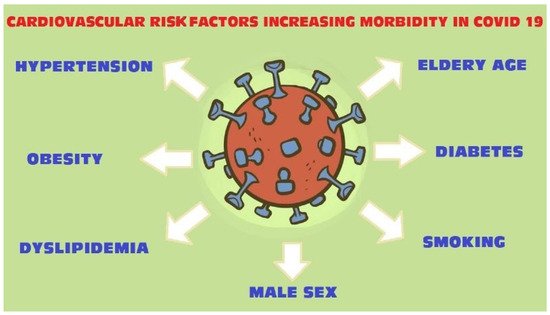

The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic is spreading around the world and becoming a major public health crisis. All coronaviruses are known to affect the cardiovascular system. There is a strong correlation between cardiovascular risk factors and severe clinical complications including death in COVID-19 patients (Figure 1).

Diversified lifestyle, access to health care and prophylaxis, and an aging society contribute to the increasing number of patients suffering from civilization diseases such as obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and diabetes. The presence of those comorbidities may deteriorate the course of COVID-19 infection.

2. Obesity

2.1. Methods

RWe

searchers searched PubMed and Google Scholar databases, using the terms, “COVID-19 obesity”, “COVID-19 mortality obesity patients” as well as keywords such as “cardiovascular risk factors”, “obesity risk infections”. Further studies were sought by manually searching reference lists of the relevant articles. Relevant articles were selected based on their title, abstract or full text. Articles were excluded if they were clearly related to another subject matter or were not published in English. Out of 163 publications,

researcherswe selected 20 for this subtitle.

2.2. Findings

Obesity, defined as BMI over 30 kg/m

2 is associated with various disorders such as cardiovascular diseases, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes mellitus, obstructive sleep apnea and some cancers

[6][7][6,7]. It affects the immune response

[8], endothelium imbalance

[9], release of cytokines

[10] and promotes chronic systemic inflammation

[11]. All these features contribute to a worse course of infectious disease, prolonged hospitalization and worse outcomes in obese patients

[12][13][14][12,13,14]. Therefore COVID-19 patients with obesity require particular attention.

In a study of 10,544 COVID-19 population, patients with a BMI of 30–40 kg/m

2 had an increased risk for hospitalization and clinical deterioration compared to patients with a BMI below 30 kg/m

2 [15]. In another study considering the COVID-19 infection, obesity together with age ≥ 52 years was strongly associated with illness severity

[16]. Obesity was also shown as a high-risk factor for middle aged adult in a 3615 patients study. The authors suggested that obese patients aged between 52 and 60 years were more exposed to increased morbidity rates compared to patients > 60 years old

[1]. What is more interesting, is there are studies that have reported the relation between poor prognosis of obese COVID-19 patients and gender. In a study by Cai Q et al.

[17], the increased disease severity was correlated with the male sex. Similarly, Chiumello D.

[18] found strong association between acute respiratory distress and male sex in overweight/obese patients. In contrast, a study of 32,583 patients indicated higher odds ratios in females than males. The authors suggested that females with obesity, diabetes and hypertension are more susceptible to COVID-19 and have a higher odds ratio for a severe COVID-19 course

[19].

Obese patients more often demonstrated a cough and fever as initial symptoms, compared to normal weight patients

[17]. Interestingly, in a small clinical study it was found that the increased area of visceral adipose tissue (measured at the level of the first lumbar vertebra on chest computed tomography) and upper abdominal circumference were associated with a higher probability of intensive care unit treatment or mechanical ventilation (adjusted for age and sex)

[20]. There is also a strong association between a high BMI and mortality among the COVID-19 population. In a cohort of 20,133 cases, Docherty et al.

[21] proved that obesity was significantly associated with a higher in-hospital mortality as well as older age, male sex and comorbidities such as chronic cardiac disease, chronic pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease and liver disease. Further data from a Mexican study with 4103 COVID-19 cases showed a significant increase in hospitalization and mortality rate in patients with obesity

[22]. Likewise, numerous clinical studies confirm the influence of obesity on outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection

[23][24][23,24].

3. Lipid Profile

3.1. Methods

ResearchWe

rs choose 19 from 59 publications, found in PubMed, using keywords: “lipid profile and COVID-19 infections”, “hyperlipidemia/dyslipidemia and COVID-19”, “statins COVID”. The works

researcherswe used are mainly relevant reviews, original publications and the literature they contain. Non-English articles were excluded.

3.2. Findings

The lipid profile plays a key role in viral infection. The cholesterol membrane was found as an important component for pathogenic viruses entering host cells

[25]. Hao Wang et al.

[26] indicated that a high level of cholesterol in the cellular membranes of tissue enhanced the entry of the virus. The authors suggested that high cellular cholesterol indicates SARS-CoV-2 infectivity. The average cellular cholesterol level in the lung increases with age, thereby the number of viral entry points rises. When cholesterol is low, as in children, there are only a few entry points. In chronically ill patients, where the cellular cholesterol level is high (mostly due to age and chronic inflammation), all the angiotensin I converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors are positioned for viral infectivity. However, blood sample analysis did not correlate with cholesterol levels in the tissue cell membranes. This is because the chronic inflammatory process prompts the inhibition of cholesterol efflux proteins in the peripheral tissue. In a study with infectious bronchitis coronavirus, it was demonstrated that reduction of cholesterol prevented the binding of coronavirus with the host cells

[27]. In another study with porcine deltacoronavirus, the authors observed the pharmacological reduction of cellular or viral cholesterol might block virus attachment and internalization

[28]. On the other hand, a clinical study in China showed lower serum lipid levels (total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol) in patients with COVID-19 infection compared to healthy controls. It was noticed that cholesterol level continued to drop during the first few days of infection and then gradually rose. The authors suggested the lipid changes might be related to viral–host cell fusion and entry, and thus may indirectly indicate the effectiveness of the COVID-19 treatment regimens

[29].

There is evidence suggesting statins influence the course of COVID-19 infection, which could be useful in treatment. Statins are cholesterol-lowering drugs that possess beneficial effects such as anti-thrombotic, immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory functions

[30]. As a result of controlling cytokine overexpression and modulating immune responses, statins may prevent ARDS and may reduce the incidence of cardiovascular complications in COVID-19 patients

[31][32][31,32]. Statin treatment may block viral infectivity through inhibition of glycoprotein processing

[33]. The SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro), a key coronavirus enzyme, has been examined as a potential protein target to prevent infection expansion

[34]. Željko Reiner et al.

[2] indicated that statins could be SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors and may block entry of the virus into host cells.

There is also data indicating statins’ ability to upregulate ACE2 signaling pathways, which could mitigate the invasion of SARS-CoV-2 through the ACE2 receptor

[35]. A high level of ACE2 in pulmonary endothelium was associated with reduced severity of ARDS

[36]. Moreover, statins might counteract SARS-CoV-2-induced endothelitis in lungs by promoting endothelial repair and accelerate recovery from ARDS in COVID-19 patients

[37][38][37,38]. Statins, through their anti-inflammatory effects, protect from the occurrence of plaque rupture and, therefore, reduce the risk of myocarditis and cardiac injury in COVID-19 patients

[39][40][39,40].

Retrospective data showed a positive impact of statin use on mortality and in-hospital outcomes in the COVID-19 population. In a retrospective study of 2147 patients with COVID-19, the multivariate Cox model showed, after adjusting for age, gender, comorbidities, in-hospital medications and blood lipids, lower risk of mortality, acute respiratory distress syndrome or intensive care unit treatment in the statin group vs. the non-statin group

[41]. Another study of 13,981 patients with COVID-19, among which 1219 received statins 28-day all-cause mortality was significantly lower than in the non-statin group

[42]. On the other hand, in a meta-analysis of retrospective observational studies investigating the impact of previous statin use in COVID-19 patients, no significant reductions in either in-hospital mortality or COVID-19 severity were reported among statin users. However, such reductions were found after adjusting for confounding risk factors

[43].