Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Vsevolod Yu. Prokofiev and Version 2 by Vivi Li.

The porphyry type of hydrothermal mineral deposits is of paramount economic importance because deposits of this type host much of the world’s reserves of Cu, Mo, and Re, as well as much Re and remarkable reserves of critical elements such as Ag, Pd, Te, Se, Bi, Zn, and Pb. Porphyry deposits are conventionally classified into mineralogical–geochemical types according to their dominant valuable components. The most economically important porphyry-type deposits are those of the Cu (Au), Cu–Mo (Au), Mo, and Au types.

- porphyry deposits

- copper

- molybdenum

- gold

- fluid inclusions

1. Introduction

The porphyry type of hydrothermal mineral deposits is of paramount economic importance because deposits of this type host much of the world’s reserves of Cu, Mo, and Re, as well as much Re and remarkable reserves of critical elements such as Ag, Pd, Te, Se, Bi, Zn, and Pb (e.g., [1][2][3][4][1,2,3,4]). Porphyry deposits are conventionally classified into mineralogical–geochemical types according to their dominant valuable components, e.g., [3]. The most economically important porphyry-type deposits are those of the Cu (Au), Cu–Mo (Au), Mo, and Au types.

Porphyry deposits have been studied for a long time, and their features have been much discussed in many reviews, e.g., [5]. Detailed reviews were published on the geology and geotectonic settings of porphyry deposits, zoning of the wall-rock metasomatites, and spatiotemporal relations between the ore mineralization and magmatism in porphyry systems, e.g., [3][4][6][7][8][9][3,4,6,7,8,9].

Porphyry deposits contain large reserves of ores with low Cu, Mo, and Au concentrations and are genetically linked to the emplacements and crystallization of melts ranging from diorite to granite in composition. Magma bodies that generate porphyry mineralization are usually constrained to plate margins, e.g., [1][2][3][4][7][8][1,2,3,4,7,8]. Porphyry deposits are usually zonal [10] and are stockworks of disseminated and stringer accumulations of sulfides and oxides hosted in large (up to 10 km3) volumes of hydrothermally altered rocks, which were produced by the large-scale circulation of hydrothermal fluids at upper crustal levels [2][3][4][11][12][13][14][2,3,4,11,12,13,14]. Porphyry deposits were found in continental magmatic belts worldwide, showing evidence of spatiotemporal and genetic relations to hypabyssal porphyritic diorite and granodiorite intrusions, which were produced by water-rich magmas.

According to the orthomagmatic model [4][10][15][16][4,10,15,16], porphyry copper mineralized magmas are usually emplaced into upper crustal levels (at depths of approximately 5–10 km). The gradually cooling melts approach their saturation with volatile components [17][18][17,18]. As soon as the melt reaches its saturation with volatiles, a phase of aqueous magmatic fluid (whose salinity is not high) is separated from the melt [17][18][17,18], and some elements (including sulfur, chlorine, copper, and some other metals) are, therewith, transferred from the melt into the aqueous phase to form mineralized aqueous magmatic fluid [3][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][3,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. Magmatic fluid ascends along fractures and cracks into the already-solid parts of the intrusions, alters host rocks, and comes, due to the pressure decrease, to the field of two-phase equilibrium, in which pressure is lower than 1300 bar (i.e., the region of ore deposition). In this region, the fluid exsolves (heterogenizes) into two phases: chloride brine and a low-density aqueous fluid [32][33][32,33]. The heterogenization of the fluid triggers the onset of ore deposition. The fluids then continue cooling, interacting with rocks and diluted meteoric waters, and depositing ore and gangue minerals [4][12][14][16][4,12,14,16]. Relics of the mineralizing fluids are captured as fluid inclusions, which can provide a record of the evolution of the parameters and composition of the fluids with time [34]. Many researchers have demonstrated that parameters of mineral-hosted fluid inclusions in porphyry hydrothermal systems systematically vary in space and with time, e.g., [26][31][34][35][36][37][38][39][26,31,34,35,36,37,38,39]. A model developed for H2O–NaCl fluid is able to realistically describe the distributions of various types of fluid inclusions (halite-bearing brine inclusions, gas inclusions, and liquid-rich two-phase inclusions) over the volumes of porphyry copper deposits [40]. Assemblages of brine and gas fluid inclusions mark domains with high-grade ores. It is important to specify that the fluid inclusion assemblage (FIA) is usually defined as the most finely discriminated group of cogenetic fluid inclusions occupying an individual petrographic feature (e.g., crystal growth-zone or healed fracture), as is unambiguously recognizable by microscopic methods. This model is able to predict the composition and parameters of fluid inclusions captured by minerals when porphyry fluid–magma systems spatiotemporally develop, which enables one to utilize these data for various practical purposes. Although porphyry deposits were studied in much detail, it is still interesting to correlate current understandings of their genesis with the available data on mineral-hosted fluid inclusions in porphyry Cu–Mo–Au systems.

It is pertinent to mention the following reviews of fluid inclusions in the minerals of porphyry systems, e.g., [5][26][34][38][41][42][43][44][45][5,26,34,38,41,42,43,44,45]. Some reviews were devoted to the parameters and composition of fluid inclusions in minerals from porphyry deposits, e.g., [31][46][47][31,46,47]. Fluid inclusions hosted in minerals at porphyry deposits are still actively studied, and extensive newly acquired data were published after the aforementioned reviews. Differences between the physicochemical parameters of fluids that produced all of the four types of porphyry deposits in the Cu–Mo–Au system still have not been adequately analyzed in the literature, likely because of the very broad variations in the homogenization temperature and salinity of the fluid inclusions.

2. Characterization of Fluids at Porphyry Deposits

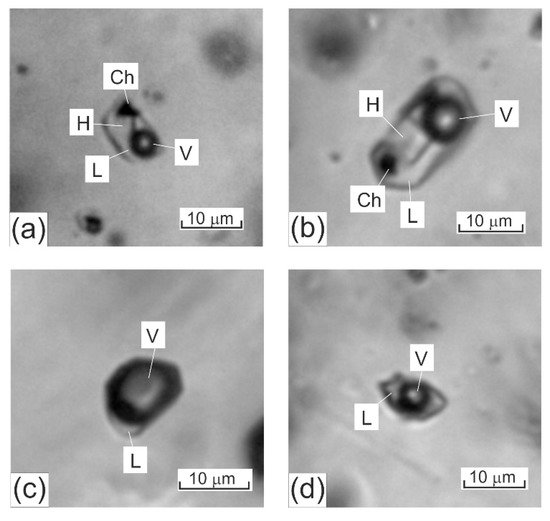

When fluid inclusions are characterized, their descriptions are, conventionally, begun with descriptions of how these inclusions look like at room temperature. Fluid inclusions hosted in minerals from porphyry deposits can be grouped into the following three types, according to the phase composition of these inclusions at room temperature (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Three major types of fluid inclusions typically hosted in quartz from mineralized veinlets at porphyry deposits: (a,b) fluid inclusions of high-temperature chloride brines (the photos show dark gas bubbles, transparent cubic NaCl crystals, opaque chalcopyrite crystals, and solution); (c) gas fluid inclusions (the photos show a gas phase and a pale rim of aqueous solution; (d) two-phase gas–liquid inclusions of aqueous solutions of intermediate salinity (the photos show a roundish gas phase and pale aqueous salt solution). The scale bars are 10 µm. L–aqueous solution, V–gas phase, H–halite, Ch–chalcopyrite.

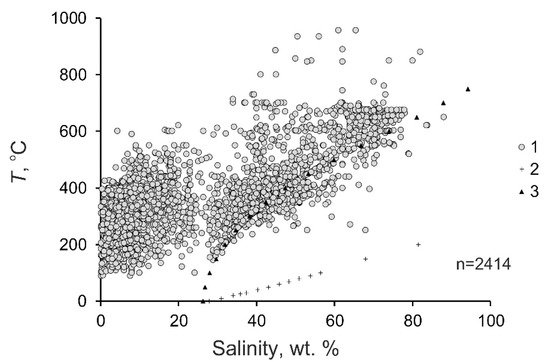

Figure 23. Diagram temperature–salinity for mineralizing fluids at porphyry deposits. 1—fluids at the deposits; 2—saturated KCl solution; 3—saturated NaCl solution.

Table 1. Parameters of mineralizing fluids at porphyry deposits.

| Deposit, Country, or Area | Physical Parameters of Fluid | Type ** of Deposit |

References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T, °C | S *, wt % | d, g/cm3 | Р, bar | |||

| Bingham Canyon, USA | ||||||

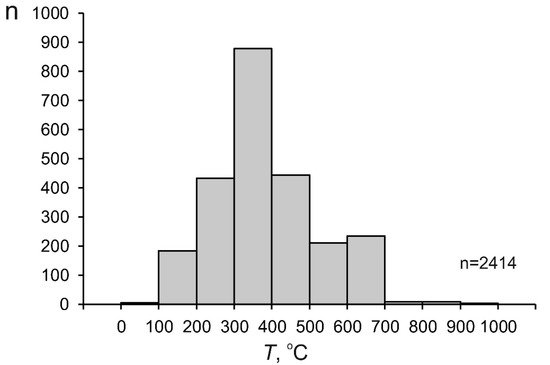

Figure 34.

Histogram of the temperature of mineralizing fluids at porphyry deposits.

Table 23.

Parameters of mineralizing fluids at porphyry deposits of different types.

| Types * of Deposits |

n | Temperature, °C | Salinity, wt. % | Density of Fluid, g/cm3 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interval | Average Arithmetic | Average Geometric | Interval | Average Arithmetic | Average Geometric |

Interval | Average Arithmetic | Average Geometric |

||||

| 405 (1) | 49.0 | 1.25 | - | 2 | [50] | |||||||

| All | 2414 | 90–957 | 388 | 372 | 0.1-88.0 | 29.4 | 28.2 | 0.38–1.85 | 0.93 | |||

| Butte, USA | 275–335 (2) | 1.0 | 0.62–0.76 | - | 2 | [50] | ||||||

| Climax, USA | 566 (1) | 69.0 | 1.45 | - | 3 | [50] | ||||||

| Copper Canyon, USA | 250–345 (3) | 1.2–40.0 | 0.80–1.06 | - | 1 | [53] | ||||||

| Kalmakyr, Uzbekistan | 375–800 (7) | 33.8–69.0 | 0.94–1.20 | 1000–1500 (4) | 2 | [54] | ||||||

| Bingham Canyon, USA | 350–616 (17) | 42.0–53.0 | 0.95–1.21 | - | 2 | [55] | ||||||

| Coloula, Papua New Guinea | 400–700 (4) | 34.0–62.0 | 0.60–1.30 | 1200 (1) | 1 | [56] | ||||||

| Inguaran district, Mexico | 226–360 (17) | 11.9–36.0 | 0.78–1.07 | - | 1 | [57] | ||||||

| Red Mountain, USA | 448–576 (6) | 52.0–68.0 | 1.12–1.50 | - | 1 | [58] | ||||||

| Washington, Mexico | 364–550 (2) | 34.5 | 0.81–0.98 | - | 2 | [59] | ||||||

| Mines Gaspe, Canada | 138-506 (68) | 9.5–56.0 | 0.60–1.25 | - | 1 | [60] | ||||||

| Santa Rita, USA | 775 (1) | 70.0 | 1.50 | - | 2 | [61] | ||||||

| Cumobabi, Mexico | 235–480 (8) | 2.9–50.0 | 0.63–1.12 | - | 2 | [62] | ||||||

| Questa, USA | 150–500 (16) | 2.0–57.0 | - | 800–1400 (8) | 3 | [25] | ||||||

| Sungun, Iran | 215–605 (54) | 2.2–59.8 | 0.54–1.12 | - | 1 | [63] | ||||||

| Far Southeast, Philippines | 450–550 (2) | 48.5–55.0 | 1.07–1.25 | - | 4 | [64] | ||||||

| Shotgun, USA | 270–509 (8) | 28.0–69.0 | 0.76–1.50 | - | 2 | [65] | ||||||

| Bajo de la Alumbrera, Argentina | 745–845 (2) | 62.0 | - | - | 1 | [66] | ||||||

| Escondida, Chile | 270–680 (10) | 3.0–67.0 | 0.68–1.23 | - | 1 | [67] | ||||||

| Bajo de la Alumbrera, Argentina | 615–845 (3) | 45.0–53.0 | - | - | 1 | [68] | ||||||

| Rosario, Chile | 237–593 (31) | 0.7–73.0 | 0.58–1.65 | - | 2 | [69] | ||||||

| Cerro Colorado, Chile | 90–544 (32) | 0.1–52.0 | 0.60–1.30 | - | 2 | [70] | ||||||

| El Teniente Deposit, Chile | 262–515 (49) | 2.1–60.5 | 0.47–1.15 | - | 2 | [71] | ||||||

| Bugdainskoe, Russia | 205–576 (11) | 6.9–70.5 | 0.66–1.45 | - | 2 | [72] | ||||||

| Fenghuangshan, China | 122–620 (100) | 3.4–71.5 | 0.63–1.40 | 1 | [73] | |||||||

| Talatui, Russia | 133–611 (50) | 0.4–56.3 | 0.47–1.21 | 108–3366 (37) | [82] | |||||||

| 0.95 | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 1017 | 91–957 | 437 | 421 | 0.2-88.0 | 39.4 | 41.4 | 0.40–1.85 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 2 | 923 | 90–800 | 359 | 363 | 0.1-73.0 | 26.3 | 28.6 | 0.41–1.65 | 0.91 | 0.96 | ||

| 3 | 193 | 129–566 | 349 | 354 | 0.7-69.0 | 13.8 | 8.5 | 0.43–1.45 | 0.85 | 0.83 | ||

| 4 | 280 | 4 | [ | 74 | ] | |||||||

| Butte, USA | 140–413 (14) | 1.0–48.0 | 0.41–1.14 | - | 2 | [51] | ||||||

| Questa, USA | 271–429 (21) | 2/8–50/0 | 0/43–1/12 | - | 3 | [52] | ||||||

| La Caridad Antigua, Mexico | 330–470 (13) | 28.0–56.0 | 0.95–1.15 | - | 1 | [75] | ||||||

| 100–611 | Nevados de Famatina, Argentina | 175–552 (22) | 1.5–64.4 | 0.46–1.48 | - | 2 | [76] | |||||

| Xiongcun, China | 121–382 (37) | 1.9–34.6 | 0.59–1.16 | - | 1 | [77] | ||||||

| Qiyugou, China | 157–460 (24) | 3.7–37.2 | 0.58–1.02 | - | 4 | [78] | ||||||

| Bingham Canyon, USA | 323–492 (3) | 34.7–50.4 | 0.90–1.10 | - | 2 | [79] | ||||||

| Baogutu, China | 151–550 (90) | 0.2–66.8 | 0.46–1.22 | 307–3128 (9) | 2 | [80] | ||||||

| Qiyugou, China | 109–476 (21) | 3.9–47.0 | 0.65–1.10 | - | 4 | [81] | ||||||

| Xishizishan, China | 131–570 (7) | Shizishan, China | 148–600 (11) | 2.1–56.2 | 0.52–1.10 | 1 | [82] | |||||

| 329 | 341 | 0.2-61.9 | 13.0 | 9.0 | 0.38–1.25 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 1.1–54.5 | 0.87–1.12 | - | 1 | [82] |

| Huashupo, China | 191–525 (10) | 9.6–49.9 | 0.70–1.01 | - | 1 | [82] | ||||||

| Datuanshan, China | 205–437 (7) | 7.6–43.8 | 0.72–1.09 | - | 1 | [82] | ||||||

| Tongguanshan, China | 289–885 (12) | 6.0–44.9 | 0.64–1.16 | - | 1 | Shizishan, China | 158–610 (13) | 2.1–56.2 | 0.56–1.19 | - | 1 | [83] |

| Shaxi, China | 110–520 (10) | 8.0–58.0 | 0.71–1.13 | - | 1 | [83] | ||||||

| Tongniujing, China | 192–450 (3) | 30.0–48.0 | 1.00–1.11 | - | 1 | [83] | ||||||

| Xiaomiaoshan, China | 91–369 (4) | 0.7–43.0 | 0.81–1.14 | - | 1 | [83] | ||||||

| Baocun, China | 240–310 (4) | 16.1–26.0 | 0.91–1.01 | - | 1 | [84] | ||||||

| Datuanshan, China | 160–440 (12) | 8.7–29.3 | 0.67–1.03 | - | 1 | [84] | ||||||

| Dongguashan, China | 170–450 (7) | 17.0–53.3 | 0.93–1.12 | - | 1 | [84] | ||||||

| Chaoshan, China | 220–280 (2) | 17.0 | 0.91–0.98 | - | 1 | [84] | ||||||

| Duobuza, China | 616–957 (33) | 34.0–74.0 | 0.75–1.80 | 400–1600 (15) | 1 | [85] | ||||||

| Mount Leyshon, Australia | 150–595 (64) | 0.2–61.9 | 0.38–1.13 | - | 4 | [86] | ||||||

| Bingham Canyon, USA | 313–610 (121) | 3.3–59.0 | 0.42–1.21 | - | 2 | [87] | ||||||

| Novoe Manto, Russia | 100–365 (9) | 9.6–24.2 | 0.86–1.15 | - | 1 | [88] | ||||||

| Jinchang, China | 200–620 (42) | 0.4–74.0 | 0.40–1.55 | - | 1 | [89] | ||||||

| Maher-Abad, Iran | 150–488 (20) | 9.5–47.9 | 0.80–1.13 | - | 1 | [90] | ||||||

| Peschanka, Russia | 205–506 (10) | 0.2–55.0 | 0.4–1.11 | - | 1 | [91] | ||||||

| Kighal, Iran | 180–600 (6) | 23.0–70.0 | 0.79–1.50 | 2 | [92] | |||||||

| Malysh, Russia | 129–545 (26) | 0.7–47.0 | 0.55–1.09 | 270–470 (2) | 3 | [93] | ||||||

| Peschanka, Russia | 104–506 (40) | 0.2–55.7 | 0.43–1.36 | 220–540 (8) | 1 | [93] | ||||||

| Nakhodka, Russia | 122–581 (10) | 2.1–57.8 | 0.51–1.14 | 280–850 (3) | 1 | [93] | ||||||

| Dexing, China | 105–524 (33) | 1.1–63.0 | 0.58–1.19 | 1500–3000 (2) | 2 | [94] | ||||||

| Vasil’kovskoe, Kazakhstan | 100–550 (126) | 2.0–22.5 | 0.47–1.03 | 150–2300 (69) | 4 | [95] | ||||||

| Malmyzh, Russia | 331–850 (9) | 27.0–80.0 | 0.95–1.13 | - | 1 | [96] | ||||||

| Pebble, USA | 147–535 (157) | 0.1–61.0 | 0.41–1.20 | - | 2 | [97] | ||||||

| Qarachilar, Iran | 190–530 (15) | 9.2–55.0 | 0.65–1.12 | - | 2 | [98] | ||||||

| Machangqing, China | 202–550 (15) | 12.7–22.1 | 0.51–1.09 | - | 2 | [99] | ||||||

| Yulong, China | 220–600 (20) | 2.0–46.0 | 0.48–1.07 | - | 2 | [99] | ||||||

| Tongchang, China | 240–460 (15) | 2.0–52.0 | 0.80–1.13 | - | 2 | [99] | ||||||

| Seleteguole, China | 268–483 (54) | 2.1–57.4 | 0.48–1.14 | - | 2 | [100] | ||||||

| Malmyzh, Russia | 260–525 (10) | 0.4–60.0 | 0.45–1.14 | 500 (2) | 1 | [101] | ||||||

| Grasberg, Indonesia | 255–700 (25) | 6.4–74.7 | 0.48–1.12 | - | 1 | [102] | ||||||

| № 1, China | 132–522 (104) | 0.9–62.8 | 0.41–1.19 | 1 | [103] | |||||||

| Kışladağ, Turkey | 250–600 (35) | 1.0–49.0 | 0.47–1.04 | - | 4 | [104] | ||||||

| Grasberg, Indonesia | 228–700 (403) | 1.4–88.0 | 0.625–1.47 | - | 1 | [105] | ||||||

| Sadaigoumen, China | 211–510 (122) | 1.2–50.6 | - | 10–600 (8) | 3 | [106] | ||||||

Note: * fluid salinity in wt % equiv. NaCl (numerals in parentheses show the number of determinations); ** types of porphyry deposits: 1–Cu (Au); 2–Cu, Mo (Au); 3–Mo; 4–Au.

Note: * types of porphyry deposits: 1–Cu (Au); 2–Cu, Mo (Au); 3–Mo; 4–Au; n: number of measurements.

It shall be mentioned that some papers report homogenization temperatures of fluid inclusions higher than 600 °C, with these values obtained using high-temperature heating stages. Such data usually provoke no doubts, if the publication reports information that these data are reproducible. However, rwesearchers rejected homogenization temperatures above 700 °C (up to 1290 °C) obtained for the Grasberg deposit [102][105][118,121], since the authors themselves were not sure whether these values do characterize the processes that produced the ores. Indeed, fluids at porphyry deposits contain much Fe and can lose protons because of water dissociation when heated to very high temperatures; the protons can migrate from the fluid inclusions through their host quartz and, thus, irreversibly change the composition of the fluid inclusions and result in overestimates of their homogenization temperatures, e.g., [34][107][108][34,126,127].

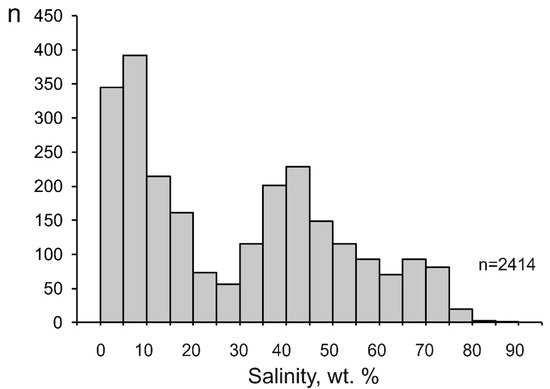

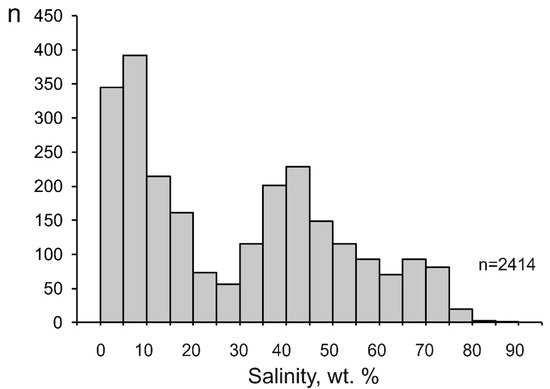

The salinity of the mineralizing fluids varies from 0.1 to 88.0 wt % equiv. NaCl (29.4 wt % equiv. NaCl on average). Some salinity values of fluids at porphyry deposits extend outside the H2O–NaCl saturation line, but they are no higher than the KCl solubility. (Figure 23). This is consistent with the sylvite that was found among the daughter minerals in fluid inclusions and with the occurrence of potassic metasomatites at porphyry deposits. The histogram of the salinity of the fluids has two maxima, at 0 to 10 and 35 to 45 wt % (Figure 45). This reflects the heterogenization of fluid, a process during which porphyry deposits start to be formed.

Figure 45.

Histogram of the salinity of mineralizing fluids at porphyry deposits.

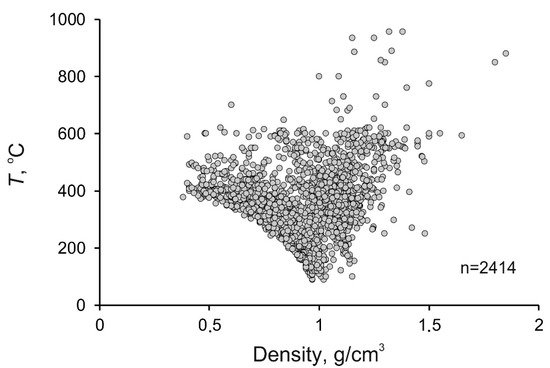

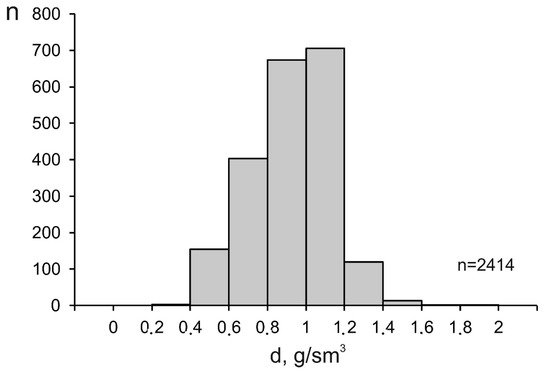

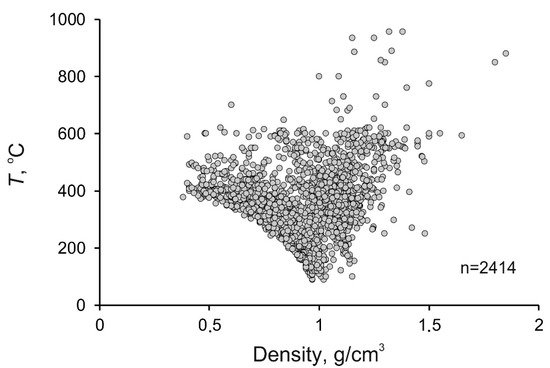

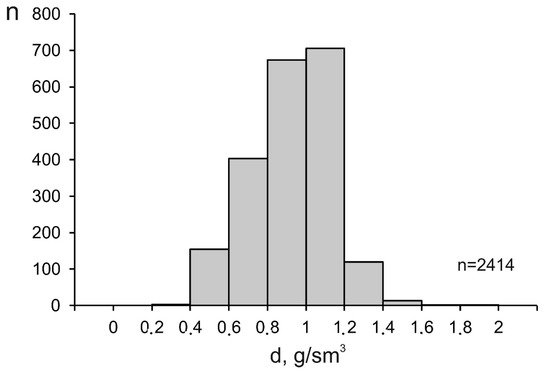

The density of mineralizing fluids at porphyry deposits also varies broadly, from 0.33 to 1.85 g/cm3 (average 0.93 g/cm3), since this parameter is interrelated with, first of all, the temperature and salinity of the fluids. The maximum variations in the fluid density were found at temperatures above 300 °C (Figure 56), which is also related to the heterogenization of the fluids. Below 200 °C, the density of the fluids approaches 1 g/cm3 because of the temperature decrease and the occurrence of the fluid in the homogeneous region. The histogram of the fluid density is unimodal, with its maximum occurring at 1.00 to 1.10 g/cm3 (Figure 67).

Figure 56.

Diagram temperature–density for mineralizing fluids at porphyry deposits.

Figure 67.

Histogram of the density of mineralizing fluids at porphyry deposits.

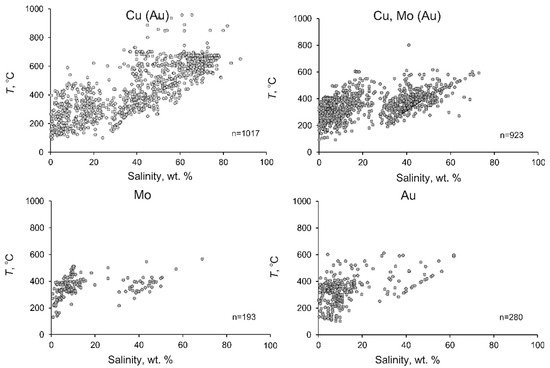

Some systematic differences were found between the average and maximum values of the parameters of the mineralizing fluids at porphyry deposits of various types (Table 23, Figure 78).

Figure 78.

Temperature–salinity diagram for mineralizing fluids at porphyry deposits of different types.

The average homogenization temperatures, salinity, and density of the fluids at deposits of various types commonly systematically decrease from deposits of type 1 to those of type 4. Figure 78 shows that the variations of the homogenization temperatures and salinity of the fluids at deposits of various types are generally similar, but the fields of these variations systematically shrink. This situation is not universal for the maximum homogenization temperatures. The minimum values of the maximum homogenization temperatures of fluids were found at porphyry Mo deposits (type 3), which may be explained by the fact that the numbers of measurements at deposits of types 3 and 4 are smaller.

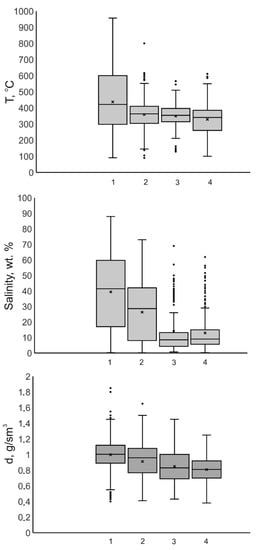

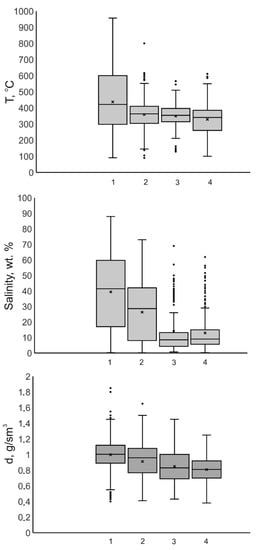

The great scatter of fluid parameters at each deposit (for example, the temperature ranges within a few hundred grades) inevitably puts forth the problem of the significance of the detected differences (for example, the average temperatures vary within as little as 10–40 °C) between the average parameters of fluids at porphyry deposits of different types. To sort out anomalous outlier values and be able to more accurately compare available data on various parameters, including those in the regions with 50% of the data (Figure 89), rwesearchers have constructed boxplots. The diagram for the temperatures (Figure 89), obviously, shows that porphyry copper deposits of type 1 are noted for the highest maximum and average homogenization temperatures of fluid inclusions. Porphyry copper–molybdenum deposits of type 2 show intermediate values of the average and maximum temperatures, and porphyry molybdenum deposits of type 3 and porphyry gold deposits of type 4 are relatively low temperature. The situation with the salinity diagrams is generally analogous for the maximum and average values of this parameter (Figure 89). The highest salinity is typical of fluids at porphyry copper deposits of type 1, intermediate salinity values were found in fluids at porphyry molybdenum deposits of type 2, and the lowest values were detected in fluids at molybdenum deposits of type 3 and porphyry gold deposits of type 4. It should be mentioned that fluids at porphyry molybdenum deposits of type 3 and porphyry gold ones of type 4 yield the narrowest ranges of the dominant salinity values of the fluids. The density values of the fluids do not vary as widely (Figure 89), but the average density of the fluids, obviously and systematically, decreases from type 1 (Cu(Au)) to type 4 (Au). This led researcherus to the conclusion that mineralizing fluids at porphyry deposits of different types are different in composition and have different parameters.

Figure 89. Boxplots for the homogenization temperatures of fluid inclusions, for the salinity of mineralizing fluids and for the density of mineralizing fluids at porphyry deposits of various types (1–Cu (Au); 2–Cu, Mo (Au); 3–Mo; 4–Au).

Here and in Figure 910, lines in the boxes are medians, crosses are averages, and spots are outliers (https://towardsdatascience.com/understanding-boxplots-5e2df7bcbd51, accessed on 11 September 2018).

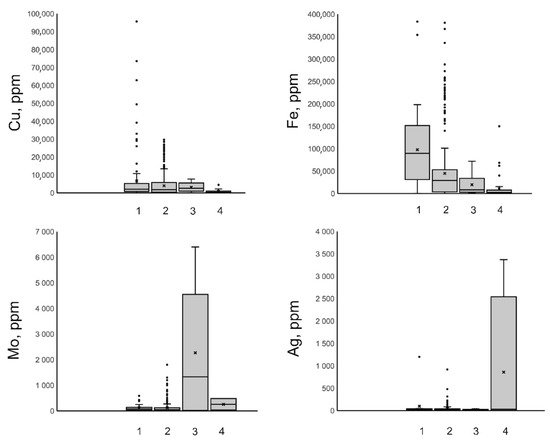

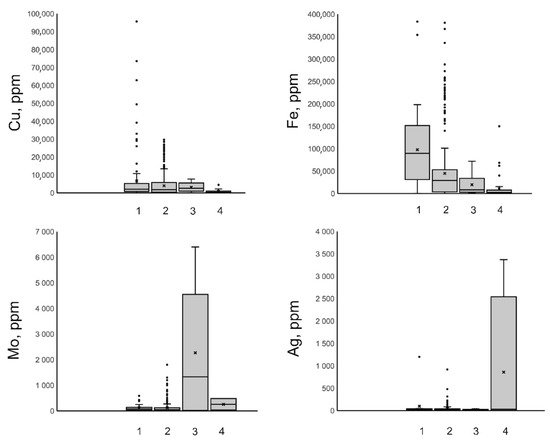

Figure 910. Boxplots for concentrations of Cu, Fe, Mo, and Ag, in mineralizing fluids at porphyry deposits of various types (1–Cu (Au); 2–Cu, Mo (Au); 3–Mo; 4–Au).