Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 3 by Dean Liu and Version 2 by Dean Liu.

The mental health and well-being of graduate students are of increasing concern worldwide, and though it started as an implicit recognition that students suffer poor mental health, it has expanded into an area of publicly argued concern.

- bibliometrics

- graduate students

- knowledge structure

- mental health

1. Introduction

A broad transnational survey of over 14,000 students in eight countries, including Australia, Belgium, Germany, Mexico, Northern Ireland, South Africa, Spain, and the U.S., showed that 35% of students fulfilled the criteria for one or more identified mental health conditions. It was also identified that students requiring the greatest need in terms of major distress or, in particular, poor mental health are less likely to receive support or assistance [2][1].

In the U.S., it has been earlier reported that there is a catastrophe of mental health amongst students across institutions of higher learning [3][2]. The American Psychiatric Association established a mission panel on “College Mental Health” in 2005 to provide counsel and promote investigation and intervention programs. However, this remains a problem in the U.S., while related issues concerning student mental health were also reported in Canada, Australia [4][3], Turkey [5][4], and several other nations [6][5].

The U.K. Royal College of Psychiatrists [7][6] projected, in 2011, that the degree of mental health complications among students will upsurge based on factors including the government moving many students from a broader part of the community to school at higher institutions, with increasing financial pressures on students associated with declines in public funding to sustain the students while studying. Both academic scholars and the public have shown rising apprehension regarding the well-being of graduate students, stemming from anxiety, family issues, and the extent of expectations [8][7]. Attention to the graduate students’ journey is critical.

Graduate students are defined as individuals studying or conducting research at a higher level than a bachelor’s degree, focusing on doctorate and postdoctoral students. Doctoral students are those pursuing advanced studies beyond the master’s level to pursue an independent career, whereas post-doctoral trainees are beyond the doctoral level receiving training to pursue an independent career. These graduates are known as trainees because they receive extensive training and specialized instructions in preparation for a future in academia.

Graduate students experience a tremendous deal of stress due to high requirements, pressure, and the evaluative and competitive nature of the graduate school, which may contribute to increased stress and vulnerability [9][8]. In addition to their studies, graduate students often juggle other responsibilities, including supervision, teaching, or research assistance. Thus, academic and coursework difficulties, financial pressures, anxiety, and a lack of work–life balance are all stressors caused by the combined effort of these positions, leading to burnout, fatigue, depression, and physical health difficulties [10][9].

Studies support that graduate students face significant stress, and attention to their needs and challenges is paramount [11,12,13,14,15][10][11][12][13][14]. According to a survey, graduate students reported that their mental health had worsened during their education [16][15], while another reported that one out of every three students sought counseling for anxiety or depression over their journey through graduate school [17][16]. Supporting these views, Jones-White et al. [18][17] revealed factors contributing to graduate students’ anxiety and depressive disorders as a lack of a sense of belonging and academic, financial, and relationship stressors. One out of every three graduate students is at risk of having a mental health problem, such as depression [15][14]. Graduate students have a self-reported incidence of depression and anxiety six times higher than the general population and their peers in the same age bracket [14][13]. Therefore, they require more significant support to handle mental health concerns [19,20][18][19].

Numerous factors detrimental to students’ well-being are debatably exclusive to the postgraduate journey. Doctoral degree students struggle with emotions of social seclusion, absence of enthusiasm, difficulties with their advisors or supervisors, and loss of engagement with the educational community [12,21][11][20]. About 56% of doctoral students consider dropping out during the process due to experiences of anxiety, stress, exhaustion, and lack of interest [12][11]. Lately, consideration of such factors in studies has been reduced, as research has concentrated on how those elements influence their completion rate [22][21]. Considering the high degree of well-being hypothetically needed to accomplish a doctoral degree, it is no wonder that low well-being significantly impacts the students’ research progress, career advancement, academic efficiency, and private lives [22][21]. These problems have organizational and financial repercussions for higher educational institutions [12,23][11][22]. While existing studies have assessed some phases of mental health, most frequently, the aspects of psychological distress [12,15,16][11][14][15] and other aspects such as psychological well-being have not been well-researched.

Conventionally, mental well-being and mental distress were regarded to represent opposites of a particular dimension, with increasing mental well-being implying lower mental suffering and vice versa. Increased mental well-being has also been reported to reduce mental distress over a period, while declines in mental well-being reflect increased mental distress [24][23]. A variety of additional models for how mental well-being and mental distress interact to influence an individual’s mental health suggested that both mental well-being and mental distress have a role in graduate students’ overall mental health.

Therefore, there is a need to undertake continuous research on this topic to ensure that the related concerns are clearly and consistently mapped and intellectualized using appropriate and reliable tools for measurement. Seeing the high level of depression and anxiety among the doctoral student population, it is important to expand on research focused on this critical group given their job prospects and contribution to the broader society [25][24]. Doctoral students and postdoctoral trainees have the prospect of research, development, and education at institutions and beyond, but they are in danger of losing their jobs. The increasingly bleak job environment for scientific researchers adds to the dissatisfaction produced by long hours and low compensation. Though a bit of stress can be tolerated, anxiety and depression can be devastating. In 2021, for example, a study of doctoral students at seven United States (U.S.) universities found that 15.8% of them had considered suicide within two weeks before taking the survey. According to the survey, just one-third of those who fulfilled the diagnosis received therapy, and students with psychological problems were also more alienated, had fewer colleagues to resort to for support, and were much more inclined to consider quitting school [26][25]. Therefore, systematically monitoring and championing research on their mental health is paramount, ultimately contributing to increased completion rates [16,27,28][15][26][27]. Not recognizing and responding to this problem could result in a considerable loss of resources and human potential.

Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has likely made these difficulties more severe, and graduate students may find it even more challenging to seek support [29][28]. Some students may be hesitant to acknowledge it, let alone manage it, because of enormous competition, exacerbating the situation. According to research by the World Health Organization (WHO) [30][29], the number of persons with mental health disorders is expected to rise, and graduate students are among the most vulnerable groups. Therefore, research on this topic is vital.

2. The Development Trajectory of Studies on Graduate Students’ Mental Health and Well-Being

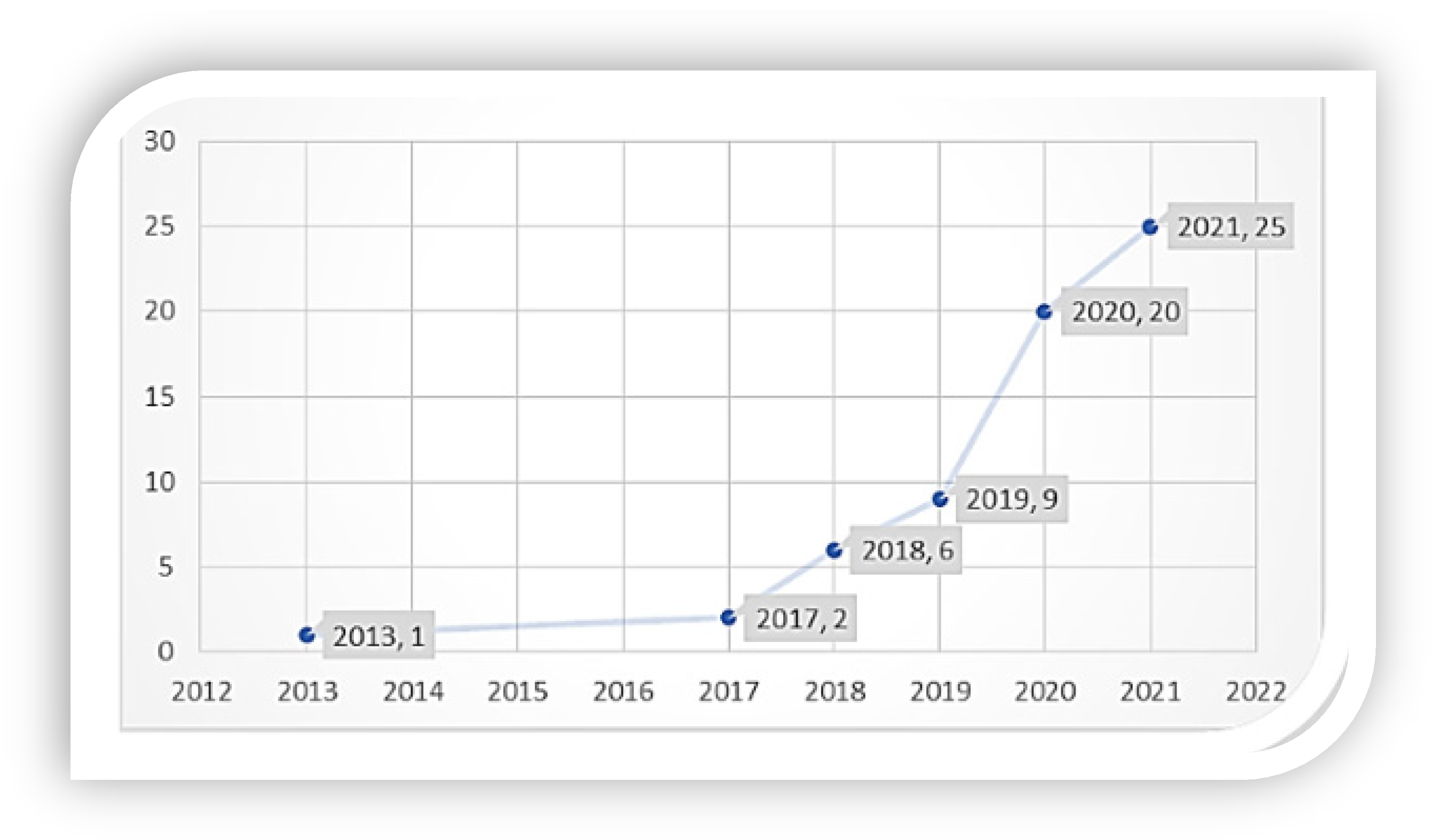

The numerical growth of research publications on a subject represents a vital indicator of the evolutional trend in that research domain. It mirrors the image of development and the advancement of knowledge on the subject. By analyzing of the number of published literature over the years, the state of research and the trend of imminent development in a particular field can be clearly interpreted and understood. In 2012–2021, research on graduate students’ mental health and well-being made up 63 publications on a global scale as indexed in Scopus. The number of published documents on the subject gradually increases over time, as shown in Figure 1. However, publications were relatively small in this area, numbering 18 from 2013 to 2019, suggesting that there has been limited attention to the predicament of this group of people through scholarly research. The growth trend witnessed publications significantly increase from 2020–2021. Specifically, the last two years have observed a remarkable growth of research in mental health in tertiary education, particularly among graduate students. These publications have heralded new opportunities and awareness in the educational sector leading to a scholarly community of research and publishing directed to reaching a wider audience. The publications also reflect that new researchers are increasingly examining the field instead of a set of researchers dominating a particular field. These findings suggest that the patterns may have been influenced by the incidence of the COVID-19 pandemic, which birthed plenteous research on mental health and the impact of the associated restrictions on research, teaching, and learning in higher education in general. The relevance of attention to students’ mental health was elevated given the sudden shift to remote or online learning, which possibly spiked research on graduate students’ well-being.

Figure 1. Publication Trajectory (year-wise).

3. Country-Wise Collaboration

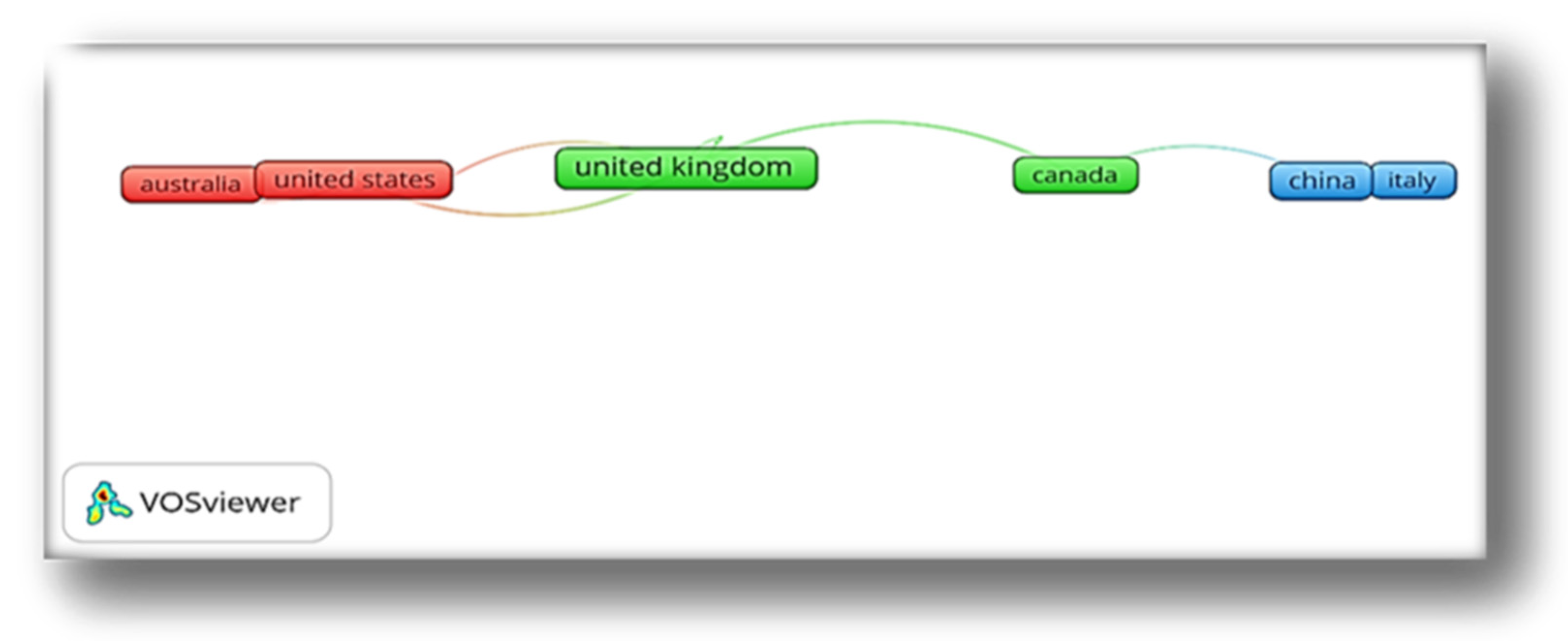

Figure 2 shows three clusters of countries that exhibit collaboration with other countries. The red cluster indicates collaboration between the U.S., New Zealand, Australia, and France. The green cluster has the highest collaboration, showing that the U.K. closely collaborates with the USA, Canada, France, and Spain, with a total link strength of 8. The collaboration in the blue cluster is China, Italy, and the Netherlands, with a link strength of 3, 2, and 2, respectively. The collaboration strength amongst the countries is generally weak and low, suggesting that most of the countries have primarily concentrated on independent and autonomous research regarding the mental health of graduate students and show limited cooperation with other researchers. Collaboration in mental healthcare has proven to produce positive outcomes for the affected [52][30]. This presents a strong case for the need for collaboration.

Figure 2. Country-level Collaboration Map of Countries.

References

- Gorczynski, P.; Sims-Schouten, W.; Hill, D.; Wilson, J.C. Examining mental health literacy, help-seeking behaviours and mental health outcomes in UK university students. J. Ment. Health Train. Educ. Pract. 2017, 12, 111–120.

- Kadison, R.; Digeronimo, T.F. College of the Overwhelmed: The Campus Mental Health Crisis and What to Do about It; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004.

- Stallman, H.M. Prevalence of psychological distress in university students--implications for service delivery. Aust. Fam. Physician 2008, 37, 673–677.

- Guney, S.; Kalafat, T.; Boysan, M. Dimensions of mental health: Life satisfaction, anxiety and depression: A preventive mental health study in Ankara University students population. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 2, 1210–1213.

- Karam, E.; Kypri, K.; Salamoun, M. Alcohol use among college students: An international perspective. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2007, 20, 213–221.

- Royal College of Psychiatrists, London. Mental Health of Students in Higher Education。 College Report CR166. 2011. Available online: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/better-mh-policy/college-reports/college-report-cr166.pdf?sfvrsn=d5fa2c24_2 (accessed on 9 October 2021).

- Hassel, S.; Ridout, N. An Investigation of First-Year Students’ and Lecturers’ Expectations of University Education. Front. Psychol. 2018, 8, 2218.

- Rummell, C.M. An exploratory study of psychology graduate student workload, health, and program satisfaction. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2015, 46, 391–399.

- El-Ghoroury, N.H.; Galper, D.I.; Sawaqdeh, A.; Bufka, L.F. Stress, coping, and barriers to wellness among psychology graduate students. Train. Educ. Prof. Psychol. 2012, 6, 122–134.

- Oswalt, S.B.; Riddock, C.C. What to do about being overwhelmed: Graduate students, stress and university services. Coll. Stud. Aff. J. 2007, 27, 24–44.

- Sverdlik, A.; Hall, N.C. Not just a phase: Exploring the role of program stage on well-being and motivation in doctoral students. J. Adult Contin. Educ. 2020, 26, 28–97.

- Hyun, J.K.; Quinn, B.C.; Madon, T.; Lusti, S. Graduate student mental health: Needs assessment and utilization of counseling services. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2006, 47, 47–266.

- Evans, T.M.; Bira, L.; Gastelum, J.B.; Weiss, L.T.; Vanderford, N.L. Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 282–284.

- Levecque, K.; Anseel, F.; De Beuckelaer, A.; Van der Heyden, J.; Gisle, L. Work organization and mental health problems in PhD students. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 868–879.

- Barreira, P.; Basilico, M.; Bolotnyy, V. Graduate Student Mental Health: Lessons from American Economics Departments. Working Paper. 2018. Available online: https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/bolotnyy/files/bbb_mentalhealth_paper.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Woolston, C. PhDs: The tortuous truth. Nature 2019, 575, 403–406.

- Jones-White, D.R.; Soria, K.M.; Tower, E.K.B.; Horner, O.G. Factors Associated with Anxiety and Depression among U.S. Doctoral Students: Evidence from the gradSERU Survey. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 1–12.

- Council of Graduate Schools & the Jed Foundation. Supporting Graduate Student Mental Health and Well-Being: Evidence-informed Recommendations for the Graduate Community. Executive Summary. CGS. 2021. Available online: https://cgsnet.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/CGS_JED_EXECUTIVE-SUMMARY-1.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Graduate STEM Education for the 21st Century; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Castelló, M.; Pardo, M.; Sala-Bubaré, A.; Suñe-Soler, N. Why do students consider dropping out of doctoral degrees? Institutional and personal factors. High. Educ. 2017, 74, 1053–1068.

- Anttila, H.; Lindblom, S.A.; Lonka, K.; Pyhältö, K. The Added Value of a PhD in Medicine—PhD Students’ Perceptions of Acquired Competences. Int. J. High. Educ. 2015, 4, 172–180.

- Schmidt, M.; Hansson, E. Doctoral students’ well-being: A literature review. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2018, 13, 1508171.

- Westerhof, G.J.; Keyes, C.L.M. Mental Illness and Mental Health: The Two Continua Model Across the Lifespan. J. Adult Dev. 2009, 17, 110–119.

- Kerdijk, W.; Tio, R.A.; Mulder, B.F.; Cohen-Schotanus, J. Cumulative assessment: Strategic choices to influence students’ study effort. BMC Med. Educ. 2013, 13, 172.

- Almasri, N.; Read, B.; Vandeweerdt, C. Mental Health and the PhD: Insights and Implications for Political Science. 2021. Available online: http://www.claravdw.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Almasri-Mental-Health-and-the-PhD.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Satinsky, E.N.; Kimura, T.; Kiang, M.V.; Abebe, R.; Cunningham, S.; Lee, H.; Lin, X.; Liu, C.H.; Rudan, I.; Sen, S.; et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation among Ph.D. students. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14370.

- Zhou, E.; Okahana., H. The Role of Department Supports on Doctoral Completion and Time-to-Degree. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. Res. Theory Pract. 2019, 20, 511–529.

- Czeisler, M.É.; Lane, R.I.; Petrosky, E.; Wiley, J.F.; Christensen, A.; Njai, R.; Weaver, M.D.; Robbins, R.; Facer-Childs, E.R.; Barger, L.K.; et al. Mental Health, Substance Use, and Suicidal Ideation During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 32, 1049–1057.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Mental Health: Facing the Challenges, Building Solution; WHO/Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2005; Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/96452/E87301.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education & Collaborative Practice. Practice. Geneva: Department of Human Resources for Health. 2010. Available online: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/cgi-bin/repository.pl?url=/hq/2010/WHO_HRH_HPN_10.3_eng.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Collins, P.Y.; Saxena, S. Action on mental health needs global cooperation. Nature 2016, 532, 25–27.

- Fernando, S. Race and Culture in Psychiatry; Routledge: Hove, UK, 2015.

- Sarafino, E.P. Health Psychology: Biopsychosocial Interactions, 6th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008.

- Fernando, S. Globalization of psychiatry—A barrier to mental health development. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2014, 26, 551–557.

- Tribe, R. The Mental Health Needs of Refugees and Asylum Seekers. Ment. Health Rev. J. 2005, 10, 8–15.

- FECCA. Mental Health and Australia’s Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Communities: A Submission to the Senate Standing Committee on Community Affairs; FECCA: Canberra, Australia, 2011.

- Gopalkrishnan, N. Cultural Diversity and Mental Health: Considerations for Policy and Practice. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 179.

- Amuyunzu-Nyamongo, M. The social and cultural aspects of mental health in African societies. Commonw. Health Partnersh. 2013, 2013, 59–63.

- Feldmann, C.T.; Bensing, J.M.; De Ruijter, A.; Boeije, H.R. Afghan refugees and their general practitioners in The Netherlands: To trust or not to trust? Sociol. Health Illn. 2007, 29, 515–553.

- Monteiro, N.M. Addressing mental illness in Africa: Global health challenges and local opportunities. Community Psychol. Glob. Perspect. 2015, 1, 78–95.

More