Bacterial resistance is an emergency public health problem worldwide, compounded by the ability of bacteria to form biofilms, mainly in seriously ill hospitalized patients. The World Health Organization has published a list of priority bacteria that should be studied and, in turn, has encouraged the development of new drugs. Herein, we explain the importance of studying new molecules such as antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) with potential against multi-drug resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) bacteria and focus on the inhibition of biofilm formation. This review describes the main causes of antimicrobial resistance and biofilm formation, as well as the main and potential AMP applications against these bacteria. Our results suggest that the new biomacromolecules to be discovered and studied should focus on this group of dangerous and highly infectious bacteria. Alternative molecules such as AMPs could contribute to eradicating biofilm proliferation by MDR/XDR bacteria; this is a challenging undertaking with promising prospects.

- Antimicrobial Peptides

- Multi-Drug Resistant Bacteria

- Biofilms

1. Introduction

2. Antimicrobial Peptides and Applications

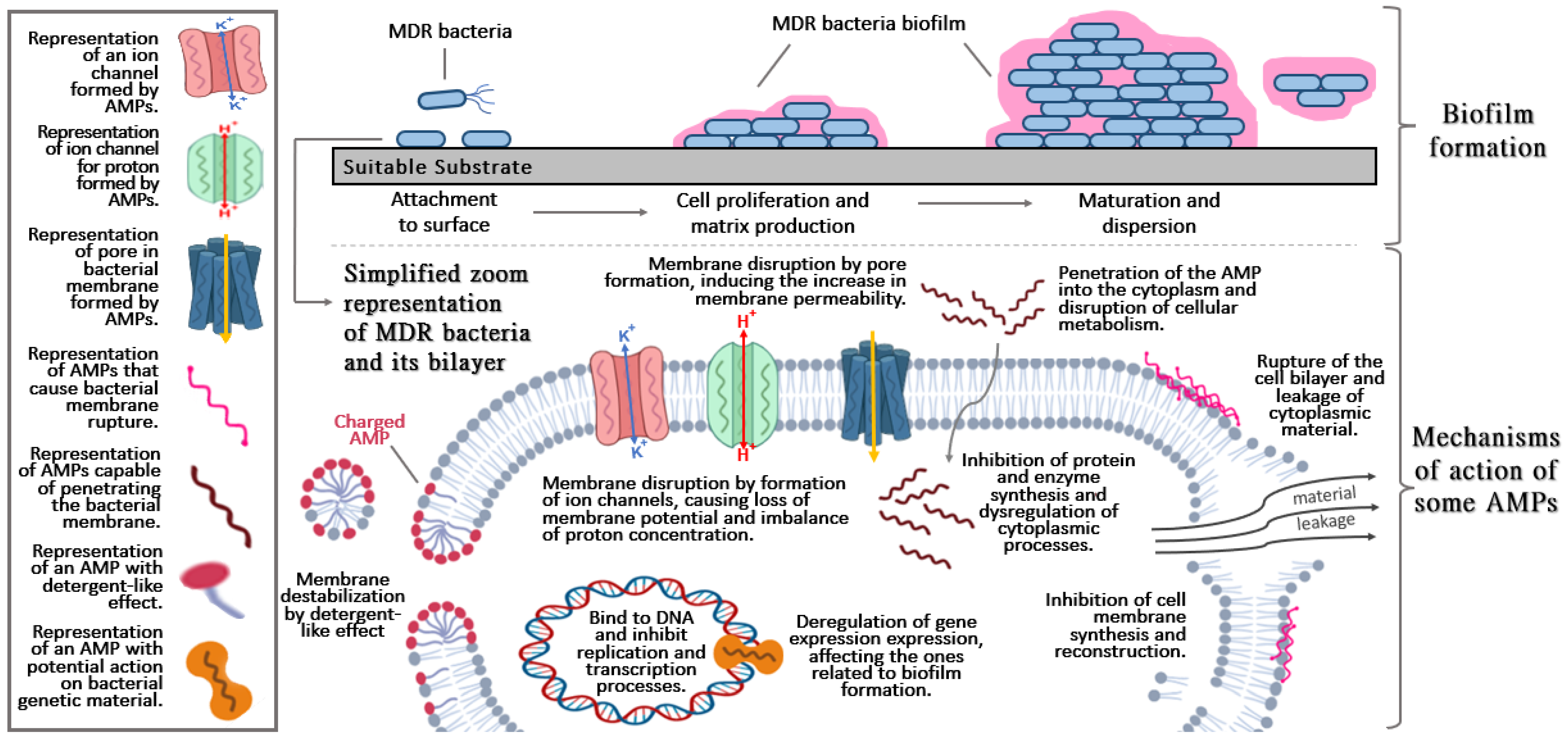

AMPs are biomolecules formed by amino acids that vary in length, usually composed of 12–50 amino acids [60][7]. They are known to have great antifungal, antiviral, and antibacterial properties and are capable of reducing the bacterial load and avoiding resistance due to their ability to associate rapidly with the membrane [7][8]. AMPs are also small protein fractions with biological activity and are part of the body’s first line of defense for pathogen inactivation [61][9]. The first AMPs discovered and studied were based on structures related to defensins since these molecules were produced innately when some pathogenic agent came into contact with organisms [4]. AMPs are capable of modulating the immune system and generating a better response to defend the host since previous studies would indicate this potential as a single molecule [62[10][11][12],63,64], or in combination with another drugs, causing an even more beneficial and less toxic synergistic effect [65,66][13][14]. AMPs have an amphipathic nature because they are composed of hydrophilic and hydrophobic regions, although they are mostly hydrophobic. This allows them to interact with biological membranes due to van der Waals interactions with the membrane lipid tails, which are natural in cell membranes [67][15]. Most AMPs have a cationic behavior that promotes the interaction with membrane headgroup components [68,69][16][17]. They can adopt different secondary structures that influence their mechanism according to their physicochemical characteristics (Figure 1); the mechanism of action is also influenced by the net charge, amphipathicity, and number of amino acids [70][18]. AMPs act against bacteria due to membrane disruption and/or pore formations. Other actions consist of the inhibition of proteins, enzymes, and cell wall synthesis when they are present in the cytoplasm [67][15]. Due to this ability, shown in many studies, AMPs are considered effective against MDR bacteria and fungi cells [71][19]. Figure 1. Basic and general aspects of biofilm formation (upper section) and brief description of the mechanisms action of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) (lower section).

The neutralization or disassembly of lipopolysaccharides in these strategies uses AMPs, which can penetrate through the lipid bilayer, since they have a hydrophobic side and a hydrophilic side, allowing their solubilization in an aquatic environment [63][11]. AMPs are able to infiltrate the biofilm and cause bacterial death [72][20] due to their ability to electrostatically bind to lipopolysaccharides (LPS), involving interaction between two cationic amino acids (lysine and arginine) and their respective heads of groups, forming a complex. This complex destabilizes lipid groups due to the formation of multiple pores, impairing the integrity of the bacterial cell membrane [73][21]. This is due to the fact that the complex is stabilized through hydrophobic interactions between the hydrophobic amino acids of the peptide and the fatty acyl chains of LPS [63][11].

AMPs are considered an excellent alternative against resistant bacteria, in comparison with conventional antibiotics. This is due to their non-specific mechanism (ability to reach a variety of sites), which reduces the chances of resistance development. In addition, some AMPs have great anti-multi-resistant biofilm activity, interfering with the initiation of biofilm formation (preventing bacteria from adhering to surfaces) or destroying mature biofilms (killing the bacteria present or causing them to detach) [74][22].

According to Wang et al. [99][23], AMPs may have the ability to inhibit the expansion of biofilms, and not always eliminating all microorganisms such as Nal-P-113 against Porphyromonas gingivalis W83 biofilms formation; therefore, the authorscholars suggest its application with other drugs currently used for the oral treatment of this potentially virulent bacterium. Likewise, some studies report that their synergistic or combined effect could improve with the inclusion or structural modification of AMP; for example, chimeric peptide-Titanium conjugate (TiBP1-spacer-AMP y TiBP2-spacer-AMP) against Streptococcus mutans, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Escherichia coli [100][24], A3-APO (proline-rich AMP) combined with imipenem against ESKAPE pathogens, biofilm-forming bacteria and in vivo murine model [101,102][25][26]. In addition, it was reported that modifications in the C terminal with fatty acids could further improve the specificity and activity of AMPs against superbugs and their respective biofilms [103,104][27][28]. Another study revealed that the addition of a hydrazide and using perfluoroaromatic (tetrafluorobenzene and octofluorobiphenyl) linkers enhance the antibacterial and antibiofilm activity demonstrated against MDR and XDR A. baumannii [105][29]. Table 31 shows promising applications of AMPs against biofilm formation.

Figure 1. Basic and general aspects of biofilm formation (upper section) and brief description of the mechanisms action of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) (lower section).

The neutralization or disassembly of lipopolysaccharides in these strategies uses AMPs, which can penetrate through the lipid bilayer, since they have a hydrophobic side and a hydrophilic side, allowing their solubilization in an aquatic environment [63][11]. AMPs are able to infiltrate the biofilm and cause bacterial death [72][20] due to their ability to electrostatically bind to lipopolysaccharides (LPS), involving interaction between two cationic amino acids (lysine and arginine) and their respective heads of groups, forming a complex. This complex destabilizes lipid groups due to the formation of multiple pores, impairing the integrity of the bacterial cell membrane [73][21]. This is due to the fact that the complex is stabilized through hydrophobic interactions between the hydrophobic amino acids of the peptide and the fatty acyl chains of LPS [63][11].

AMPs are considered an excellent alternative against resistant bacteria, in comparison with conventional antibiotics. This is due to their non-specific mechanism (ability to reach a variety of sites), which reduces the chances of resistance development. In addition, some AMPs have great anti-multi-resistant biofilm activity, interfering with the initiation of biofilm formation (preventing bacteria from adhering to surfaces) or destroying mature biofilms (killing the bacteria present or causing them to detach) [74][22].

According to Wang et al. [99][23], AMPs may have the ability to inhibit the expansion of biofilms, and not always eliminating all microorganisms such as Nal-P-113 against Porphyromonas gingivalis W83 biofilms formation; therefore, the authorscholars suggest its application with other drugs currently used for the oral treatment of this potentially virulent bacterium. Likewise, some studies report that their synergistic or combined effect could improve with the inclusion or structural modification of AMP; for example, chimeric peptide-Titanium conjugate (TiBP1-spacer-AMP y TiBP2-spacer-AMP) against Streptococcus mutans, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Escherichia coli [100][24], A3-APO (proline-rich AMP) combined with imipenem against ESKAPE pathogens, biofilm-forming bacteria and in vivo murine model [101,102][25][26]. In addition, it was reported that modifications in the C terminal with fatty acids could further improve the specificity and activity of AMPs against superbugs and their respective biofilms [103,104][27][28]. Another study revealed that the addition of a hydrazide and using perfluoroaromatic (tetrafluorobenzene and octofluorobiphenyl) linkers enhance the antibacterial and antibiofilm activity demonstrated against MDR and XDR A. baumannii [105][29]. Table 31 shows promising applications of AMPs against biofilm formation.

| Peptide | Sequence and Properties | Antimicrobial Activity | Highlights | Reference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myxinidin2 Myxinidin3 | KIKWILKYWKWS RIRWILRYWRWS | P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, | and | L. monocytogenes | Effects against a wide range of bacteria, with its mechanism of action based on its ability to insert into bacterial membranes to produce an ion channel or pore that disrupts membrane function. | [106] | [30] | ||

| Colistin (colistin–imipenem and colistin–ciprofloxacin) | ALYKKLLKKLLKSAKKLG | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli | and | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Bactericidal mechanism by a detergent-like effect. Recommended as a last choice in the treatment of infections caused by MDR Gram-negative bacteria because it rarely causes bacterial resistance. | [107] | [31] | ||

| S4(1–16)M4Ka | ALWKTLLKKVLKAAAK-NH2 | P. fluorescens | Greater antimicrobial effect and less toxicity than its parent peptide (dermaseptin S4) | [108] | [32] | ||||

| Pexiganan | GIGKFLKKAKKFGKAFVKILKK-NH2 | S. aureus, S. epidermidis, S. pyogenes, S. pneumoniae, E. coli | and | P. aeruginosa | Weak anti-biofilm agent against structures formed on CL. | [109] | [33] | ||

| Citropin 1.1 | GLFDVIKKVASVIGGL-NH2 | Potent anti-biofilm agent against | S. aureus | strains. | |||||

| Temporin A: | FLPLIGRVLSGIL-NH2 | Strong activity against vancomycin-resistant strains. | |||||||

| Palm-KK-NH2 | Palm-KK-NH2 (Palm–hexadecanoic acid residue) | Effective against most strains in the form of a biofilm. Activity potentiated when combined with standard antibiotics. | |||||||

| Palm-RR-NH2 | Palm-RR-NH2 (Palm–hexadecanoic acid residue) | Efficiency potentiated when combined with standard antibiotics. | |||||||

| HB AMP | KKVVFWVKFK + HAp-binding heptapeptide (HBP7) | S. mutans, L. acidophilus | and | A. viscosus | Adsorption capacity on the dental surface. | [110] | [34] | ||

| KSLW | KKVVFWVKFK | Promising peptide for oral use as it is resistant to the gastrointestinal tract and stable in human saliva. | |||||||

| TiBP1-GGG-AMP | RPRENRGRERGKGGGLKLLKKLLKLLKKL | S. mutans, S. epidermidis, | and | E. coli. | Bifunctional peptide capable of binding to titanium materials, enabling its use in biomaterials. Antibacterial functionality. | [100] | [24] | ||

| BA250-C10 | RWRWRWK(C | 10 | ) | P. aeruginosa | Great activity when used in synergism with two conventional anti-pseudomonas antibiotics to inhibit the planktonic growth of four strains of | P. aeruginosa. | [111] | [35] | |

| D-HB43 | FAKLLAKLAKKLL | Methicillin-resistant S. aureus strains | High cytotoxic and hemolytic effect. | [112] | [36] | ||||

| D-Ranalexin | FLGGLIKIVPAMICAVTKKC | Methicillin-resistant S. aureus strains | Effective in dose-dependent biofilm killing, but high cytotoxic and hemolytic effect. | ||||||

| FK13-a1 | WKRIVRRIKRWLR-NH2 | Methicillin-resistant S. aureus, | MDR | P. aeruginosa | and | vancomycin-resistant E. faecium | Mechanism of action based on the induction of cytoplasmic membrane potential loss, permeabilization, and rupture. | [113] | [37] |

| FK13-a7 | WKRWVRRWKRWLR-NH2 | Methicillin-resistant S. aureus, | MDR | P. aeruginosa | and | vancomycin-resistant E. faecium | Mechanism of action based on the induction of cytoplasmic membrane potential loss, permeabilization, and rupture. | ||

| KR-12-a5 | KRIVKLILKWLR-NH2 | E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. typhimurium, S. aureus, B. subtilis, S. epidermidis | This peptide and its analogs kill microbial cells by inducing loss of cytoplasmic membrane potential, permeabilization, and disruption. | [114] | [38] | ||||

| AMP2 | KRRWRIWLV | E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, E. faecalis, S. epidermidis | 76% reduction of the biofilm area. | [115] | [39] | ||||

| GH12 | GLLWHLLHHLLH-NH2 | S. mutans | Antimicrobial activity against cariogenic bacteria and its biofilms in vitro. | [116] | [40] | ||||

| TP4 | FIHHIIGGLFSAGKAIHRLIRRRRR | P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, S. aureus | Peptide driven into helix shape by an LPS-like surfactant before binding to the target. | [117] | [41] | ||||

| LyeTxI | IWLTALKFLGKNLGKHLALKQQLAKL | F. nucleatum, P. gingivalis, A. actinomycetemcomitans | Active against periodontopathic bacteria. Rapid bactericidal effect, prevention of biofilm development. Can be used in the dental field. | [118] | [42] | ||||

| Esc(1–21) | GIFSKLAGKKIKNLLISGLKG-NH2 | P. aeruginosa | Mechanism of action causes membrane thinning. | [119] | [43] | ||||

| L12 | LKKLLKKLLKKL-NH2 | P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, S. aureus, E. coli | Mechanism of action based on pore formation, inducing rapid permeabilization of bacterial membranes, inhibition of biofilm formation, disruption of drug-resistant biofilms, and suppression of LPS-induced pro-inflammatory mediators, even at low peptide concentrations. | [120] | [44] | ||||

| W12 | WKKWWKKWWKKW-NH2 | Suppression of LPS-induced pro-inflammatory mediators, even at low peptide concentrations. | |||||||

| WLBU2 | RRWVRRVRRVWRRVVRVVRRWVRR | E. faecium, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa | and | Enterobacter | species | Mechanism of action based on preventing bacterial adhesion and interfering with gene expression. | [121,122] | [45][46] | |

| LL37 | LLGDFFRKSKEKIGKEFKRIVQRIKDFLRNLVPRTES | E. faecium, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa | and | Enterobacter | species | One of the most important human AMPs that play roles in the defense against local and systemic infections. Bactericidal mechanism against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria based on phospholipid-dependent bacterial membrane disruption. | [121,123] | [45][47] | |

| SAAP-148 | LKRVWKRVFKLLKRYWRQLKKPVR | E. faecium, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa | and | Enterobacter | species | Promising peptide fights difficult-to-treat infections due to its broad antimicrobial activity against MDR, biofilm, and persistent bacteria. | [124] | [48] | |

| WAM-1 | KRGFGKKLRKRLKKFRNSIKKRLKNFNVVIPIPLPG | A. baumannii | This peptide originates from LL37 AMPs and is more effective in inhibiting biofilm dispersion than its parent peptide. | [125] | [49] | ||||

| H4 | KFKKLFKKLSPVIGKEFKRIVERIKRFLR | S. aureus, S. epidermidis, S. pneumoniae, E. coli, E. faecium, K. pneumoniae, | and | P. aeruginosa | Insignificant rates of toxicity to eukaryotic cells. | [126] | [50] | ||

| RWRWRWA-(Bpa) | RWRWRWA-(4-benzophenylalanine) | P. aeruginosa | It targets the bacterial lipid membrane, but there is no specific receptor. It only affects a range of cellular processes. | [127] | [51] | ||||

| Pse-T2 | LNALKKVFQKIHEAIKLI-NH2 | P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, E. coli | Mechanism of action based on the ability to disrupt the outer and inner membrane of Gram-negative bacteria and to bind DNA. | [128] | [52] | ||||

| Magainin 2 | GIGKFLHSAKKFGKAFVGEIMNS-NH2 | A. baumannii strains | Strong antibacterial activity against | A. baumannii, | including MDR strains. Non-toxic to mammalian cells. | [129] | [53] | ||

| Magainin I | GIGKFLHSAGKFGKAFVGEIMKS | E. coli strains | Demands more energy metabolism, translational processes, and bacterial defense in | E. coli | strains when present. | [130] | [54] | ||

| TC19 | LRCMCIKWWSGKHPK | B. subtilis strains | Promising peptide against Gram-positive bacteria, as its activity on the membrane interferes with several essential cellular processes, leading to bacterial death. | [131] | [55] | ||||

| TC84 | LRAMCIKWWSGKHPK | Promising peptide against Gram-positive bacteria, as its activity on the membrane interferes with several essential cellular processes, leading to bacterial death. | |||||||

| BP2 | GKWKLFKKAFKKFLKILAC | B. subtilis strains | Promising peptide against Gram-positive bacteria, as its activity by perturbation of the membrane interferes with several essential cellular processes, leading to bacterial death. | [132] | [56] | ||||

| Nisin A | MSTKDFNLDLVSVSKKDSGASPRITSISLCTPGCKTGALMGCNMKTATCHCSIHVSK | B. subtilis spores | Application as an adjuvant to antibiotic peptides in providing a bactericidal coating for the spores. | [131,133] | [55][57] |

References

- WHO. Critically Important Antimicrobials for Human Medicine: Ranking of Antimicrobial Agents for Risk Management of Antimicrobial Resistance due to Non-Human Use, 5th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Sultan, I.; Rahman, S.; Jan, A.T.; Siddiqui, M.T.; Mondal, A.H.; Haq, Q.M.R. Antibiotics, resistome and resistance mechanisms: A bacterial perspective. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2066.

- Gedefie, A.; Demsis, W.; Ashagrie, M.; Kassa, Y.; Tesfaye, M.; Tilahun, M.; Bisetegn, H.; Sahle, Z. Acinetobacter baumannii Biofilm Formation and Its Role in Disease Pathogenesis: A Review. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 3711.

- Magana, M.; Pushpanathan, M.; Santos, A.L.; Leanse, L.; Fernandez, M.; Ioannidis, A.; Giulianotti, M.A.; Apidianakis, Y.; Bradfute, S.; Ferguson, A.L.; et al. The value of antimicrobial peptides in the age of resistance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, e216–e230.

- Vestby, L.K.; Grønseth, T.; Simm, R.; Nesse, L.L. Bacterial Biofilm and its Role in the Pathogenesis of Disease. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 59.

- Jiménez Hernández, M.; Soriano, A.; Filella, X.; Calvo, M.; Coll, E.; Rebled, J.M.; Poch, E.; Graterol, F.; Compte, M.T.; Maduell, F.; et al. Impact of locking solutions on conditioning biofilm formation in tunnelled haemodialysis catheters and inflammatory response activation. J. Vasc. Access 2021, 22, 370–379.

- AlMatar, M.; Makky, E.A.; Yakıcı, G.; Var, I.; Kayar, B.; Köksal, F. Antimicrobial peptides as an alternative to anti-tuberculosis drugs. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 128, 288–305.

- Roque-Borda, C.A.; Silva, P.B.D.; Rodrigues, M.C.; Azevedo, R.B.; Filippo, L.; Di Duarte, J.L.; Chorilli, M.; Vicente, E.F.; Pavan, F.R. Challenge in the Discovery of New Drugs: Antimicrobial Peptides against WHO-List of Critical and High-Priority Bacteria. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 773.

- Silveira, R.F.; Roque Borda, C.A.; Vicente, E.F. Antimicrobial peptides as a feed additive alternative to animal production, food safety and public health implications: An overview. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 7, 896–904.

- Roque-Borda, C.A.; Souza Saraiva, M.d.M.; Monte, D.F.M.; Rodrigues Alves, L.B.; de Almeida, A.M.; Ferreira, T.S.; de Lima, T.S.; Benevides, V.P.; Cabrera, J.M.; Claire, S.; et al. HPMCAS-Coated Alginate Microparticles Loaded with Ctx(Ile21)-Ha as a Promising Antimicrobial Agent against Salmonella Enteritidis in a Chicken Infection Model. ACS Infect. Dis. 2022, 8, 472–481.

- Mahlapuu, M.; Håkansson, J.; Ringstad, L.; Björn, C. Antimicrobial Peptides: An Emerging Category of Therapeutic Agents. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2016, 6, 194.

- Roque-Borda, C.A.; Pereira, L.P.; Guastalli, E.A.L.; Soares, N.M.; Mac-Lean, P.A.B.; Salgado, D.D.; Meneguin, A.B.; Chorilli, M.; Vicente, E.F. Hpmcp-coated microcapsules containing the ctx(Ile21)-ha antimicrobial peptide reduce the mortality rate caused by resistant salmonella enteritidis in laying hens. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 616.

- Morroni, G.; Simonetti, O.; Brenciani, A.; Brescini, L.; Kamysz, W.; Kamysz, E.; Neubauer, D.; Caffarini, M.; Orciani, M.; Giovanetti, E.; et al. In vitro activity of Protegrin-1, alone and in combination with clinically useful antibiotics, against Acinetobacter baumannii strains isolated from surgical wounds. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2019, 208, 877–883.

- Martinez, M.; Gonçalves, S.; Felício, M.R.; Maturana, P.; Santos, N.C.; Semorile, L.; Hollmann, A.; Maffía, P.C. Synergistic and antibiofilm activity of the antimicrobial peptide P5 against carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Biomembr. 2019, 1861, 1329–1337.

- Pletzer, D.; Hancock, R.E.W. Antibiofilm peptides: Potential as broadspectrum agents. J. Bacteriol. 2016, 198, 2572–2578.

- Raheem, N.; Straus, S.K. Mechanisms of Action for Antimicrobial Peptides With Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Functions. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2866.

- Wu, Q.; Patočka, J.; Kuča, K. Insect Antimicrobial Peptides, a Mini Review. Toxins 2018, 10, 461.

- Seyfi, R.; Kahaki, F.A.; Ebrahimi, T.; Montazersaheb, S.; Eyvazi, S.; Babaeipour, V.; Tarhriz, V. Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs): Roles, Functions and Mechanism of Action. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2020, 26, 1451–1463.

- Galdiero, E.; Lombardi, L.; Falanga, A.; Libralato, G.; Guida, M.; Carotenuto, R. Biofilms: Novel Strategies Based on Antimicrobial Peptides. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 11, 322.

- Pulido, D.; Nogús, M.V.; Boix, E.; Torrent, M. Lipopolysaccharide Neutralization by Antimicrobial Peptides: A Gambit in the Innate Host Defense Strategy. J. Innate Immun. 2012, 4, 327.

- Vicente, E.F.; Basso, L.G.M.; Crusca Junior, E.; Roque-Borda, C.A.; Costa-Filho, A.J.; Cilli, E.M. Biophysical Studies of TOAC Analogs of the Ctx(Ile21)-Ha Antimicrobial Peptide Using Liposomes. Braz. J. Phys. 2022, 52, 71.

- Yasir, M.; Willcox, M.D.P.; Dutta, D. Action of Antimicrobial Peptides against Bacterial Biofilms. Materials 2018, 11, 2468.

- Wang, H.Y.; Lin, L.; Tan, L.S.; Yu, H.Y.; Cheng, J.W.; Pan, Y.P. Molecular pathways underlying inhibitory effect of antimicrobial peptide Nal-P-113 on bacteria biofilms formation of Porphyromonas gingivalis W83 by DNA microarray. BMC Microbiol. 2017, 17, 37.

- Yazici, H.; O’Neill, M.B.; Kacar, T.; Wilson, B.R.; Emre Oren, E.; Sarikaya, M.; Tamerler, C. Engineered Chimeric Peptides as Antimicrobial Surface Coating Agents toward Infection-Free Implants HHS Public Access. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 5070–5081.

- Pletzer, D.; Mansour, S.C.; Hancock, R.E.W. Synergy between conventional antibiotics and anti-biofilm peptides in a murine, sub-cutaneous abscess model caused by recalcitrant ESKAPE pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007084.

- Otvos, L.; Ostorhazi, E.; Szabo, D.; Zumbrun, S.D.; Miller, L.L.; Halasohoris, S.A.; Desai, P.D.; Veldt, S.M.I.; Kraus, C.N. Synergy between proline-rich antimicrobial peptides and small molecule antibiotics against selected Gram-Negative pathogens in vitro and in vivo. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 309.

- Li, W.; Separovic, F.; O’Brien-Simpson, N.M.; Wade, J.D. Chemically modified and conjugated antimicrobial peptides against superbugs. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 4932–4973.

- Dong, W.; Luo, X.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Guan, Y.; Shang, D. Binding Properties of DNA and Antimicrobial Peptide Chensinin-1b Containing Lipophilic Alkyl Tails. J. Fluoresc. 2020, 30, 131–142.

- Li, W.; Lin, F.; Hung, A.; Barlow, A.; Sani, M.-A.; Paolini, R.; Singleton, W.; Holden, J.; Hossain, M.A.; Separovic, F.; et al. Enhancing proline-rich antimicrobial peptide action by homodimerization: Influence of bifunctional linker. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 2226–2237.

- Han, H.M.; Gopal, R.; Park, Y. Design and membrane-disruption mechanism of charge-enriched AMPs exhibiting cell selectivity, high-salt resistance, and anti-biofilm properties. Amin. Acids 2015, 48, 505–522.

- Dosler, S.; Karaaslan, E.; Gerceker, A.A. Antibacterial and anti-biofilm activities of melittin and colistin, alone and in combination with antibiotics against Gram-negative bacteria. J. Chemother. 2016, 28, 95–103.

- Quilès, F.; Saadi, S.; Francius, G.; Bacharouche, J.; Humbert, F. In situ and real time investigation of the evolution of a Pseudomonas fluorescens nascent biofilm in the presence of an antimicrobial peptide. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Biomembr. 2016, 1858, 75–84.

- Maciejewska, M.; Bauer, M.; Neubauer, D.; Kamysz, W.; Dawgul, M. Influence of Amphibian Antimicrobial Peptides and Short Lipopeptides on Bacterial Biofilms Formed on Contact Lenses. Materials 2016, 9, 873.

- Huang, Z.; Shi, X.; Mao, J.; Gong, S. Design of a hydroxyapatite-binding antimicrobial peptide with improved retention and antibacterial efficacy for oral pathogen control. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38410.

- De Gier, M.G.; Bauke Albada, H.; Josten, M.; Willems, R.; Leavis, H.; Van Mansveld, R.; Paganelli, F.L.; Dekker, B.; Lammers, J.W.J.; Sahl, H.G.; et al. Synergistic activity of a short lipidated antimicrobial peptide (lipoAMP) and colistin or tobramycin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa from cystic fibrosis patients. Medchemcomm 2016, 7, 148–156.

- Zapotoczna, M.; Forde, É.; Hogan, S.; Humphreys, H.; O’Gara, J.P.; Fitzgerald-Hughes, D.; Devocelle, M.; O’Neill, E. Eradication of Staphylococcus aureus Biofilm Infections Using Synthetic Antimicrobial Peptides. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 215, 975–983.

- LL-37-Derived Membrane-active FK-13 Analogs Possessing Cell Selectivity, Anti-Biofilm Activity and synergy with Chloramphenicol and Anti-Inflammatory Activity-ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www-sciencedirect.ez87.periodicos.capes.gov.br/science/article/pii/S0005273617300457?via%3Dihub (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- LL-37-Derived Short Antimicrobial Peptide KR-12-a5 and its D-Amino acid Substituted Analogs with Cell Selectivity, Anti-Biofilm Activity, Synergistic Effect with Conventional Antibiotics, and Anti-Inflammatory Activity-ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www-sciencedirect.ez87.periodicos.capes.gov.br/science/article/pii/S0223523417303902?via%3Dihub (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Bormann, N.; Koliszak, A.; Kasper, S.; Schoen, L.; Hilpert, K.; Volkmer, R.; Kikhney, J.; Wildemann, B. A short artificial antimicrobial peptide shows potential to prevent or treat bone infections. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1506.

- Wang, Y.; Fan, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Tu, H.; Ren, Q.; Wang, X.; Ding, L.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, L. De novo synthetic short antimicrobial peptides against cariogenic bacteria. Arch. Oral Biol. 2017, 80, 41–50.

- Chang, T.-W.; Wei, S.-Y.; Wang, S.-H.; Wei, H.-M.; Wang, Y.-J.; Wang, C.-F.; Chen, C.; Liao, Y.-D. Hydrophobic residues are critical for the helix-forming, hemolytic and bactericidal activities of amphipathic antimicrobial peptide TP4. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186442.

- Olivo, E.A.C.; Santos, D.; de Lima, M.E.; dos Santos, V.L.; Sinisterra, R.D.; Cortés, M.E. Antibacterial Effect of Synthetic Peptide LyeTxI and LyeTxI/β-Cyclodextrin Association Compound Against Planktonic and Multispecies Biofilms of Periodontal Pathogens. J. Periodontol. 2017, 88, e88–e96.

- Loffredo, M.R.; Ghosh, A.; Harmouche, N.; Casciaro, B.; Luca, V.; Bortolotti, A.; Cappiello, F.; Stella, L.; Bhunia, A.; Bechinger, B.; et al. Membrane perturbing activities and structural properties of the frog-skin derived peptide Esculentin-1a(1-21)NH2 and its Diastereomer Esc(1-21)-1c: Correlation with their antipseudomonal and cytotoxic activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Biomembr. 2017, 1859, 2327–2339.

- Khara, J.S.; Obuobi, S.; Wang, Y.; Hamilton, M.S.; Robertson, B.D.; Newton, S.M.; Yang, Y.Y.; Langford, P.R.; Ee, P.L.R. Disruption of drug-resistant biofilms using de novo designed short α-helical antimicrobial peptides with idealized facial amphiphilicity. Acta Biomater. 2017, 57, 103–114.

- Lin, Q.; Deslouches, B.; Montelaro, R.C.; Di, Y.P. Prevention of ESKAPE pathogen biofilm formation by antimicrobial peptides WLBU2 and LL37. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2018, 52, 667–672.

- Deslouches, B.; Gonzalez, I.A.; DeAlmeida, D.; Islam, K.; Steele, C.; Montelaro, R.C.; Mietzner, T.A. De novo-derived cationic antimicrobial peptide activity in a murine model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteraemia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007, 60, 669–672.

- Haisma, E.M.; De Breij, A.; Chan, H.; Van Dissel, J.T.; Drijfhout, J.W.; Hiemstra, P.S.; El Ghalbzouri, A.; Nibbering, P.H. LL-37-derived peptides eradicate multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from thermally wounded human skin equivalents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 4411–4419.

- De Breij, A.; Riool, M.; Cordfunke, R.A.; Malanovic, N.; De Boer, L.; Koning, R.I.; Ravensbergen, E.; Franken, M.; Van Der Heijde, T.; Boekema, B.K.; et al. The antimicrobial peptide SAAP-148 combats drug-resistant bacteria and biofilms. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018, 10.

- Spencer, J.J.; Pitts, R.E.; Pearson, R.A.; King, L.B. The effects of antimicrobial peptides WAM-1 and LL-37 on multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Pathog. Dis. 2018, 76, 7.

- Almaaytah, A.; Qaoud, M.T.; Abualhaijaa, A.; Al-Balas, Q.; Alzoubi, K.H. Hybridization and antibiotic synergism as a tool for reducing the cytotoxicity of antimicrobial peptides. Infect. Drug Resist. 2018, 11, 835–847.

- Mohanraj, G.; Mao, C.; Armine, A.; Kasher, R.; Arnusch, C.J. Ink-Jet Printing-Assisted Modification on Polyethersulfone Membranes Using a UV-Reactive Antimicrobial Peptide for Fouling-Resistant Surfaces. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 8752–8759.

- Kang, H.K.; Seo, C.H.; Luchian, T.; Park, Y. Pse-T2, an antimicrobial peptide with high-level, broad-spectrum antimicrobial potency and skin biocompatibility against multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e01493-18.

- Kim, M.K.; Kang, N.H.; Ko, S.J.; Park, J.; Park, E.; Shin, D.W.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, S.A.; Lee, J.I.; Lee, S.H.; et al. Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Activity and Mode of Action of Magainin 2 against Drug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3041.

- Cardoso, M.H.; de Almeida, K.C.; Cândido, E.S.; Fernandes, G.d.R.; Dias, S.C.; de Alencar, S.A.; Franco, O.L. Comparative transcriptome analyses of magainin I-susceptible and -resistant Escherichia coli strains. Microbiology 2018, 164, 1383–1393.

- Omardien, S.; Drijfhout, J.W.; Zaat, S.A.; Brul, S. Cationic Amphipathic Antimicrobial Peptides Perturb the Inner Membrane of Germinated Spores Thus Inhibiting Their Outgrowth. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2277.

- Omardien, S.; Drijfhout, J.W.; van Veen, H.; Schachtschabel, S.; Riool, M.; Hamoen, L.W.; Brul, S.; Zaat, S.A.J. Synthetic antimicrobial peptides delocalize membrane bound proteins thereby inducing a cell envelope stress response. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Biomembr. 2018, 1860, 2416–2427.

- Kaletta, C.; Entian, K.D. Nisin, a peptide antibiotic: Cloning and sequencing of the nisA gene and posttranslational processing of its peptide product. J. Bacteriol. 1989, 171, 1597–1601.