational contexts. The concept of “growth” in this entry is understood as a conscious, self-directed learning process that leads to the holistic and harmonious development of personality. Hiemstra and Brockett

[21] stress the importance of personal responsibility for growth, outlining the optimal situation for self-directed learning which is most effective when the person, process, and context are in balance.

Summing up, the main research question is: What are the contexts, objectives, and directions for managerial growth in organizational change? A theory synthesis and a conceptual model were applied in this research. Six theoretical approaches from the fields of management, psychology, and education (Hiatt, Kotter, Kübler-Ross, Goleman, Mezirow, Marcia) were chosen for this analysis which tackles key variables associated with the focal phenomenon: change management, relationship navigation, and subjective coping experiences. This research complements the knowledge of sustainable change management theory, organizational psychology, and andragogy in general, proposing a holistic and integrated approach to adult self-development while providing a theoretical framework for personal and professional managerial growth in the challenging context of organizational change.

Its practical value is based on its potential use as a source of recommended material for middle managers, executives, or HR personnel, allowing them to understand the context of change from a holistic perspective and providing training on related topics for sustainable and growing workplace environments.

2. CuIntegrrent Insigated Approach to Managerial Growthts

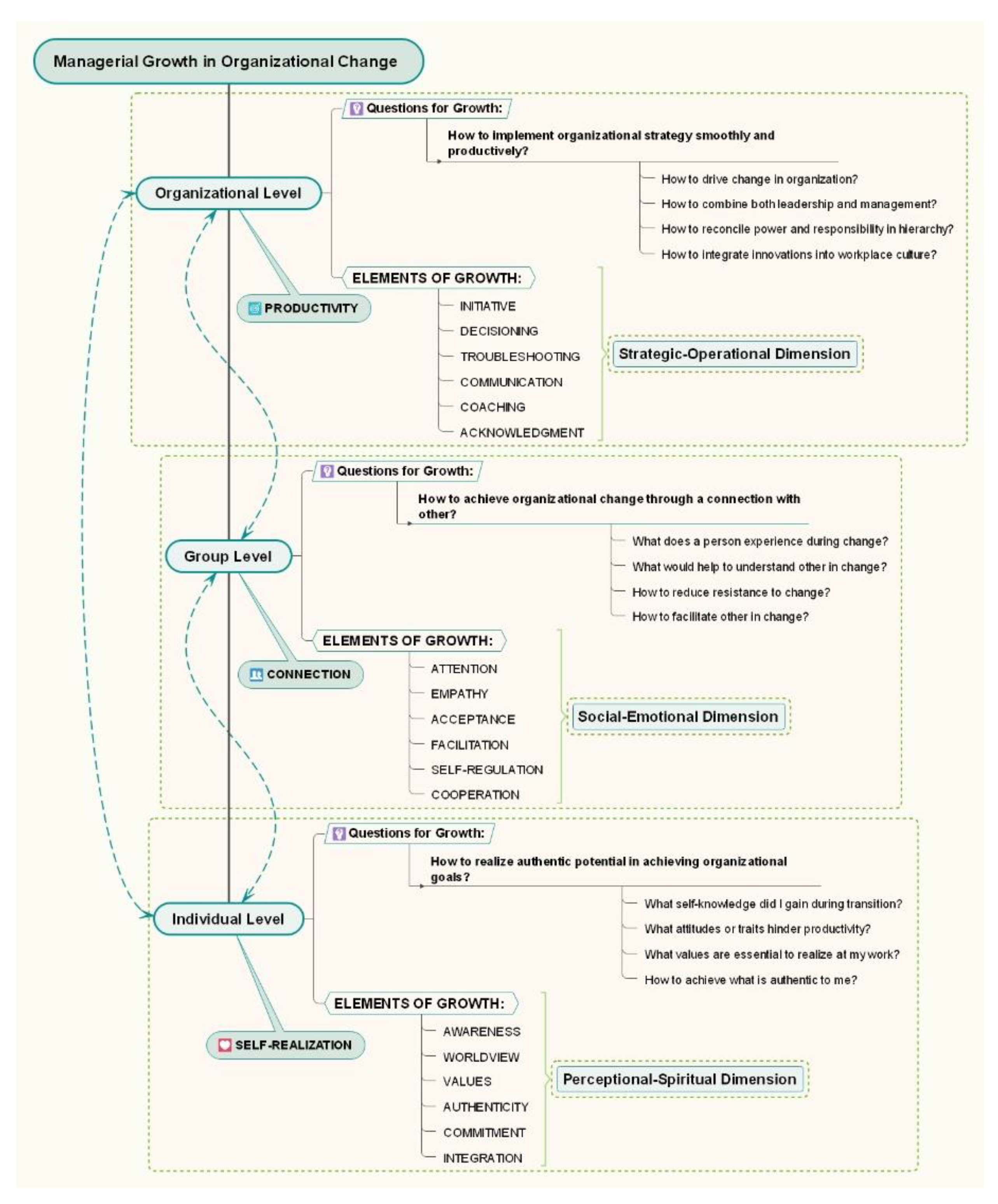

Based on six theoretical frameworks (Hiatt, Kotter, Kübler-Ross, Goleman, Mezirow, and Marcia), a three-dimensional perspective on managerial growth is formed through the creation of an emotionally supportive work environment with organizational change actors. This enables the achievement of strategic results at the individual, group, and organizational levels (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Elements of managerial growth in the context of organizational change.

Based on these findings, an integrated approach to managerial growth is presented that focuses on three aims of personal change—productivity, connection, and self-realization—in the context of long-term organizational transformations.

Managerial growth in the strategic-operational dimension includes the pursuit of productivity which is ensured through the elucidation of a clear change vision, the alignment of change actors’ interests, and gradual employee engagement in the process. Successful implementation of strategic goals and efficiency requires a combination of leadership and management skills as well as the readiness to integrate innovative solutions into established work procedures and organizational culture. Studies

[20] have diagnosed an important relationship between strategic leadership and both employee engagement and organizational transformation, whilst innovation does not escape challenges and “problem solving becomes the context for most learning”

[22] (p. 6). Other authors

[23][24] discuss the notion that not all managers have leadership skills, and agree with the view that professional development is related to the ability to initiate change in a group, troubleshoot, and flexibly maneuver in decision-making both within and outside the organization. Research shows that challenges arise when change is driven by external forces and when managers, especially those at the middle level, are not key decision makers

[16]. Promoting an alternative approach to organizational learning can occur externally and can force a response, such as “changes to political actors and regimes resulting from elections”

[25] (p. 151). Authors

[24][26] agree with results that suggest that the development of political awareness, reconciliation of different interests, and adaptability are crucial characteristics of a manager when navigating power relationships in the process of change. There is a need for future empirical research to address the following problem: What methods of self-development do managers use to combine existing powers and responsibilities at distinct levels of organizational hierarchy and collaborate with external forces?

Transparent and timely management communication becomes a crucial factor in the conscious formation of employee motivation in the context of organizational change. Managers are responsible for developing mutual dialogue with subordinates by logically explaining the need for change, representing opportunities and threats, and collecting feedback to understand background conversations

[16][20][23]. The growth of managers in the strategic-operational dimension also takes place by improving the competence of coaching, which includes focusing on staff training and individual counseling and providing timely feedback and proper evaluation of work efforts during organizational transformations. Bjerlöv and Docherty

[22] demonstrated that productive collective reflection is part of the learning process: it helps to develop mutual thinking about what a task is, how it is understood, and how it can be carried out in its existing context. It can be stated that a significant workload in the process of innovation implementation falls on middle managers, as they become direct change catalysts in organizing a fluent educational process, helping subordinates to adapt to a shift. De Klerk

[17] also observed that managerial growth starts by taking responsibility for listening to subordinates’ attitudes to change and becoming conductors of emotions to reduce the intensity of resistance. This research data correlates with studies

[12][13] that suggest that opaque communication creates an emotionally unfavorable and inefficient atmosphere in the workplace.

This research shows that a crucial path to managerial growth is to approach radical organizational changes as a painful loss from the perspective of employees. Studies

[4][5][6][7][8][10][11][12][13] emphasize that employees perceive uncomfortable inner experiences and emotions associated with personal financial, professional, social, and psychological losses. The healing of traumatic emotions is essential to avoid feeling stuck in organizational transitions

[17] so a manager’s careful analysis of relationship dynamics and conscious recognition of the emotional spectrum while facilitating change is a part of their professional growth.

These findings address studies on pandemic consequences

[2][7][27]. Managerial growth in the social-emotional dimension provides guidelines on how to navigate the working from home scenario; realizing that social distancing is the loss of direct collegial relationships encourages managers to adapt to new models of practice through facilitative acceptance of group dynamics and empathic attention, creating a sense of belonging in distanced communication with subordinates.

Therefore, managerial growth in terms of the social-emotional dimension overlaps a sustainable connection. Employee involvement is an integral part of cooperative success because they implement initiatives of their own leadership and decide on the outcome of the activity

[20]. Conscious managerial efforts are designed to neutralize resistance and motivate subordinates. Castillo et al.

[8] showed that various stages of organizational change typically deteriorate relationships with supervisors and co-workers. Consequently, the growth of managers includes not only the consistent coaching of employees during transformations but also the development of emotional relationships with subordinates and strengthening social cooperation. Studies

[25][28] affirm that the ability to conduct reflective and facilitative dialogue with subordinates can lead to mutual learning, deep understanding and insight, collaborative consciousness, and action. Resilient relationships ensure the support and commitment of subordinates

[12]. The importance of a social connection is also discussed in studies

[6][14] that stress empathy towards subordinates’ experiences, sensitive attention to their needs, and facilitation as essential elements of change that weaken resistance to transitions.

To achieve effective cooperation at the group level, the need for an active individual to work with oneself through the recognition of psychodynamic processes and conscious self-regulation becomes apparent. Some authors

[17][24] also claim that managers must develop the ability to perceive emerging emotions and recognize their impact on oneself and their environment, remaining still and centered. Contrarily, Bjerlöv and Docherty

[22] emphasize that stress arises from the frustration of efforts to make sense of what different parties in a work situation—colleagues, superiors, customers, and suppliers—mean, intend, value, and prioritize in their interactions with each other so individual reflection cannot reduce the ambiguity, it requires interaction.

This research is based on the attitude that each person is primarily an employee and only then a manager. A manager’s self-development discourse needs to be analyzed from the human perspective to maintain a balance between organizational change and personal growth in the perceptual-spiritual dimension. Studies

[11][12][17] also emphasize that larger-scale structural changes inextricably affect all workers and can become traumatic experiences as they touch on aspects of physical and psychological security, relationship expression, and other emotional issues. Change takes a unique meaning for each person because “individuals are already aware of their current state: health, comfort level, financial position, relationships, satisfaction with work, family status and many other factors that comprise their personal situations”

[16] (p. 46).

The goal of managerial growth at the individual level is self-realization which is anchored in a commitment that ensures the integration of internal and external expectations and a more focused motivation to work. This research argues that an intense physical, mental, and emotional workload can be a stimulus for authentic self-knowledge and personal growth through the emergence of unexpected value insights, leading to awareness raising, worldview transformations, and identity grounding. Bjerlöv and Docherty

[22] note that “understanding work, job design, organization, and its activities depends upon the possibility of comparing one’s own perceptions and experiences with those of others, <…> because there is a lack of clarity or consistency regarding such factors as values, goals, intentions, resources, limits, and domains, authority, and discretion”. The data obtained suggest organizational change is equivalent to critical experiences, which other authors refer to as “dissociating dilemmas”

[22] or “disequilibrating circumstances”

[4]. Research supports the idea that the highest potential for managerial growth corresponds to the examination of critical experiences leading to conscious choices; reflective insights force a shift in human perception, value systems, and behavioral patterns, affecting the authentic decisions of both learning and management. This corresponds to other authors’

[22][29][30][31] propositions that the deepest discoveries about oneself, one’s environment, and one’s life are formed by significant changes, including in the professional field. Such transformations reveal the authentic identity and promote human self-realization in personal and social lives, helping to adapt to the socio-cultural context

[32][33].

Changes are constant and inevitable in the modern business environment and some authors

[25] (p. 147) even state that change is “undoubtedly afoot in terms of new management doctrines”. This requires deeper scientific investigations, discerning the phenomenon of managerial growth in general and in organizational transitions. Management practitioners also have opposing viewpoints regarding priorities that managers must follow, e.g., Maxwell

[24] acknowledges development by serving people first, while Horowitz

[34] states that this is completely different in peace and war because management is related to organizational survival. Therefore, another aspect for future research might overlap the context of managerial growth with modes of organizational development and optimization.

Summarizing the results of this research, managerial growth in organizational change is revealed to moderate multidimensionality on the organizational, group, and personal levels. This means that a manager can encompass change targets from everyone’s perspective and experience—including themselves. The challenge is to face uncertainty and stress with the ability to recognize and manage polarity, paradox, and dilemma

[35][36]. These results complement studies

[10][11][12][13] which suggest that managing change in an organization, regardless of the human context and the role of participants in the process, becomes a challenge in integrating innovation into a work culture in the long term because of constant strife and conflict and also because of the loss of motivation and the risk of rotation

[37]. Relating to this, other research supports an integrated approach to managerial growth by expanding scientific knowledge to change management, organizational psychology, and lifelong learning.

The researchers tend to explain and represent the directions of managerial growth, but do not expand the content of detailed “know how” techniques to achieve results. The cause of this might be the complexity of the topic and too broad a range of employed literature having been selected for theory synthesis. Another limitation is that chosen theoretical approaches are not new and may not reflect the latest research and realities.

Research implications overlap practical guidelines for middle managers in (1) understanding the underpinnings of possible organizational change dynamics and resonance in them; and (2) taking advantage of good practices related to self-development directions to help oneself and one’s subordinates. The research also provides insights for HR professionals via: (1) topics for staff training such as self-care, emotional intelligence, and change management in general; (2) knowledge on the necessary self-developmental skills of middle managers when recruiting them for planned future organizational change; and (3) insights into how to form an emotionally favorable organizational culture and traditions that foster a cooperative work environment. These findings may also contribute to overall organizational development, stressing some ideas for the heads of organizations to provide more financial resources to support middle managers during organizational change and to ensure transparent communication on change strategy to prevent the confusion and stress of managers. These research implications might also be adapted in the context of higher education for study program developers and lecturers to supplement management, psychology, and other disciplinary study programs that respond to the topics and problems of organizational change, addressing the knowledge and skills necessary for change managers or middle managers.